From ‘The Alcatraz of the Rockies’ to the Streets

Credit to Author: Keegan Hamilton| Date: Wed, 28 Aug 2019 12:21:14 +0000

She had just stepped out for a cigarette break when he walked up and asked to borrow her lighter. Smokers often congregate in the small park across from the hospital where she worked as a lab manager, but something about him gave her the creeps. He was jittery and standing just a little too close. She handed over her lighter and noticed his plastic wristband, which showed he’d been a patient in the ER that day.

She pocketed her phone and checked her surroundings. It was around 3 o’clock on a clear, windy February afternoon in Newport News, on the southeast Virginia coast. He struggled with the lighter in the breeze, so she offered up her lit L&M Red for him to use instead. He glanced at the nametag on her scrubs, then asked: Don’t we know each other from high school?

“No,” she replied. “We don’t.”

“I am pretty sure your sister ran track,” he said. “We used to go to parties together.”

He had an athlete’s chiseled build, but she was sure there was no connection from the track team. She was 28. He looked a decade older. She brushed him off, but he wouldn’t let it go.

“You have a tattoo on your ankle and a mole on your stomach,” he said. “I will give you a thousand dollars to prove it.”

“No.”

He took another step closer, and she took several back. She could see another woman nearby walking toward the hospital. He pivoted as if to leave, then turned back around. She shouted for the other woman to call security, then heard him say: “Bitch, I’m going to kill you!”

He punched her in the face and grabbed her by the throat as she yelled for help. She hit the ground and took another punch to the face. His hands closed around her neck.

“I’m going to kill you, I’m going to kill you, I’m going to kill you,” she heard him say. Her vision started to blur. He tore open the front of her shirt and her bra and pulled her pants and underwear down to her knees.

“I thought, ‘I’m going to die in this field today,’” she testified. “And that ticked me off, so I kind of grabbed onto his arms and flipped over.”

He stood up and walked toward a bus stop about 50 yards away, where two men had stood and watched the incident unfold. She fumbled to find her glasses on the ground and called 911. The police arrived minutes later to make the arrest.

Three days earlier he’d been released from prison, the cops said.

He’d spent the past 11 years in solitary confinement alongside some of the world’s most notorious terrorists, spies, kingpins, and murderers.

When Mary — who asked that her last name be withheld — read the local news, she learned her attacker’s name: Jabbar Currence. When she googled it, she got thousands of hits. He’d been involved in a lawsuit against the Bureau of Prisons over conditions at the United States Penitentiary, Administrative Maximum Facility in Florence, Colorado.

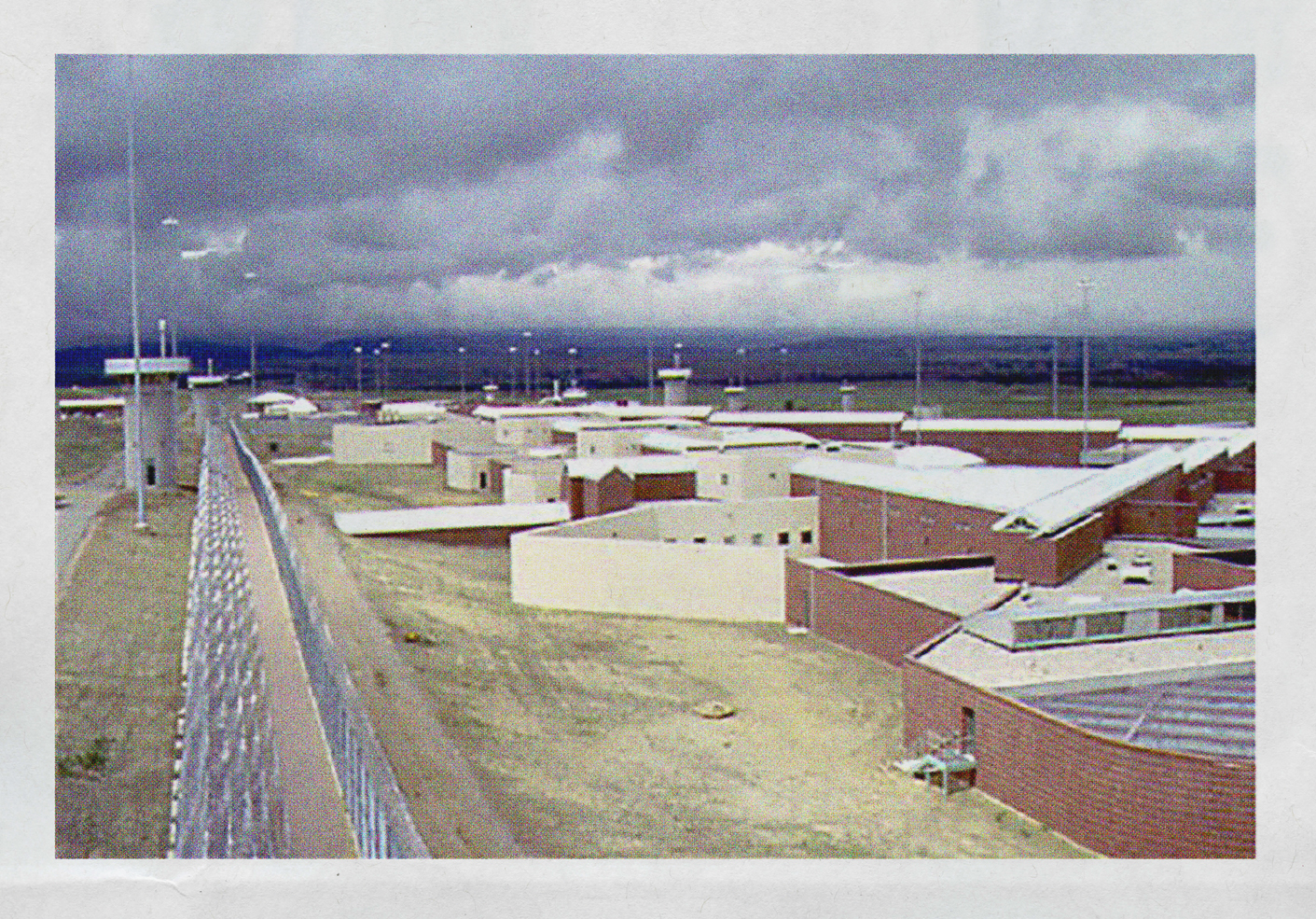

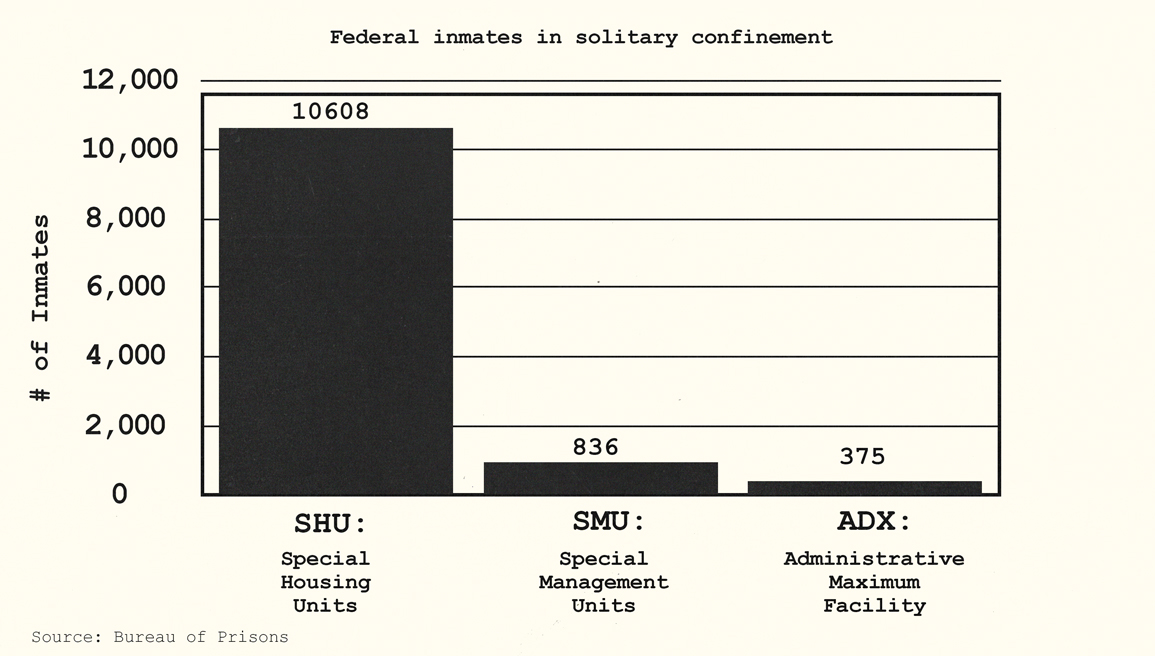

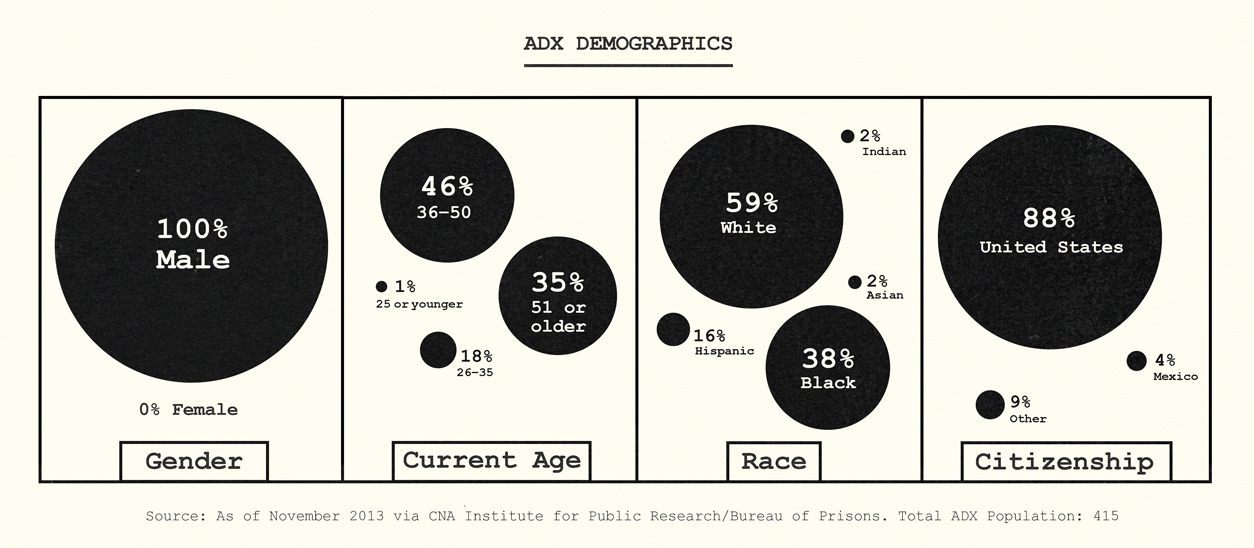

Also known as The Alcatraz of the Rockies or simply ADX, it is the most secure prison in the United States. Of the federal prison system’s approximately 150,000 inmates, the 375 or so at ADX are often described as “the worst of the worst.” Every prisoner is housed in solitary confinement, most for 22 or 23 hours a day.

