The Former Home of Heroin Has Become a Luxury Rehab Hub

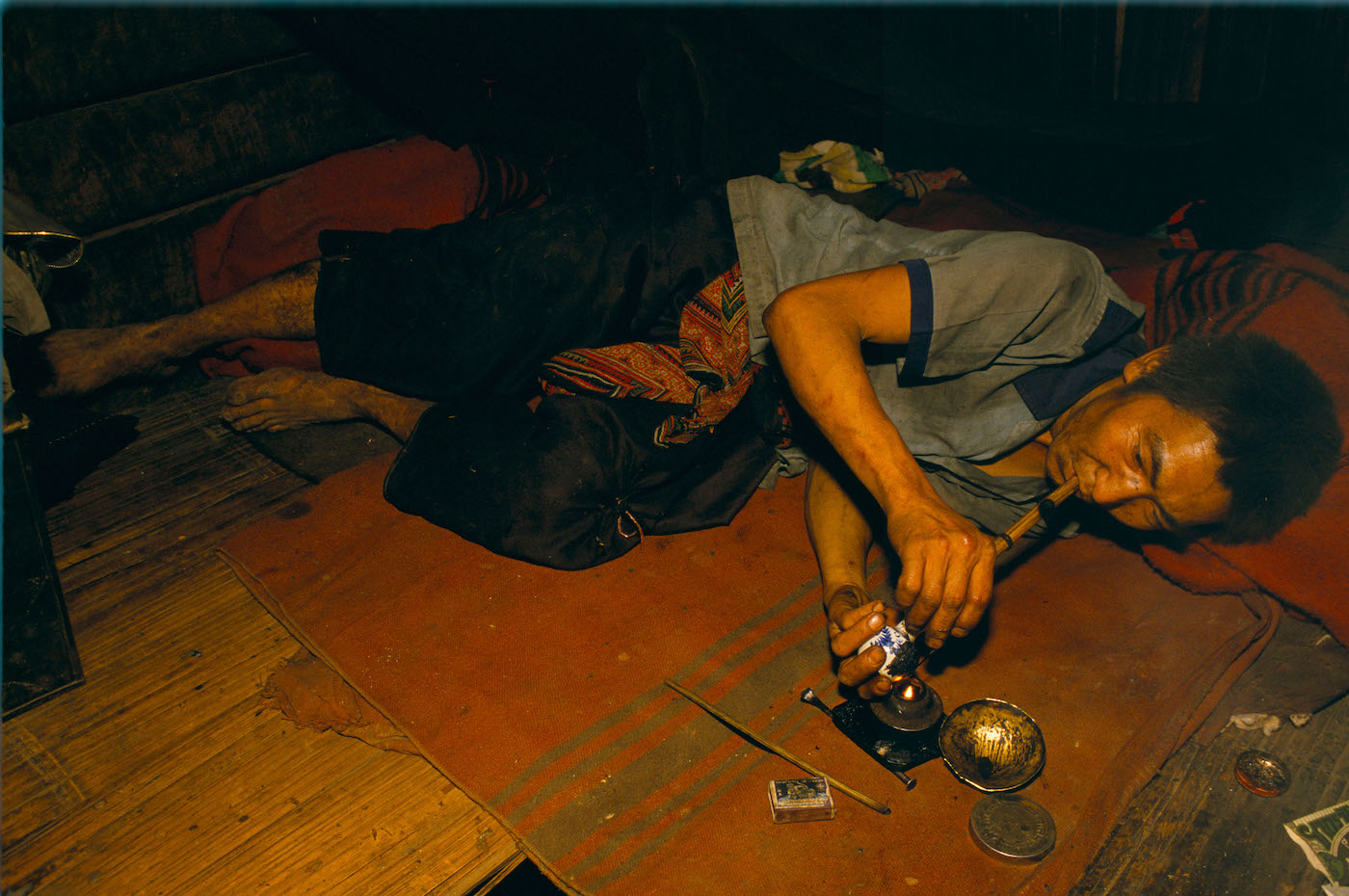

It was the gateway to one of the world’s largest opium trading routes, the place you came if you needed a hit: Chiang Mai, northern Thailand’s largest city.

