This Incredible VR Film Takes You on an Ayahuasca Journey to the Amazon

You are sitting in a canoe on the Gregório River as a voice gently narrates the story of Hushahu, the first Yawanawá woman to become a shaman. The narrator translates for Hushahu as she speaks about her tribe of roughly 3,000 indigenous peoples spread across Brazil, Peru, and Bolivia and the sacred tradition of taking the medicinal Uni tea (better known as Ayahuasca) in order to convene intimately and spiritually with the forest in which they live.

A long bridge divides the outside world from the tribe. You stand in the middle of it, waiting to be invited in. You are transported to Tatá’s side—the Yawanawá elder shaman who is over 100 years old—as he lies in a hammock, surrounded by family. Hushahu takes the Uni tea. She tells you how the forest comes alive to her and exchanges energy with her. She tells you the challenges of staying under the influence of Uni tea for several months, under Tata’s guidance, as part of her shaman training.

You are then transported into the forest as it dissolves into a gorgeous, gently undulating field of thousands of light points—it’s like standing in the middle of a Pointillist painting. You are lifted slowly into a massive tree, where the infinite view fills you with awe, making the small hairs on your arm stand on end. The path of your vision lights up the environment with the luminescence that Hushahu is describing. As Hushahu narrates the challenges of Ayahuasca, you are lowered into a stream, the water serenely rippling over you. You are there.

This is Awavena, a 17-minute “mixed-reality” work that melds augmented reality, 360-degree film footage, and virtual reality. It was funded by the Sundance Institute, produced by Nicole Newnham and directed by Lynette Wallworth, a duo whose previous VR film Collisions won an Emmy. Awavena screened in January at Sundance, but has been under production even through this week as the team tweaks it based on emerging VR technologies. (It’s currently being premiered to the world at the Venice Film Festival.) It’s Hushahu’s story, but more than that, it’s a remarkable attempt to give the viewer the experience of physically being in the Amazon, drinking the Uni tea, and feeling the energy of their rainforest.

The project began in 2016, when the Yawanawá chief, Tashka, viewed Collisions and realized the technology could be used to help outsiders understand the Yawanawá’s sacred traditions. Tashka immediately asked Wallworth to come to Acre, Brazil, to film their community, as their shaman Tatá was in failing health. They began filming in 2017. “We had an instant compatibility,” Wallworth told me when I met her at the Technicolor Experience Center in Los Angeles. “Tashka told me he and I are two dreamers, and that we see things that not everybody sees.”

As documented in the film, Tatá was one of the spiritual centers of the Yawanawá tribe, having survived years of slavery during which missionaries and rubber tappers threatened their culture. Tatá preserved the Yawanawá spiritual tradition even as the tribe faced extinction in the 1980s. He trained Hushahu to be the tribe’s first female shaman, and in doing so, emboldened other indigenous tribes in the Amazon to finally initiate women as shamans.

Hushahu told me over the phone (translated by her husband Mayaisa) that being filmed was “scary and beautiful at the same time.” Most of the footage looks candid, in classic documentary style, as if the camera is never there. But in select moments—at the very beginning and at the very end—Husashu gazes directly into the camera. It feels like she’s really looking at you and speaking to you, an intimacy ordinary 2D films can’t match. “I couldn’t explain to her exactly what I was doing,” Wallworth said. “She just had to trust, which is something she said to me today, she trusts me.”

Chief Tashka and his wife Laura are both co-producers on Awavena, and worked with Wallworth throughout the process. “I was a conduit for what they wanted to express—we don’t overstep, we constantly check in,” Wallworth told me over the phone. Her team was constantly sending footage to Tashka, who would give feedback and approval.

The virtual reality rig is a bit uncomfortable at first, a bit alien—one of those giant protruding masks you see in VR ads that makes it feel like you’re about to go skiing. Instead of earpads that cancel outside noise, the headphones have ancillary tabs that rest on top of the ears, making the sound feel more ambient and realistic.

The environment becomes immersive because Awavena teaches you to see past film as a static, rectangular field. It is strangely intuitive the way the film not only guides you to look around in a complete 360-degree field, but also prompts you to pay attention to one particular element at a time. It happens first with footage of a young girl tracing lines in the dirt path with a knife before throwing the knife across your visual field. Your eye instinctively follows the knife, and you realize you are not simply watching a scene on the path but rather standing in the middle of that pathway.

The cues are also auditory, like the sound of the crackling fire coming from a distant left or right, prompting you to turn to toward it as you would in real life. Wallworth took great care to ensure these transitions were never jarring or phobia-inducing—unlike VR films like theBlu, a Blue Planet style simulator which wasn’t meant to be scary but could easily trigger drowning-related phobia. (It nearly gave me a panic attack the one time I tried it.)

Most importantly, virtual reality enables you to have a physical experience similar to that of the Ayahuasca ritual. Wallworth says the Yawanawá’s sacred Uni tea ritual is one of “visioning” that bears similarities to the functionality of virtual reality. “It opens a portal, carries you to a place you’ve never been, intensifies colors and sound,” Wallworth said in a behind the scenes video of the making of Awavena. “You’re moving without your body, you’re given a message, and then you return.”

