How Ring Went From ‘Shark Tank’ Reject to America’s Scariest Surveillance Company

Credit to Author: Caroline Haskins| Date: Tue, 03 Dec 2019 16:13:09 +0000

This is the first of a three-part series, where we’ll explore how Ring transformed from start-up pitch to the technology powering Amazon's privatized surveillance network throughout the United States.

When Ring came to Baltimore, residents believed they were out of options.

Pastor Troy Randall, who lives in northwest Baltimore, said that his neighborhood has been “held hostage” by drug sales and associated violence. Many people want to move, he said, but don’t have enough money, while older residents can’t move to a new place. People are trapped.

“The police are not doing anything,” he said. “They are not getting out of the cars. They're not walking the beat. They allow the guys to continue to sit around and to sell drugs.”

Many residents don’t trust the Baltimore police at all, and for good reason. A 2016 Department of Justice report found that the Baltimore Police Department systematically targets people of color in the city. Compared to white residents, people of color are disproportionately stopped, searched, arrested, and subject to violent and excessive force. They’re also at a disproportionately high risk of being killed by police.

Enter Ring.

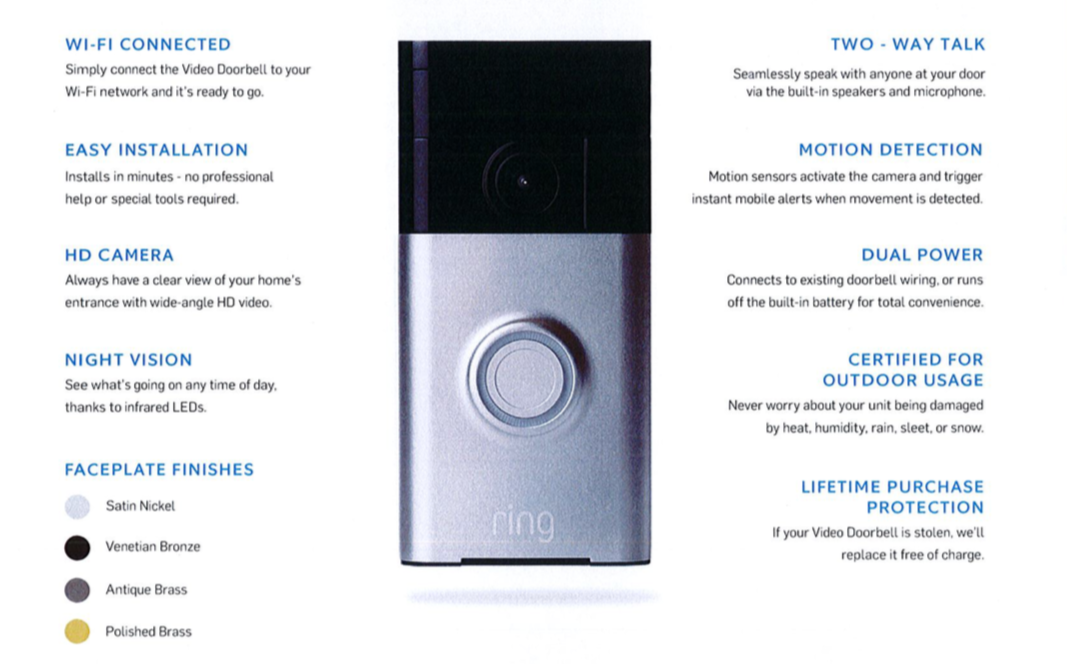

Pastor Terrye Moore, a friend of Randall, first learned about Ring, which is owned by Amazon, through a radio ad. The company sells a variety of home security cameras, which can be placed outside or inside the home. One links to a floodlight. Its best seller allows you to see people who ring the doorbell from your smartphone. Ring also makes Neighbors, an app that allows users to upload footage from Ring devices and other security cameras for anyone to see.

The pastors work together in a church coalition called the Northwest Faith-Based Partnership, so Moore contacted Randall right after she heard the ad. To him, Ring sounded like a godsend. As president of his neighborhood association, he had already asked the city of Baltimore to install street cameras in his neighborhood; the city declined.

