Instagram’s Boundary-Pushing Documentary Photographers

In 1967, MoMA curator John Szarkowski organized “New Documents,” an exhibition featuring Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and Garry Winogrand. The exhibit presented a new generation of photographers who were making documentary work with a more personal approach. These photographers went on to have a remarkable influence on contemporary photography and their legacy continues to shape visual representations of the world. A decade later, Susan Sontag added a new layer to the conversation in her apt, yet scathing essay “On Photography,” which heavily questioned documentary (or any genre of) photography’s ability to tell the truth.

Fast forward nearly 50 years and it’s no longer a new idea that all photographs contain some kind of bias, whether they’re digitally manipulated or slanted by the photographer’s cropping, framing, or decision to be there. So with that common understanding, what place does documentary photography hold today? And how can it, in an evolved climate of skepticism and increased media literacy, inform its viewers with some grain of truth or authenticity? Or does it even need to?

The majority of the following six photographers do not consider themselves “documentary photographers” in the traditional sense. But what brings them together is how they borrow from the traditions of documentary photography, their ability to turn the genre on its head, and their use of Instagram to get their work and ideas into the world with a sense of urgency. In some cases, they incorporate art-photography, fashion, and other genres with a more fluid approach, while others are deeply and self-consciously personal.

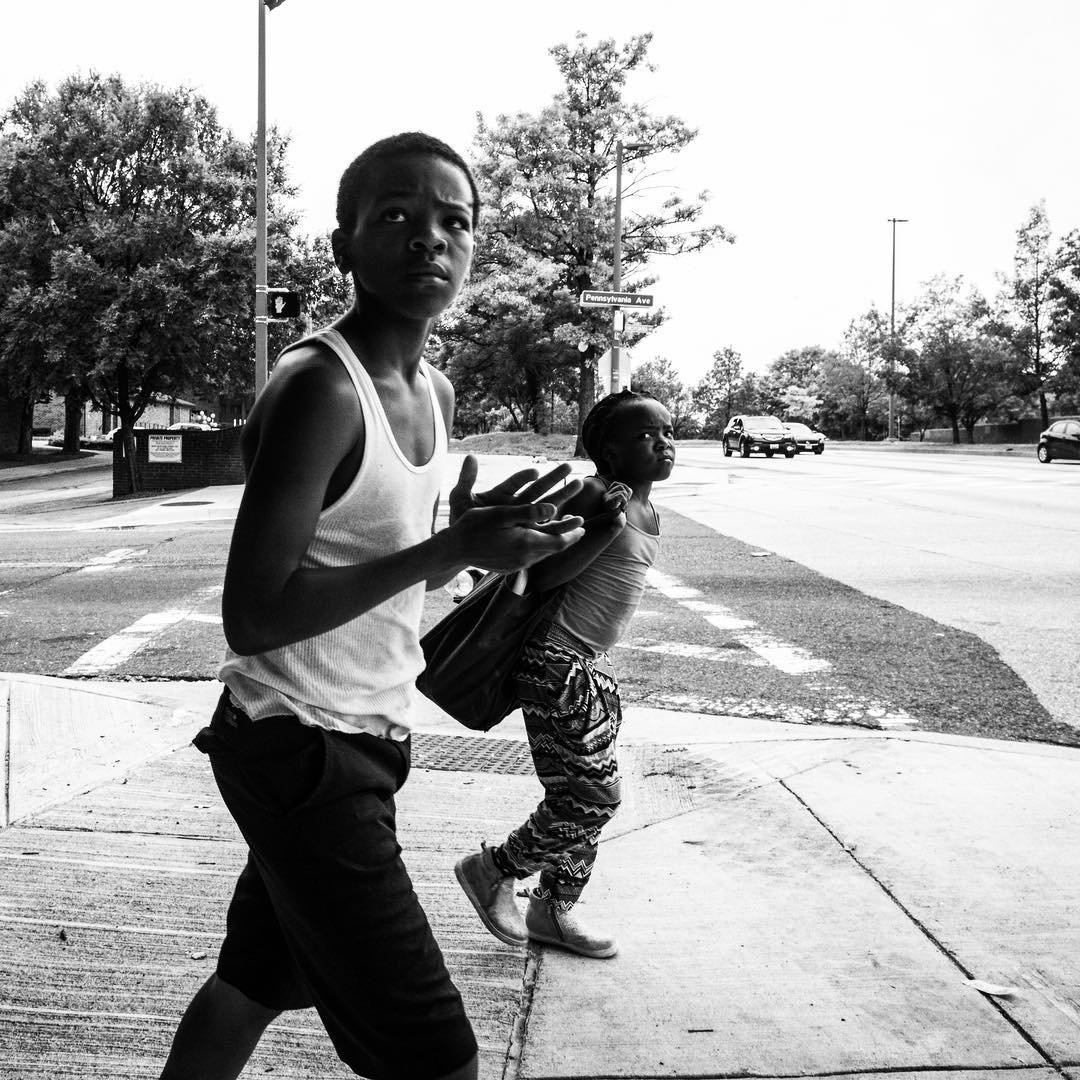

Devin Allen

Devin Allen gained attention for his work in 2015 with his now-iconic images of the Baltimore protests responding to the police killing of Freddie Gray. After cops broke his Fuji XT1, he began shooting with his iPhone, uploading photos to Instagram. He quickly caught the eye of editors at BBC, CNN, and Time.

Allen originally aspired to be a portrait and fashion photographer, but his experience at the protests propelled him to take a more “fly on the wall approach,” photographing his community in Baltimore as a passive observer. These photos evolved into A Beautiful Ghetto, Allen’s first monograph, published in 2017 by Haymarket Books. Allen’s work asks viewers to look beyond stereotypes of “the ghetto” perpetuated by outsiders. Instead, he wants you to see the many, varied layers of his community.

While Allen’s approach could be considered the most traditionally documentary work of any photographers in this feature, Allen prefers not to categorize himself within any genre. “I’d rather not label it,” he says. “My goal is to create conversation. That’s it. I hate naming or describing my art because I want people to digest it freely without me telling them what it is.”

