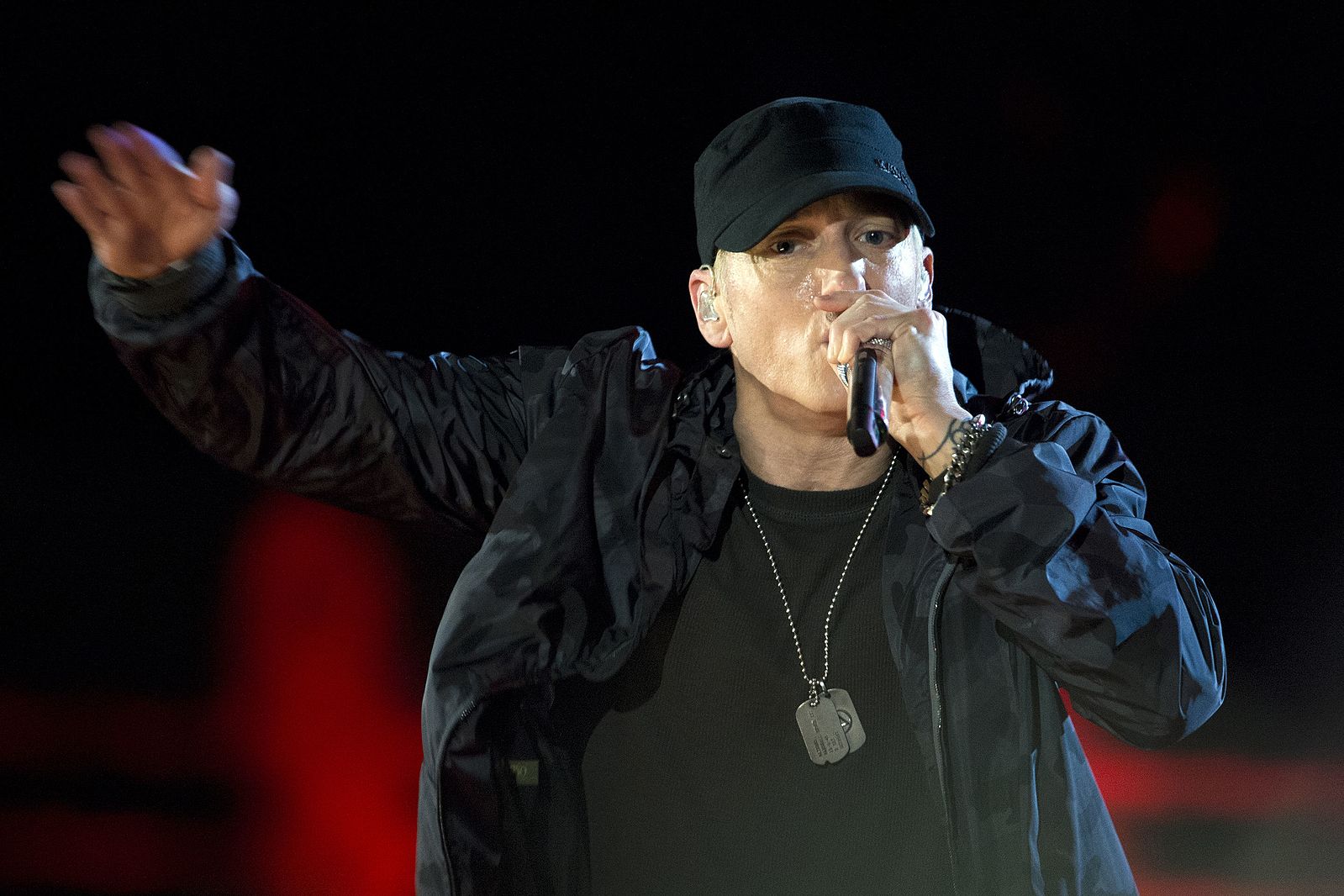

Ask A Lawyer: What’s Going on With Eminem’s Spotify Lawsuit?

Credit to Author: Jessica Meiselman| Date: Thu, 29 Aug 2019 12:03:46 +0000

Last week, Eminem’s publishing company filed a lawsuit against Spotify alleging that the streaming giant has been generating revenue from some of the Detroit rapper’s biggest hits without properly licensing them. The company, Eight Mile Style, is seeking millions in unpaid royalty payments as well as hefty statutory damages, or fines. Moreover, Eight Mile is alleging that Spotify is taking advantage of a loophole in the law—specifically, the recently passed Music Modernization Act—to deliberately mislead rights holders and pay them less money than they’re owed.

While this isn’t the first time a publishing company has sued Spotify for unpaid royalties, the implications are significant. Citing a communication from the National Music Publishers Association, the complaint estimates that since 2011, Spotify has racked up between $60-120 million dollars in unpaid songwriter royalties due to artists from all across the music spectrum. Likening Spotify’s business practices to those of the “primitive illegal filesharing companies” of yore (read: Napster, Limewire, et al), the suit posits that if the company failed to pay royalties for a song like “Lose Yourself,” the Detroit rapper’s chart-topping contribution to the 8 Mile soundtrack, “smaller publishers never had a chance to be paid or paid properly.”