Even if Baltimore wouldn’t invest in surveillance, Randall thought, there was no reason why residents couldn’t do it themselves. Moore contacted Ring.

Selling Crime Reduction to the Vulnerable and Scared

Ring, whose stated mission is "to reduce crime in neighborhoods," gives hope to people who feel unsafe, can’t trust the police, or simply want to take surveillance into their own hands and become watchers.

Although there’s no credible evidence that Ring actually deters or reduces crime, claiming that its products achieve these things is essential to its marketing model. These claims have helped Ring cultivate a surveillance network around the country with the help of dozens of taxpayer-funded camera discount programs and more than 600 police partnerships.

When police partner with Ring, they are required to promote its products, and to allow Ring to approve everything they say about the company. In exchange, they get access to Ring’s Law Enforcement Neighborhood Portal, an interactive map that allows police to request camera footage directly from residents without obtaining a warrant.

Ring, has, among other things, helped organize police package theft sting operations, coached police on how to obtain footage without a warrant, and promised people free cameras in exchange for testifying against their neighbors.

In recent months, people have started to mobilize against these partnerships. Fight for the Future, a digital-rights activist group, launched a campaign in August to help people demand that their local governments and police departments stop partnering with Ring. In October, 36 civil rights groups signed an open letter demanding an end to Ring’s partnerships with police, new regulations, and a congressional investigation into the company.

Ring has a host of competitors. Some, like Google’s Nest, Arlo, and Wyze, focus on consumer-grade products, while others, like ADT, offer professional-level services. But a few things set Ring apart. It offers tools for police, like the Law Enforcement Neighborhood Portal, as well as Neighbors, a free, crime-focused social media app available to anyone. It also has a uniquely large scope of partnerships with law enforcement and a history of troubling privacy practices. At least in the past, footage from its cameras was open and accessible to company researchers in Ukraine in order to test developing facial, object, and voice recognition systems. (Ring denies that this is still the case.)

Most crucially, though, Ring is owned by Amazon. This makes Ring not just a camera company, but a node in Amazon’s network of Alexa-enabled smart home devices.

This amounts to a picture of paralyzing scale: Amazon, one of the three largest publicly-traded companies in the world, owns a company that has been quietly building a privatized surveillance network throughout the United States. This network is only possible because consumers choose to buy the cameras themselves. Why do people make this choice? There are as many answers as there are Ring customers, but there is also one answer that explains everything the company has done: At its core, Ring is a marketing company that realized it could make money by selling fear.

As a Ring blog from 2016 says, “Fear sells.”

Ring’s Founder

Jamie Siminoff, the founder of Ring, never set out to create a private surveillance network. He is fundamentally an entrepreneur—a founder, an inventor, a man infatuated with Silicon Valley disruption and start-up culture.

Siminoff has long been enthralled by the idea of the great entrepreneurs. His personal Tumblr, which he used between 2008 and 2013, is filled with inspiring quotes from the likes of Bill Gates, Elon Musk, and Steve Jobs. He frequently referred to WIRED magazine and TechCrunch, journalistic hubs for the tech optimism of the late-aughts and early teens. He posted frequently and anxiously about the recession and the effect that it was having on tech start-ups.

His dream was to become an icon. He wanted to change the world. He was ambitious. He was also afraid of failure.

“I live in fear,” Siminoff wrote in a 2008 post about one of his former businesses. “Maybe it comes from my parents, my father was always planning for ‘what if’ scenarios or maybe I am just scared.”

“There were nights when I woke up at 3 a.m. in tears, bawling,” Siminoff told Inc about his experience with Ring between 2015 and 2017. “How were we going to make it to tomorrow? Luckily, no matter how mentally hard that was, I had one choice, which was, ‘Pick yourself up, Jamie, and get back out there.’ Because stopping would have resulted in the end."