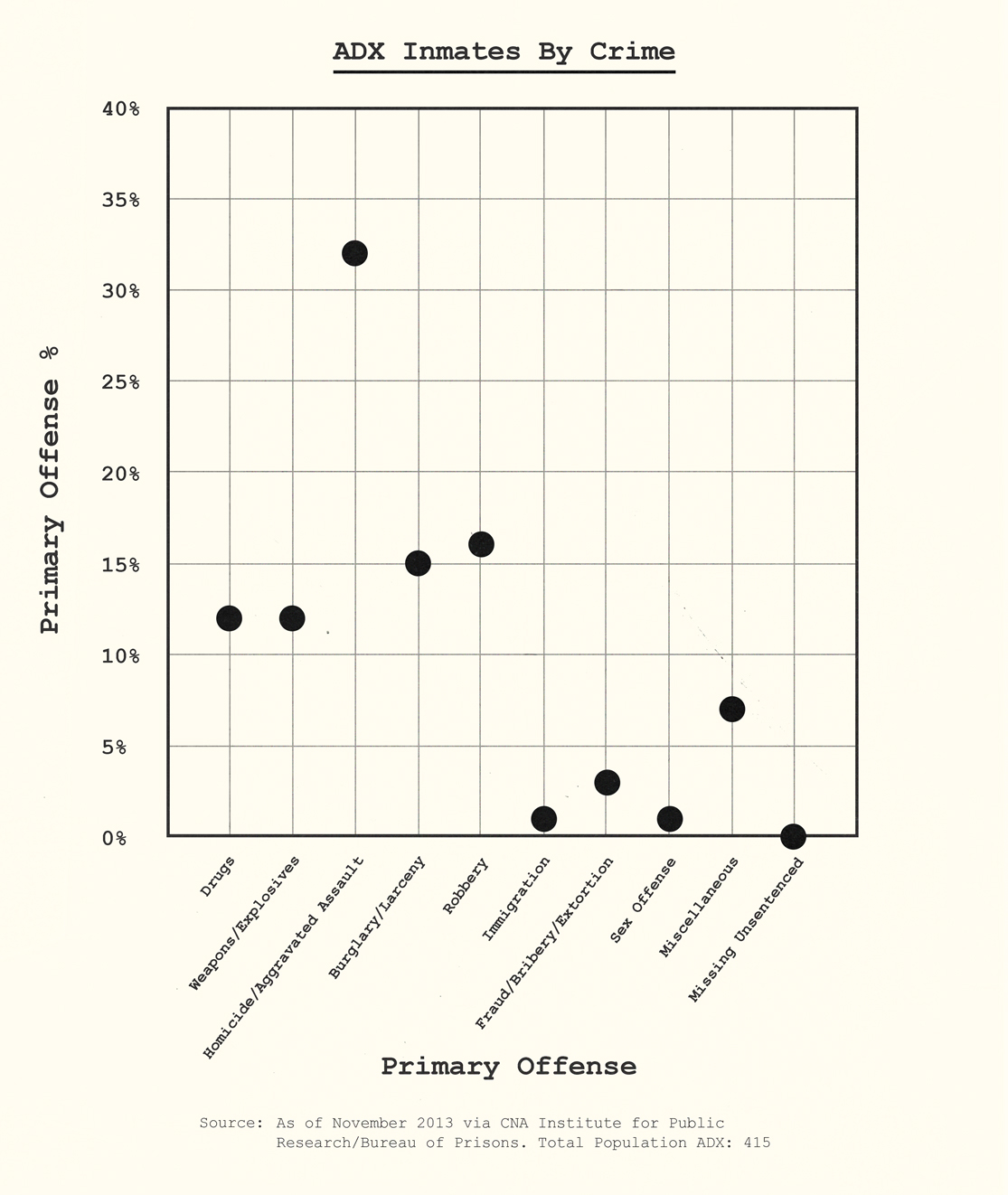

The full ADX guest list is kept secret for security reasons, but the known occupants include World Trade Center bomber Ramzi Yousef, Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, 9/11 plotter Zacarias Moussaoui, Unabomber Ted Kaczynski, and leaders of the Aryan Brotherhood, the Mexican Mafia, the Gangster Disciples, and other powerful prison gangs. Sinaloa cartel leader Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán checked in last month.

But while some ADX prisoners are high-profile criminals serving life sentences, others are relative unknowns who are eventually released after serving their time.

Despite multiple warnings and violent incidents, the Bureau of Prisons has sent severely mentally ill prisoners — including Currence — home from ADX with virtually no preparation or safety net.

At least three others have been either been accused or convicted of serious felonies after being released from ADX:

- Ernest Shaifer: A mentally ill man who spent 10 years in ADX, Shaifer had been out for less than a year when he nearly beat two women to death with a shovel handle in 2015. He’s now serving a 30-year sentence in Florida’s state prison system.

- Antoine Bruce: After approximately seven years in ADX, Bruce was released to his hometown of Washington, D.C., last October. He was free for less than six months before being arrested for allegedly attacking a man with a knife outside a homeless shelter. He claims self-defense and has pleaded not guilty to a felony charge.

- Mario Holmes: A 40-year-old Kansas City man with schizophrenia, Holmes did approximately eight years in ADX after going to prison for bank robbery. He was arrested for another bank robbery in 2014, found incompetant to stand trial, and committed to a mental hospital. In July 2018, after his release from the hospital, he robbed the same bank again. His mother says the robberies were prompted by paranoid delusions exacerbated by her son’s time in solitary. Holmes was again deemed unfit to stand trial and now resides in a high-security federal mental institution.

- Dale Mitchell Lemoine: A convicted bank robber and former ADX prisoner, Lemoine was shot by an off-duty Dallas police officer in 2008 when confronted for stealing from a Walmart. Lemoine, who had a history of mental illness, was wielding a boxcutter when the cop opened fire. Lemoine’s ex-wife said he was placed on a bus from ADX with orders to take his meds and check in with a probation officer in Texas. She heard from his brother that he was killed before the first meeting.

I spoke with 11 former ADX inmates and located seven others through family members, attorneys, and public records. Each story was different, but virtually all the men described receiving little or no preparation for returning to society after years of brutal isolation. Some engaged in self-harm at ADX just to be hospitalized so they could have contact with doctors, nurses, and non-prison staff.

“The way I look at it, after the ADX, what’s left? It’s death row. Next is death row or the graveyard.”

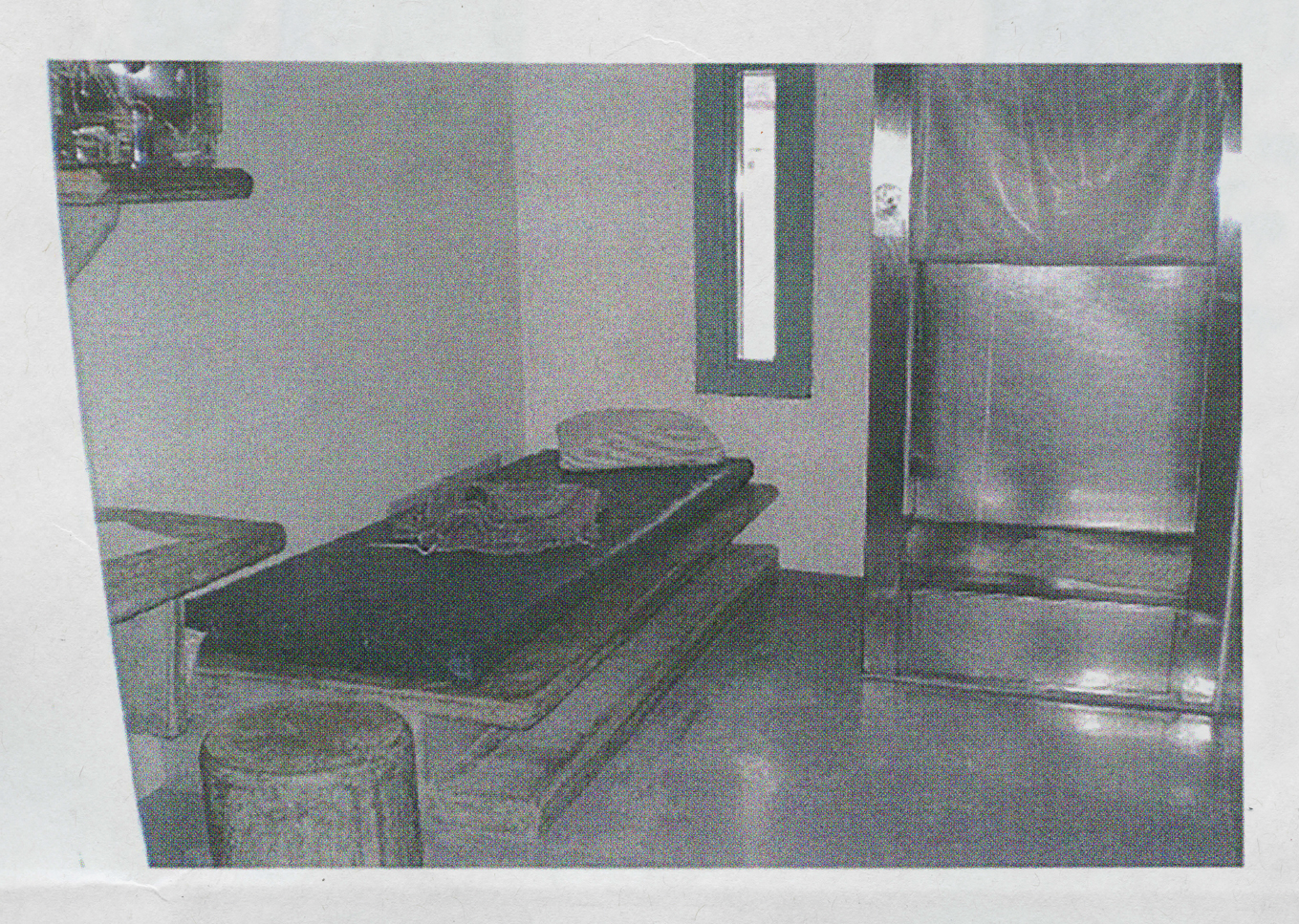

The Bureau of Prisons doesn’t use the term solitary confinement, but everyone at ADX is housed alone, typically in a 7-by-12 concrete cell. Bureau policy officially prohibits mentally ill prisoners from being housed at ADX — except those considered to be an “extraordinary security risk.”

