A Vending Machine in Canada Is Dispensing a Drug Twice as Strong as Heroin

Credit to Author: Maia Szalavitz| Date: Mon, 10 Feb 2020 15:07:18 +0000

When he heard about Mark Tyndall’s plan to offer the opioid hydromorphone to people with addictions via a vending machine, Henry Fester wanted in.

Sold under the brand name Dilaudid, hydromorphone is best known in popular culture as the drug most prized by pharmacy robbers in the 1989 Gus Van Sant film, Drugstore Cowboy. It’s sometimes called “dilly” on the street; it’s around twice as strong as heroin.

Fester, a 62-year-old former Canadian television director, had been addicted to opioids for 30 years. He’d started with pain treatment, but then began buying drugs illegally. Now living in Vancouver’s fentanyl-infested Downtown Eastside, he wanted to protect himself—but he was not ready to quit and had not found methadone or other medications for opioid use disorder helpful.

Fester has already lost eight close friends to overdose. He has even saved one of his own family members by doing CPR until an ambulance arrived—and he himself has also overdosed and needed to be revived with the antidote, naloxone, on more than one occasion.

“I was always interested in a clean supply and not having to worry about dying just to try to keep pain-free and to keep well,” he said.

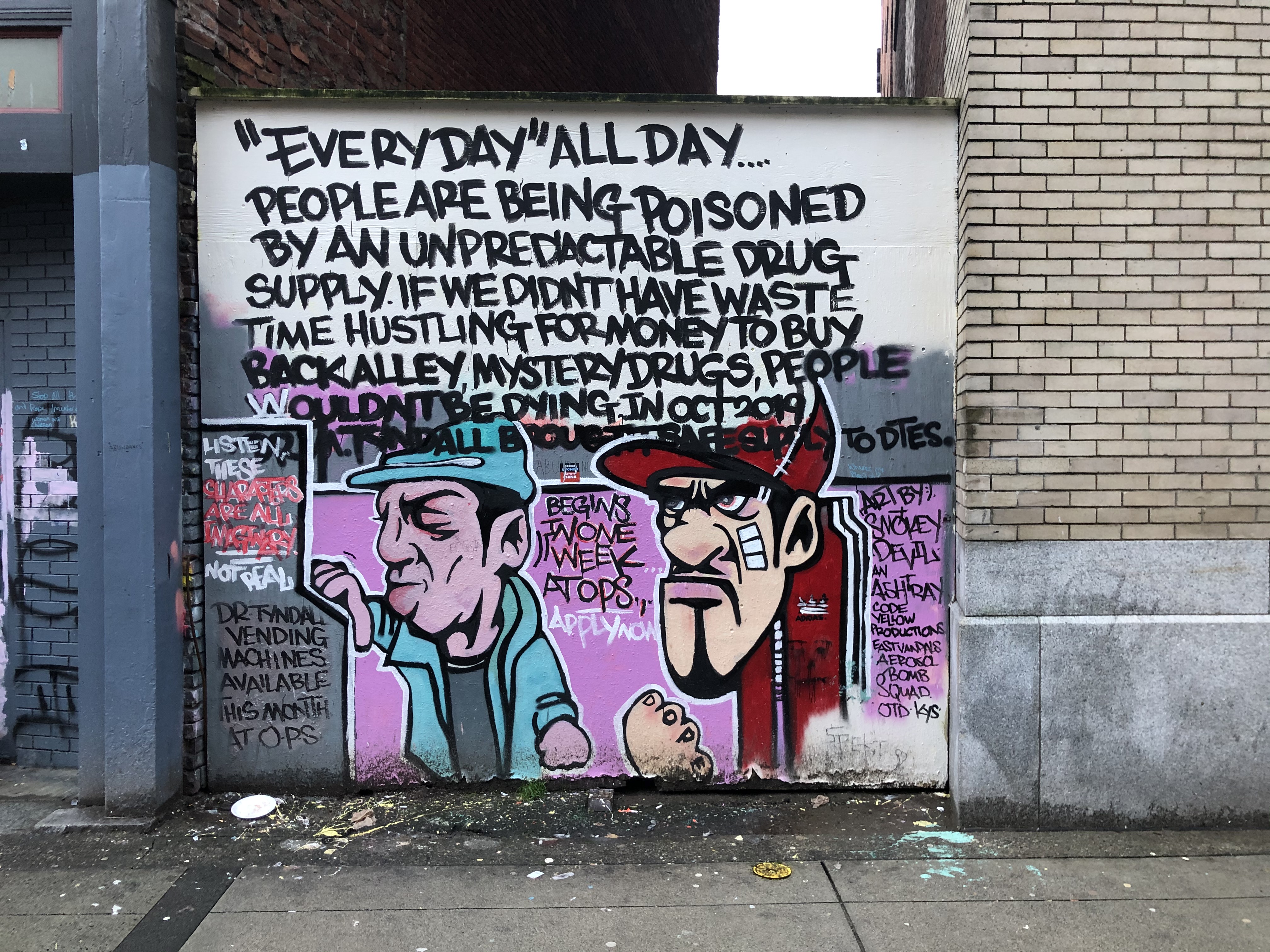

Tyndall, a professor of epidemiology at the University of British Columbia, originally proposed the idea half-jokingly at a conference two years ago when discussing the overdose crisis. The media jumped on it, he said, and “by the end of all the interviews I gave, I came to the conclusion this was the greatest idea I've ever had.”

The vending machine began dispensing in January. Fester visits it to pick up his medication four times a day.

“It's eliminated a huge chunk of my depression and my anxiety, and it's given me a reason to continue on each and every day outside of my addiction,” Fester said, describing the relief he felt at not having to chase down dealers or worry about arrest or overdose. He added, “I feel like a normal person again. It's only been two weeks, but it's made a huge difference to my life.”