But on a fundamental level, Siminoff also embodies the optimism of the disruptor. Disruptors are optimistic that the machine of modern capitalism will work as designed and either get them rich, make the world better, or maybe both.

Siminoff’s dream of becoming a famous entrepreneur began when he was young. He said in a 2008 interview that in high school, he got a gig as a sales representative for a company selling paramotors, which he described as “these flying machines with a fan in a backpack for an engine and a parachute.” (He claims they cost about $13,000 each, and that he made a $6,000 commission for each one he sold.) At the time, he was attending Morristown Beard, a private, co-ed school in one of New Jersey’s wealthiest counties.

Siminoff got a degree in entrepreneurship from Babson College, a small, business-focused school in suburban Boston. He went on to create four companies in 10 years, two of which he sold.

In 2011, Siminoff founded Edison Jr., a company dedicated to brainstorming constantly and acting on the best ideas, according to his Tumblr. After launching several moderately successful projects, Siminoff’s team came up with something called DoorBot in 2012. It was conceived as a doorbell with a camera that lets people see who’s at the door from their phone—“Caller ID for your door,” according to Siminoff.

DoorBot wasn’t a home security product. It was a little tool selling smart-home convenience.

But Siminoff seemed to know, even in its early days, that DoorBot had more potential than any product he had created before. His second-to-last post on his Tumblr is a picture of him with his young son, picking up the first factory-made models of DoorBot. “It was such a great milestone for us to achieve,” Siminoff wrote in the caption, “and one that I will never forget as I got to share it with my best friend.”

Ring repeatedly declined to make Siminoff available for an interview, and declined to allow us to interview any company representatives. Direct emails to Siminoff were not returned and were forwarded to Ring’s communications team.

Enter DoorBot

Siminoff says that DoorBot was founded in a garage. In 2012, he was leading a team of five at Edison, Jr. People would, he claims, incessantly ring the doorbell, something he found endlessly annoying.

“I was like, how the fuck can there not be a doorbell that goes to your phone?” Siminoff told Digital Trends. DoorBot was thus posed as an answer to a question perhaps only he had ever asked.

Siminoff has repeated this story in company blogs and in advertisements; a life-size replica of the garage was even displayed at the 2019 Consumer Electronics Show. It’s not hard to see why: The “founded in a garage” story is a cliche among tech company origin stories, the crucial accessory in a rags-to-riches narrative where the intelligent, starry-eyed entrepreneur pulls himself up by the bootstraps and eventually upgrades to multi-billion dollar facilities and grandiose mansions.

The main problem with DoorBot was that people thought it was a lousy product. Reviews through August 2014 were not good. MacSource said that although the idea of DoorBot was cool, the video quality was poor, and that the audio cut in and out. CNET gave the product a 5.6/10 grade, echoing reports of bad video quality and a “hold to talk" button that was “inconsistent at best.” 320 Amazon reviews rated the product an average of 2.3 out of 5 stars. One one-star review, titled “Dumber Than My Old Dumb Doorbell,” said "I would give it zero stars if I could. Nothing worked properly."

The reported problems were consistent: bad video, bad audio, bad WiFi connection. Basically, every feature that required the product to work as advertised didn’t function properly.

Edison Jr. was determined to make the DoorBot succeed. By January 2013, the company had raised $173,893 for the idea. It got coverage from a host of tech blogs, including Mashable, New Atlas, and Digital Trends. Soon enough, though, Edison Jr. was “out of money.”

What changed things was Shark Tank.

Shark Tank is a wildly popular TV show where entrepreneurs pitch their businesses to investors called “sharks.” Simonoff landed a spot on it to pitch DoorBot; the episode aired in November 2013, about four and a half years before Ring was acquired by Amazon.

“If it was not for [ Shark Tank] we would not exist as a company,” Siminoff has said. He’s right. DoorBot would not have survived, and it would not have become Ring, if it had not appeared on Shark Tank. Siminoff, a devoted believer in the merits of capitalism, entrepreneurship, and the power of a great idea, could not have been a better fit for the show.