Back in the 1950s, commercial production of opium in the region started to take off. China’s new communist government had banned the crop, and it didn’t take long for business to move south. Coupled with miles of inaccessible rugged hills and a cool climate, the Thai-Myanmar-Laos border – dubbed the Golden Triangle – became the ideal place to grow opium away from anti-drug law enforcement.

Aided in part by the CIA, who used the drug trade during the 1960s to fund their anti-communist Laotian allies, production seriously ramped up, and by the 1970s the region was producing more than 70 percent of the world’s opium.

Ironic, then, that this once debauched city has since picked up a PG reputation as Thailand’s premium rehab hub, with a number of clinics opening up in the last couple of years offering peace, wellness and serenity for suffering drug addicts.

Centres including the Dawn, Lanna Rehab, the Edge, Jintara and the Next Step now all operate in the area, and are a popular choice for patients from the UK with the resources needed to get themselves out there who are looking to get their lives back on track. These have joined Chiang Mai’s original rehab clinic, the Cabin – Southeast Asia’s answer to the Betty Ford Centre – which famously kicked out Libertines frontman Pete Doherty back in 2012.

But while they have helped the city to garner a new reputation, there’s no escaping its shady past.

“Chiang Mai was the place to come and get smack originally, many moons ago,” says Dylan Kerr a Birmingham-born counsellor, who works for the Dawn, one of the luxury clinics in the area. “A former Australian client of mine was part of a heroin cult here in the 70s. They called themselves the Orange People, and smuggled heroin from Chiang Mai [to Australia],” explains Kerr, before detailing some of the stranger stuff the cult was into: “They used to inject on the points of the cross: the stigmata. They believed that when Jesus was on the cross, the blood of Christ was heroin. So you’d invoke a religious experience from doing it.”

A lot of things have changed since then, of course, starting with Kerr’s former client, who chose to return to Chiang Mai – the place that fuelled his addiction – for treatment. Now in his sixties, the former Orange People member is clean and cult-free (Kerr was unable to confirm whether this cult was the infamous Rajneeshees of Netflix’s Wild Wild Country).

Chiang Mai, meanwhile, has been the focus of the Royal Project Foundation, which was set up in the late-60s to curb opium growing in the northern provinces. The Thai government also started to crack down on heroin trafficking routes after the launch of the 1984 nationwide opium eradication campaign.

By the 1990s, Thailand’s contribution towards the world’s heroin production dwindled, and though there are still areas in northern Thailand (including Chiang Mai) that grow the crop, the bulk of the Golden Triangle’s opium today comes out of Myanmar. Venture out into the hills, and many of northern Thailand’s former dope farms have been replaced by food crops, with a number of plaques in commemoration of the Royal Project dotted around to mark where the poppies once grew.

Down in Chiang Mai city, the general vibe is of health and wellbeing. Booze is banned during the day, there are an endless amount of ancient temples to visit, and worshipping monks are never too far away. Going cold turkey is never pleasant, but if you’re going to do it anywhere, there are worse places than modern-day Chiang Mai – which explains why new facilities, like the Dawn, are opening up.

These clinics are also much cheaper than your average western rehab. A 28-day programme at the Dawn, for example, will set you back around £8,500. Although certainly not cheap, this is less than half the price of similar luxury treatment centres in the UK or US.

Kerr suggests that being away from home also gives people the chance to reinvent themselves in a completely different environment.

“There’s a bit of an existential crisis when it comes to addiction,” he says. “It’s a case of people beginning to realise that this could be their destiny; to live like an addict, to live with all the trappings of having an addiction, which are pretty horrific. So that element of people getting out of their normal environment gives people a chance to really rebuild.”

The idyllic setting doesn’t work for everyone, of course, as Pete Doherty demonstrated back in 2012. Incidentally, Doherty returned to Thailand two years later, to the Hope Rehab clinic, just southeast of Bangkok, where Kerr actually started to work with the singer as his on-tour addiction counsellor – an “interesting” experience Kerr is pretty tight-lipped about.

However, he does say that the bizarre-sounding role of an on-tour addiction counsellor is pretty common these days, with plenty of other musicians taking counsellors on the road, adding that “there’s quite a lot of wising up to it now in the music industry”.

As for Chiang Mai, things have clearly shifted for the better: its drug-afflicted past a hazy memory.

This article originally appeared on VICE UK.