The Story of Canada’s Infamous Helicopter-Hijacking Bank Robber

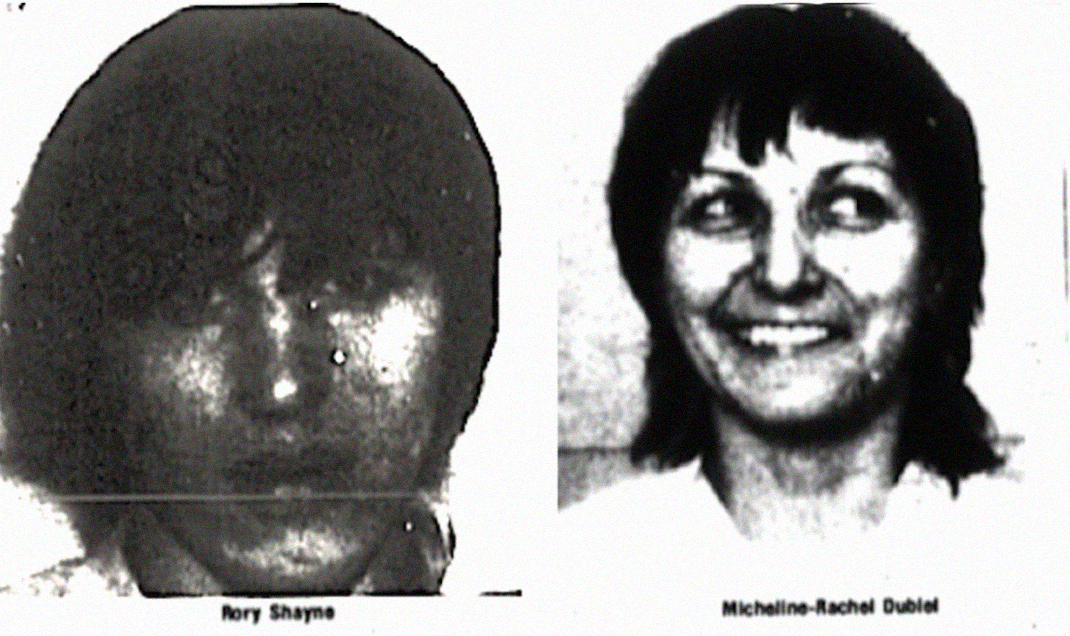

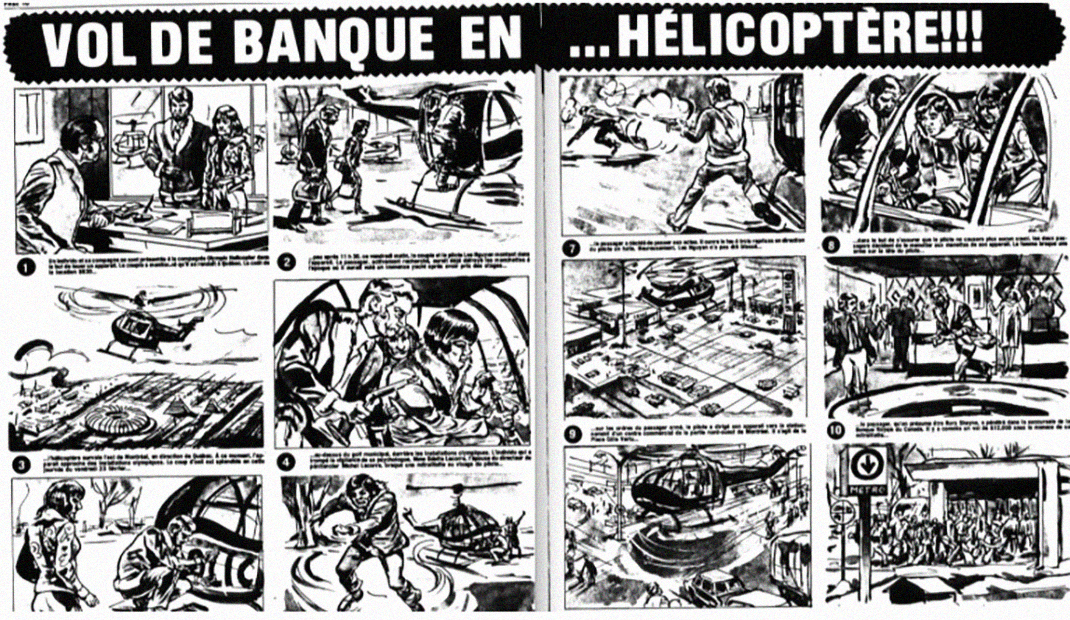

On February 23, 1979, Rory Shayne and his girlfriend Micheline-Rachel Dubiel stepped out of a hijacked helicopter in the parking lot of a strip mall in Montreal. Shayne was wearing a black leather jacket and armed with a chromed-out submachine gun that once belonged to the Chinese National Guard. Dubiel, later charmingly described by a witness as “very ugly,” was also armed and sporting her very own red leather outfit. Looking more like Sid and Nancy than Bonnie and Clyde, they entered a Royal Bank and got to work, pilfering the place of more than $12,000.

Meanwhile, back in the chopper—adorned with fake “Police” lettering—pilot Nguyen Hiu Lee, a veteran of the Vietnam war, waited for the couple in handcuffs. Earlier that day, Nguyen, who worked for the Olympic helicopter tour company, had been hired to fly them to Quebec City, though he quickly became an unwitting participant in one of the most brazen crimes ever committed in Canada. After exiting the bank, Shayne boarded the helicopter and instructed Nguyen to fly northeast, landing near Sauvé Metro station, where he and Dubiel would disappear underground.

It was a brilliant heist not only in terms of planning, but execution, and just one in a long list of dramatic crimes and disappearances orchestrated by a 28-year-old Shayne. Yet, for all of his bravado, Rory Shayne was and remains a mysterious figure in the underworld he occupied. We spoke to Shayne’s lawyer, his teacher from prison, and a fellow inmate about the criminal legacy of a forgotten criminal mastermind.

The Bank Robbery Capital of North America

Rory Shayne figures prominently in D’Arcy and Miranda O’Connor’s book Montreal’s Irish Mafia: The True Story of the Infamous West End Gang, but was an outcast even among that motley crew of thieves and drug dealers.

