The Bizarre Untold Origin Story of the Myers-Briggs Personality Indicator

If you’ve ever been on a dating app, you know what the Myers-Briggs personality type is—those four letters that are supposed to unlock the secrets of your inner personality and guide you through everything from your career to your interpersonal relationships. There’s (E) and (I) for extraversion or introversion, (N) and (S) for intuition or sensing, (T) and (F) for thinking or feeling, and (J) and (P) for judging or perceiving. This four-letter classification is hard to avoid. Some companies use it as a management tool, individuals use it to judge their Tinder dates, Redditors even obsess over it in subreddits dedicated to each type.

To classify yourself, you take the Myers-Briggs Personality Indicator (MBTI). (It is an “indicator” not a “test” because there are no wrong answers. Myers-Briggs advocates feel strongly about this.) Your type is as immutable as the star sign you were born under—the foundational fiber of your personality is inert and innate. You can even pay $175 to the Center for Applications of Psychological Type (CAPT) for a full “career breakdown.” This is, of course, pseudoscience. At this point, the MBTI has been pretty thoroughly debunked—it does not predict behaviour consistently, nor was it designed with any kind of scientific rigor. But that hasn’t stopped people from buying into it.

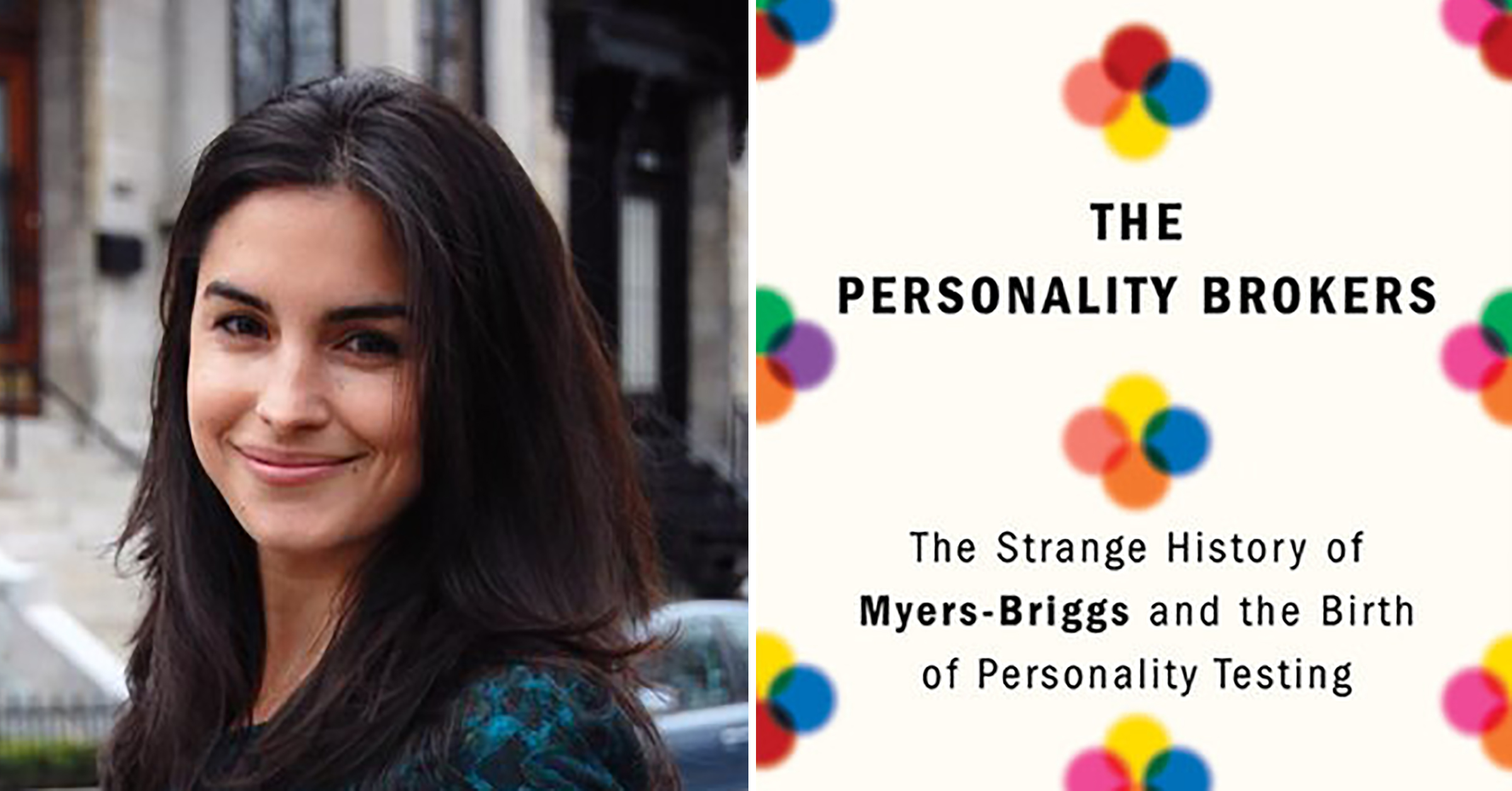

Merve Emre, an associate professor of English at Oxford, addresses this tension in her forthcoming book The Personality Brokers, which traces the lives of the two women who created the test—the mother-daughter pair of Katharine Cook Briggs and Isabel Briggs Myers. In recounting their lives, she examines how a methodology created from studying their husbands and children blossomed into one of the largest pseudoscientific personality testing models in history.

I spoke to Emre about the genesis of her book, and why the MBTI has had such enduring appeal:

VICE: Why were you interested in writing a book about the Myers-Briggs Personality Indicator?

Merve Emre: Right after college I worked as a consultant at Bain & Company. At my second week of associate consultant training, I had to take the MBTI at an offsite where we were debriefed about our personality types. Every time you’d get assigned a new team, the team leader would ask everyone what their type was and try to predict what the group dynamics would be based off of what everyone’s types were. So it’s like, “Oh, you an ‘E’ are directly reporting to an ‘I.’ These are the kinds of communication conflicts you might have.”

