27 years ago, Phil Hopkins fell short against No. 1 Purdue

Fairleigh Dickinson coach Tobin Anderson talks about the Knights’ stunning upset of Purdue and what they need to do to reach the Sweet 16. (2:01)

Fairleigh Dickinson will live now in NCAA tournament perpetuity, intertwined in highlight reels and slow-motion montages that provide eternal March backdrops.

The Knights harassed and hounded No. 1 Purdue to become just the second men’s No. 16 seed since the NCAA tournament expanded to 64 teams in 1985 to pull off a first-round upset. No. 16 seeds are now 2-150 vs. No. 1 seeds after the 63-58 win.

As history unfolded Friday night for Tobin Anderson’s team, I couldn’t help thinking of the coach of one of those forgotten 150. His funeral is Saturday morning.

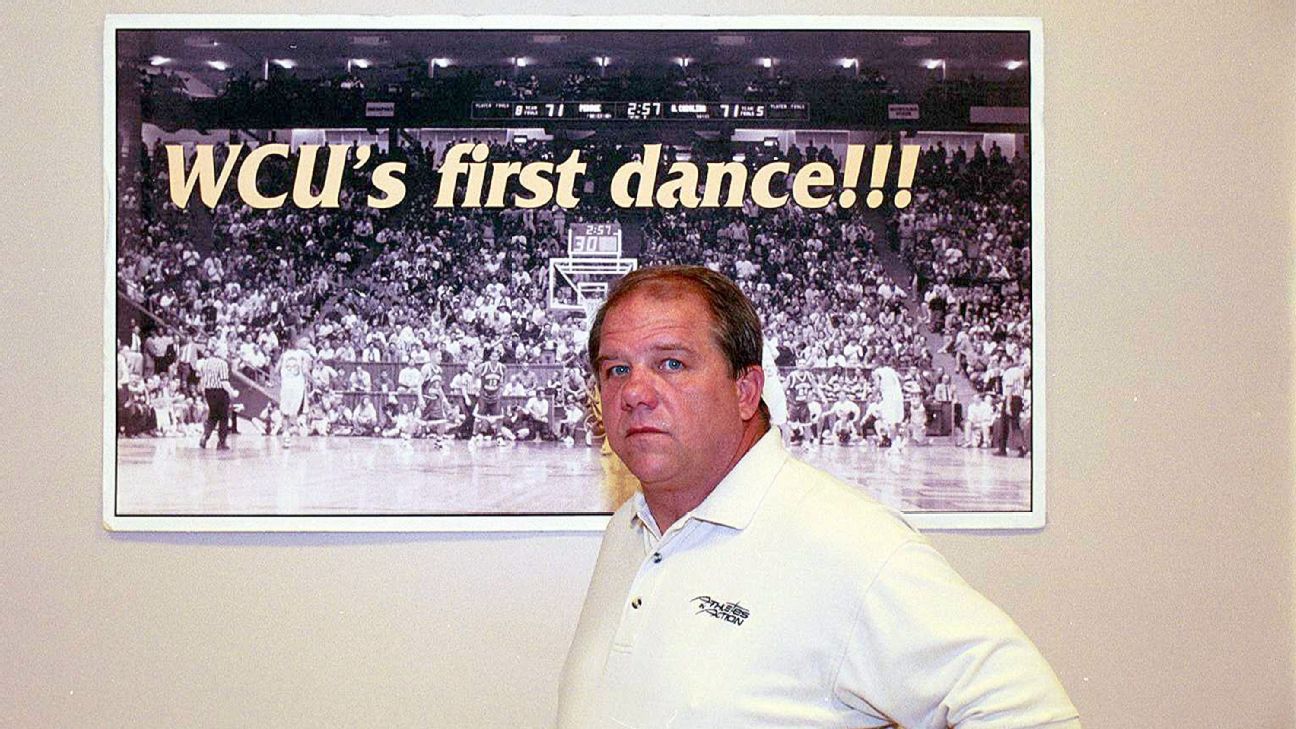

I wished I could have texted former Western Carolina coach Phil Hopkins on Friday night, a coach who will be remembered for being almost famous. After nearly pulling off one of the great upsets in NCAA tournament history as a No. 16 seed back in 1996 against No. 1 Purdue, Hopkins’ story reminds us that history doesn’t remember the near upset.

Phil Hopkins died on March 2 at age 73, and his services are on Saturday morning in his hometown Pelzer S.C. Having gotten to know Hopkins in the years after his Western Carolina tenure ended up as the archetype for March heartbreak, it’s safe to say his affinity for rooting for the underdog would stay strong in the afterlife.

With Purdue again on the cusp of infamy on Friday night, it was hard not to think about Hopkins. It was Gene Keady’s team back in 1996 that got scared to the brink, as Western Carolina’s upset bid rocked the The Pit in Albuquerque to unmatched decibels. Hopkins’ plucky Western Carolina of the Southern Conference had two shots in the air in the final seconds — one to win and one to tie — that rimmed out. Purdue survived and advanced, 73-71.