“Dunie Ryan, who was the head of the West End Gang, didn’t want to have anything to do with Rory, he thought he was crazy and that he would just bring heat on him,” D’Arcy O’Connor says, citing his wild MO and propensity for buying heavy weaponry with money from bank jobs.

“There was a whole Bonnie and Clyde persona with him and Micheline, which I also found fascinating. She was very much in on it and she also escaped twice from the women’s prison. They were like peas in a pod. [During the helicopter heist] he was all in black leather and she was all in red leather. How glamorous can you get?”

Shayne’s flair for theatrics meant that he stood out even in Montreal, a city that had become home to as many as 900 bank heists annually, and was once labelled by the LA Times as “the bank robbery capital of North America.”

Peter Fryer, a native Montrealer who says he connected Rory with the West End Gang, was being held one cell down from Rory at the Leclerc penitentiary in the late 70s. “He was a very shy, very nice guy—very reserved. A bit different, you know? He used to stay in his cell and meditate. One time, I walked by his cell while he was meditating and kicked the door, so Rory chased me around the common room for a while, because he was so pissed off. But after that, we became good friends.”

According to Fryer, Shayne’s impulse to escape extended far beyond prisons and banks and could not even be bound by the parameters of space and time.

“Rory was into stuff like astral travel; he thought he could go into his mind and travel around. In his cell, he thought he would leave his body and just go downtown—like that! That’s what he was into.”

That, and guns. When Shayne finally resurfaced months after the helicopter heist, he was living in a Saint-Leonard apartment with Micheline-Rachel. Upon entering their fugitive love nest, police found it stocked with thousands of rounds of ammunition and a military-grade arsenal. “When the cops broke in at night, while Rory was sleeping, they found thousands of rounds of ammunition and calibers. He could have held off an army,” O’Connor says. “He had a bazooka and all kinds of stuff.”

