The Ex-Commando Who Reenacts His War on a Paintball Field

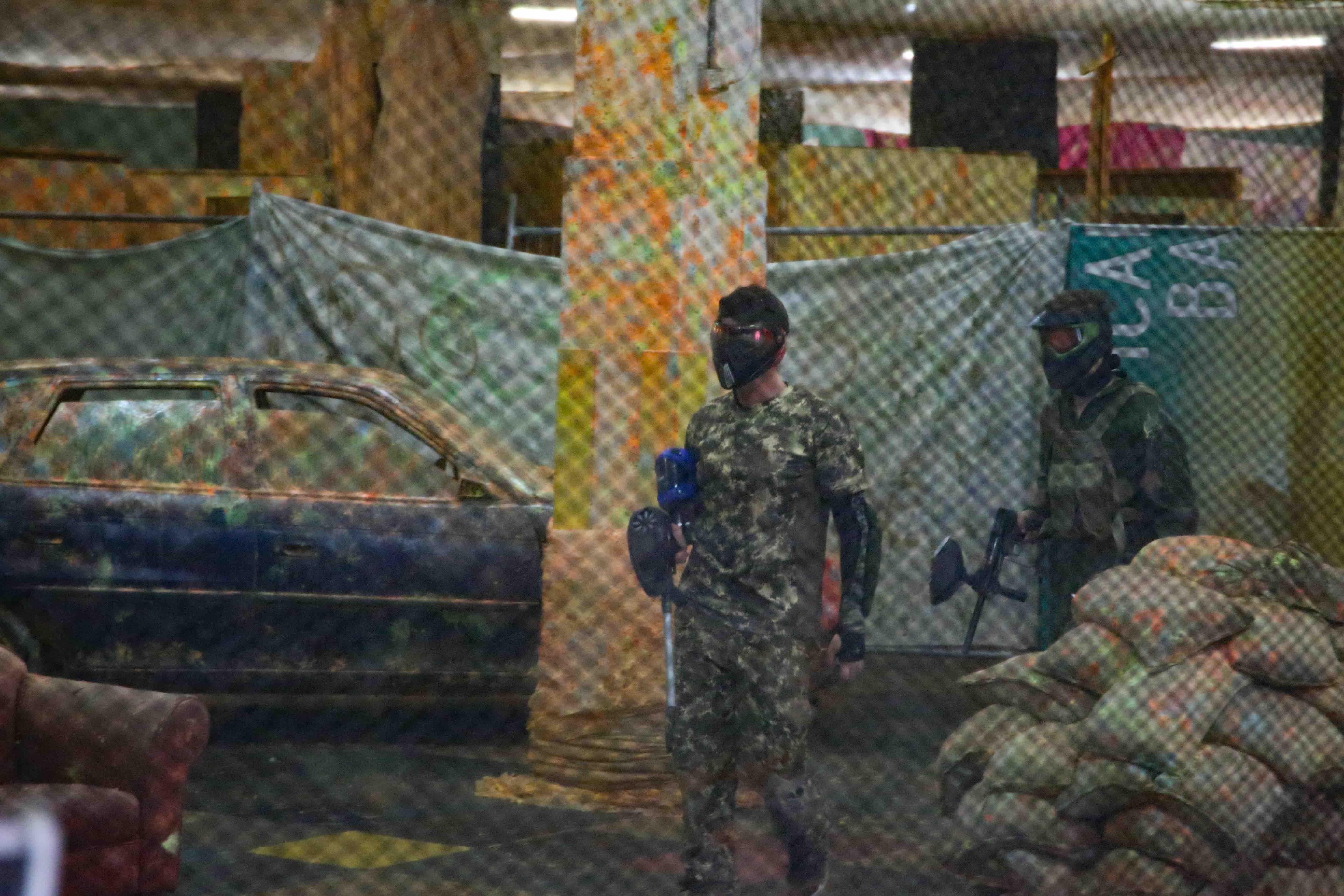

In an industrial complex tucked behind the Brisbane CBD, groups of staunch lads are silhouetted by the spotlight from their 4WDs. They pour steaming water into the barrels of their paintball rifles.

Francis, an ex-special forces Commando, has his arms comfortably crossed behind a chain-link fence, curtained in torn camouflage netting. He watches groups of young men approach tactical missions. Missions he designs in his specialist paintball facility.

Jacked on adrenaline, draped in military fatigues, balaclavas, and tactical vests, the boys are getting ready for the Combat Training games, orchestrated by Francis, who believes that paint balling should simulate cutting-edge tactical warfare.

