The Bizarre Saga of the Man Cracking Down on ‘Fake Homelessness’

This article originally appeared on VICE UK.

Quick question: How many homeless people are there in Torquay, England?

Just as a ballpark. It’s a town of about 65,000. It’s a seaside resort town on the English Channel down in south west England. Maybe there are ten? 20? 120?

The point is that this seems like a question with a proper answer, doesn’t it? Like the starting point of an investigation, rather than the entire investigation itself.

I’d thought so, too. Until about 25 minutes ago.

“They’re pretending because they get funding to combat homelessness. It’s the biggest modern-day sham! Homelessness is a huge business! Fake homelessness is even bigger! So why on earth do homeless charities have any interest in reducing the number? Honestly, Gavin, you play this one right, and you can have yourself a really big story here.”

Ashley Sims is my new vigilante friend. He has ruffled a lot of feathers lately. He says the local paper is against him, that the council hates him, and that homeless charities denounce him. He is loved and despised throughout the town—though the exact quantities of each emotion remain unclear.

His story cuts across local politics, perverse incentives, and the limits of the welfare state, to arrive at that uniquely unloveable point where the caring classes tacitly collude with the managerial classes to create a mirage of both caring and competence.

The problem with Sim’s story, though, is that I don’t entirely believe it. When I get off the phone with him, finally, some suppressed spinal nerve pings in me, journalistically. Because things that sound too good to be true are the things that are most gagging for printing. A dilemma.

Is Torquay actually a hotbed of corruption? Or is Sims actually just a troubled, makeshift hero gradually coming undone?

Some known facts:

Late last year, Ashley Sims was running one of his restaurants. There was a homeless man begging outside the coffee shop beneath him.

“Anyway, I did a bit more research, and I found out that all of them had a place to live. Nearly everyone was a professional beggar,” he says, convinced, over the phone. “They’d go and get their sleeping-bag, go into town for a couple of hours and then come back once they’d made enough for their next fix.”

Like most in the town, he’d noticed an uptick lately. People were saying the town was rundown, that the city center was dying. The evidence? Homelessness had exploded. So Sims came up with a plan. The sort of plan someone who has no background in a topic comes up with at a pub, before someone tells them it’s preposterous, dangerous, or just won’t work.

“There’s only one thing these people don’t like—having their picture taken. So I put up signs around town, warning people that they could have their picture taken.”

Over the course of a couple of days, Sims took pictures of all the homeless in town—around 20. Then, through a network of locals, he identified as many as he could. Then he went down the local job center. “I said, ‘Do me a favor: run a check on these—see if they’re in receipt of any benefits.”