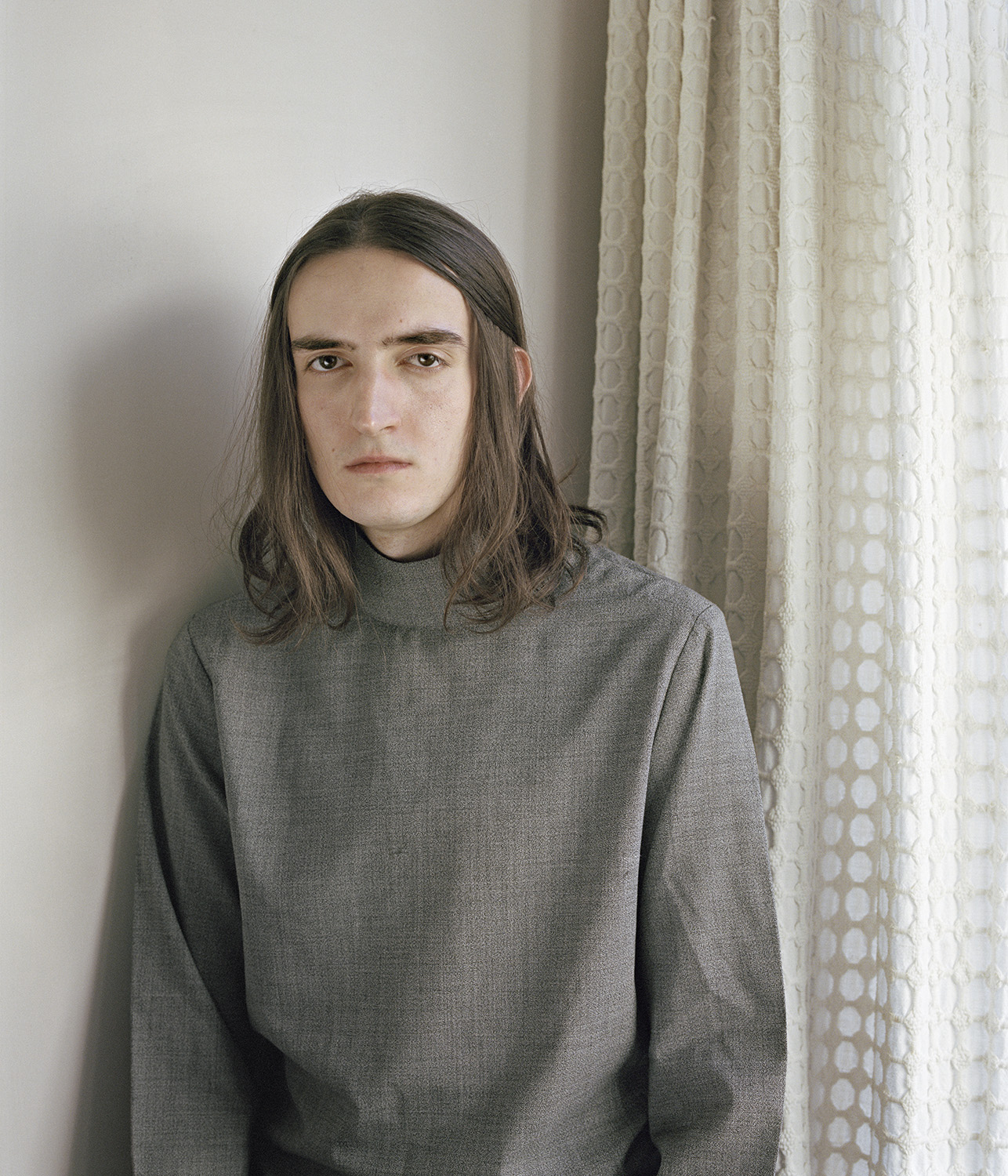

Anne Sophie Guillet

Anne Sophie Guillet’s Inner Self is a series of portraits that address gender’s many malleable dimensions. Their formulaic approach—photographed at the same distance from above the waist gazing directly into the lens—emphasize the ambiguity of their identity. The subjects are Guillet’s friends, casual acquaintances, and even strangers. She photographs them with a democratic anonymity that brings them together and invites comparison without judgement. In the artist’s words, the people in her pictures “escape a strict binary view of how they might be expected to look based on their sex or gender.”

Far from Devin Allen’s fly-on-the-wall style, Guillet’s work isn’t “documentary photography” in the traditional sense of the word. There’s a level of staging and the photo sessions, often over an hour long, allow time to gaze through the lens establishing a shared connection with the photographer and viewer. Yet it nods to traditions ranging from August Sander to Diane Arbus in its use of a serialized, yet empathetic approach to study a community. “I want to enable individuals that do not conform to a specific identity to feel a sense of being represented,” says Guillet. “I want to break the stereotypes and show that there are different ways of living our lives as human beings.

John David Richardson

John David Richardson makes personal photographs about the impact and trauma of poverty on his life and spirit. His series Someday I’ll Find the Sun toes the line between documentary, staged narrative, and artful portraiture. It’s not exactly a self portrait in the literal sense, but each image is a reflection of his family or himself. The photograph Catfish and Cigarettes, 2017, crystalizes this hopelessness. It features a dead fish laying across a table next to an ashtray of a hundred cigarette butts in front of an air conditioner awkwardly crammed below a window. Volleyed with sad portraits and other scenes of working-class Americana, Richardson consistently drapes his images in warm golden light. The slow-burning glimmer in his photos makes one think that things might actually get better.

While the work is about poverty, it breaks from many literal, historical representations. Instead, Richardson’s work turns inward as a metaphor for his own struggles.

“Photographs have the potential to reinforce and perpetuate stereotypes,” says Richardson, “and I think that it’s important to me to approach this subject with empathy and a willingness to listen.” While many of the people he photographs are strangers, the camera helps build a relationship of mutual trust. “I hardly ever photograph someone the first time we meet,” he adds, “I’m interested in a degree of intimacy that simply can’t happen that quickly.”