ADX inmates are offered classes and therapy, but those who refuse can end up spending little or no time outside of solitary before hitting the streets. Despite being considered too dangerous for even a high-security penitentiary, and then further damaged by years of isolation, Currence was allegedly unshackled by armed guards in a public parking lot.

“They put him a van, chained him up, and drove him to the halfway house and turned him loose,” said Currence’s attorney while he was at ADX, Ed Aro. “That day he was walking the streets of Norfolk, Virginia. He’d been in a cell by himself for 16 years, then all of a sudden he’s in a dorm-style halfway house.”

ADX Warden Andre Matevousian, who has overseen the prison since early 2018, declined an interview request. In a statement to VICE News, a Bureau of Prisons spokesperson said the agency “seeks to avoid releasing inmates directly from restrictive housing back to the community if this can be done without endangering the safety of the inmate, staff, other inmates, or the public.”

The spokesperson added, “If remaining in restrictive housing becomes necessary prior to release, the Bureau provides targeted re-entry programming to prepare the inmate for his return to the community.”

A request for detailed records about inmate releases from ADX is pending with the BOP.

Federal authorities can seek “involuntary hospitalization” of certain mentally ill prisoners to delay their release. It’s unclear how often, if ever, that tactic has been used, but laws that allow people to be held beyond their sentence are intended only for rare and extreme circumstances. As long as ADX exists, those not serving life need a pathway out.

On a national level, the question of how to humanely treat and rehabilitate violent and mentally ill inmates remains vexing, even as criminal justice reform becomes a bipartisan cause. President Trump recently signed “The First Step Act,” a bill intended to “help reduce the rate of recidivism and offer prisoners the support they need for life after incarceration.” But it’s aimed at people who have committed nonviolent crimes, so it does nothing for the types of offenders that end up at ADX.

The inmates at ADX spend prolonged periods in solitary, even though research suggests long-term isolation can make them more aggressive, more unstable, and more likely to re-offend. Solitary is often justified as the only way to contain the most dangerous prisoners, but less than 3% of federal inmates are lifers. Some of those considered too volatile to be around other inmates will eventually be set free.

“Let’s be honest, it has nothing to do with rehabilitation.”

The ADX cases represent a dangerous paradox in the American justice system’s reliance on solitary. As Mary put it after she learned more about Currence: “If this individual is unsafe in the prison system, where there are safeguards and there are people right there all the time to be able to bring the situation back under control, how is that somebody who should be released back into society?”

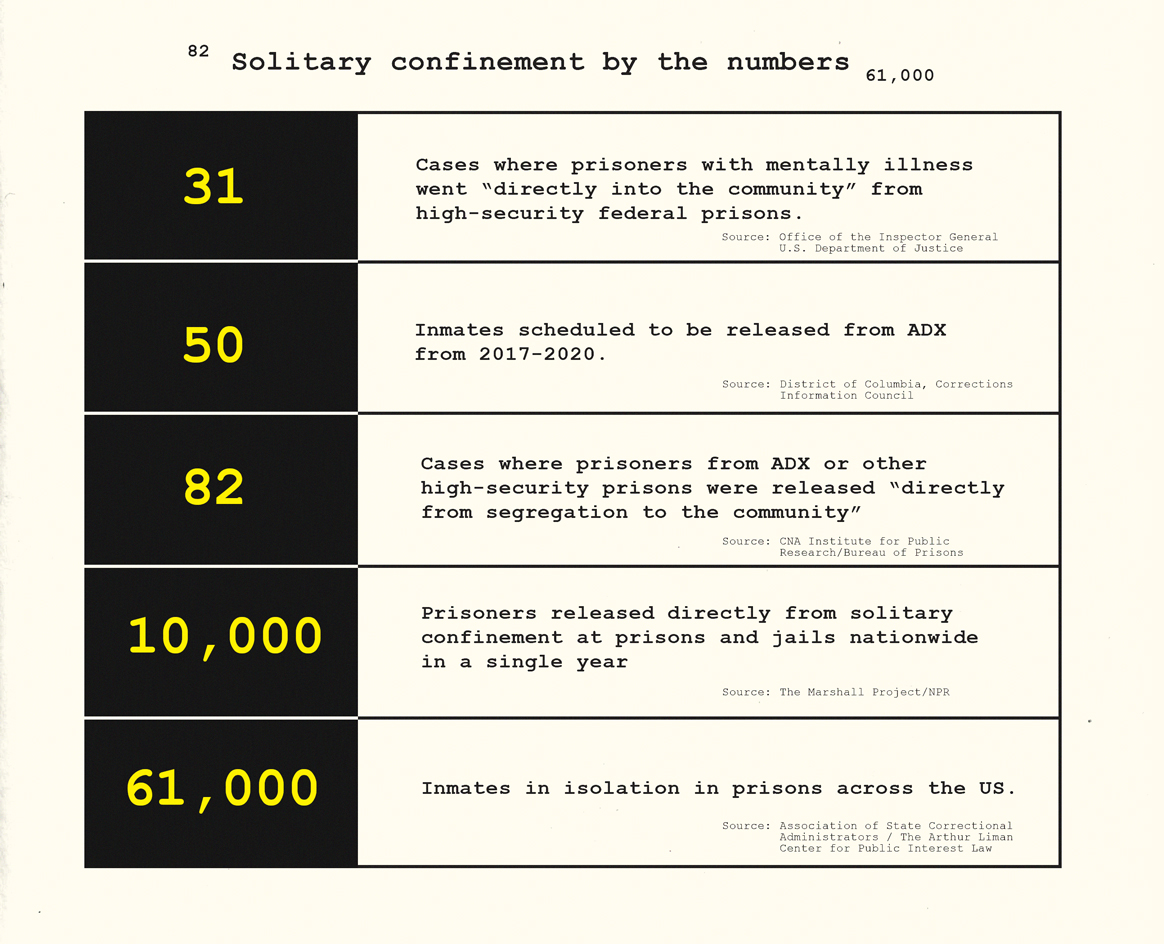

Without detailed records or clarification from prison officials, it’s unclear exactly how many prisoners have been let out of ADX over the years and how many of those have gone on to commit more crimes. A 2014 “review and assessment,” which used data provided by the BOP, found that roughly 60% of ADX inmates — about 250 total — were scheduled to go home eventually. Independent inspectors found last year that around 50 inmates at ADX were scheduled to be released from 2017 to 2020.

And it’s not just ADX. Public data is limited, but there is evidence that federal, state, and local authorities release prisoners directly to the streets after long-term stays in isolation.

- The 2014 report identified at least 82 cases where prisoners from ADX or solitary units at other high-security prisons had been discharged “directly from segregation to the community.”

- Over 2,000 federal inmates were due to be released in 2014 from “Restrictive Housing Units,” the federal government’s preferred euphemism for solitary confinement, according to BOP data.

- As of 2017, there were roughly 10,000 federal inmates in “Restricted Housing Units,” according to the Justice Department’s Office of the Inspector General. The office found at least 31 cases where mentally ill prisoners went “directly into the community” after an average of over two years in high-security units where solitary is the norm.

- A 2018 report from The Vera Institute of Justice found that North Carolina alone had released nearly 1,900 prisoners “directly to the community from restrictive housing” in 18 months. Oregon had released another 348 people from solitary “directly to the community” in the same span.

- Over 10,000 people were released directly from solitary in 2014, according to the Marshall Project, a tally that did not include data from 26 states, the Bureau of Prisons, and immigrant detention centers.

- An estimated 61,000 individuals were in isolation in prisons in the fall of 2017, according to a survey of the 50 states, four large metro jails, Washington, D.C., and the Bureau of Prisons. Only 26 of the 56 jurisdictions surveyed reported having strict rules “to ensure offenders are not released directly into the community.”

ADX officials have told inspectors that inmates are no longer released directly from the prison. But current guards, former prisoners, attorneys, and others familiar with the process said that ADX side-steps that policy by sending prisoners for brief stopovers in solitary confinement at other facilities on their way to the streets; they can be out in a matter of weeks.

Jabbar Currence was one of them.

He saw it coming back on December 1, 2016.

Seated in what passes for a courtroom at ADX, with a shelf of generic law books against a drab concrete wall, Currence more or less predicted his future. The moment came during a deposition for a class-action lawsuit against the Bureau of Prisons, which had been going on since 2012 and came to involve 18 other inmates with severe mental illnesses. He was 36 and had been at ADX for just over nine years. He wore a plain brown smock and shackles.

Currence estimated that he’d asked the Bureau of Prisons for psychiatric treatment and therapy at least 100 times, but felt he never got much more than a brief conversation through a cell door with a shrink who acted more like a cop. He wanted help. He wanted out of ADX.

“I want to function normal,” he said. “I want to go out back in society and have a chance. I mean, I’m judging myself, but I don’t feel I’m a bad person. I don’t feel that I want to hurt people.”

His childhood was traumatic and filled with abuse and neglect in foster homes and group homes, medical records show. He dropped out of school in the sixth grade. A prison psychologist wrote: “It does not appear that the inmate has ever had a consistent or stable caregiver during his life.”

