Mira T. Sundara Rajan: Don Cherry rant showed disregard for true story of First World War veterans

Credit to Author: Hardip Johal| Date: Fri, 22 Nov 2019 18:00:33 +0000

The poppy is a simple yet potent symbol of the sacrifices made by the young men of a century ago, and by all who loved them. Young people who gave up hope, love, family and life itself to fight for peace and freedom.

It is movingly invoked in an immortal poem by Canadian soldier John McCrae, which, as a young child in Saskatoon, I listened to every year as it was read in our school Remembrance Day services.

“In Flanders fields the poppies blow/Between the crosses, row on row,/That mark our place…”

What a curious symbol to become the focus of an anti-immigrant outburst, like the one that Don Cherry made earlier this month. What upset me most about it was not only the routine denigration of immigrants who came to Canada to enjoy this country’s “milk and honey” — originally inhabited anyway, lest we forget, by Canada’s Indigenous peoples who met with cruelty and brutality at the hands of the European “immigrants” — that is to say, colonists — of the day.

What was equally bothersome about it was its disregard for the true story of the veterans of the First World War. Yet these are the very people that the poppy is meant to remember and honour on this extraordinary day.

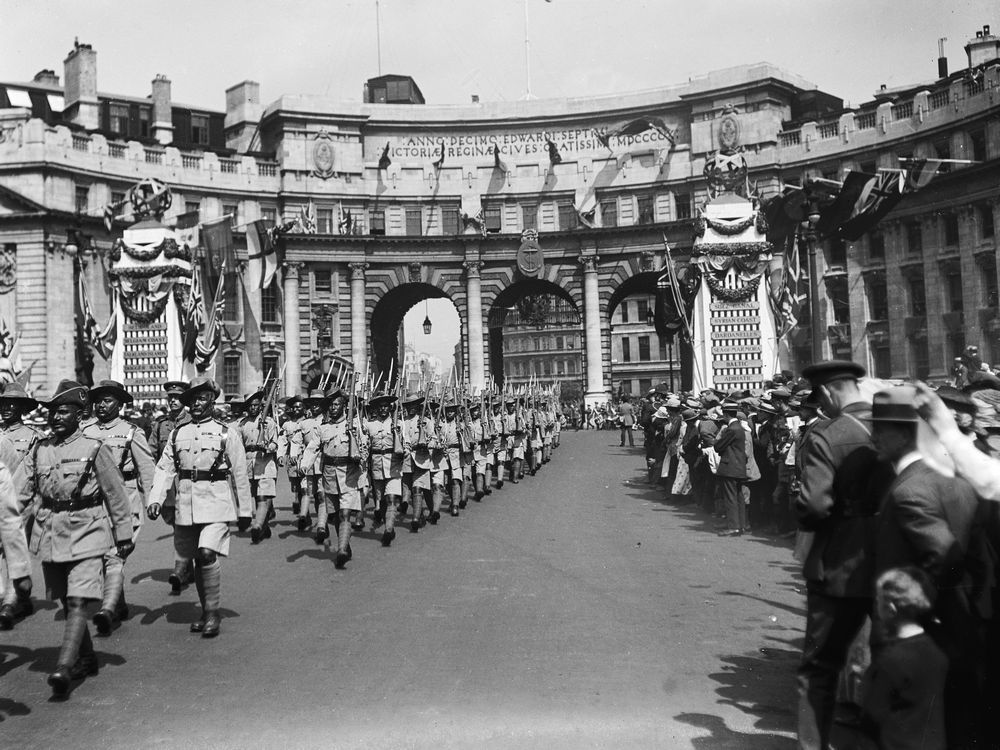

The Allied soldiers of the First World War were drawn from every part of what was then a vast and diverse British Commonwealth — the largest political entity, the most universal empire, ever known to humanity. They came not only from Canada, but also from countless other countries and regions. Numbering around three million, this army included soldiers of various nationalities, religions and ethnicities. From India alone, as the British National Army Museum notes, some 1.27 million men “voluntarily served as combatants and laborers.”