DoorBot, Shark Tank, and Ring’s Early Days

In early marketing materials, DoorBot was awkwardly portrayed as both a disruptive Silicon Valley product and something that could easily be sold in an infomercial.

The two didn’t mix well. When DoorBot was pitched on Shark Tank, the problem was illustrated quite clearly.

“Consumers are currently spending billions of dollars outfitting their homes with products that work with smartphones,” Siminoff said on Shark Tank. “However, one of the most ubiquitous technologies, the doorbell, has not changed since it was invented in 1880. Until now. Introducing the DoorBot, the first ever video doorbell built for the smartphone. With DoorBot, you can see and speak with visitors from anywhere.”

Siminoff showed the sharks how to use DoorBot to see who was at the door, and then tell them to “scram.”

“Now sharks, join me,” Siminoff said.

“And the next time you hear …” he said, as a doo dah doo doorbell noise played from speakers.

“It’ll be …” Siminoff continued, as a cha-ching cash register noise played from speakers.

Siminoff threw paper bills into the air and let them fall like confetti.

“Now, who wants to be first to ring my bell?” Siminoff asked, pointing both thumbs at his chest.

One by one, four of the sharks declined to invest. Finally, Kevin O’Leary made an offer, but Siminoff turned him down, not wanting to offer O’Leary a 10 percent stake in the company.

He walked away empty-handed, but it didn’t matter. Siminoff would later say that going on Shark Tank “was probably worth $10 million of ads.” One month after the episode aired, in December 2013, DoorBot raised $1 million in seed funding from five venture capital firms. In July 2014, it raised another $4.5 million in funding from two firms.

(Although Siminoff was rejected by the Sharks, a Vimeo clip showing his appearance on the show has been linked in the email signatures of several Ring representatives for years, and cumulatively, circulated thousands of times via email.)

In September 2014, DoorBot relaunched as Ring. DoorBot, a product which sold smart-home connectivity and convenience, was dead. In its place was a Ring, a little box to guard the American home—a vulnerable place, perpetually under threat from the outside world.

DoorBot looked like a fish tank filter with a giant, protruding camera. It was clunky. The only thing that distinguished it from a toy robot was a black doorbell button ringed with a glowing halo in iMessage blue.

The Ring doorbell camera, though, was simple and elegant. Its face was flat. It looked a bit like an iPhone. The black camera on the top was reminiscent of a phone screen; the doorbell, its home button. With the help of industrial designer Chris Loew, the dorky DoorBot gadget transformed into Ring, a sleek and almost menacing home-security product that demanded to be taken seriously.

When DoorBot became Ring, the tone of the advertisements shifted dramatically. DoorBot commercials talked about “convenience” and about making our lives “more connected.” DoorBot was, at its core, an extension of the home.

Early Ring advertisements, on the other hand, began with scenes of the home under siege. One commercial shows robbers cascading through windows in the middle of the night. They rummage through an immaculate home with military efficiency.

"They want you to think this is what a home burglary looks like," Simonoff says confidently. “But over 95 percent of break-ins actually occur in broad daylight, which is why I invented the Ring video doorbell."

Ring’s mission changed for one core reason. DoorBot sold “disruption” in the package of a doorbell, but fear is more powerful than the optimism of disruption. And Siminoff is a passionate entrepreneur who was willing to do anything to help his business survive.

The Brave New World of Ring

In 2015, Ring struck a deal with Wilshire Park, a small community in Los Angeles home to about 500 people. The company installed free doorbells on about eight percent of the homes in the neighborhood. According to police, home burglaries dropped astronomically.

The results earned nothing but positive media coverage. And, most importantly, it’s been at the core of Ring marketing efforts for the past several years. Representatives in charge of organizing partnerships and discount agreements with police often include a link to Wilshire Park media coverage in their email signatures, according to thousands of emails from between 2017 and 2019 reviewed by Motherboard.

Information about Wilshire Park is also included in official Ring promotional materials. "After installing Ring Video Doorbells on 41 homes in the L.A. neighborhood of Wilshire Park, there was a 55% reduction in home burglaries from June to December 2015 compared to the same seven-month period in 2014," one Ring flyer reads.