The idea of providing potentially deadly opioids to addicted people via a vending machine might sound actively counterproductive on its face. But with a heroin supply full of fentanyl, Tyndall argues, providing a safer supply to people who can’t or won’t quit just makes sense.

He notes that the province of British Columbia, where Vancouver is located, already has 30 overdose prevention sites, where people can inject drugs under medical supervision and be revived if they overdose. These sites significantly reduce the risk of death where they are located and help get people into treatment—and no one has ever died at one, anywhere.

But, Tyndall asks, why wait to reverse overdoses of poisoned street drugs? Why not just provide a safer supply of drugs of a known dose and purity and prevent them entirely? And how many barriers put up by the medical establishment to protect people are really harming them by driving them away from care?

Vancouver also has a small program that provides either pharmaceutical heroin or Dilaudid to people who have not been successful with methadone or buprenorphine. The Providence Cross Town Clinic enrolls fewer than 200 patients, however—and in order to participate, they must use the injectable drugs on the premises, which requires that they visit more than once a day at specific, assigned times. Some doctors also simply prescribe Dilaudid to people with addiction—but they are few and far between.

Research has shown that even strictly limited heroin and Dilaudid treatments like that at Cross Town reduce street drug use, improve functioning and may reduce mortality. They do not deter—and may even encourage—abstinence in the long run.

While acknowledging this good work, Tyndall argues that many more lives could be saved if there were fewer requirements and less hassle involved in getting a safer supply.

Right now, the vending machine is more a proof of concept than anything else. Thirteen patients are currently enrolled and a total of 48 can be served by the machine on any given day. To participate, they must first be medically examined and have their urine tested once a week to measure any outside drug use. They also must have a recent history of overdose and unsuccessful prior attempts at treatment. But participants do not have to attend counseling, swear off all other substances or show up every day at a particular time.

The machine is located inside a building next to one of Vancouver’s overdose prevention sites, although participants are not required to use it when they take their drugs. Custom built by a company that contacted Tyndall when they heard about his idea, the MySafe machine looks like an ATM and is stocked with doses that are individually determined by Tyndall and the patient and obtained from a pharmacy.

Access is biometric: people are identified by a scan of the pattern of veins in their hand. The machine asks them a few questions about how they are feeling and dispenses the drug once they’ve been identified by placing their hand on the screen. Users can access it up to four times a day—with two hours between any given dose—and receive up to a total of 16 eight-milligram pills. They can either take them orally or, as most prefer to do, inject them.

The machine weighs 800 pounds and the total amount of drugs it contains is small. This makes theft or hacking attempts unlikely: for the same amount of effort and risk, the average drug store would be a far richer target.

Figuring out the right balance between access to the drugs addicted people want and protection from the risks of those drugs is one of the key tasks for sane drug policy. Tyndall’s machine is one approach—by allowing people to choose when they get their drugs and where they use them, it could offer a more scalable model with less supervision than current prescribing methods.

It may also provide a hidden benefit: the two-hour window between doses and the four times a day limit may help people better time and control their use.

Michael Farrell, director of the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, has studied opioid addiction prescribing issues for decades in both Australia and the U.K. In Great Britain, doctors were allowed to prescribe heroin and other opioids to people with addiction with few limits between the 1920s and the early 1970s, an approach known as the “British system.”

Patients basically picked up the doses that they wanted once a week or so, along with needles. Some could even get pharmaceutical cocaine as well. (British doctors can still actually prescribe both drugs, but only at certain clinics and with more strings attached; earlier patients were grandfathered in).

“I prescribed heroin that way for nearly 20 years,” said Farrell, noting that he has mixed feelings about the system because it wasn't clear that it reduced harm. “I had a few people who unquestionably benefitted from such a lax regime,” he added.

But a study of 128 British heroin patients who started in 1969 and were followed for 22 years found that 34 percent had died, a shocking mortality rate that is not clearly better than that found in the U.S., which does not offer heroin prescribing (one American study simply followed people with heroin addiction who’d been forced into treatment and then released—and it found a 39 percent death rate after around 20 years). It’s important to note, though, that if this prescribing had occurred in the context of a fentanyl epidemic, the mortality rate for those who received prescribed heroin would undoubtedly be lower than that for those who continued using the street drug because street fentanyl is more deadly.

The real issue, Farrell said, is that controversial treatments like today’s strictly controlled heroin and Dilaudid prescribing—and even methadone and buprenorphine—are not more widely available. While the U.K., the Netherlands, Switzerland, Denmark, Luxembourg and Germany all have heroin programs, they remain small and the level of medical supervision is both intensive and expensive. “The problem is that it does not get scaled up or translated into scalable practice. I suspect that this new dispensing approach is a way to try and address this. The evaluation of it is critical,” he said.

Tyndall is planning to study the outcomes for people using the machine, but a huge part of the reason he installed it is that he is just tired of watching people die preventable deaths.

“I'm trying to make the case,” he said, noting that bureaucratic obstacles prevented him from using a $1.4 million Canadian grant that he’d received to expand Dilaudid treatment via more typical prescribing when he was head of the British Columbia Center for Disease Control. “It was just so frustrating…Nobody said no, but nobody said yes.”

He added, “This is a response to a poisoning epidemic and people deserve access to something that won't kill them.”

Meanwhile, Fester is hoping to use the machine to allow him to go back to work or at least be of service to others in the time he no longer has to spend chasing heroin. He said he wants “To get my life back in order, to a point that I can feel proud of myself and not feel like I'm less than human.”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Maia Szalavitz on Twitter .

This article originally appeared on VICE US.