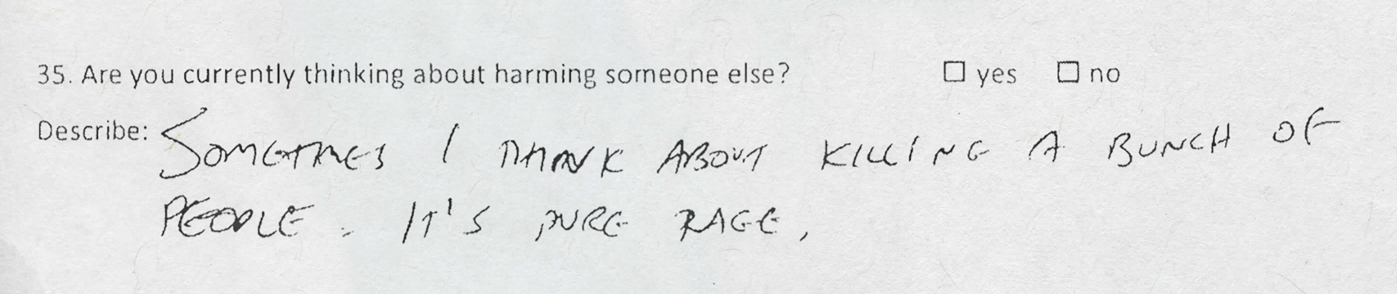

At ADX, he experienced hallucinations and delusions, including “visualizing killing and chopping up BOP staff members.” He had been diagnosed with an assortment of personality disorders and had “an extensive history of sexual deviance, including criminal charges and BOP records of several masturbatory behaviors.” He attempted suicide on multiple occasions, swallowed bits of broken metal, and harmed himself in other ways.

As he sat fighting for better mental health treatment, his release date was just over two years away.

…I know that I’ve got those risk factors there, that if I don’t get serious counseling or whatever, that I’m susceptible to go home — and I’m an extremist. I tend to alternate either things is good or things is real bad. I have a problem seeing gray areas. So I feel as if I’m not planning anything, and my plan is to go home and try to function. But I just see that moment where things could just go wrong.

By the time Currence had his deposition taken in 2016, ADX had already been cajoled through litigation into improving conditions for mentally ill prisoners. Two years prior, the BOP issued new screening procedures and guidelines, stating that “seriously mentally ill” inmates would only be placed at ADX if extraordinary security needs are identified that cannot be managed elsewhere.” The BOP said it would make exceptions when it was determined that time in ADX would “be likely to exacerbate an inmate’s mental health condition.”

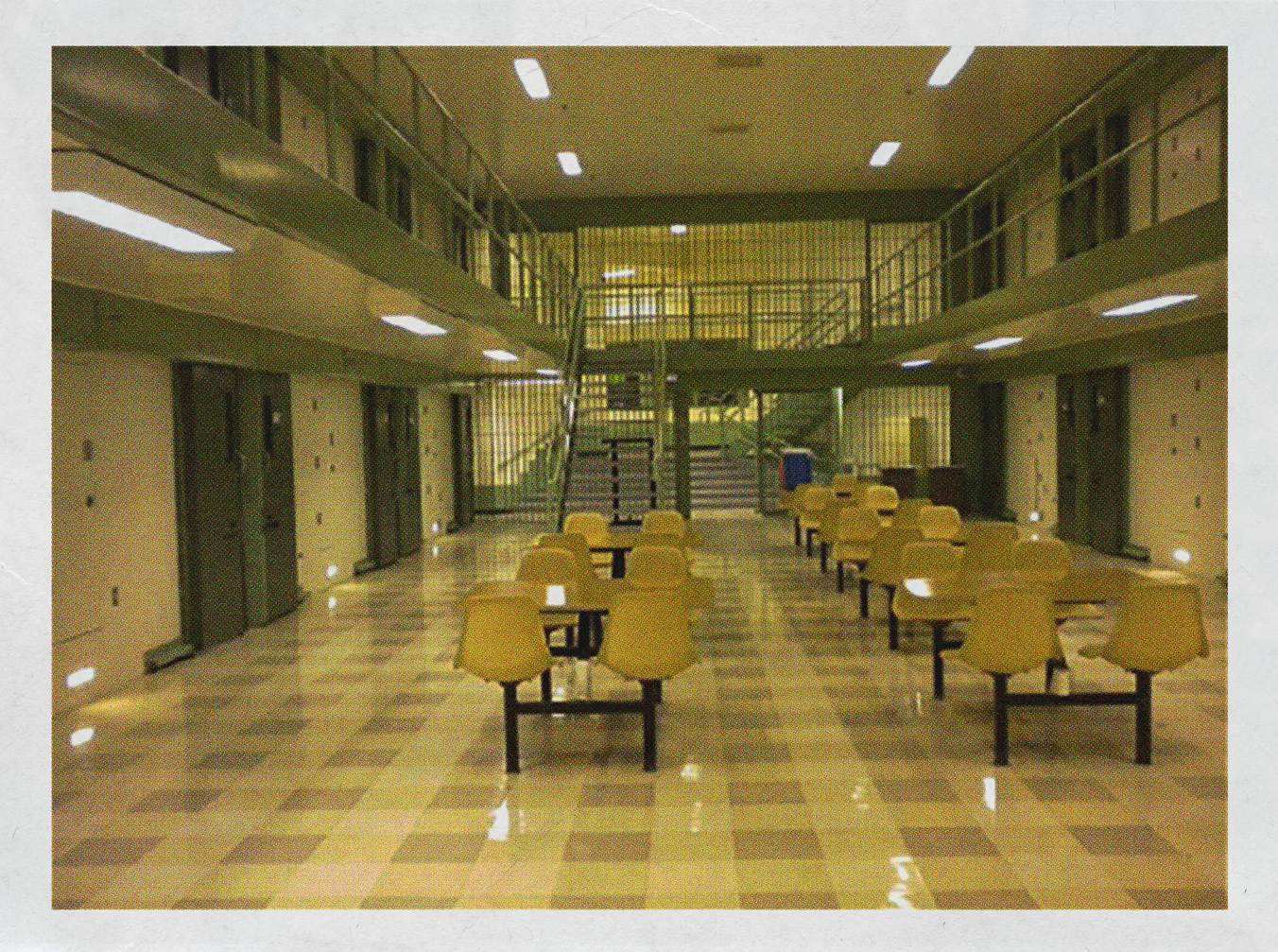

Mentally ill prisoners at ADX get “an individualized mental health treatment plan” and up to 20 hours out-of-cell time per week. In 2015, a new ADX policy mandated that inmates receive appropriate medication — which had previously been routinely withheld — and be seen by medical staff at least every 90 days. Prisoners could also get “private tele-psychiatry” on TVs in their cells, or participate in group therapy and classes while kept apart in individual phone booth–sized cages called “therapy enclosures,” which are bolted to the floor of what used to be a basketball gym.

ADX prisoners undergo periodic reviews for placement in a three-stage “Step Down Program,” which takes a minimum of 36 months to complete. It rewards good behavior with gradually increasing freedoms, starting with 10 hours a week out of the cell (but still alone in a cage) to 21 hours a week with out-of-cell interactions with other inmates in small groups. Currence says he enrolled in the step-down program early in his stay at ADX, but washed out in 2011 after a fight and never returned.

In May 2017, ADX created a “release preparation unit” for inmates with two years or less on their sentences. Participants can meet with a social worker to help get identification and Social Security cards and other bare essentials required to function in the outside world, along with guidance on how to apply for jobs and access services. One inmate told independent inspectors that the unit is “terrible,” and it reportedly “does not offer any support or resources to prepare inmates for release, and instead offers activities such as coloring books.”

Prisoners aren’t forced to participate in preparations for their release, and Currence was among those who opted out, citing a fear of being attacked by inmates he considered enemies. Other former inmates described a climate of fear and violence that discouraged participation in the step-down program.

Prisons have never been known for stellar healthcare, and ADX inmates — many of whom are there because they’re extremely difficult to handle — pose special challenges. Guards said hazards of the job include being kicked, bitten, headbutted, pelted with urine and feces, and spit on by prisoners. Sometimes they see those inmates released.

“I could have been sane or insane, they just let me walk out the door.”

Rick Arko, president of the guards union at ADX and a 21-year veteran of the institution, said there have been multiple inmates — including Currence — who he feared would go on to harm members of the public.

“When you get to know someone, you can just tell they’re going to do something bad to someone, and there’s nothing we can do to help them,” Arko said.

Arko had read a local news story about Currence’s attack on Mary in the park and said it was discussed among the ADX guards.

“There’s no shock that Currence did that,” he said. “We all knew him.”

Arko and two other guards who spoke with VICE News estimated that three or four prisoners per month are shipped out of ADX to USP Florence, a high-security penitentiary in the same federal compound as ADX, for eventual release.

ADX officials have said that releases straight from the prison do not occur, but Arko remembers at least once when it happened some years ago. Due to a paperwork snafu, the inmate, whose name Arko doesn’t recall, had been held beyond his out date. A captain at ADX told Arko to take the prisoner to the bus station. Since he was officially a free man, Arko uncuffed him and let him ride in the front seat of a prison vehicle on the way into town. The captain was livid when he found out.

“He couldn’t believe it,” Arko recalled. “I said, ‘Sir, I just put him on a Greyhound bus with women and children on it.’”

A 2014 audit of BOP data found five cases of direct inmate releases from ADX, while a 2017 report by the DOJ’s inspector general found none, though investigators noted that they looked at a small sample size.

One former prisoner, 46-year-old Mark Bundy, tells a story similar to Arko’s. Bundy says he was released directly from an ADX unit in 2009 after a 15-year sentence with the final seven in supermax. He recalled leaving with just a bus ticket, the clothes on his back, and $65 — the remaining balance on his commissary account. He took the money to Walgreens to buy a cheap cell phone and two bags of candy for the 22-hour Greyhound ride home from Pueblo, Colorado, to a halfway house in Baltimore.

“I was supposed to go to another penitentiary or something, but they never gave me no chance,” Bundy said. “They never gave me no chance to get ready for society. I walked out the ADX — they let a man come out of supermax. I could have been sane or insane, they just let me walk out the door.”

Bundy said he was sent to ADX for “harming a rat.” Most prisoners at ADX — over 90%, according to one recent estimate — are there for “disciplinary issues,” such as attacking or killing guards, staff, or inmates. Bundy’s only recollection of pre-release planning was filling out some paperwork and taking classes on the closed-circuit TV in his cell.

A spokesperson said the BOP couldn’t comment on Bundy’s case or others due to privacy restrictions, but the official policy is that released inmates are provided “suitable clothing,” transportation, and “funds to use until he or she begins to receive funds.”

Bundy now resides in West Virginia. He credits his voracious reading habit for keeping him sane in ADX and his strong support network for helping him stay afloat on the outside. He suffered a string of medical problems after prison that left him blind. He wanted people to know that despite his violent past, he doesn’t consider himself to be dangerous.