It’s unclear if this is actually true: We don’t have any of the data or methodology that lead to the figure of a 55 percent reduction in crime, so it’s impossible to verify the claims of Ring and the LAPD. As Mark Harris reported for MIT Technology Review, though, the neighborhood districts that make up Wilshire Park in fact had year-on-year increases in burglaries during the June-to-December period.

This of course doesn’t mean that Ring causes crime, or even that its claims are inaccurate; the point is that there’s simply no way to evaluate them. “Without knowing the exact location of the test and which surrounding areas Ring used for comparison,” as Harris wrote, “it is impossible to check the company’s claims against the public data.” As he also notes, a scientifically rigorous study would involve studying the effects of many more doorbells across dozens of districts over a longer period of time.

But Ring’s venture in Wilshire Park has since been offered as powerful evidence of the efficacy of their devices. It also came at a time when Ring was entering into new relationships with law enforcement. In August 2016, for example, Ring tapped into Washington, DC’s "Private Security Camera Incentive Program,” which allowed residents to get $200 to $500 rebates on security cameras purchased after a particular date.

The Wilshire Park “case study” and the Private Security Camera Incentive Program collectively launched a new era in Ring’s history. The company realized that by reaching out to city governments and law enforcement, it had the ability to tap into a growing market of tech services aimed at law enforcement.

Why Did Amazon Buy Ring?

It wasn’t a complete surprise when Amazon bought Ring in 2018 for about $839 million. Amazon had already been heavily investing Ring for about two years.

Using the Alexa Fund, its venture capital fund, Amazon funneled millions of dollars to Ring in both 2016 and 2017. (Amazon has acquired at least six start-ups that it once financed through the Alexa Fund, according to its website.)

We don’t know exactly how much money Amazon gave Ring in those two years. But we do know that Ring raised a total of $61.2 million in venture funding in 2016, and $109 million in 2017. Amazon was a top investor for Ring in both of those years, according to business database CrunchBase.

Official press statements from Amazon and Ring say that the goal of the acquisition is to “accelerate” Ring’s mission of reducing crime. Amazon’s press release from 2018 uses this language, and so does Siminoff in his quoted statements.

“Together with Amazon, we will accelerate our mission dramatically by connecting more Neighbors globally and making our security devices and systems more affordable and accessible,” Siminoff said in both a Ring press release and an Amazon press release.

(The price on Ring products has not gone down since the company was acquired by Amazon. The Ring Doorbell 2, for instance, cost $194 in 2017. It costs $199 on Amazon now.)

However, there’s evidence that Amazon acquired Ring for two main reasons. One is that Amazon wanted to expand its line of smart-home products, which includes the Echo Dot, smart plugs, smart lights, and the Alexa-compatible Fire TV. The other is that Amazon wanted a way to deter or go after package thieves, since the company loses money whenever packages are delivered but stolen.

Amazon does not publicly say that Ring is meant to help secure packages. However, we do know that Amazon has a vested interest in making sure customers get what that were shipped, and that it protects that interest. Amazon Fulfillment, the part of the company that deals with package delivery, has a loss-prevention unit in charge of protecting products in the supply chain. This part of the company has worked directly with Ring, and with police, to combat package theft through sting operations.

These package-theft sting operations involve creating bait Amazon packages, using tape and boxes provided by Amazon, and putting the packages on doorsteps equipped with Ring doorbell cameras. They have occurred in Hayward, CA; Aurora, CO; Albuquerque, NM; and Jersey City, NJ, and Motherboard has obtained documents regarding these operations from Hayward, Aurora, and Albuquerque.

The documents reveal that an explicit goal of these operations was to catch someone stealing a package on a Ring doorbell camera and arrest them. Another goal was to get as much media coverage as possible. Amazon, Ring, and the police spent days discussing local news coverage and meticulously rewrote press releases. Even though none of the operations resulted in any known arrests, there was a strong incentive for all the parties involve to appear as if they are tough on crime.