The Education of Rory Shayne

But D’Arcy O’Connor’s connection to Shayne is much more intimate than just research for a true crime book. He got to know Shayne while teaching creative writing to prisoners of Leclerc. “He was a neat guy, I liked him,” O’Connor says, describing the far-fetched stories that Shayne would write. Like one about a bank robber who hijacks a sailboat and holds a honeymooning couple hostage after a shootout with police, only to be apprehended by the US Coast Guard.

Years later, while doing research for his book, O’Connor realized that this was actually a work of non-fiction and that Shayne had not only been the author of this short story but also of the actual crime it described. “He was the smartest student in the class,” O’Connor laments. “He could have been working for a bank instead of robbing one—very, very clever guy.”

So clever, in fact, that he managed to escape from Leclerc while on a day pass with a prison psychologist in downtown Montreal. It was after this escape that Shayne pulled off the helicopter heist and a rash of others, raking in an estimated $260,000. “I remember arriving one morning and he wasn’t in class,” O’Connor says. “I asked the other guys, ‘Where’s Rory?’ and they all started laughing and said, ‘Over the walls!’” Needless to say, O’Connor was disappointed with the sudden departure of such a promising student. “I’d point out that he hasn’t handed in his last assignment, he still owes me an assignment!”

Apparently, Shayne also had a knack for art. An instructor from a prisoner art program once described him as “a promising beginner” and “a very talented and very meticulous guy, capable of a very high concentration.” Unfortunately for society, Shayne’s talent, meticulousness, and high concentration were all channeled into violent crime.

A Child of Violence

Though his creativity and intelligence were undisputable, pretty much everything else about Rory Shayne is an enigma. For starters, his real name wasn’t even Rory Shayne, but Burkhard Bateman, born in Germany to a Canadian father and German mother (both of whom ended up in mental institutions in Canada) who put him in an orphanage at a young age. Rory, described in adulthood as “a child of violence,” was coming to Canada as an already damaged nine-year-old.

“His story is very sad,” says Rory’s former lawyer Gary Martin, who Rory once tried to shoot in court. “Rory was adopted from Germany and brought over to Canada by his aunt, I think, who was a nurse. He came to Canada on a ship. The man accompanying him was a police officer and Rory told me this story that he had a toy gun and this cop told him that this was not good for him and threw the toy gun overboard. He always told me, ‘That’s how I began my life of crime.’ He obviously took it to heart.”

The scars from Shayne’s childhood were not just psychological. “He had scar tissue on his chest and up to his neck,” Martin remembers. “When you spoke to him, he always held his shirt closed. He would always come to court holding his top button with his hand so that his scars were not showing.” As D’Arcy O’Connor explains in Montreal’s Irish Mafia, these scars came from Rory’s foster mother cutting his face with a kitchen knife when he was four years old and then trying to make it look like an accident by scalding his face and chest with boiling water.

Courtroom Hostage-Taking

During one court appearance, however, Shayne was hiding more than scars. On December 15, 1981, Shayne appeared in Quebec Superior Court to set a trial date and to be arraigned on a multitude of charges, including an attempted prison escape and hostage-taking that took place when he returned to prison following the helicopter heist. Before the hearing could begin, Shayne burst out of the detainee room holding two security guards hostages. He brandished a small-caliber gun, pointing it at presiding judge Paul Martineau (once Minister of Mines and Technical Surveys under John Diefenbaker), who promptly ran back into his chambers, and finally aimed it at his lawyer Gary Martin, insisting that he could not go back to prison.

“I said, ‘What are you going to do now, shoot your lawyer?’” Martin recounts. “I was being a bit sarcastic, but I was trying to negotiate for a woman hiding under a desk to walk out of the room. That was my main concern.”

Because Shayne had once used a fake gun made out of soap and shoeshine to break out of prison, Martin was sure his client was bluffing. He wasn’t. The weapon was a .22 caliber starter pistol, like the ones they use for track and field, but it had been converted to a .38. Shayne pulled the trigger. “The gun misfired twice, then the guards jumped him and a shot did go off, into the floor. I got two lucky misfires. Usually, you’re lucky if you miss one—not two. The third one went into the floor.”

