This Jail Is Accused of Favoring Christians Who Agree to Live in ‘God Pod’

Credit to Author: Kira Lerner| Date: Mon, 10 Dec 2018 13:50:45 +0000

A version of this story was originally published by The Appeal, a nonprofit criminal justice news outlet.

When Mitchell Young was detained in Virginia’s Riverside Regional Jail last spring, he asked officials at the facility to help him observe the Muslim holy month of Ramadan. Jails across the country make special accommodations for Muslim prisoners during this time by serving them meals before sunrise and after sunset, but his request was denied.

If Young had been Christian, a new complaint alleges, the jail would have made his life far easier.

Riverside Regional Jail explicitly favors Christian prisoners, asserts the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), a national Muslim civil rights group that on November 21 filed a federal complaint on behalf of Young and other Muslims in the jail.

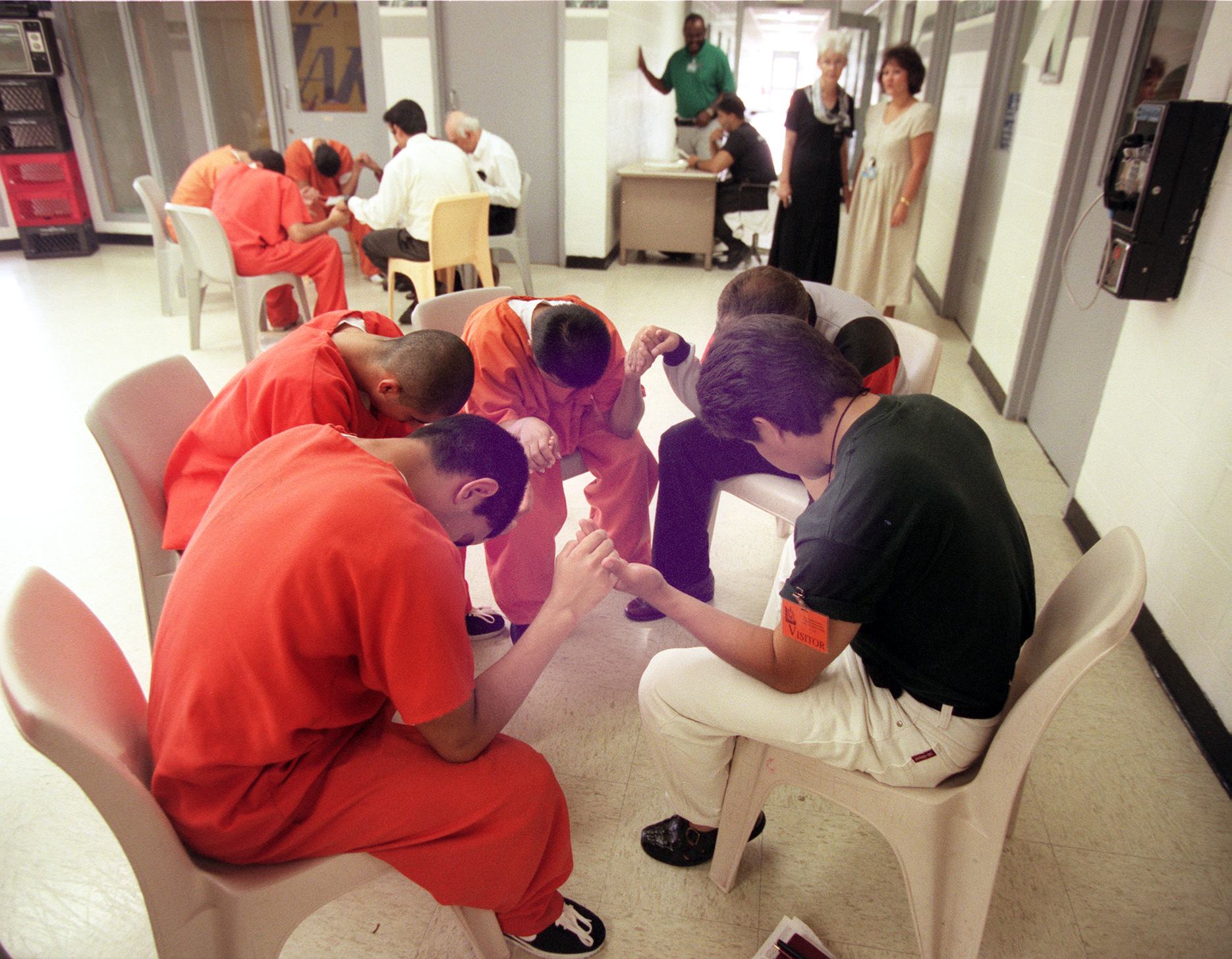

At the jail, which houses more than 1,300 people in Prince George, Virginia, individuals who agree to study and live in accordance with the Bible can live in a separate housing unit.

There are 30 to 40 prisoners living in the segregated area, known as the “God Pod.” They are locked down for significantly less time each day than the general population of the jail, the lawsuit alleges. They also are given such resources as writing materials and Bibles and are allowed time to study religious texts with others.