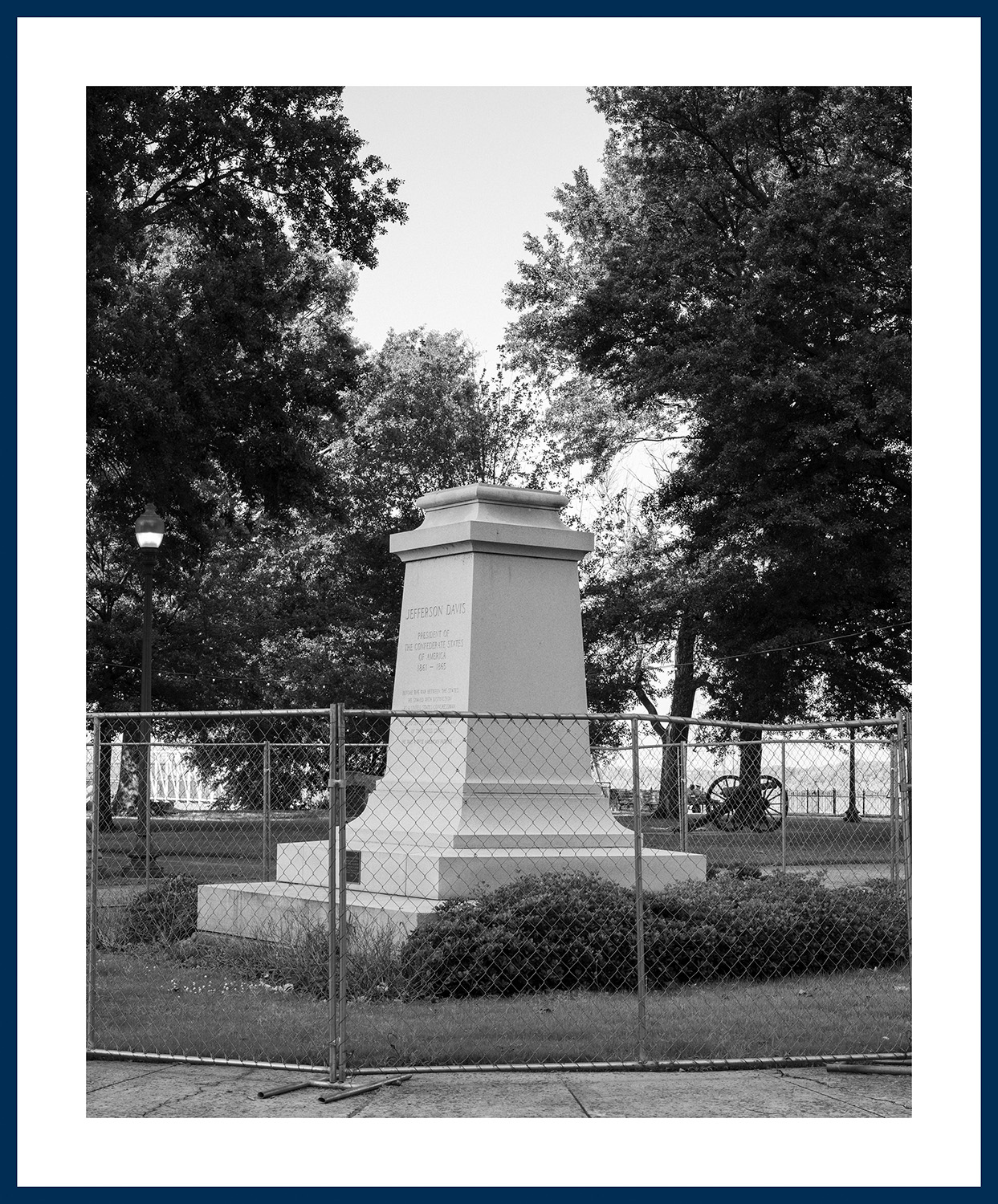

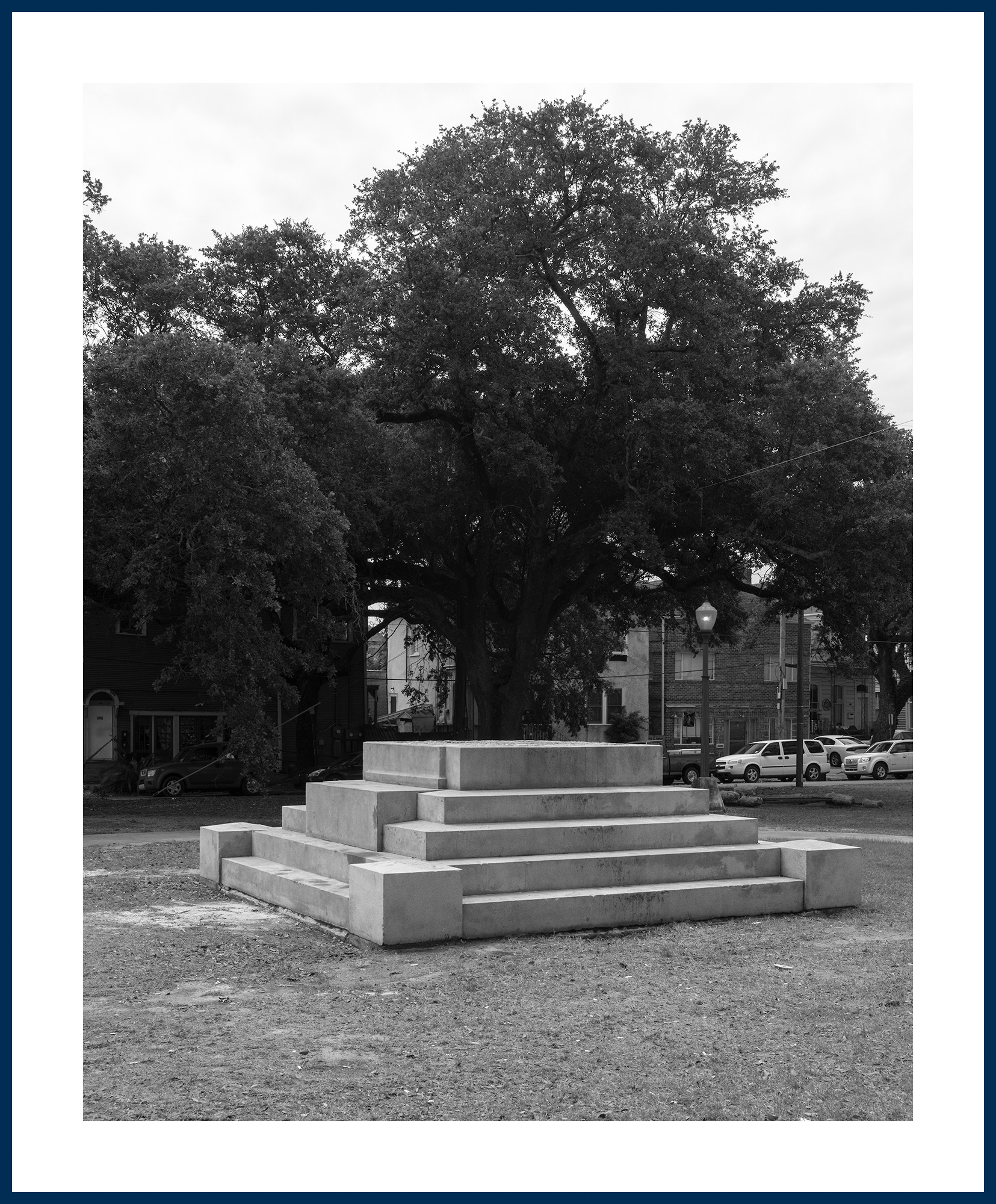

Matthew Shain

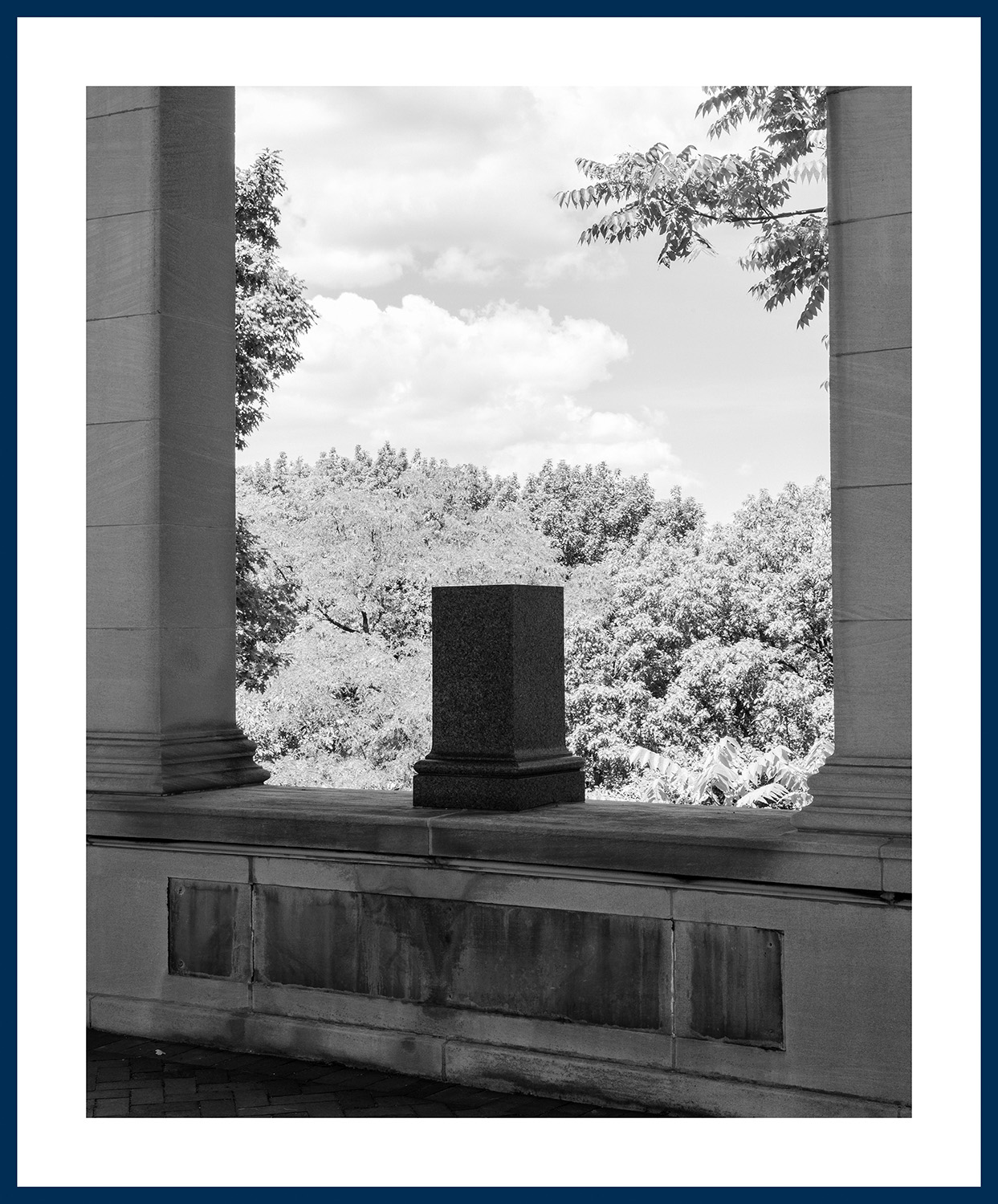

Matthew Shain’s Post Monuments is a series of the spaces that remain when Confederate monuments have been removed from public view. Their absence somehow elicits more visual tension—the legacy of racism and slavery hanging above their empty pedestals of marble and concrete. They’re photographed cold and serialized, not unlike Bernd and Hilla Becher’s classic images of industrial architecture in the 1960s. The images embody the heavy ghosts of our country’s past—one that, even with the removal of these structures, we cannot escape.

“I haven’t necessarily thought of this project as a documentary one,” says Shain, “but I wouldn’t exclude it from that genre either. When I think of documentary