“ADX is a mental place, truthfully,” he said. “Me, myself, I went in there mentally strong and came back out of there mentally stronger. It’ll drive you crazy, if you let it.”

Currence had a darker assessment of ADX when asked in his 2016 deposition about the toll nine years there had already taken on him.

“I think it damaged me emotionally, psychologically,” he said. “Because the way I look at it, after the ADX, what’s left? It’s death row. Next is death row or the graveyard.”

He was 25 months away from going home.

“You could let me be released from the supermax straight to the streets, potentially,” he said. “Even though I’m not going to hurt nobody — but potentially putting people in danger in the community all for the sake of just holding me at the ADX?”

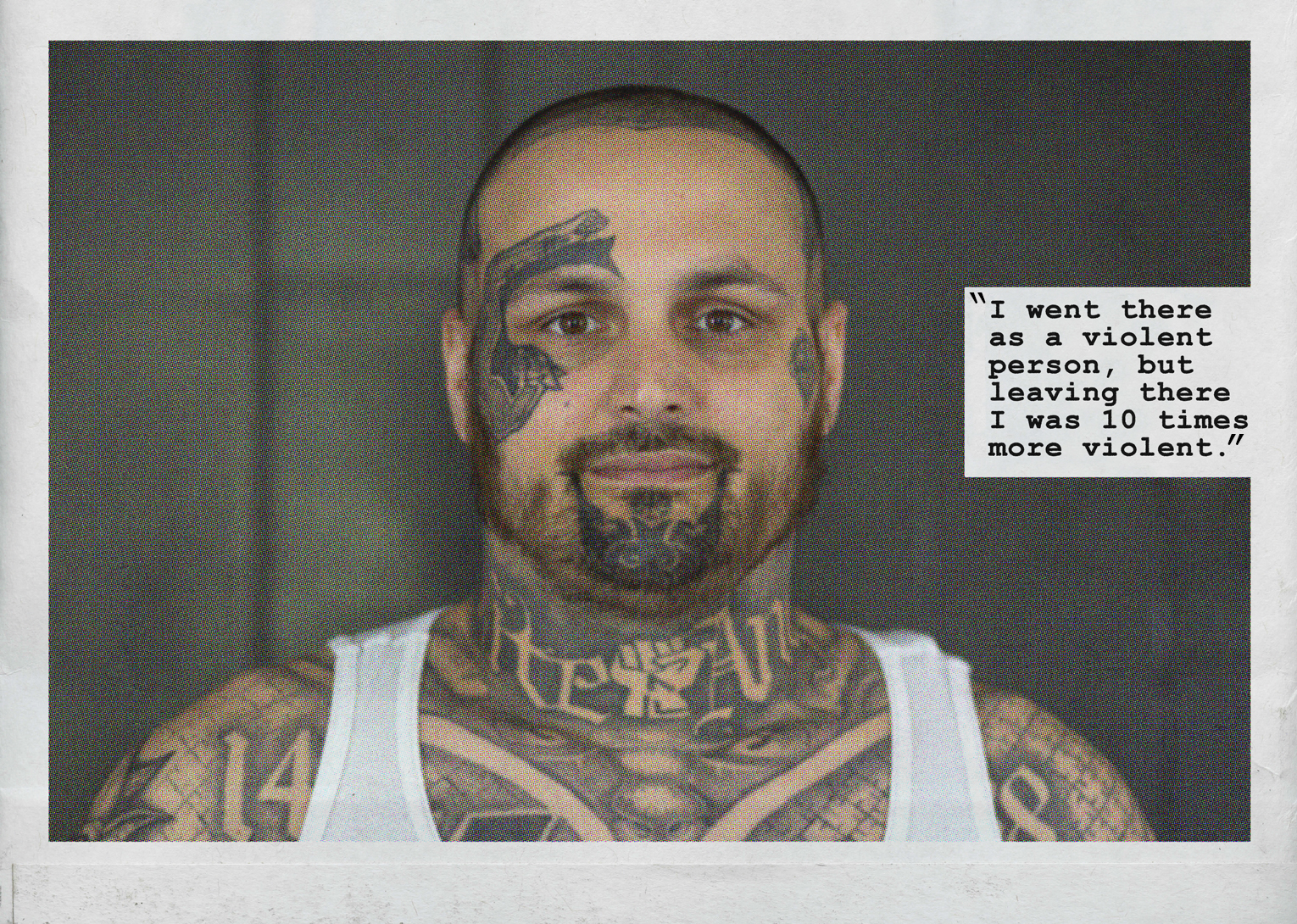

In November 2018, a few months before Currence arrived in Virginia, another former ADX prisoner named Tim Tuttamore returned to his hometown in northern Ohio. The men were not friends in prison, for obvious reasons. Currence is black; Tuttamore has the words “WHITE ANGER” tattooed in block letters across his neck with an Aryan fist in the middle.

Tuttamore, 42, used to have “Neo-Nazi” scrawled above his eyebrow, but he’s had that done over, part of an effort to get a fresh start after prison. Much of his ink remains intact. His upper torso is covered in small swastikas and white supremacist iconography, with a large Nazi SS symbol on his right pec. Tuttamore is still on probation, but he was freed from custody in March 2019 after an 18-year sentence with 12 served at ADX.

Old country songs played from a Bluetooth speaker on a cool, early-summer afternoon in his apartment in Bellevue, the sleepy Rust Belt town where he grew up. White plastic chairs stood in for living room furniture. An air mattress was on the floor in the bedroom. A food pantry schedule hung in the kitchen. He had just moved in a few weeks before, relocating from a homeless shelter in nearby Sandusky.

“I just hide out in my house all day,” he said. “It’s the Taj Mahal compared to my cell at ADX.”

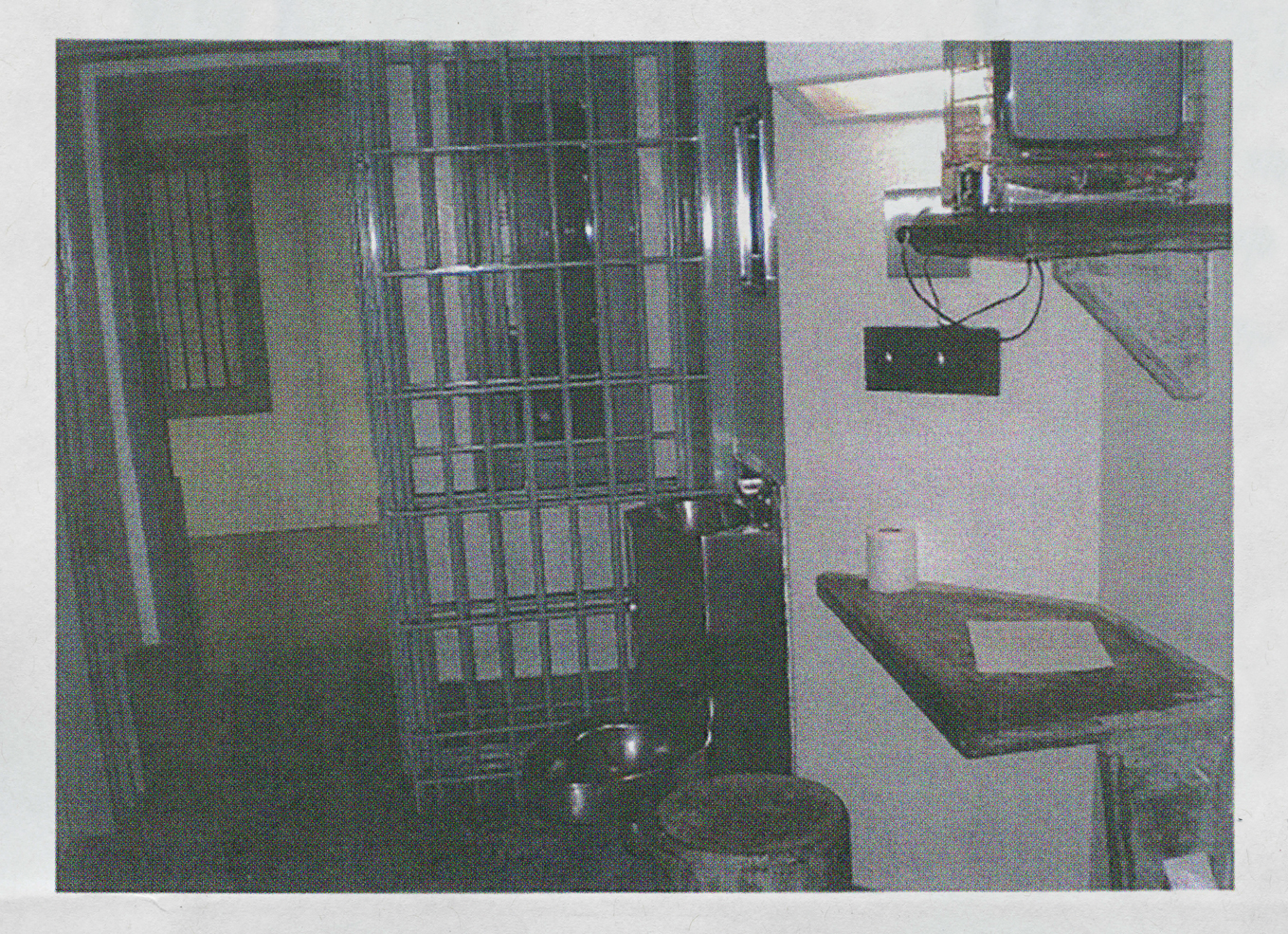

His cell was about four paces across. Most come with a tiny stainless steel shower that runs for 90 seconds when a button is pressed. There’s also a steel toilet with a sink built into the top of the tank.

Prisoners can communicate with whoever is next to them by using a toilet paper tube to blow water from the pipes, then shouting into the bowl. Tuttamore used the toilet phone to chat with his neighbor, the founder of a white supremacist gang called Soldiers of Aryan Culture. They would pass the time playing chess, each man with his own set purchased from the commissary, calling out moves through the pipes.

Tuttamore also spent hours drawing, reading books from ADX’s extensive library, exercising, and writing letters, which he signed “The Man in the Box.” Most cells come with a 13-inch color TV set, wired for 50 cable channels, but he eventually grew tired of the reruns.

The other standard furniture at ADX is a concrete desk, stool, shelf, and bed with a thin mattress. The bed has metal rings at the corners so that uncooperative prisoners can be “four-pointed” — chained down by their arms and legs. A narrow window, 42 by 4 inches, angles upward so only a sliver of sky is visible.