“It’s a systematic attempt to favor one religion over another,” Gadeir Abbas, an attorney with CAIR, told The Appeal. “It’s facility-wide. The God Pod is the crown jewel in that effort, but the suppression of Islamic education opportunities is a reflection of the facility’s really broad commitment to favoring one faith over another.”

Muslims in the jail allege that they face discrimination for their religious beliefs. Young and other prisoners say they were routinely starved during Ramadan and were denied access to religious materials, prevented from meeting with religious leaders, and prohibited from studying the Quran in groups.

Together, the morning and evening meals that the jail provides during Ramadan have far fewer calories than required, the lawsuit claims. In his original complaint, Young said that the jail also served him food at the wrong times of day, so he often went hungry or was forced to eat cold meals.

“On 5/25/18, I stated to Sgt. Jones as a Muslim my sunset tray (Maghrib) should be warm when served,” Young wrote. “Sgt. Jones stated to me ‘I don’t care if the tray is warm or cold. Get out of my face. If you have a problem file a grievance.”

Young claimed that other jail staff told him they “didn’t feel like” getting him meals at the appropriate times during Ramadan.

“I have been mentally, physically, and emotionally scarred and the damage is irreprehensible,” Young wrote in a pro se complaint filed in August, before CAIR took up the fight. “The residual effects of these acts can be felt daily in the social and religious climate around me.”

At the jail, only those who vow to live in accordance with the Bible are permitted to live in the God Pod, according to the complaint. “There’s no reason to religiously segregate inmates and it violates a really core principle of the First Amendment that government can’t favor or disfavor any faith,” Abbas said.

The God Pod is the brainchild of the jail’s senior chaplain, Joe Collins. Collins is an employee of the Good News Jail and Prison Ministry, a Virginia-based nonprofit dedicated to evangelizing to people in prison since 1961. The organization says it provides more than 376 staff chaplains in 115 institutions in 21 states and 25 foreign countries.

Good News has assumed a more significant role than most outside groups that send volunteers into prisons by having its staff members take on the official role of chaplains, which allows them to advise wardens on religious matters and set policy within facilities. Good News’ chaplains often end up creating inequities inside prisons by favoring individuals of one faith over others, Abbas said.

“They’re really clear about what their goals are: to bring the Bible to every inmate,” Abbas said. “Good News appears to take a really aggressive approach that involves them commandeering the authority of the facility to advance their religious mission, which is a clear Establishment Clause violation.”

Good News President Jon Evans told The Appeal that in US prisons and jails that have the resources, Good News pushes for segregated housing for those who chose to participate in the organization’s program. Participants are in class “a large percentage of the day,” Evans said, requiring that they live in a separate area. Between ten and 12 US jails and prisons currently provide separate housing for participants in Good News’ program, he said.

Individuals of any faith can live in the segregated pods, Evans said, so long as they agree to follow Good News’ curriculum and study the Bible.

Laura Gray, the public information officer for the jail, declined to comment on the litigation. Collins did not respond to request for comment.

In the Riverside Regional Jail, Collins has broad authority to control religious services and accommodations for all prisoners. While Collins has an official role in the jail, the facility has also denied access to religious leaders from other faiths who have offered to act as volunteer chaplains in the jail, according to the lawsuit.

“Those chaplains were consistently given a hard time and some of them have given up coming to the facility and providing classes because they were unable to get past the hurdles that the facility was placing on them,” Lena Masri, CAIR’s director of litigation, told The Appeal.

Evans denied allegations that Good News discriminates based on religion or that its chaplains prevent prisoners from practicing faiths other than Christianity. He claimed that jails and prisons set their own policies on whether to allow other religious leaders access to their facilities. Yet he also said that Good News provides all religious programming in the jails and prisons where they have chaplains.

“In most of the facilities in the United States, we facilitate all of the religious activities for all inmates, regardless of their religion,” Evans said.

CAIR has filed suit against other jails that use Good News’ services in ways that they say discriminate against Muslim prisoners, including one facility in Prince George’s County, Maryland where staff have held Muslim prisoners in solitary confinement for trying to pray in groups. Masri said Bible study groups are permitted in the jail. CAIR has also successfully sued corrections facilities in Alaska, Washington, and Michigan that were starving people during Ramadan, forcing the facilities to accommodate their Muslim prisoners.

Other legal actions have taken on the alleged preferential treatment of prisoners of certain religions.

A woman convicted of murder filed a suit last year against the Topeka Correctional Facility in Kansas, claiming that the prison pushes religious imagery, activities, and prayers on its population, amounting to state-sponsored religion.

In 2003, Americans United for Separation of Church and State sued an Iowa prison for giving preferential treatment to participants in a prison ministry. Individuals in the program were given access to more private cells, more contact with family members, and a faster track to parole. The challenge was successful, and a court ordered the prison to shut down the program.

Still, Abbas said the litigation against Riverside is unique because it is the first jail in which he had seen state officials allow prisoners of a certain faith to live in a separate space.

“There hasn’t really been litigation around this question of, ‘Can prisons religiously segregate inmates?’” Abbas said. “I think that reflects how unique of a situation this is. It’s not only a legal principle—it’s really an accepted norm that governments are not going to nakedly and openly prefer one faith over another.”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Kira Lerner on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.