Documents that Motherboard obtained from Albuquerque reveal that Amazon keeps precise data about package loss. The company shared “heat maps” showing the prevalence of package loss in Albuquerque zip codes on 60-day and 12-month scales. The fact that Amazon keeps this data shows that the company takes package loss seriously. Likewise, the fact that it shared this data with police shows that Amazon wants package loss to end.

Andrew Ferguson, a professor at the University of the District of Columbia's law school, said that Amazon may have also been motivated to purchase Ring because of its existing relationships with law enforcement. As noted by Ferguson, Amazon is constantly looking for new markets for Amazon Web Services, Amazon’s profitable cloud computing business.

“Amazon sees local government as a big purchaser of those [cloud] services, and sees law enforcement as an easy way in to gain those bigger contracts from local government. And that the services they are offering—the recognition facial recognition software, the Ring cameras, and Neighbors—are all just bells and whistles to a much more profitable business, which is cloud storage.”

In an email statement to Motherboard, a Ring spokesperson said that the company’s “mission is to help make neighborhoods safer, and with that mission in mind, we’ve designed products and tools that connect communities while protecting user privacy.”

“We believe that when communities work together, safer neighborhoods become a reality,” the spokesperson said. “Ultimately, Neighbors app users can choose how they want to interact with their community.”

When Ring Comes to Town

Ring was a product of Siminoff’s love of disruption, the idea that a tech-savvy dreamer who doesn’t take no for an answer can change the world. Ring has changed the world, but almost certainly not in the way that Siminoff originally imagined.

Siminoff’s invention didn’t just apply a “smart home” sheen to the doorbell. It became a part of Amazon’s configuration to solve package theft. It infiltrated the day-to-day operations of hundreds of police departments. It created a culture where it’s OK for millions of people to watch not only each other, but themselves. And crucially, it became a last-resort for people are rightly afraid of the police, and rightly fear for their safety.

In Baltimore, Randall said that when they got in touch with Ring, the company immediately wanted to help.

“I’m telling you, the turnaround was absolutely crazy,” Randall said. “They got on the plane and came to meet with us maybe a week or two later.”

Randall explained what his neighborhood was going through, and Ring said it could fix it. The company’s representatives claimed that installing cameras throughout a community can deter drug activity and lower crime. Ring told them it had “done it in other cities,” he said, and it could do it in Baltimore as well. They offered to provide 150 doorbell cameras, which normally cost about $100 each, for free. All the neighborhood would have to do is pay $3 per month for the cloud-storage fees associated with saving footage from each camera—$5400 a year, in all.

Randall and Moore applied for a city grant on behalf of the Northwest Faith-Based Partnership, and in October 2018, they won $15,000 to pay for cloud storage and camera installation. There was one catch: The Baltimore Police Department would have to sign a contract with Ring and the Northwest Faith-Based Partnership before Ring would hand over the cameras.

At the time of writing, the Baltimore Police has not signed a partnership contract with Ring. But over 600 other law enforcement agencies have, and this number grows almost daily.

In addition to conducting outreach to associations like the Northwest Faith-Based Partnership, Ring also conducts intense outreach to law enforcement. This outreach has become central to Ring’s marketing strategy.

Since its stint on Shark Tank, Ring has continued to invest heavily in television advertisements. But the company also realized that in order to continue to grow as a home security company, it would need to be promoted by the population that people most closely associate with addressing crime: the police.

In part two, we’ll explore Ring’s intensive outreach efforts to law enforcement, and its efforts to get police on its side.

But for ordinary people, like those in Northwest Baltimore, the reason for trusting Ring is simple: they are scared. Pastor Moore said that he understands concerns that people have about Ring’s use of data. However, he said his community didn’t share these concerns.

“When I presented it to the community, we didn't have any problems, we didn’t have any kickback,” Pastor Moore said. “People welcomed it because they’d been so downtrodden and so held captive that they would take anything at this point.”

This article originally appeared on VICE US.