Ian Mulgrew: Marathon medicare trial finally ends

Credit to Author: Ian Mulgrew| Date: Sat, 29 Feb 2020 01:43:29 +0000

The interminable constitutional trial over the provision of private health care in B.C. — dubbed The Flying Dutchman of the B.C. Supreme Court by lawyers — finally made it back to harbour Friday.

In many ways, what should have been an intellectual cruise involving a few months of written argument and data from the medical system became a veritable Royal Commission that has generated a library of evidence. It involved 194 days of proceedings over 3 1/2 years that mocked timely justice and badly bruised the belief that the courts can act as an effective brake on bad government by providing a remedy to unconstitutional law-making.

The length of time and cost of the case are an argument that the courts are no longer capable of efficiently resolving such thorny questions of social policy.

As intervener lawyer Joseph Arvay said: “This case would appear to be, at least in my experience, the most complex Charter case I’ve ever seen. And one that truly does test the institutional competence of the court.”

At a time when more and more Canadians think the country isn’t working, the dysfunctional legal system must be considered a primary reason. Indigenous people have run into the same problem trying to hold governments to account through litigation — they too have found themselves bogged down in endless process that pours millions-of-dollars into lawyers’ pockets.

The duration brought its own risks and demands on memory — the constitutional challenge of two provisions of the Medicare Protection Act was nearly derailed late last year when B.C. Supreme Court Justice John Steeves required health care. This week Steeves couldn’t remember what prevented the government from enforcing the law.

“There is in place a consent order allowing private surgical services to continue,” plaintiffs’ lawyer, Robert Grant, explained — issued by Justice Janet Winteringham following an injunction she granted in November 2018 after Victoria amended the law and planned enforcement, though its validity was in question.

“Did I sign that (order)?” the justice asked.

“No, it carries on from Justice Winteringham,” Grant replied.

“So, it has to do with the amendments, as I say, that occurred during my trial,” Steeves said.

“Exactly,” Grant said. “And what it did is effectively to confirm they won’t be employed until your lordship ruled, so that allowed the status quo to continue.”

“Maybe (government lawyer Jonathan) Penner can give the minister my compliments for making my job easier,” the justice quipped.

Two private clinics and a handful of patients launched the litigation roughly a decade ago because the constraints on dual practice by doctors and private health insurance would force private clinics and diagnostic centres across the province to close. No evidence or data was offered by either government to support the assertion that the private clinics cause harm to the public system and B.C. has not measured the impact or effect of the clinics that have existed for a generation.

“They would have welcomed an opportunity for an impartial objective empirical study,” Grant said. “It might have made this litigation unnecessary as it would have confirmed that private surgeries did not have any adverse effects on public surgeries.”

The Vancouver lawyer accused the government of grossly mischaracterizing and misrepresenting evidence in closing statements he said were little more than fearmongering. He pointed out B.C. has had de facto private health care for 20 years and the sky hasn’t fallen.

To end that status quo, he added, would make the public health system even more overcrowded as the 65,000 private surgeries done annually join already historically long waiting lists.

“Nobody gets ahead in the public queue by having private surgery,” Grant explained. “What happens is you leave the queue. You’re not jumping the queue, you’re leaving the queue.”

Instead of relevant data, the federal and provincial governments resorted to fervid rhetoric about the prospect of U.S.-style health care and the poor languishing in dirty beds at the mercy of greedy, unscrupulous physicians. At one point they accused a respected neurosurgeon of having “scaled back public work because he wanted more time to smell the roses and read a book.”

“This is an egregious mischaracterization of the evidence,” Grant told Steeves. “In fact (the doctor) suffered a family tragedy. His wife developed terminal cancer — and he needed to scale back his public on-call commitments as he couldn’t be operating all night due to his family’s needs … With his wife’s illness and passing, he could not do this with four children.”