Butler coach Thad Matta, who was Hopkins’ top assistant on that 1996 Western Carolina team, once told me: “I don’t know a day goes by where I don’t think about missing those two shots at the end.”

The homespun Hopkins and the Catamounts of Cullowhee, S.C., were relegated with those final caroms from tournament icons to footnotes. Instead of being the standard bearer for NCAA upsets, Hopkins and his crew were instead forever tied to what could have been. “We deserved to win,” Hopkins said in the press conference that night back in 1996.

Hopkins seized the NCAA tournament moment. After upsetting Davidson in the Southern Conference title game, he proposed to his then-girlfriend on the arena loudspeaker. He got a lot of mileage out of the line quantifying his excitement: “Well, I’ve been married before, but I’ve never been to the NCAA’s.”

Hopkins’ career profiles as a classic multi-directional school vagabond — Middle Tennessee, Radford, Wyoming, Indiana State and finally getting his break when promoted at Western Carolina. He made the NCAAs in his first season as head coach at Western Carolina, but never quite recaptured the magic.

Once Hopkins’ moment slipped away, his college career soon followed. He coached at Western Carolina four more years before a new athletic director — current ECU AD Jeff Compher — didn’t renew his contract. The school hasn’t returned to the NCAA tournament since that night in 1996.

I stumbled across Hopkins’ story early in my career, researching a Georgetown star named Lee Scruggs who had once committed to Western Carolina before going to junior college and ending up at Georgetown.

In trying to track down Hopkins to inquire about Scruggs’ high school recruitment, I happened to catch him on the phone in the break room at a junior high school in Walhalla, S.C. It was an unlikely start to a friendship. And the setting was the essence of a coach who found more satisfaction coaching far from the bright lights.

A few years later, with his former assistant Matta on the cusp of taking Ohio State to the NCAA tournament as a No. 1 seed in 2007, I went down and spent some time with Hopkins in Walhalla. He took me to a cafeteria-style fried chicken joint in town and gleefully detailed what amounted to the coaching equivalent of a country music song.

While at Western Carolina in the wake of their early success, a few colleges called about him getting bigger jobs. But he stuck around out of loyalty and fit. But things soon unraveled. He ended up getting divorced from the woman whom he proposed to over the arena intercom. Even the swoosh tattoo he got after getting the Western Carolina job backfired, as Nike ended its contract with Western not long after it made the NCAA.

Perhaps the most gutting professional thing that happened to Hopkins was that his athletic director didn’t realize that he was sitting on a goldmine roster. Hopkins didn’t get brought back after going 14-14 in 1999-00 with star freshman twins — one was the league’s Player of the Year, the other was the league’s Freshman of the Year.

After Hopkins’ departure, Jarvis and Jonas Hayes transferred to Georgia, with Jarvis Hayes developing into the No. 10 pick in the NBA Draft in 2003. By then, Hopkins was coaching in junior high and found that same question lingering from the Purdue game — what could have been?

While things turned sour professionally for Hopkins in college basketball, one of the reasons our friendship endured long after our fried chicken dinner in 2007 was that he never let the moment define him.

He found a niche coaching junior high kids, and even turned down a Division II job because he liked coaching junior high boys and girls. As he spun the stories at dinner at the Steak House that night, players and former players came up and greeted him like family. He’d run for mayor in town and lost in a buzzer beater of an election, but it was hard to see how.

“He was one of the most unselfish people I’d ever been around,” said Eastern Illinois associate head coach Doug Novsek. “He was humble and loved his family.”

Hopkins bragged on his two kids, Phil Jr. and Somer, and sent picture after picture of him with his seven grandkids. They didn’t know him as an almost famous college coach, but a beloved grandpa everyone called Hoppa.

One of the enduring powers of the NCAA tournament is how it bonds us all. Every March, it reunites alumni, ignites camaraderie through brackets and fuels group texts from old friends. It’s a flurry of games, all condensed as the years pass to select moments that transcend and resonate.

Hopkins’ moment rimmed out, but it never rattled his spirit. He’d check in every March with an update for what he liked to call his 15 minutes of fame, detailing the interview requests and folks who’d check in. But most of our texts are the pictures of him and his grandkids, who he coached with palpable pride after moving to Richmond in recent years.

The night that Hopkins’ relevance for being almost famous gave way to UMBC’s Ryan Odom capturing the holy grail of upsets back in 2018, I shot Hopkins a text to see if he was watching. The exchange perfectly summed up his life after college basketball when he wrote back the next day. Hopkins admitted he slept through the famous UVA-UMBC game, as he was worn down from spending the morning with the seven grandkids.

“I promise that no one at UMBC,” he said in his text back in 2018, “had as much fun as I had this morning.”

Phil Hopkins will be remembered as the man for whom the epic upset eluded. As he’s laid to rest on Saturday morning, I’ll remember my friend as someone who still found all the shining moments.