The time Michael Jordan helped a guy win $1 million

RIGHT BEFORE HE HEAVED the million-dollar shot, the one that would launch an era of sports contests and change his life forever, Don Calhoun took a long look at his shoes.

He was only out here standing on the floor of Chicago Stadium on April 14, 1993, 15 feet from Michael Jordan and the Bulls, because of his shoes. “Those won’t scuff the court,” an arena worker said as she signed Calhoun up for a $1 million, three-quarter-court contest shot that the Bulls had been running every night.

As he stared at his feet, waiting to be told it was his turn to take the shot, he was warned, “Whatever you do, don’t step over the free throw line.” Calhoun, a 23-year-old office supply salesman from the Chicago area, darted his eyes from his non-scuffing sneakers to the free throw line about 80 feet from the hoop he needed to make.

The impossibility of the shot was settling in. He wasn’t going to be able to shoot it with both hands; he’d have to throw it like a quarterback. The Bulls had held the promotion 19 times that year already. Two people clunked the backboard. Another clanged the rim. The other 16 were air balls. Nobody came close. The best estimate of someone like Calhoun making that shot? Less than 1%.

But then, a calm came over him. He thought about his brother Clarence, who had told him five years earlier, just before he died, that Michael Jordan would soon be the best player in the NBA and the Bulls would be a dynasty. He thought about his bittersweet feelings toward the sport of basketball — he loved the game and was good at it, but he never made his high school team.

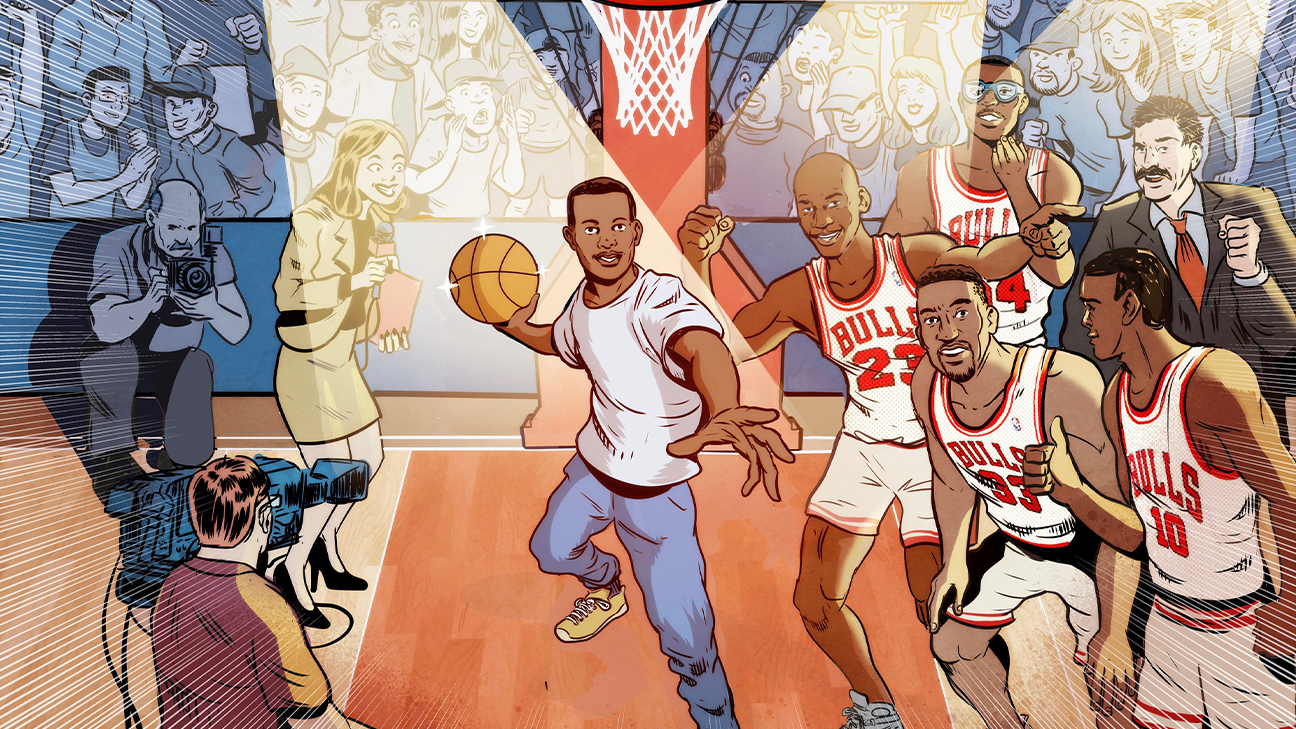

It might sound ridiculous, but as Calhoun stood there and heard his name announced, he became sure — 100% certain — that the shot was going to go in. The last thing he remembers is the steady hum of 18,600 people rising to cheer for him. As the Bulls huddled up nearby, Calhoun palmed the ball in one hand. The free throw line warning was bouncing around inside his head, and for a second, he felt his flow get disrupted.