photography, I think of things like narrative and sequencing—storytelling—but I don’t see those qualities as being a part of this.”

However, Shain recognizes that the images serve as records of a very specific and awful time in American history. “Documentary photo can be approached in myriad ways,” he adds, “but hopefully always aims to provide a critical eye towards its subjects, so that we can better understand that subject and hopefully ourselves, our myths, our communities, and society.”

Michal Chelbin

Michal Chelbin combines elements of social documentary, traditional reportage, fashion, and fine art to create a hybrid genre of photographic storytelling. You can see it in her stories for Time, California Sunday, or the New York Times Magazine. It’s evident in her collaborations with Dior and Pierre Cardin. And it comes through in her personal series on Ukrainian prisoner portraits and military boarding schools. “My vision is mythological,” she says, “and my work is my way to address universal themes like the pursuit for glory, family issues, and the complexities of youth and adolescence.”

Chelbin’s work is probably the most staged and constructed of all of these photographers. Nearly all of her photographs are staged and scouted for lighting, location, casting, etc, consciously blurring truth, while giving a glimpse into a world often absent from popular view. “Of course there differences,” she adds, “for example, in fashion and editorial there is a ‘client’ (some time on set with me), while in personal work there isn’t one. But I try to approach it like my personal work and get as much control as I can on the casting and locations.”