All of which begs the question of how an inmate being transferred from prison to a courthouse in shackles was able to conceal a semi-functional firearm. There were two competing theories at the time: that the gun had been hidden in the courthouse beforehand or that Shayne hid it inside of his rectum. Armchair forensics point to the latter, however, which could also explain why the gun jammed when he pointed it at his lawyer.

“Maybe it was a Vaseline overload,” Martin laughs. “Usually a gun misfires because of humidity. Bullets have detonator caps and when the cap is punched, that’s what detonates the powder in the shell and the casing itself. That’s what probably happen, if it did come from his butt. That’s probably the cause of my lucky misfires.”

Rory Shayne had once again managed to outsmart authorities under impressively difficult circumstances, but the wheels of justice did not stop turning. “Rory got up a few minutes later and appeared in front of the judge and set a date,” Martin recalls. “He had a few little red marks on his face at that point.”

How to Disappear Completely

In 1982, Shayne was convicted and sentenced to life in prison for the attempted murder of Judge Martineau, ending up in a supermax prison in Saskatchewan by 1986. Not long after, Shayne was deported to Germany and his trail goes cold, save for one clue from D’Arcy O’Connor that he says was never fully substantiated.

“About a year ago, a woman got in touch with me,” he says. “It turned out her mother was an old girlfriend of Rory’s who kept in touch with him after he was deported to Germany. She told me after he was deported, her mother and Rory still corresponded and she was quite smitten by him. I don’t have any of the letters and I never heard back from her. That’s my last connection to Rory.”

“That’s what I don’t understand,” says his old prison buddy Peter Fryer. “All of a sudden, he just vanished into thin air. I don’t know. He came into some money when he did the bank robberies and that was it. I haven’t heard from him since.”

Neither has his former lawyer Gary Martin. “Some people told me he passed away,” he says. “It’s a bit like the guy who jumped out of the plane with the money in the States. When you don’t know what’s happened to people, there is always mystery attached. Nobody knows what happened.”

Kristian Gravenor spends “literally every single day” looking at newspaper archives and digging up old stories from Montreal’s sordid past, many of which have ended up on his blog Coolopolis and his book Montreal: 375 Tales of Eating, Drinking, Living and Loving. Throughout his research, Gravenor has also become increasingly perplexed by the mystery of Rory Shayne.

“If you want to talk about Rory Shayne as being an Irish mobster, it’s a bit of a fucking stretch,” he says. “To be in the West End Gang, you kind of have to sit in the damn bar and laugh at the idiot’s jokes, then you’re OK. But Shayne was sort of a weirdo loner who was off on his own. This guy had a vision.”

For Gravenor, this incongruity has come to define Shayne even more than his impressive criminal record. “That’s what I think the legacy of this guy is. It’s the mystery of what drove him; if he wanted to show off that he was a brilliant criminal, who was he showing off to? Who was the circle? What was his crowd? […] To have a higher IQ or the ability to think of something creative and possibly brilliant, you probably shouldn’t be in the world of low-down crime. It seems that the world would have better things in store for you than that.”

Rory’s old teacher is a little more cynical. “He’d probably be in his late 60s now and living in Germany, unless he robbed a Bundesbank and got off to somewhere else,” D’Arcy O’Connor muses. “Who knows?”

Wherever Rory Shayne is today, he bears the scars of a life lived in defiance of the brutal limits imposed on him from day one. Abandoned by his birth parents, disfigured by a caretaker, and shipped to Canada for what would essentially become a life behind bars—Shayne was as much a victim of his circumstances as he was manipulator of them. Like Sisyphus with his rock, Rory Shayne pushed his way through a violently absurd existence, creating his own purpose by pulling off impossible heists, defiant jailbreaks, and voyages to neighbouring dimensions from the confines of his cell. Alive or dead, one thing is sure; Rory Shayne left the world in a more chaotic state than he found it in.

With files from Miranda O’Connor.

Follow Nick Rose on Twitter.

Sign up for the VICE Canada Newsletter to get the best of VICE Canada delivered to your inbox.