But the flow came back as he stepped past the end line. He took one fast dribble, thought to himself, “This is for Clarence,” and then threw a high-arching rocket.

As the ball sailed toward the hoop, Calhoun’s eyes again turned toward his feet and he saw that he was very close to the free throw line — but a few inches behind. Whew. When he looked up again, he had a moment of panic. He’d thrown it too far and too hard.

“It looked like it was going to hit the shot clock,” he says.

But then the ball began to sink. It dropped, and dropped, and dropped, and… swish. Right through the net. Calhoun threw his arms toward the rafters, and the crowd let out one of those levels of cheers that aggravates the arena neighbors.

Then the real mayhem began.

The ensuing 30 seconds might be the most joyous footage of that Bulls team ever. Seriously, watch the most celebratory moments from “The Last Dance,” and compare those with the clips you will inevitably see this April 14 on social media on the 30th anniversary of Calhoun’s heave. John Paxson and Scott Williams go wild. Some player just off-camera slaps Calhoun’s ass over and over again, and even one of the game refs comes over, hits him on the back and hands him the ball from the shot. Phil Jackson stands there with an incredulous grin, looking like he just won the $1 million.

Suddenly, Calhoun found himself bumped and butt-slapped directly into the middle of the Bulls huddle, where the other players parted and there stood Scottie Pippen and Michael Jordan. Calhoun was the team’s 13th man at that moment. Calhoun was in there for a good 10 seconds when he felt Jordan slap him on the back and lean into his ear.

“Great shot, kid,” Jordan said.

Calhoun says he can still hear the way Jordan was yelling “Woo!” behind him the entire time. After the game, Michael Wilbon, then at The Washington Post, wrote, “Jordan, smiling in a child-like way I’ve never seen on the court, threw both arms around his neck and squeezed.” As the celebration exploded around him, Calhoun felt as if his life was going to change. He was the toast of Chicago for the next 24 hours, with the shot going viral by 1993 standards, with newscasts and newspapers all showing the clip so much that Calhoun’s shot is now referenced as the beginning of a boom in contests at sporting events. And best of all, Calhoun was about to become a millionaire.

Or so he thought.

BY THE TIME DON CALHOUN made his shot, in-game contests had begun to pop up here and there across the country. But Calhoun’s make caused an eruption in popularity. Chris Hamman, VP at industry leader SCA Promotions, thinks “The Calhoun Shot,” as it’s become known in the business, might have doubled or even tripled the number of contests.

“These types of contests grew quite a bit, and a lot of NBA teams started doing similar contests,” says Hamman, whose dad, Bob, founded SCA Promotions, which has been insuring sports contests since the mid-1980s. Chris compares Calhoun’s make with the impact Chris Moneymaker had on poker in 2003 when he went from an $86 online qualifier to winning the World Series of Poker (and $2.5 million).

The contests took off afterward. They were the perfect way to keep 15,000-plus people engaged during TV timeouts and between quarters. They were wildly popular crowd-pleasers back then, and remain slam dunk #ViralContent in the social media era. SCA Promotions has insured billions of dollars of sports contests since the mid-1980s, paying out something like $250 million in winnings over the years, according to Bob Hamman. (SCA was not the insurer of the Calhoun Shot).

As the Hammans note, the perfect contest is like the most tempting carnival game: just feasible enough to make people think they can do it while actually being extremely difficult. Everybody at the Bulls game that night in 1993 probably had sunk a long shot or two at some point in their life. In reality, Jordan himself might not have made one if you gave him 100 tries. “With the shot that Don Calhoun made, you could have Steph Curry out there and still make money,” Chris Hamman says.