Each cell is equipped with double doors, one with bars, another solid steel, with slots for guards to look in, pass food trays, and shackle inmates. Aside from a few cells that face a shared common area, the prisoners in “general population” are all on the same side of the corridor, so they can’t see one another or talk across the hall.

Tuttamore remembers it being dead silent most of the time, except when the guys above or below him would freak out and start banging on the stainless steel shower walls for hours, making a loud noise that reverberated throughout his cell. Even the sound of running water in the pipes of his neighbor’s cell began to aggravate him.

“It makes you even more aggressive, more angry,” he said. “I’d get angry at the guy above me for taking a shower because it’s so noisy. You get used to hearing utter quiet. The roar of pure quiet, no sound at all. Then all of a sudden — BANG BANG BANG! They start kicking the shower. It’s like, ‘Motherfucker! This guy must think I’m weak!’ It breaks you down.”

Tuttamore called himself an “independent skinhead” with no affiliation to any specific prison gang. He arrived at ADX in 2005 because he had repeatedly attacked other inmates and was considered a leader among the white supremacist gangs at a high-security penitentiary in Terre Haute, Indiana. He was an enforcer who wouldn’t tolerate certain people on the rec yard.

“If somebody was a child molester, I’d hurt ’em,” he said. “If somebody was a rapist, I’d hurt ’em. If somebody was trying to bully another person who didn’t deserve to be bullied, I’d hurt ’em. That’s how I rolled.”

He was sent to the hole in Terre Haute for nearly beating a member of the Latin Kings gang to death with a padlock clipped to the end of a belt. He said the attack was motivated by the man — nicknamed Mountain — attempting to rape a smaller, younger inmate. While in the hole, Tuttamore used his bare hands to pummel another inmate he suspected of snitching.

Inmates have been housed in individual cells since ADX opened in 1994, but groups were initially allowed to congregate in an outdoor rec yard surrounded by high concrete walls. That freedom went away in 2005, the year Tuttamore arrived, when two men were murdered in separate incidents, including one in an alleged Mexican Mafia hit. Most inmates now get their fresh air in metal cages, which some call “dog kennels.” Tuttamore recalled being brought into one on his first day and thinking: “Welcome to the home of the killers.”

ADX inmates used to be able to purchase photos of themselves to send to loved ones, and Tuttamore has several. In one, he holds his fists in a boxer’s pose. Looking back, he can see the rage that used to boil inside of him. He’d been in and out of prison his entire adult life, first in a Texas state pen, where he became radicalized as a skinhead, then in the federal system for a series of bank robberies.

Tuttamore was miserable at ADX. He developed a painful lump on one of his testicles that went untreated for months. He sued the BOP to undergo surgery, and after the benign growth was removed, a guard started calling him “One Nut Tutt.” The fury burned him up until one day in the dog kennels, he realized he was surrounded by gang leaders doing life. He was the only one with a release date.

“I realized I didn’t want to live that life,” he recalled. “There’s guys that did 30 years in ADX. I don’t want to be in a concrete tomb until my heart stops beating.”

Tuttamore, Currence, and others at ADX have few options for getting out. Escape is not one of them. Even if somebody were to somehow make it out of a cell, the prison is designed to disorient inmates, with corridors blocked by remote-controlled steel doors. ADX is also a prison within a prison. There are three other federal facilities in the same complex, which is surrounded by gun towers and layers of fencing.

The only things nearby are a golf course, the sleepy mining town of Florence (pop. 3,914), and miles of scrub brush on a plateau surrounded by snow-capped Rocky Mountain peaks. Denver is a two-hour drive north.

“They designed it the right way,” Tuttamore said. “They couldn’t have put it in a better place and couldn’t have come up with a better scheme to keep people from getting out.”

Many prisoners comment on the emotional impact of losing sight of the mountains when they enter the prison. Ray Luc Levasseur, a 72-year-old leftist radical who participated in a series of bombings in the early 1980s, was among the first prisoners placed in ADX when it opened, arriving in February 1995. He said it felt like going underground.

“I love mountains,” Levasseur said. “You’re surrounded by them, you get that last look at the power and beauty of this Earth we’re all inhabiting, and then boom, it’s gone.”

Levasseur did 13 years in solitary, including four at ADX. Paroled in 2004, he lives in rural Maine, where he’s an anti-prison activist and author. Prior to ADX, he was held at the U.S. penitentiary in Marion, Illinois, which was the successor to the original supermax: Alcatraz. All inmates at Alcatraz had individual cells, but they weren’t totally isolated unless they were being punished in the hole. Likewise, inmates at Marion were also allowed limited interaction — until two guards were murdered on the same day in 1983 by Aryan Brotherhood members.

After the twin killings, Marion went on near-24/7 lockdown and the BOP began designing ADX, a new American experiment with isolation. One Marion guard killer, Tommy Silverstein, went on to do 14 years at ADX until his death in May. He was housed in a special unit deep in the bowels of the prison known as Range 13, where he went weeks with minimal human interaction or outdoor exercise, despite exemplary behavior later in his life.

Prolonged solitary confinement began in the U.S. in the 1800s, when New England prison reformists sought new ways to rehabilitate criminals. Distinguished guests were invited to come observe “The Philadelphia System,” and they were appalled by what they witnessed. Charles Dickens wrote of one inmate in 1842: “He is a man buried alive … dead to everything but torturing anxieties and horrible despair.”

Solitary largely fell out of favor until the ’80s, when crime went up, harsh sentencing laws took effect, and prisons became overcrowded. By the time Alcatraz closed in 1963 and ADX opened in 1994, the U.S. prison population shot up 1,100%, from around 88,000 state and federal inmates to over 1 million. The incarceration rate went from 46.8 to 387 per 100,000 people.

In many places isolation is now the de facto way to deal with unruly inmates and those with mental illness. According to a 2016 Amnesty International report, “more than 40 U.S. states are believed to operate super-maximum security’ units or prisons.” Studies indicate that young people, people of color, and the mentally ill are held in solitary at higher rates than other prisoners.

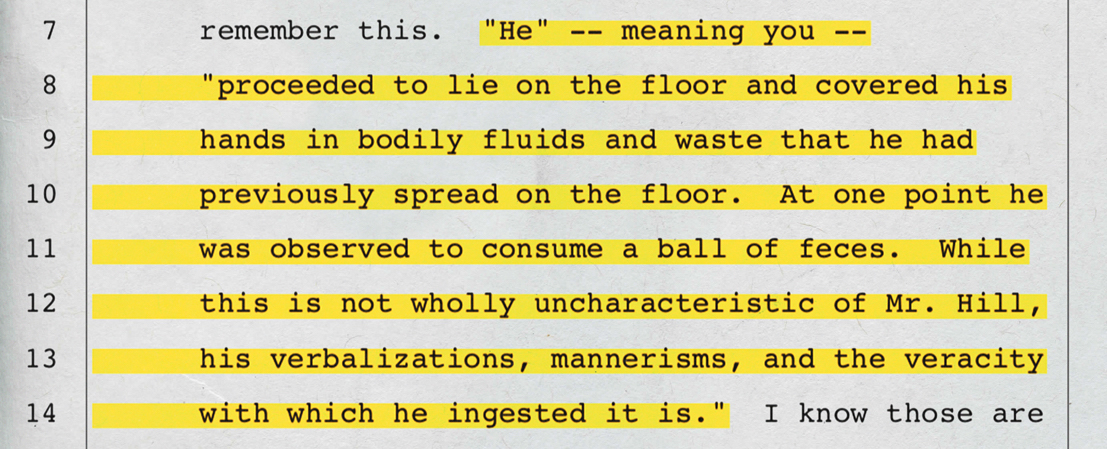

Bob Hood, the warden at ADX from 2002 to 2005, describes it as “the ultimate prison if you’re looking for security.” But he also saw desperate inmates lash out for human contact. He recalled one man who smashed a shampoo bottle and shoved a plastic splinter into his penis so he could go to the hospital and interact with doctors and nurses.

“Let’s be honest, it has nothing to do with rehabilitation,” Hood said. “These are not the 95% that are going to be released and will be your neighbors.

While some high-profile prisoners serve almost their entire sentence at ADX, regular inmates can be transferred out to finish their time in another facility. One way for that to happen is through the prison’s “Step Down Program.” It begins with guys who have shown good behavior being transferred into “Joker Unit.”

Joker Unit has 32 cells that face a common area with showers. It’s usually the first time that inmates are able to interact with each other without restraints, and it can be a harrowing experience. As Tuttamore put it, “It’s like taking a bunch of beaten and abused pit bulls from a cage and putting them into a pod and seeing what’s going to happen.”

Tuttamore said he saw a 68-year-old inmate getting bullied by a younger man in the program and decided to intervene. “I ended up smashing that dude with a boomstick and put 38 staples in his face,” he said.

Last September, an inmate in Joker Unit was sentenced to an extra three years in prison after he was caught with a 4.5-inch shank “hidden in his rectum” and a 1.5-inch weapon “resembling a razor blade” inside his cell.

Another former ADX inmate, Ismail Royer, said he witnessed two attempted murders in the step-down program that were “just the most brutal things I’ve ever seen in prison.” Royer, who was convicted of helping friends reach a militant training camp in Kashmir after 9/11, was released in 2016. He now works for a think tank in Washington, D.C., where he promotes peace between religions. Every time the cell doors would open, he recalled, he was prepared to fight for his life.

“You’d have anxiety about being asleep,” Royer said. “It was just constant fear of your life. When I got there, the first thing one guy told me was ‘Not every day is promised.’”

Prisoners who “demonstrate periods of clear conduct and positive institutional adjustment” are transferred to units with gradually more freedom in USP Florence, the adjacent high-security penitentiary. The process takes a minimum of 36 months to complete. Eventually, they are allowed to eat and exercise in small groups, and spend nearly 25 hours per week out of their cells.

“I went there as a violent person, but leaving there I was 10 times more violent.”

Several ex-inmates felt like it was impossible to complete the process. Royer compared it to “Sisyphus pushing a rock up the hill” because every time he’d get close to the final stage, he’d get hit with a minor disciplinary infraction, like an out of place item in his cell.

The officer in charge of ADX’s general population units testified in 2017 that transfers through the first and second stages of the step-down program were up 59% and 135%, respectively, since October 2009. But Tuttamore had a similarly frustrating experience.