This is all quite technical, so let’s break it down a little: a streaming service like Spotify needs to obtain two sets of clearances to distribute a song: the rights to the master recording (usually owned by a record label) and the right to the underlying composition, or “mechanical right” (typically owned by a writer). Record labels bring recordings to the service, but it’s up to Spotify to obtain permission to reproduce the underlying composition, via a process known as “matching.” Spotify employs a rights management provider, the Harry Fox Agency, to handle this part of the process—”matching” recordings to compositions and paying out mechanical royalties on behalf of Spotify for the use of those compositions.

Spotify has faced blowback over the mechanical rights issue before. Wixen Music Publishing—a publisher that services thousands of artists, including Tom Petty and Missy Elliott—sued Spotify for $1.6 billion in late 2017, claiming that the company had failed to properly license the underlying compositions for a number of recordings. In May 2017, Spotify settled a class action lawsuit with a group of publishers for $112.55 million on similar grounds.

The passage of the Music Modernization Act in 2018, which requires Spotify to take certain actions if it cannot “match” recordings with compositions, was supposed to clarify some of the ambiguities around mechanical licensing that gave rise to these claims. Still, it’s unclear to what extent the MMA is actually helping artists. And if an artist like Eminem is alleging underpayment, it’s reasonable to think that less prominent artists have been affected too.

The MMA, which was signed into law in October of last year, included provisions that addressed this “matching” problem, including a plan to create a centralized database of rightsholders. Notably, the act allows digital service providers like Spotify to avoid some liability for unpaid songwriting loyalties, provided they follow certain procedures. Streaming platforms are obligated to undertake “commercially reasonable efforts” (a legal standard that sets a low-ish bar in terms of effort) to locate the owner of the composition. If they fail, they must send a “Notice of Intent” to parties they believe to own some or all of the composition—and if they cannot find anyone, to the US Copyright office. The streaming platform is then required to set aside royalties at a rate set by law. After completing this protocol, the company obtains a “compulsory license” which enables it to continue distributing the composition without having to negotiate with the publisher.

Unfortunately for artists and publishers, the MMA eliminated the ability for rightsholders to claim statutory damages and reimbursement for attorney fees for claims filed after December 31, 2017, rendering legal action against streaming companies like Spotify prohibitively expensive for most artists—and much less potentially lucrative. Of course, it was a pretty good deal for Spotify: Because the MMA eliminated statutory damages (which, at $150,000 per infringement, can quickly add up) and other significant legal remedies, the company could mostly rest assured that if it held up its end of the deal, it wouldn’t be facing any more billion-dollar lawsuits.

But Eight Mile is arguing that Spotify failed to follow the protocol. Specifically, the suit alleges that the company intentionally misused a “safe harbor” (or loophole) in the MMA to claim they had a license without actually obtaining one, thereby robbing Eight Mile of its rightful royalties and other legal remedies. Instead of taking steps to notify Eminem of the unmatched compositions, the suit argues, Spotify claimed in bad faith that it was unable to locate the rightsholder—thus depriving Eight Mile of a chance to negotiate a higher payment rate and potential equity in Spotify itself. The publisher is also going one step further and alleging that Spotify made intentional efforts to withhold payment, claiming that the company simply ignored the knowledge it had about ownership of the compositions. After all, Spotify had to know that Eight Mile was the owner of the disputed compositions, Eight Mile says, because it paid some royalties to Eight Mile before the MMA was enacted.

Spotify’s agent, Harry Fox, has escaped some scrutiny here, though the Wixen and Eight Mile lawsuits certainly cast doubt on how successful the company has been in matching compositions with rightsholders. Where the Wixen complaint posited that HFA was “ill-equipped to obtain all the necessary mechanical licenses,” the Eminem suit gets a little bit more granular,

criticizing HFA for failing to use commercially available matching technology—which certainly rings true, seeing anyone can go on BMI.com, search an artist’s repertoire, and identify that Eight Mile Style owns 90 percent of the publishing rights to the song “Lose Yourself.”

Highlighting the HFA’s alleged inefficiencies, the suit points to a 2016 settlement between Spotify and the NMPA after which the HFA succeeded in matching only 15 percent of all previously unmatched compositions. Eight Mile alleges that the remaining 85 percent was “paid out by market share with the bulk of the revenue going to Spotify equity owners Universal, Sony, and Warner,” although VICE has not independently verified these claims from the complaint. In any case, what Eight Mile is arguing is that failing to match recordings actually further enriches Spotify and its owners, including the major labels that own 16% of the company.

In late 2018, Wixen and Spotify reached a settlement and announced that they would be entering into a partnership that “establishes a mutually-advantageous relationship for the future.” According to Eight Mile’s complaint, this relationship probably includes equity in Spotify, and that is likely what Eminem’s publishing company is seeking here. As Spotify’s market cap continues to increase, the Eight Mile complaint observes, Spotify is “[n]otably not sharing in these billions of dollars [with] music publishers like Eight Mile, or songwriters like Eminem, whose songs are the only assets Spotify has to attract the users that increased Spotify’s value.” Seeing as the Spotify has already ceded some ownership to record labels, Eight Mile seems to be making the case that composition owners should be able to share in the company’s profitability as well.

If Eight Mile succeeds in entering into a “mutually advantageous relationship” with Spotify in the context of a settlement, you can expect more publishers to attempt to follow suit. And yet, though Eight Mile’s insists that it is standing up for smaller artists, it remains to be seen whether such an outcome will open any doors for artists who don’t have hit singles or powerful legal teams.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.