The physical geography is also extremely important, as the tradition is about convening with the Yawanawá rainforest specifically. It could not be properly expressed without that sense of place. Hushahu agrees that this film could not have been done without the technology. “Perhaps a bit, but not the way it is, completely not,” she said. “I hope this opens the world to get to know the energy that’s there in the forest. It’s good, the way the movie is bringing this message. You feel like you’re there, it’s really like taking the Uni. It’s different.”

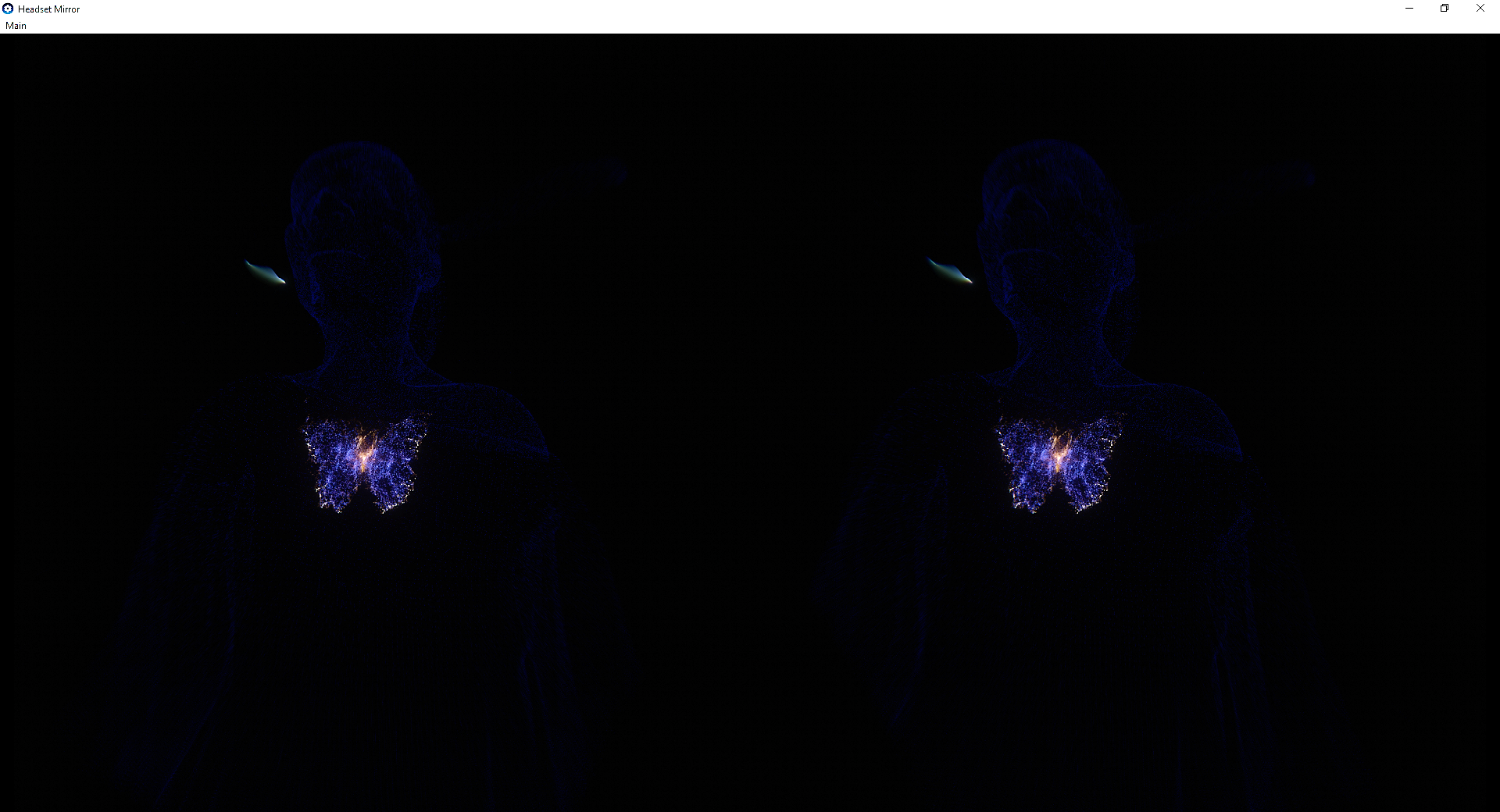

Though I did not have the opportunity to test it, the true screening of Awavena will include an optional second half where viewers could consume an herbal drink (not the real Uni tea) to enter the “Blessing Space.” Viewers will then be given a portable VR rig with a backpack in order to traverse the Yawanawá forest, translated through LIDAR scanning, in earnest. The forest will be responsive to the movement of the person in the VR rig in a screening room that has been set up to facilitate exploration.

“What they’re learning from this medicine is specific to their forest,” Wallworth said. “We brought it into a game engine, Unity, and made it responsive. It’s completely specific. Every tree is really a tree, every plant is really a plant from the Yawanawá forest, but it’s broken into points that make it look like it’s ethereal. I was dogged about the fact that it needed to respond to your gait, because of what Tashka had said, that the forest is ‘aware of you.’”

“It was very beautiful, I got emotional,” Hushahu said of the second half, “I felt a connection, something very real with the medicine and with the forces when we drink this Uni. The spirituality.”

“This movie is about Hushahu’s message and Tatá’s passage,” Mayaisa added. “It seems like a part of him is there.”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Nicole Clark on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.