But, as was the case with Calhoun, people do win enough to keep contest dreams alive. SCA Promotions insures more than $100 million in sports contests every year, and the Hammans love telling stories of paying off winners … because the vast majority of holes-in-one and half-court shots never happen. It’s a little like when sportsbooks leak out those betting slips of the fan who hit a 12-team parlay that cost $40 and pays out $250,000. The good news fuels the delusion of it happening to you.

One of the Hammans’ favorite winners was a Diamondbacks fan, Gylene Hoyle, who won a 1999 radio contest where she had to pick one Arizona player and an inning. If that player hit a home run in that exact inning during a specific game, she’d win $1 million.

Seems doable, right? The math is actually obscene. She picked Jay Bell, who was in the middle of a monster year (38 home runs and 112 RBIs). She had about a 1-in-2,916 chance. And yet, Bell came to the plate in the sixth inning with the bases loaded. He fouled off two straight two-strike pitches, then hit a home run on a pitch that could have been ball four. Afterward, he acknowledged that he knew about the contest and swung hoping to get someone $1 million. “That one stung,” Bob Hamman says.

The math on insuring high-stakes contests generally works the same way. Brokers come up with a likelihood that a random contestant could win — the Hammans say a three-quarter-court shot is less than 1%, for example — and divide it into the prize amount, then charge about twice that to insure it. For a $1 million contest with a 1% success rate, that means it’d cost the team $20,000 every time they run it.

Once the details are ironed out, insurance companies come up with all the fine print. Contestants usually must be randomly selected from the crowd. If it’s one shot, there’s no warmup toss or second attempt. If it’s three makes in 30 seconds, three makes in 30.1 seconds is close but no money. For something like a hockey shot that must go through a tiny plywood cutout and into a goal, the shot has to be entirely through. Not mostly through. Not on the line. Entirely through.

Insurance companies are unforgiving with teams that don’t explain the rules right, and it’s not unusual for franchises to end up paying out the contest themselves if there are any issues. The PR hit of stiffing a middle school geometry teacher out of $25,000 generally isn’t worth it.

But lawsuits and disagreements happen, and that’s what almost happened to Don Calhoun. One key stipulation in most insurance policies is that the contestant can’t have played an “organized” version of the sport in question for a certain time period before the contest — usually, five years.

Calhoun grew up in Chicago playing hoops on the playground with Clarence. Both had trouble making it onto junior high and varsity teams despite what seemed to be a worthy skill set. They were tough guards who loved dogging opposing ball handlers on defense. But they also played a brand of streetball that didn’t always translate well to high school hoops.

They certainly had talent, though. Clarence graduated and played at a junior college for his freshman year, then transferred to DePaul to walk onto the basketball team as a sophomore. Don, then a senior in high school, drew inspiration from Clarence’s unwillingness to quit basketball despite a high school career that didn’t pan out — he, too, planned to go to a small school to play hoops before transferring to a bigger school.

But one weekend, Clarence was on his way home from school to hang out with his family for a few days when the Calhouns got a dreaded phone call. He had gotten tired on the drive home, pulled over to rest, and been struck and killed by another car. He was 20.

Don was devastated. He didn’t graduate that spring on time as he grieved. But he went back to school in the fall and got his diploma. He slowly landed in a headspace where he wanted to use his brother’s memory as fuel. He bounced around at two community colleges and walked on with both basketball teams. One newspaper account from the time says he was 3-for-12 shooting in 11 career games.

But Don eventually walked away from school and from any formal basketball. He found out his longtime girlfriend was pregnant, so he got a job as an office supply salesman. Binders, notebooks, day planners, you name it, Don Calhoun was the guy to talk to. He was making a decent living, and he eventually had a son. The little boy’s name? Clarence Calhoun II.

When Clarence was 3, Don hugged him and told him to watch the Bulls game that night because Dad might be on TV. Clarence remembers his mom letting him stay up, although he’s not sure he saw the actual shot. He just recalls yelling and pointing at the screen as he watched his dad leap up and down with Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls. Then he went to bed.

Calhoun says that he marked on the forms that he had played some college basketball three years earlier and that the contest people shrugged about it. The insurance company disagreed, and the weekend after he had won, local news media began to report that Calhoun might not be getting the money. That prompted the Bulls to hold a news conference, where Calhoun sat beside Jerry Reinsdorf and several contest sponsors.