The reasons behind their participation were complex. In India, British rule was maintained into the 20th century, against the will of both the Indian people and many British social reformers. The mercantilist trade system saw the systematic export of Indian wealth from India to Britain over a period of close to two centuries, leaving the country impoverished. On this point, Cherry is quite right: By the time the British were through with India, there was little “milk and honey” left behind for the Indians.

Hockey commentator Don Cherry.

And yet, many Indians believed in the British war effort and felt that India should support it. This included Indian nationalists who passionately fought against British rule. My great-grandfather, Indian national poet C. Subramania Bharati who lived from 1882 until 1921, was one of them.

Why would Bharati and others like him support the British at such a time? The reasons can be found in a moving essay written by Bharati on this very subject, in the English language, entitled, “India and the War.” Writing in 1915, he said, “from whatever philosophical height one may choose to survey the momentous struggle now going on in Europe, one cannot help taking sides unless one ceases to be human. The thing is so grand, so terrible, so tragic, so human. It is a pity that men should have to die like this.”

There can be no doubt about why Bharati thinks these sacrifices are worthwhile: They are the price that must be paid for freedom. He says so in the clearest possible terms:

Digital artist Mark Truelove’s colourized image of Canadian Pioneers carrying trench mats with the wounded and prisoners in background during the Battle of Passchendaele in November 1917, one of the fiercest battles for Canadian in the First World War.

“Man generally learns new lessons at a frightful cost. In Europe, today, the Allies maintain that they fight for international equity, for the rights of nations and individuals …

“We must forgive the past. There remains no doubt … that in the present war, the right is with the Allies. And we in India — all of us who count for anything — being passionate lovers of the cause of freedom, we pray that the side which will guarantee the freedom of nations, which will demolish once and for all the stupid doctrine that “Might is Right,” which will establish a permanent and universal system of international equity and mutual respect — that side should win. This is the reason why India is so willing to sacrifice her men and resources towards aiding England and her allies.”

For Bharati, such statements represented deep personal renunciation. Supporting the war meant putting aside the blazingly urgent cause of Indian freedom from British rule — a cause to which Bharati had dedicated his life, which led to the proscription of his writings in British India and forced him to flee to Pondicherry, a territory administered by the French on Indian soil, to live in exile among the larger community of nationalist fugitives as they continued to fight for Indian independence from their French base. Bharati’s impetuous, poetic temperament demanded the immediate, instantaneous resolution of injustice. For him, Indian independence could not wait one day, one hour, longer. Yet, wait it must.

Commentator Mira T. Sundara Rajan, pictured in 2009.

He comforted himself: “England will never forget India’s generosity and magnanimity. She will not disappoint the civilized world by denying her present ideals when the war is over.”

He was right, though the results were not to be seen until another World War and the catastrophic consequences thereof had run their course.

All of these men died in the cause of freedom — Indians like Canadians, like New Zealanders and Australians, like West Indians, like so many others. There are more than can be remembered in a few lines of prose, or poetry. But we can find symbols to help us remember, to reflect the unimaginable splendour of their sacrifice, to convey its meaning directly into our minds and hearts. A symbol can speak across the generations.

The poppy, bright and frail, is one of these, most precious symbols. It reminds us of the universality of human experience — something that we need to recognize in today’s world with an urgency that even Bharati and his contemporaries could hardly have dreamt of. Let us see the poppy as it was meant to be seen — as a reminder of basic human values and of those who have sacrificed to uphold those values around the world — not as one more means of excluding “immigrants” from some exclusive Canadian club. It represents all lovers of human freedom and dignity, everywhere.

Mira T. Sundara Rajan is a Canadian law professor and currently a visiting scholar at UC Hastings in San Francisco. She is a great-granddaughter of C. Subramania Bharati.

CLICK HERE to report a typo.

Is there more to this story? We’d like to hear from you about this or any other stories you think we should know about. Email vantips@postmedia.com.