Abdo Shanan

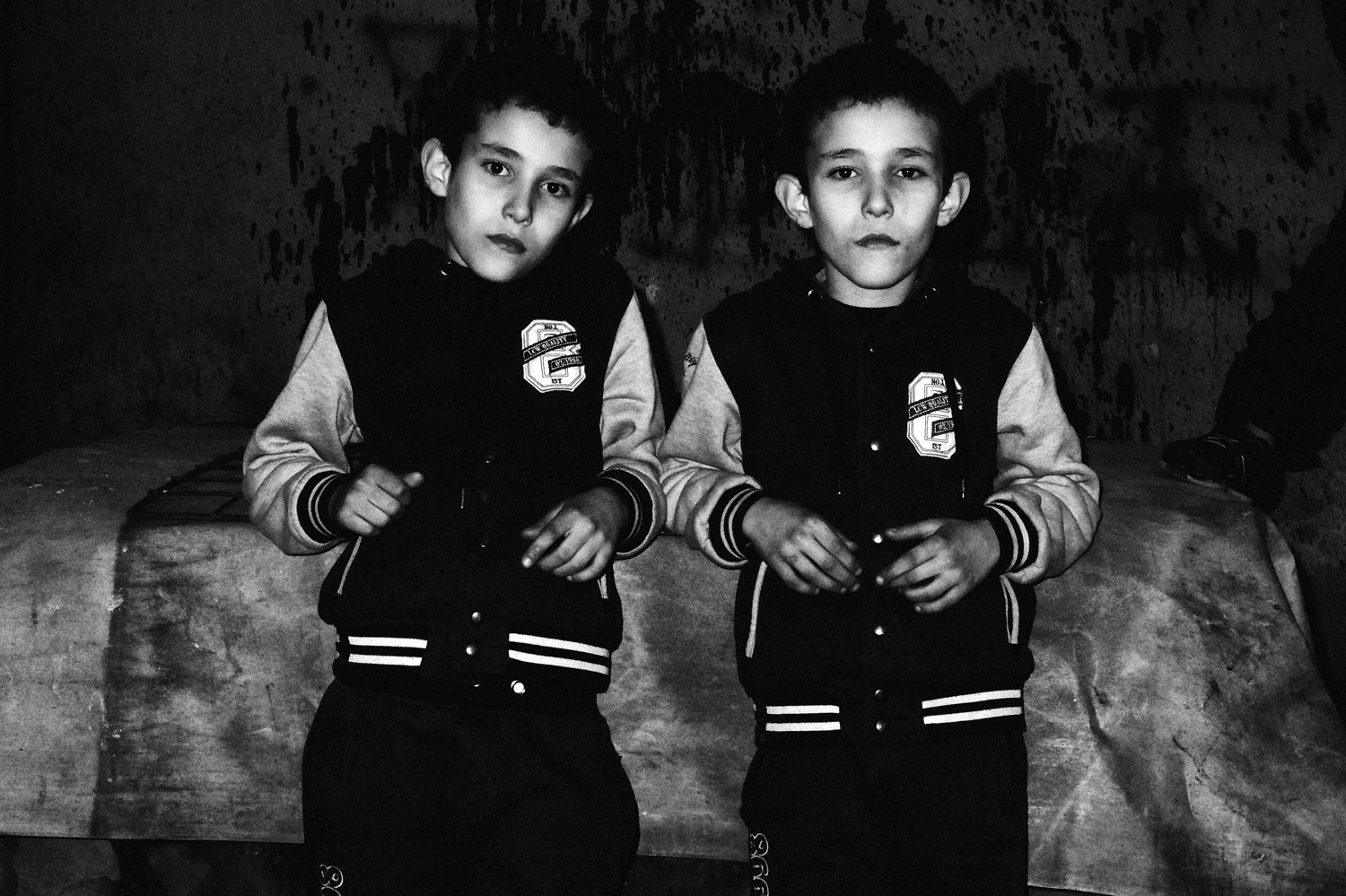

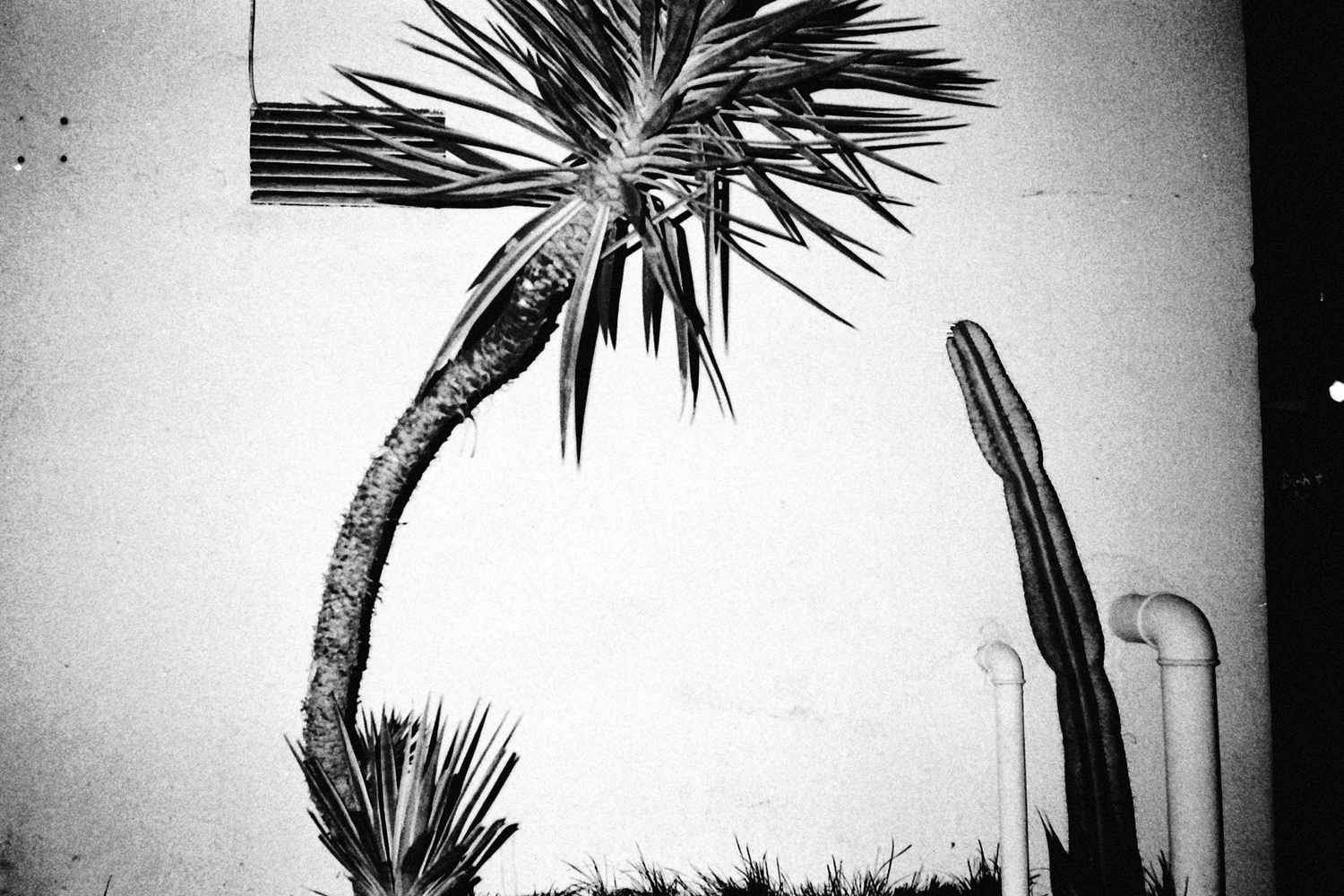

Abdo Shanan makes dark, grainy, often abrasive black and white photographs—shot fleetingly from the hip and other odd angles—that describe his feelings of being in exile. The photographer was born in Algeria in 1982, but moved to Libya in 1991 at the start of the civil war, and returned in 2009. His recent project, Diary: Exile, questioned his sense of belonging, growing up with a charged history among children of the upper echelon. “It helped me to deal with trying to fit in my society and to find my voice,” he says.

Writer Kaelen Wilson-Goldie, in Aperture’s “Platform Africa” issue last year, aptly described Shanan’s work as a cross between Nan Goldin, Diane Arbus, and Roger Ballin. It’s strange, uncomfortable, and incredibly raw. In one photo, twins identically dressed in baseball jackets, lit by a harsh flash, stare with equal parts concern, equal parts disdain. In another, a tropical tree and cactus, blasted at night with the same jarring flash, bend towards each other as if trying to embrace, communicate, or share a secret. Still, in other images hands cover faces, lovers wrestle on the ground, there is an overwhelming sense of chaos.

“If documentary photography means producing a series of photographs that have a visual accuracy of people, places or objects,” says Shanan, “then I am not a documentary photographer. In my work, I ask questions. I doubt the accepted ‘norm’ for the society from which I produce a series of photographs that for me forms a language that express me and could reach out to others that are seeking a voice or a place to fit.”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Jon Feinstein on Instagram.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.