Many years later, I was thinking of writing a book about the relationships between personality and character. I became re-interested in the MBTI, and I started to do research. I discovered Isabel Briggs was a detective novelist and when I started reading her novels I became interested in her archives.

In the book, you describe having to take a $2,500 multiple-day course through CAPT for the opportunity to have access to Isabel’s archives. But they never let you in.

Right. No one had ever been allowed access to those archives—so it wasn’t as if I was the only person that was blocked from them. I became very curious about what might be in the archives, what they had to hide, what they didn’t want people poking around in, in the history of the indicator. And so that was when I decided the write the book about it.

Where did you turn when you realized CAPT would never open its archives?

When I didn’t get access to the archives I thought I just didn’t have a book to write. And I was frantically searching to see if [Isabel’s] mother had any archives. I kept searching under Katharine Briggs, because that was her married name, and it occurred to me one morning that I should be searching under her maiden name, Katharine Cook. Once I did that I discovered that there was an immense repository of her papers at Michigan State University. Boxes upon boxes of her diary entries, her correspondences with people—with [famed psychoanalyst Carl] Jung and her daughter and her husband. Just an incredible wealth of material there that I don’t think anybody knew about. I don’t think the people at CAPT knew about it.

The second half of the book moves from their home to these institutions of personality testing—and there were some really fascinating archives I got to dive into. One of the chapters of the book is called “The House Party Approach to Testing,” and it tells the story of how, in the late 50s, the psychologist named Donald MacKinnon bought a fraternity house in Berkeley, and he would have people come live in it for very long weekends and he would do personality assessments of them. At one point he got really interested in figuring out what made for a creative type of person. So he got all of these creative writers to come live at this house for a long weekend. These writers included Truman Capote, William Carlos Williams, Marianne Moore, and Norman Mailer—every major writer in Cold War America came to live in that house. And it was like a proto-Real World. They were living in this house where MacKinnon was putting them in situations of stress to see how they’d react to one another.