“It is unclear at this time whether the company that insured the event will pay on the policy,” a joint statement read. “However, regardless of its decision, [restaurant group] Lettuce Entertain You, Coca-Cola (Foundation) and the Chicago Bulls will honor the $1 million award and ensure that this event has a happy ending.”

Calhoun left that day knowing that the win was, in fact, going to be a win. He would immediately receive his first of 20 annual $50,000 payments. In the coming weeks, he appeared on “The Tonight Show with Jay Leno” and got a cup of coffee as a member of the Harlem Globetrotters. He was, unbelievably, the unofficial mayor of Chicago for a brief period. When Wilbon called Calhoun’s company for his story, someone answered by saying, “Reliable Office Superstore. This is the home of one-shot Don Calhoun, the million-dollar man.”

He never got many details about how the sponsors and insurance company worked it out. He just took yes as an answer. It wasn’t until a few weeks later that he found out that he might have needed a key assist from a secret source: Michael Jordan himself.

AFTER CALHOUN made the shot, he was asked to stay on the floor and do an endless string of TV hits and print interviews. As he bounced from camera setup to camera setup near the Chicago locker room, Bulls players kept leaving and spotting him on their way out. Almost every player came over, said congratulations and signed his basketball. “It took me three years to make a million dollars, and it took him five seconds,” Horace Grant joked afterward.

Calhoun got signatures from Grant, Scottie Pippen, John Paxson and B.J. Armstrong, plus two Heat players who swung by, Rony Seikaly and Steve Smith. And then, as he got ready to do another live hit, Calhoun saw Jordan and a Bulls staffer come out and stand nearby. Calhoun made eye contact with Jordan, who smiled back at him and was clearly there waiting to say hello to him. Calhoun wanted to run over and ditch whatever TV interview he was about to do, but producers kept telling him they were about to go live any second now.

When the lights went on, Calhoun did the best interview he could as he watched in dismay what was happening on the other side of the camera. Jordan said something to the Bulls staffer and left. Calhoun wasn’t going to meet MJ, after all, and it crushed him. The Bulls worker said he could leave the ball behind and they’d try to get Jordan to sign it.

But Calhoun had other plans. He didn’t want to leave the building without that ball, so he took it. He thought there was a chance he might run into Jordan somewhere down the road, then he could get an autograph.

Over the next few days, news broke all over the country that Calhoun’s winnings seemed to be in jeopardy. Calhoun clung to that ball, and it provided him hope. He had made the shot. The crowd had gone completely wild. The Bulls had pulled him into their huddle. He had left with the ball. That was all real, and he would have it forever. The $1 million? He sure hoped it was coming his way. But he also felt an odd peace about the money. The experience alone certainly wouldn’t pay for Clarence’s school clothes. But it wasn’t nothing, either. It was priceless.

As reports swirled, fan outrage was palpable in Chicago, which created enough heat on the franchise to figure out some way to pay the local office supply salesman his damn money. That led to the news conference and the first $50,000 check.

But what to do about his beloved basketball? The next school year, he had heard from a friend that Jordan always attended one of his kid’s home games at a specific school in the area. So he showed up that night — with his ball and two magazines — and tried to walk up to Jordan. The Bulls star had his own section away from the crowd, complete with security that kept people from doing exactly what Calhoun was trying to do.

Calhoun was stopped on his approach by a Jordan security guy, who said Jordan had a firm policy of no autographs at his kids’ events. Calhoun explained who he was and that Jordan had seemed to really want to meet him back in April. The security guy wouldn’t budge. “No autographs at his kids’ stuff,” the guy repeated.

But Calhoun had a funny feeling that he shouldn’t give up. He asked the security to pretty-pretty-pretty please tell Jordan that the guy who made The Calhoun Shot had come to the game hoping for his signature. The security guy shook his head. Calhoun was even willing to just hand the guy the ball to take to Jordan. No luck.

“Michael doesn’t do anything when he’s at one of his kid’s games,” Calhoun was told.

An unlikely thing happened near the end of the game, though. The security guard came to Calhoun in the stands and told him he could walk with Jordan to his car after the game. So Calhoun got his ball and Sharpie ready, then met up with the Jordan crew as he left the high school.

The first thing out of Jordan’s mouth? “Did you get your money?” Jordan asked.

Calhoun said yes, and Jordan told him something that caught him off guard. “We made them give it to you,” Jordan said. “We were upset that they were trying to not pay you.”