“They didn’t want certain people to leave,” he said, “so they would set shit up or just blatantly refuse to let them leave and start them at the beginning of the program all over again.”

Tuttamore was eventually transferred to a high-security penitentiary in Kentucky in December 2016, after he was identified as having a serious mental illness during a lawsuit against the BOP. He stayed at the other prison for about a year and a half. Roughly three months before he was due to be sent home to Ohio, he attacked another inmate who he suspected of stealing, bludgeoning the man in the back of the head with padlocks on a belt. He believes his time at ADX only made him more aggressive and did nothing to prepare him for his eventual freedom.

“I went there as a violent person, but leaving there I was 10 times more violent,” he said. “There’s no rehabilitation. None. They got all these stupid little courses you take. They’re meaningless. It doesn’t help you. It doesn’t help when you get out of prison.”

Tuttamore spent a few months in a halfway house starting in November 2018, but was sent to the local jail after he was accused of smoking K2, or synthetic marijuana. He says his erratic behavior was part of his struggle to readjust to life on the outside: “I’d get sick just being around people. I’d just ball up and shake.”

After Tuttamore was released from jail in late March, he ended up in a homeless shelter, which he said “did more for me in three days than the halfway house did in three months.” A local non-profit got him housing. His tattoos and criminal record have made finding a job next to impossible, so he’s putting to use a skill he honed in prison. He acquired a tattoo machine and has been offering body art in exchange for assistance from friends and family members.

Tuttamore’s brother and family are helping him out, and he’s reconnected with his 22-year-old son. He desperately wants to avoid going back to prison, but he knows anything can happen. He rides a bike around town because he’s afraid of driving.

“If a cop pulls me over and runs my plates, it comes up ‘Tim Tuttamore, armed bank robber, violent felon, leader of the skinheads of America,’” he said. “That is not a cool resume, dude. Clearly, I’m getting out of the car at gunpoint.”

Ed Aro couldn’t believe what he was seeing. It was 2011 and the lawyer was peering into the darkest depths of the ADX.

“There was a particular area in the disciplinary housing unit at the ADX that people at that time called the SHU,” Aro, who is based in Denver, said. “That was mostly inhabited by the lowest of the damned. They were highly dysfunctional and many of them profoundly mentally ill.”

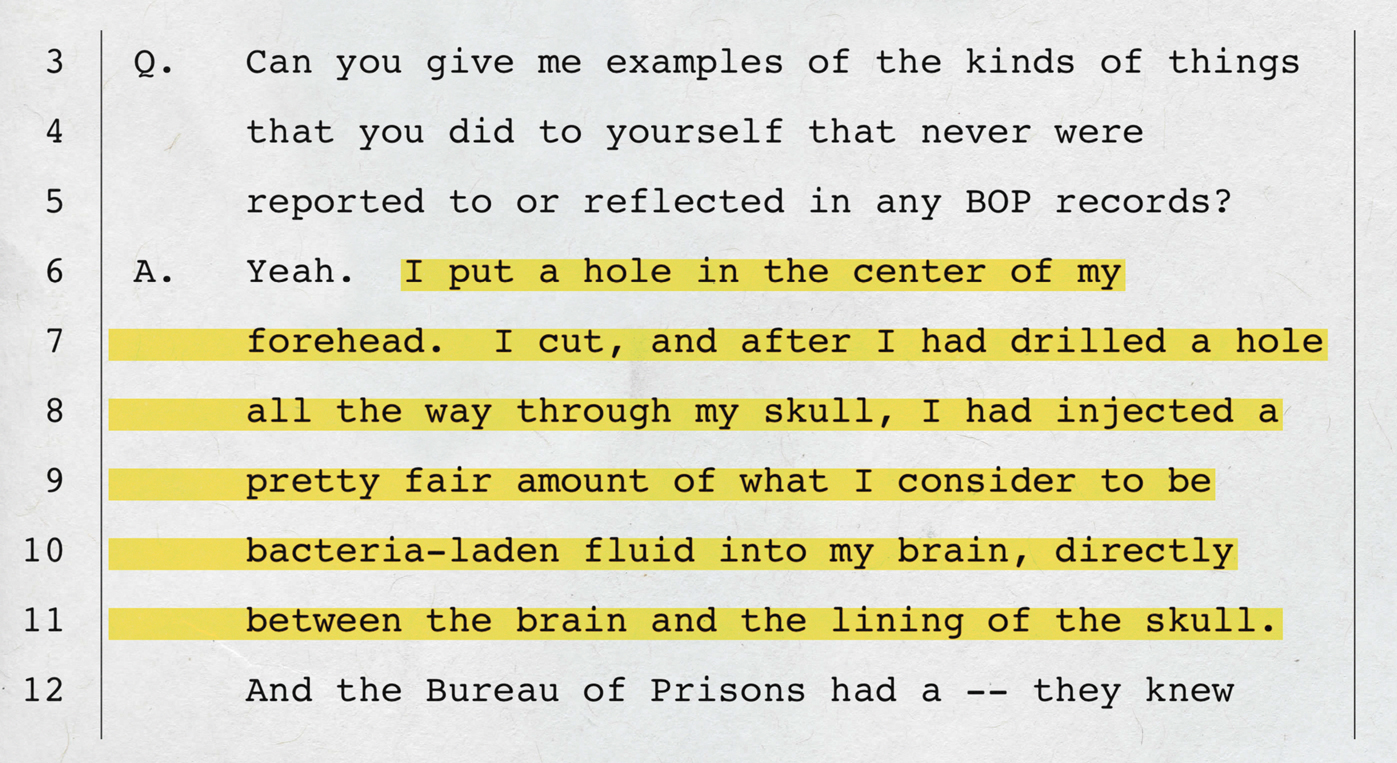

He met a man named John Jay Powers who “essentially destroyed his own body” over years. Powers cut off both his pinkies, his ear lobes, and his Achilles tendon, removed one of his testicles, drilled a hole in his skull, pushed pieces of metal into his brain, and tattooed his entire body with what he called “Avatar stripes” using a razor blade and black dust from carbon paper. (Powers is now in a high-security mental health unit in Pennsylvania; he’s scheduled for release in 2022.)

“There were inmates who spent months or years in a catatonic state covered with their own body waste sleeping on bare concrete surfaces with no blankets,” Aro said. “Some came very close to dying from malnutrition because food was being withheld from them. Folks were chained down hand and foot on a concrete bed for up to 30 days at a time — just really medieval, crazy behavior.”

Such treatment of ADX inmates was disputed in court filings by the BOP, which pushed back against Aro’s “inflammatory descriptions of some behavior of inmates” and “scandalous allegations.” Aro maintained that his claims were supported by medical records and testimony from prisoners.

“The Bureau expects all staff to communicate with everyone in a positive and effective manner,” a BOP spokesperson said in response to questions about mistreatment of inmates at ADX. “The Bureau also expects staff to treat everyone with dignity and respect. Accordingly, allegations of staff misconduct are investigated and appropriately addressed when they are made.”

The SHU is where Aro met Jabbar Currence.

In October 2009 the Washington Lawyers Committee, a non-profit in D.C., received a letter from a mentally ill ADX inmate pleading for help. They eventually contacted Aro’s high-powered corporate firm, Arnold & Porter, which takes on pro bono litigation, to help sue the BOP for violating the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on “cruel and unusual punishment.”

Currence would come to take on a key role in the case as both a plaintiff and witness. On September 7, 2013, an inmate named Robert Gerald Knott, who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia and “severe psychotic illness,” hanged himself in a cell next to Currence. Knott, 48, was usually quiet, but he had been screaming and babbling incoherently for a week, Currence said. Rather than offering help, Currence saw guards “peeking in his cell and whispering to each other like he was some sort of spectacle.”

The day after Knott’s suicide, Currence wrote a letter to Aro — later published by The Atlantic — describing what he saw in the aftermath of the suicide, one of 10 at ADX since 1994:

Food was scattered all over the cell. The drawings were of naked women, with toothpaste in the shower, the word ‘heaven’ written on the wall. Ed I have seen a lot. But you are never prepared to see any human being fall into such a state of mental illness that he or she is forced to do the irreversible. Especially when you witness it play out before your eyes day by day.

Over the next five years, Aro got to know dozens of inmates at ADX, including several who were eventually released. Currence was always polite and friendly during their interactions, but he was among the most difficult to deal with for prison staff. He frequently exposed himself and masturbated in front of female nurses and guards at ADX. Currence estimated that he was placed on suicide watch over 45 times.

“He is a profoundly lonely person who sometimes provokes confrontations with staff members because otherwise he’s just by himself, and at least if he’s being handcuffed or dragged out of his cell he has contact with people,” Aro said. “That sounds crazy to anybody who’s not familiar with this environment, but when you have the sort of scrambled wires that Jabbar Currence has, and have lived in the incredibly deprived circumstances he’s lived in for a really long time, what is not normal becomes normal.”

Beyond the grim mental health situation at ADX, Aro was startled to learn how prisoners were being released when he first took the case. Around 2011 and 2012, “virtually everyone,” he said, went “either directly to the street or to a very short-term stay in a penitentiary discipline unit before going straight to the street.”

One prisoner named Rodney Jones was freed in October 2011 after a 13-year sentence with eight served at ADX. He had been in and out of mental hospitals and prisons his entire life, and was sent to supermax after repeatedly assaulting other inmates and throwing urine on a guard.

Jones did not do well in isolation. He cut himself and hoarded his medications, taking it all at once to overdose. He honed his body into a weapon, doing up to 3,000 push-ups per day in his cell. But as his release date from ADX approached, he decided he didn’t want to leave.

“I asked the warden, ‘Can I stay in?’ He said, ‘No, we can’t keep you here.’ There was no way I could do anything else to get him to keep me,” Jones recalled. “I was petrified. I didn’t know what I was going out to. I was afraid to the point I tried to kill myself.”

The suicide attempt was serious enough that he was sent to a hospital outside the prison, where he stayed for a week. He returned to ADX three days prior to his scheduled release and spent his last days there in the SHU disciplinary unit.

When the time came to go home, Jones was escorted from his cell just after breakfast. With shackles on his ankles and wrists and a “belly chain” restraint around his waist, he was loaded into a van with armed guards and driven from Colorado to a transfer point for federal prisoners in Oklahoma City. From there, he was flown to another prison in Maryland. After another van ride, again in full shackles, he was dropped off at around 9 p.m. at Union Station in Washington, D.C. He had $9 in his pocket and no clue how to function in the free world.