Did you find yourself using the language of type to navigate your own interpersonal relationships as you were writing this?

I started writing this when my older son was born and finished writing it when my younger son was born. I had a skepticism towards the idea that personality was innate, that people were simply born with these different types. But when I watch my children, even now, there are tremendous differences between them—and there have been since the days they were born—that can’t really be explained by anything institutional. Nothing in the structure of the family or, say, the school—or anything else—but that seem particular to each of them and somehow biologically determined.

I think once I realized that, then some of the skepticism I felt towards Katharine’s and Isabel’s ideas waned. I also became less skeptical of the idea that you could gain valuable knowledge from the act of caring for other people. I think one of the reasons it’s so easy to dismiss Katharine and Isabel’s work is because they did it in their homes. They drew the knowledge they had of personality by interacting with their children, and we don’t tend to think of that as something we ought to take seriously. In the book I wanted to ask, “What if we took that knowledge seriously? And what if we believed it could offer some kind of insight?”

One of the things I think that continues to make the MBTI so compelling and that Isabel consistently linked to her status as a mother is its non-judgmentalness. The idea that it will not force you to be the kind of person you don’t want to be, but that it will only help you perfect the kind of person you are.

This seems like such a large part of why people claim to have self-actualized through the Myers-Briggs—the thought that knowing yourself, and not judging yourself harshly, can lead to self-actualization. And it’s a lot cheaper than therapy.

I think those two things absolutely go hand in hand. That once you have the language—extraversion, intuition, sensing—in hand, all of a sudden you can design this life practice for yourself and how it is that you will best embrace those attributes. Where this gets thorny is what the purposes of self-actualization actually are. I can be liberating to know who you are and to believe you are now the master and arbiter of your own destiny, but it can also be used by institutions for more or less insidious means. It’s important to qualify that self-knowledge and self-actualization don’t lead to some kind of freedom.

For a while CAPT had this slogan that said something like, “You are not one in 16, you are one in a million.” It’s cheesy now—this was in the late 80s or early 90s—but what this slogan is trying to get at is that you can feel both a sense of belonging and a sense of deep individuality in the indicator, and that you feel like you can recognize yourself in others of your type, and that you share some kind of connection with them. At the same time you don’t have to be worried that who you are as a person will ever be completely absorbed by the type descriptor. I think that’s really the tension that continues to make the indicator so seductive.

And I’m willing to entertain the idea that the categories are measuring something. The interesting question to me is: Are they really measuring what we call “extraversion” or “introversion,” or are those just categories that are totally historically contingent? They’re useful categories for certain kinds of purposes and that’s why they’re used. But are they really innate? I don’t think so.

You write extensively about the MBTI’s capitalist applications. How do you think the MBTI fits into the doctrine of people as “personal brands”? Type indicators must have a specific potency when your corporate worth is simply your curated personality, right?

I think millennials are much savvier about the pitfalls of personality testing than, say, boomers. And one of the things I find utterly fascinating is the way BuzzFeed quizzes have taken the logic of personality testing and made it so parodic, so obvious. And they’ve done this in ways I’m not always sure they’re aware of.

My favorite quizzes are the ones where you click through a bunch of commodities—what Disney movie are you, what type of shoe are you—and then it uses all of those inputs to create another commodity as an output. Like, if you pick this kind of shoe, you’re this kind of Taylor Swift song. To me that’s a really amusing amusing exposé of how type works and has always worked. It’s used to commodify people’s psyches to transform them into commodities that can then be sold on the personality marketplace. So I actually think millennials are much more keyed into how that has become an invisible feature of their lives than any other generation.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Nicole Clark on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.