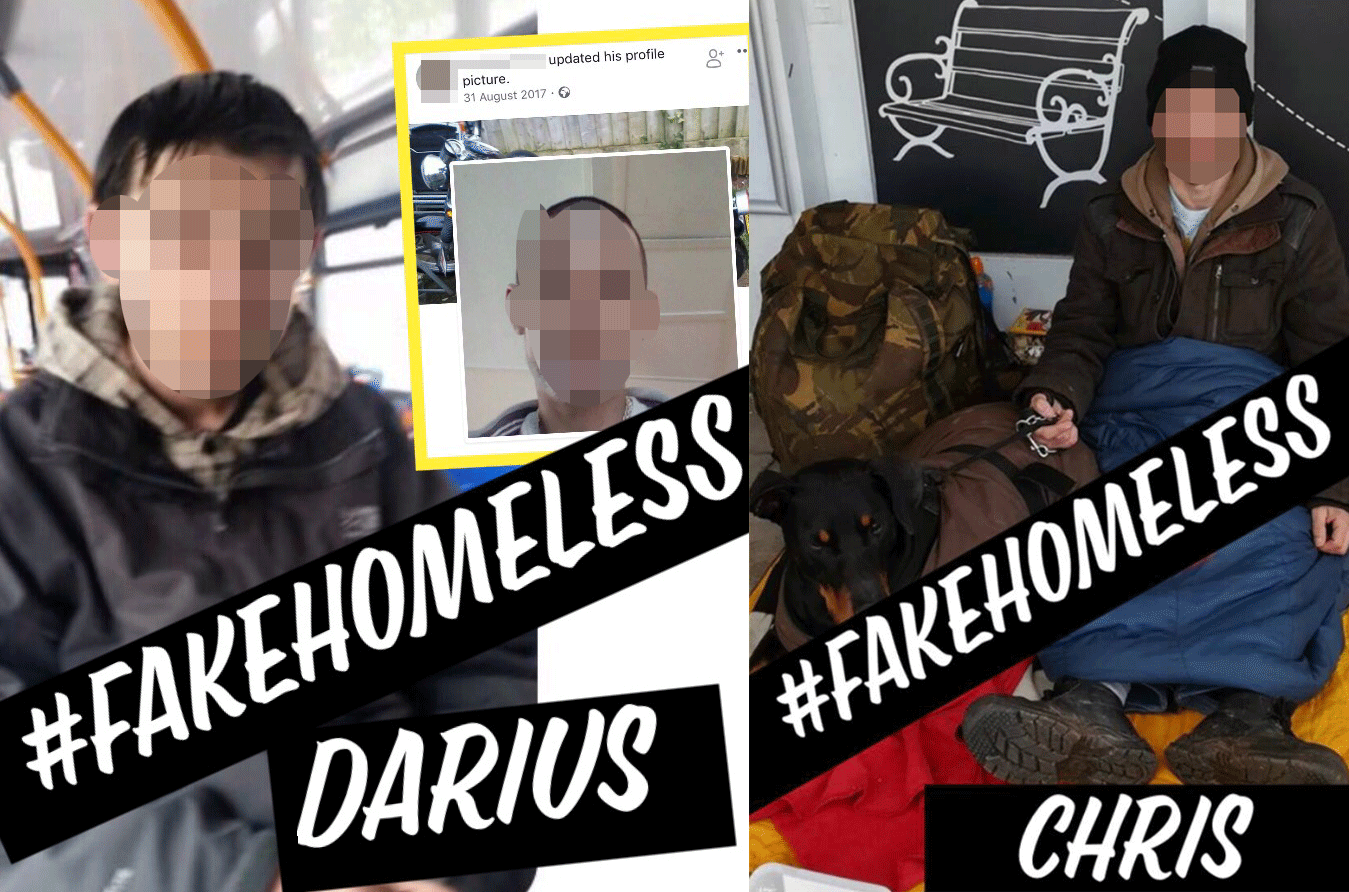

He published the frauds on his Facebook page, Fake Homeless. Magically, overnight, the number of homeless in town went down, says Sims, “from 20 to six.”

Then stuff started exploding. He was widely denounced, the press began calling, he got invited on talk shows, where he’d be put head-to-head with local homeless charities, who had no time for his methods. Before long, Ashley Sims found himself in local council meetings.

“I had seven photos and names I was going to expose as fake homeless on Thursday. So, the council called me on Monday at 9:30 AM for an emergency meeting. They said: ‘We can’t let you proceed because we’ve learned that one of the people you are planning to expose is really homeless.’ So I said: ‘Apologies—please give me the name of that person so I can correct it.'”

“They said: ‘Oh, we can’t do that—data protection.’ So I said: ‘Please God, don’t let this be a setup and you’re about to leak this to the press…'”

The next day, it was leaked to the press.

“But all the ones with more than two brain cells were saying: ‘Hang on—does that mean the other six weren’t homeless?'”

Who is and who isn’t homeless matters, if you follow Ashley Sims’s logic because funding follows the need. Central government, charity, taxes, business rates—all pay into systems to help rid places like Torquay of their homelessness. All this, of course, is above and beyond basic dole and housing benefit, which—hypothetically, at least—should ensure there aren’t any homeless.