Before he opened a Spec Ops training centre, Francis grew up in the quiet suburbs of Brisbane with five brothers and four sisters. “I was just one of those kids, loved the army and don’t have a crazy background story, ” he explained. “I came from a reasonable family, we had no dramas and good parenting.”

Francis served federally as part of the Counter Terrorism Tactical Assault Group, and was deployed in Afghanistan and Iraq with the Special Forces 2nd Commando Regiment, a unit that was exposed to more violence and casualties than any other arm of the Australian Defence Force.

When he discharged, Francis wanted to recreate a paintball centre that was inspired by his tours of combat. A theatre that would mimic his missions in Afghanistan and fuel his disfigured imagination.

“Through mucking around at paintball competitions. I realised these guys, the civilians, liked pretending to be army,” says Francis. “I knew that I could bring something new, bring it up to speed with modern warfare and create missions that essentially mimic what we did overseas.”

This is how Francis came to spend his days managing Spec Ops Paintball, a state of the art paintball facility frequented by military personnel, ex-special forces operators, video-game Rambos, and corporate thrill seekers. He essentially recreates the missions from his military career inside his paintball theatre, and watches civilians deconstruct his objectives from every possible direction, a method that helps suspend the horrific baggage of warfare.

“I didn’t find real combat that shocking because I mentally prepared myself for it. I ran through every scenario in my head. Including death,” says Francis. He doesn’t really speak unless spoken to, and he seems happy. He smiles a lot and greets his customers jovially before giving them advice on how to tackle their missions.

“You know I wrote a death letter? Explaining my will. I explained that this is what I wanted to do. This is why I’m doing it. It’s actually a pretty hard thing to do; writing your own death letter to your family and loved ones,” says Francis. It’s obvious that the young paintballers in the centre idolize him for his heroism and sacrifice, they stare with intrigue, as though being in his presence might encourage, in them, a die-hard will to survive

In the backroom, he has a micro-model of the paintball arena set on a table. There are whiteboards that participants can plan their attack on. Francis stands over the paintball field, playing God with the mock buildings, to ensure they fit the images in his head.

“The thing I think we [Special Forces] do really well, is mentally prepare you. Which is why we don’t have as many PTSD [Post-traumatic stress disorder] cases as the regular army does. I think it’s because we mentally prepare people all the way up through special forces selection.”

Before discharging, Francis worked as an assessor on special forces training camps, specialising in close quarter battle and shooting. “I’d get up and tell the recruits that this is the good side of war. I’ve come back from war. I haven’t been shot. I’ve got a wife and kids,” says Francis.

In his arena, he watched hordes of young wannabes spray each other with paint, a sore sight compared to the desperate young soldiers vying for his attention during the pre selection trials for the Special Forces.

“But then we will show them the bad side of what can happen, we might have another guy come out to tell them the truth and say, ‘you know what? I wish I didn’t go overseas,” Francis continues while sorting out tactical vests and helmets, “I lost my leg. I got blown up. My family left me. I’m on the pension. I can’t do anything. My life sucks.’”

Francis was able to prepare for the worst-case scenarios by imagining his missions the night before they were deployed into theatre. While the other soldiers caught up on sleep, Francis lay on his bunk examining every possible outcome.

Francis closes his eyes as he bobs his head around the imaginary warzone. “I’d run through scenarios in my head before bed. I would imagine the scenarios, if I get shot from that way, what am I going to do? I’m going to give fire back. I’m going to take cover behind that tree.”

In psychology, within the study of systematic desensitisation, this is referred to as “in vitro” exposure; where the subject imagines being exposed to their fears. The opposite, “in vivo” exposure, is when the subject is actually exposed to their fears, and in this case; deployed into combat.

“We lost three Commandos in a helicopter crash and an American pilot.” Francis struggles reconciling the role of a soldier with the death of friends. “All your down time really is; going back to base, identifying the bodies and doing the ramp ceremony. Taking them out and putting them on a plane. And then having to kick straight back into it.“

An ex-military medic who runs Miligear, a business that lends replica guns to film studios, unloads an assortment of Lithgow and M4 assault rifles that Francis used during his tours. The special forces are conducting interviews and will run through tactical maneuvers in the paintball centre. Francis gives the Commando’s feedback on their approach to his missions.

“I don’t think anyone in the Australian Defense Force has gone overseas and not come into contact with some form of IED [Improvised explosive device] within their platoon or company. So what we are going to do is have a team experience an IED strike. Explosions will be going off. And there will be smoke machines billowing out of the cars.”