Calhoun was stunned. He had heard rumors that the Bulls players were agitated at the thought of him getting stiffed. But this was confirmation that Michael Jordan himself helped make him a millionaire. (Jordan declined an interview request for this story; the Bulls also passed on participating.)

As they got to a set of doors, Calhoun knew Jordan’s car was waiting for him on the other side. He asked whether Jordan would sign his ball, and MJ said no, that he had to stick to his principle of no autographs at his kids’ stuff. “Bring it down to my steakhouse and drop it off, then I’ll sign it,” he said.

Calhoun waved goodbye that night and thanked Jordan once more for advocating on his behalf. But as he left later, he felt a pang as he considered just pulling up to Jordan’s restaurant, dropping off the ball and hoping for the best.

The ball had grown to mean so much to him. It wasn’t the signatures, or that he thought the ball might be worth something like $20,000. Its actual worth was beyond what someone could pay. It represented the agony of losing Clarence and trying to carry his brother’s message with his own son. It represented the end of the bitter, unfulfilled taste that “organized” basketball had left in his mouth. It represented closing that chapter of his life when he had to fight and claw to pay every bill for his family, opening up 20 years where he knew he had a financial backstop each year.

Was he really going to hand the ball to some random steakhouse assistant manager and cross his fingers, hoping he’d see it again?

The answer was… yes, he was going to do exactly that. He felt as if Jordan’s signature was too important as the coda to the story of the ball. So he drove over there one day and implored the person he handed it to for help, saying that this ball meant so much to him, that MJ’s signature was the last missing component of an artifact from the most important moment of his life.

It must have worked. A few weeks later, he got a call to pick up the ball. “Michael signed it, and he wishes you well,” Calhoun was told.

The ball became a family heirloom over the next three decades. But not in the way you’d expect. Calhoun never locked it up in a vault or even put it in a protective case in the house. He left it in the basement of his house, and Clarence and Calhoun’s other three kids would dribble it and throw it around. He wanted his kids to be able to touch and feel something that had altered the trajectory of their family. “I’ll always keep it for you,” Don told Clarence.

For the next 20 years, Calhoun would get a check for $50,000 every year. Of that money, he’d have to set aside around $12,000 for taxes. He kept his office sales job for a few more years, and the other $38,000 (about $79,000 in 2023 dollars) was a very nice supplemental living. But, as Calhoun says, it was more like a bump up within the middle class. “In reality, you’re not rich,” he says. “You’re not a millionaire.”

Maybe he didn’t have generational wealth. But he was about to experience a generational breakthrough.

AS THE 30th ANNIVERSARY of the shot approaches, Calhoun takes a few weeks to decide whether he will talk about the shot, the money or any of it. He hasn’t done many interviews over the years. Eventually, he agreed to one but asked that his current location and occupation be left out of the story. Let’s say he’s living within a few hours of Chicago in the Midwest, and he works the second shift at a solid job.

He’s not hesitant because he’s a particularly shy person — once he gets rolling on the phone, he’s funny and unafraid to argue, and he comes off as very open and honest as he talks. Toward the end of an hourlong interview, he asks, “How can I get to the Hall of Fame?”

When the answer is a surprised chuckle, he says, “Don’t you laugh. I want to be in the Hall of Fame. I think I deserve it.”

He seems to be goofing around, but Calhoun changes lanes easily between being confident and reserved. He talks about the shot like he knew it was going in the entire time, yet it never sounds particularly braggy. He seems as if he had his 15 minutes and is content with that … but also thinks it’d be nice to have a small shrine to it.

Calhoun is 53 now. He catches the video only every few years, when somebody will show him a tweet or video link to a clip that you will most likely see every April 14 for the rest of eternity.

Calhoun is neither rich nor poor, at least in the traditional sense of the word. He does, however, feel wealthy when he talks about his four kids. The Calhoun Shot gave them all a better life. His youngest, Terrelle, is 20 and lives in Austin, Texas. Naomi, 22, is in nursing school. Gabriela, 28, is a teacher. And Clarence II, 33, is living out something beyond his own wildest dreams — and his dad’s.

Don Calhoun’s oldest son became a good prep basketball player at East Aurora High School and graduated in 2008. With five years of $50,000 checks left, Don encouraged Clarence to finish the job he and his brother had started years earlier: graduating from college. Clarence loved that idea. What a cool way to pay tribute to the uncle he never met but was named after. The problem was, he still didn’t know what he wanted to be when he grew up.