Grant swept the broader accusations aside too:

“If there was one shred of evidence that doctors practising in the private system, just one piece, one example of a doctor performing private pay surgery, shirking a commitment to the public system or causing any problem at all for the public system, we can be certain they would have called that evidence, but they didn’t.”

He urged Steeves to draw an adverse inference from the government’s failure to call a single doctor or senior administrator to give evidence about problems the public system had experienced as a result of private surgeries.

“The evidence in this trial shows thousands of British Columbians wait too long past government-mandated medically maximum acceptable waits for their condition, risking progression of disease and in some cases shortened lifespan or death,” Grant concluded. “In evidence in this trial, is the fact that in one year, in just one health region in B.C., Fraser Health, 308 patients died waiting for medically necessary surgery. B.C. patients need a ‘safety valve’.”

Before the courtroom emptied, Steeves said: “I’m looking forward to completing my judgment and setting my name on it, and, once I’ve done that, I’ll join the rest of the world watching the progress of this case with great interest.”

He is expected to take several months, perhaps longer, on his ruling. Appeals are expected to follow, which means a final decision could be two, three or more years away.

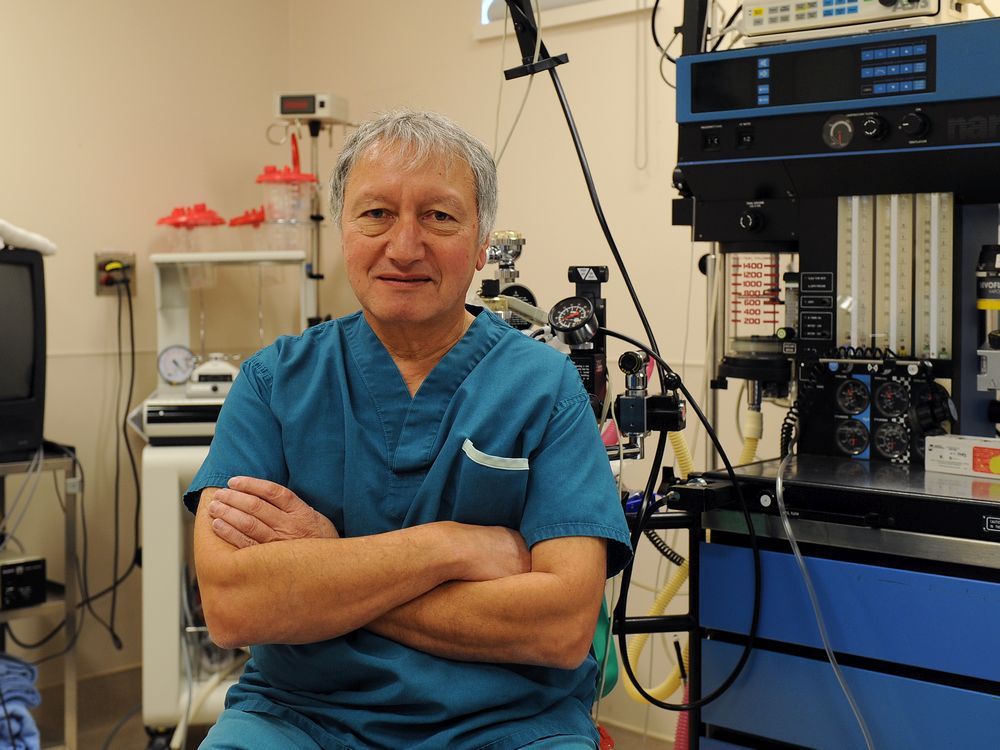

Outside of court, Dr. Brian Day, the face of the litigation, said he was relieved that the trial was over.

“Suffering patients — the more than 30,000 a year who wait past the government’s own maximum acceptable wait times, and the 18-a-week who die on public wait lists in B.C. — need the justice system to rescue themselves from their plight,” he said. “It’s astonishing that we are the only country on earth that outlaws private health insurance.”