According to the guidelines in Effective Treatments for PTSD, imaginal exposure is the most important therapeutic element of trauma treatment. In a study conducted by Mooli Lahad, researchers pointed out the similarities between the “as if” nature of creative imagination and imaginal exposure. Halfway between “in vivo” and “in vitro” exposure, the subject imagines the trauma scene but also represents it in physical or constructional behaviour.

“It will be the most realistic feel of war. I want to spotlight the field to give it a late afternoon or dawn attack atmosphere. We’ve got sight with the explosions, sense with the pain from the paintballs and smell from all the smoke, that’ll interrupt sight too. All to create the most realistic and fun game.”

Soldiers are constantly involved “in extremis” decision making and action. Their operations can involve intense emotions that might begin with notice of deployment, reactions during training, anticipation of operations, terrifying conditions during operations, and emotions following return from warfare.

“So, it’s sort of good being able to mentally prepare these guys by telling them what they are actually risking when they go to war. All the stuff that mentally touches you,” says Francis, “but I have to say it emotionally killed me. I don’t cry. Not much really worries me. My wife thinks I’m emotionally dead. If it’s no use worrying, what’s the point of crying?”

In the psychology textbook, Human Behavior in Military Contexts, researchers agree that, “emotion represents a universal and intrinsic aspect of human consciousness, which functions as an evaluative representation of the environment.”

I asked Francis if any amount of training could prepare soldiers for the horrific experiences that seem so natural to warfare, “I think training can prepare you for war. It can’t prepare you for the whole war scenario, because it’s not like you’re going to walk down the street in Australia and see dead bodies. Or if someone gets shot, trying to patch up your mate. It’s not like you can just simulate how that feels,” says Francis without any emotional cues. “But what you can prepare for is the gun fight. And that just comes from repetition.”

In Ian Langford’s manual, Australian Special Operations: Principles and Considerations, repetition is defined as, “the term used for practice and rehearsal. It is designed to reveal weaknesses in the operation prior to its execution.” However, the nature of combat against an enemy as unpredictable as the Taliban can never fully be rehearsed.

“We went to hit a [Taliban] stronghold. Our vision was limited. We had a bunch of casualties; guys on stretchers. Our interpreter Mo, an American citizen from Afghanistan, crossed the water and the Taliban set off an IED; a remote controlled bomb tied to three mortars,” says Francis, as though he is delivering a report.

“When it went off there wasn’t much left of Mo. All I remember was an explosion. I was three metres away from it. Body bits were flying everywhere.” Thinking about these scenes, is radically different to the weight of experiencing the explosive sounds, smell of blood and texture of flesh.

“When you’re going into contact you get an extra sense. You can feel what’s going on. Walking past someone in a village and they’re looking at you. You think are their faces covered? Are their rocks stacked up on the side of the road? Is the rock on top painted white? Have they got remote control IED’s?”

In Psychology, re-enactment of warfare is a form of dealing with trauma. The descriptions felt eerily familiar to the scenes Francis described surrounding the death of his interpreter, Mo. Francis’s concrete mental resistance regarding his deployment might be explained by his abstract, tactical wrestling with his past.

“We create the scenario based on what we’ve done overseas. We place rocks stacked up on the side of the road, and as soon as someone walks by we hit it with the iPad and it sounds off the explosions and smoke machines. Even the two safety operators on our fields are ex or currently serving military members. If a team is losing momentum, I’ll jump in there and reorganise things.”

Francis is the puppeteer of a theatre that stages his memories and imagination. He’s now planning to build missions that accommodate the dreams of soldiers. He has just finished building Osama Bin Laden’s fort in his centre.

“I always stick to real combat situations. I don’t make up my own. I’m going to be recreating Hitler’s bunker system within my field. A bunker where you will have to go through tunnels. A lot harder. A lot more tactical. Tight quarters. Very dark and very intense type of fighting but also very slow.”

Last week, Francis uploaded a photograph to his Instagram. He was sitting on the floor, in front of a whiteboard with his children in his arms. There were crude drawings of houses, stick figure men, a river and a bridge. The caption read, “when your father is an ex-commando and owns a paintball field… you spend your school holidays strategising how to escape a zombie attack!” We often neglect the emotional consequences of boredom and, as I flicked through Francis’ gallery, I wondered if war was, like life, the art of managing distractions?

For more, follow Mahmood on Twitter or Instagram

This article originally appeared on VICE AU.