“But they don’t want that, do they? It’s a modern-day scam, what they’re doing […] TESH, the council initiative, was given £400,000 [$525,234] by the government. And guess what they did with that money—fuck me—they spent it on salaries. They employed 3.5 outreach workers that nobody has ever met. I went to TESH, I said: ‘What’s the names of these outreach workers?’ and they told me, ‘Oh, we can’t tell you that…'”

Ashley Sims scoffs when I tell him I’ll have to put his many allegations to his antagonists.

I contact Kath Frieldich, chair of People Against Torbay Homeless—which is a part of Sims’s despised TESH umbrella, though they are funded independently through private donations—and ask what they actually do.

“Basically, we have an outreach team that goes out 365 days a year. Posting signs are really important. We have strengthened that because we’re part of the TESH collective. The majority of the things we use day-to-day, they are things that are recyclable. We have our own food-bank. We also have what we call our moving-on bank…”

It’s hard to latch onto Frieldich’s sentences; her words move in vast flocks of newspeak that never breaks down into simple yes or no answers.

“Now, not to speak out of turn, but you need to think about where you’re getting your information about the £400,000 [$525,234]. I think you’re probably better off speaking to John Hamblin at [charity] Shekinah. If you go onto the TESH page, you’ll see the numbers are there. That’s pretty much public information—It’s nothing mysterious.”

I download Shekinah’s annual statements. They spent a million dollars in 2017, but that covers projects in other towns. In Torquay, they run something called Factory Row, a homelessness center with “13 full-time staff.” According to Companies House, the wages bill for Factory Row was £279,000 [$366,350] last year. I called Shekinah twice. They never returned my calls.

I try Frieldich again. “You don’t have any kind of estimate on the number of homeless? Would you say four is incredibly low? Is 28 a decent average?

“I’ll give you the same answer I give everybody: The figures—high levels, low levels—it doesn’t matter, it’s always too many.” She sighs. “I don’t know where this myth has come from that only people who sleep in doorways are homeless. There are homeless people all over. We’re very experienced with finding them. A lot of them won’t stay in store doorways. Who would, the level of attacks we get… Very nasty attacks, too.”

Where are the others?

“All over. Different places. I can’t divulge that. That’s a safeguarding issue.”

Who is safeguarding Ashley Sims these days? It’s just that he keeps walking into strange situations.

“Karma’s a beach” was The Sun‘s headline when they reported that Mr. Fake Homeless himself was now living in a trailer. His detractors savored the irony; it seemed that maybe he would finally learn his lesson. Sims tells it differently: His landlord gave notice that he wanted to sell the apartment he was living in.

But what of Karma’s a Beach, Part 2? Sims has shut down the entire brace of pubs, bars, and restaurants he owned in Torbay, the Devon borough that contains Torquay, and claims the council harassed him into it.

“When I had the pubs and the clubs, there was one where […] they said I wasn’t licensed for people to stand up. They had to sit down. They actually said, ‘If anyone’s playing pool, between shots, a member of staff has to tell them to sit down.'”

“When we applied to have the license changed, the woman from the council said: ‘We think Mr. Sims has got too much on […] because Mr. Sims and his partner have recently had a new child.’ I mean, can you imagine if they’d said that to a woman!”

“So, I got rid of all of them now; I’ve cashed all my chips in.”

Sounds bleak.

“Not really. I’m happier than I’ve ever been, to be honest. I’ve still got one business.”

Right. What’s that?

“It helps people with dementia to remember to eat and drink by playing music with subtle messages in it. We’re trying to get funding now.”

I’m not sure if that sounds like a business as much as a noble hobby. Regardless, why has Ashley Sims cashed in all of his chips? The pool table story is particularly weird—I’ve never heard of a “sitting license.”

I call Torbay Council. They ask me to email instead. I email, to tell them I’d like to talk to someone on the phone. They tell me to email anyway. I send over some questions. A response never comes.

Was it the final question that spooked them: “How many homeless people are there in Torquay?”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Gavin Haynes on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE UK.