For the first few years after high school, he bounced between community colleges before getting into Wiley College, an HBCU in Marshall, Texas. He had developed an interest in the human body, especially biology. But college was no joke. Clarence Calhoun II limped to a 1.6 GPA in his first semester. It wasn’t that he couldn’t handle the coursework or the social life or the amount of work it took. It was the totality of doing all of those things all at once. He didn’t know a single person who had experience at this level of education. He was a rookie, surrounded by rookies.

That’s when he met a Ukrainian physician named Dr. Valentyn Siniak. Siniak was at Wiley teaching while he took mandatory tests to begin practicing medicine in the U.S. Calhoun was blown away by the level of support Siniak provided. Calhoun isn’t sure exactly what Siniak saw in him, but he saw something.

In emails to Calhoun, Siniak began calling him “Dr. Clarence Calhoun.” When Calhoun asked him for guidance on how he could get his grades up, Siniak made him laugh out loud. “I think you should start tutoring other students,” Siniak said.

“Tutoring?” Calhoun said. “I’m struggling to learn everything myself. How can I teach others?” Siniak thought this would give Calhoun an extra nudge to learn the material and boost his own command.

Siniak was exactly right. So right, in fact, that Calhoun sighs and shakes his head on a Zoom describing this section of his life. He still can’t fathom the way Siniak manifested belief into Calhoun’s life. His grades soared, and he liked working with other students. He had to work his ass off to get there — at one point, campus security officers would close up the science building for the night, knowing Calhoun was still in there. He’d study most of the night, inflate a mattress for a few hours and wake up the next day ready to do it again. “I found out I was smarter than I thought I was,” Calhoun says now.

And so in 2013, Calhoun graduated from college just as his dad’s $50,000 annual checks ended. He was the first in his family to get a college degree, and he battled and scrapped every day to get it.

He also had found out that his girlfriend was pregnant and that they were having a boy. When he told Don, he said, “Know what we’re going to name him, Dad?”

Don began to think about it for a second … and then it hit him. He didn’t say a word, and his son didn’t either. They laughed, hugged and celebrated the upcoming birth of Clarence Calhoun III.

Clarence Calhoun II started to chart a course for the next phase of his life, which had come into focus for him. “I want to be a doctor,” he told his dad, and he began to try to get into medical school. He worked jobs at Jiffy Lube, a toxicology lab and other places before he finally passed his labs and got accepted. This was happening. Not only was a Calhoun going to earn his degree but he felt as if he might actually become the Dr. Clarence Calhoun his instructor, Dr. Siniak, had predicted in his emails.

That’s why it breaks the younger Calhoun’s heart to tell this next part of the story. Siniak didn’t get to see Calhoun get his degree. In January 2013, Siniak was struck and killed while riding a motorcycle in Texas. “Having him believe in me helped me believe in myself,” Calhoun says. “My biggest downfall that was keeping me from excelling was my confidence. I just didn’t think I could. I didn’t have anybody around me who had done it.”

Over the next eight years, he passed his boards and did his residency, and an envelope arrived in May 2021 that he couldn’t wait to open. The piece of paper inside made it official: He was now Dr. Clarence Calhoun.

He went to his dad’s house to show him in person, and they had a long embrace. Don couldn’t stop smiling. After a minute, he walked out of the room and came back holding two things he was giving to his son.

One was the shoes he had worn during The Calhoun Shot. Clarence noticed they had a signature on them. They were autographed by … none other than Don Calhoun, which makes Clarence laugh to this day when he holds them up. His dad can be a goofball — an inspiring goofball. “He drops spiritual motivation all the time, and that’s always needed,” Clarence says. “In moments when it feels like life is too difficult, he helps you figure out how you can do it.”

For the second item, Don Calhoun didn’t hand it to him. He reared back and threw a push pass at his son’s chest.

“Here, I want you to have this,” and he chucked an old basketball at his son. Clarence Calhoun II hadn’t seen the ball from The Calhoun Shot in 10-15 years, and now it was going to live with him and his son. The two older Calhouns, Don and Clarence, hugged once more. And as Dr. Clarence Calhoun left that day, with a basketball under one arm and some old shoes under the other, his whole life felt like sinking a less than 1% three-quarter-court shot.