Jones said if his brothers hadn’t been waiting to pick him up, “I probably would have done something to go right back” to prison. Upon his arrival home, he learned his father had passed away a few weeks prior. Everyone in his family had been afraid to deliver the news while he was in ADX. When he woke up on his first morning out, he forgot that he could leave his bedroom and sat waiting for his mother to open the door and bring him breakfast.

“I knocked on the door looking for somebody to come open it,” he recalled. “I went upstairs and asked my mom ‘Can I use the bathroom?’ She’s like ‘What? Boy, you home, stop acting like you in prison, you know where the bathroom is.’ I was so used to asking to do everything. I kept asking, ‘When we gonna eat, when we gonna do this?’”

He slipped back into his old ways and began selling synthetic marijuana on the streets of D.C. In 2015, he was interviewed for a New York Times Magazine story headlined, “Inside America’s Toughest Prison.” The writer described Jones as feeling “like Rip Van Winkle” because so much had changed while was away at ADX. Finding work became even more difficult. When Jones applied for a job stocking shelves on the graveyard shift at Safeway, the manager had read the article and refused to hire him.

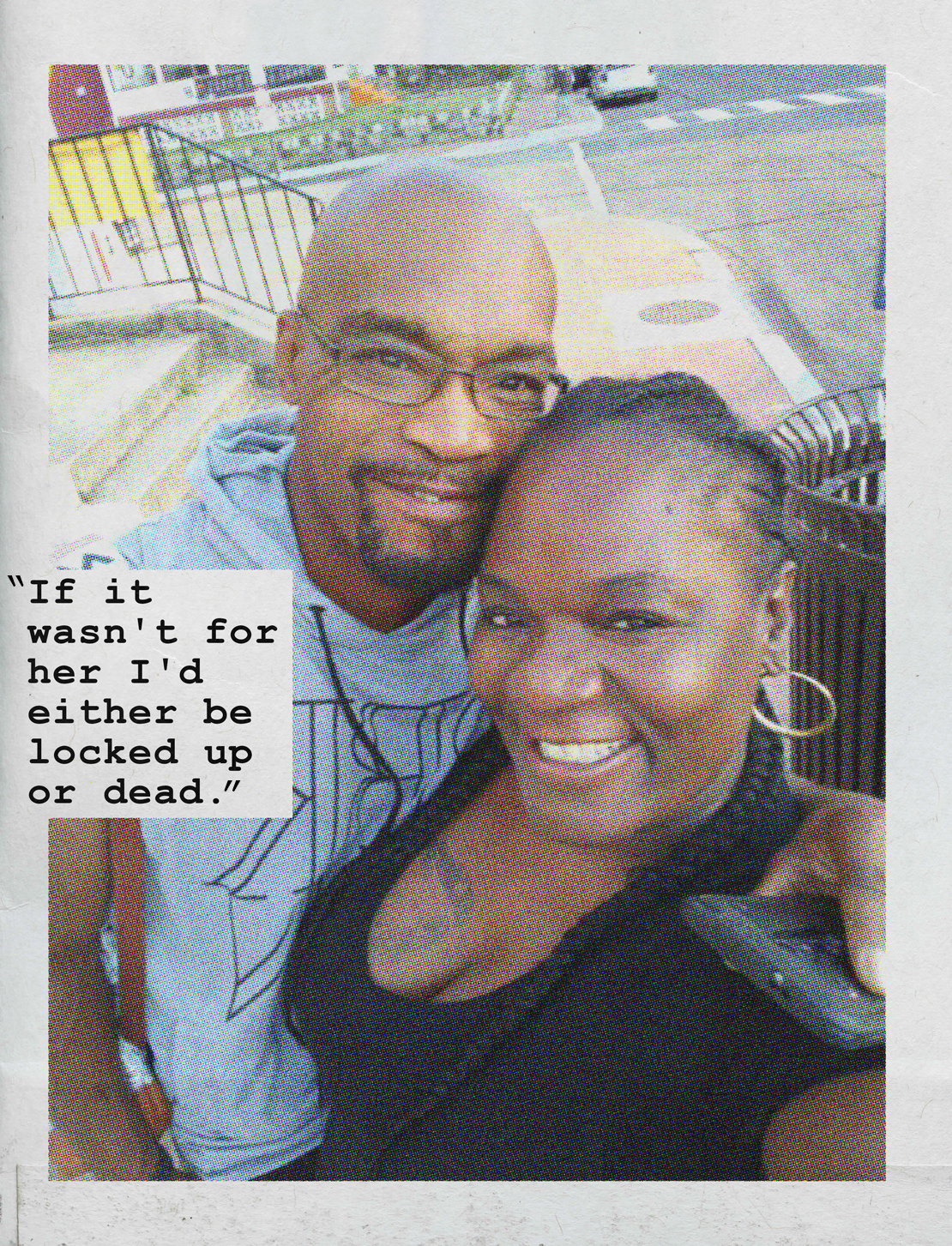

Now 51, Jones lives in suburban Maryland, where he works construction. He credits his wife Lisa, a woman he’s known since childhood, for saving him from going back to prison.

“She’s been my rock,” Jones said. “She’s basically the one that kept me afloat. She pulled me out. She seen the road I was heading down, she seen the trouble I was getting into, and she pulled me up out of that.”

Jones also had support from Aro, who bought him a jacket and boots during his first days on the streets, and another attorney who once talked him off the D.C. metro tracks. Aro has offered assistance to others in various ways, including paying for transitional housing to keep one from being homeless. Aro said he also tried to help Currence, but he became frustrated “because we couldn’t keep him focused on helping himself.”

Aro and the ADX inmates eventually settled their lawsuit against the BOP, reaching a deal in 2016 that requires independent monitors to inspect ADX twice a year to ensure that conditions at the prison continue to improve. (Aro’s law firm was also awarded over $3 million, which will fund future pro bono litigation; the prisoners received no damages or financial compensation.)

Aro said the BOP now tries to avoid hard exits for ADX inmates, but Currence was among those who declined to take advantage of the pre-release services. The lawyer is no cheerleader for the BOP, but he doesn’t blame the government for what happened during the incident in the park with Mary.

“I don’t know that there’s anything that I or anybody at the BOP could have done differently,” Aro said, “and so I don’t mean to fault anybody in that process other than Jabbar for making whatever decisions led to this situation.”

Currence doesn’t see it quite that way.

He was afraid there had been some kind of mixup. They would probably be coming back for him any minute. It was February, 5, 2019 and Jabbar Currence was a free man for the first time in nearly two decades.

“I couldn’t envision that in three days that it would all be over again — it never entered my mind,” he said. “It was like a truck just hit me from out of nowhere and things just went horribly wrong.”

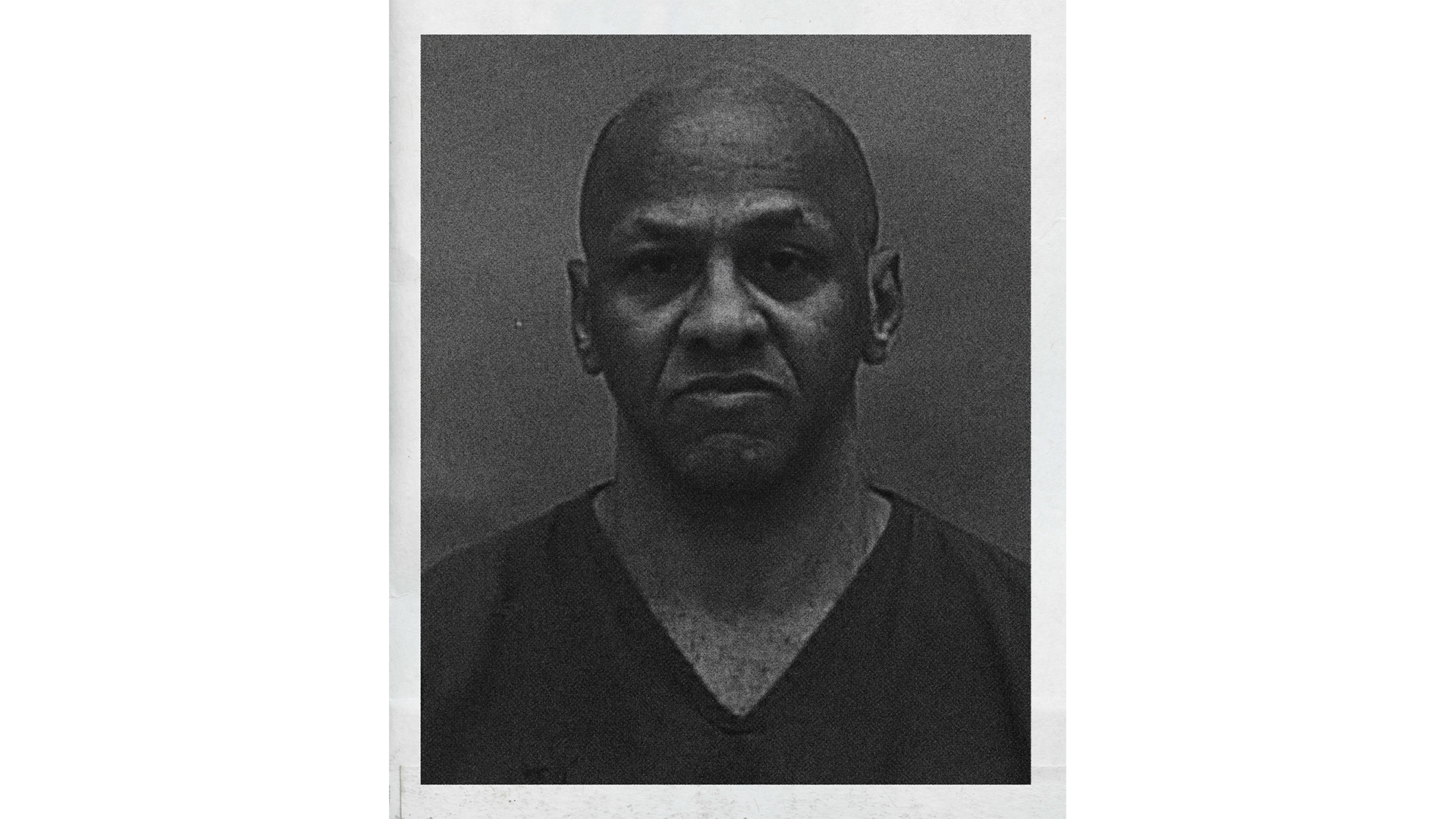

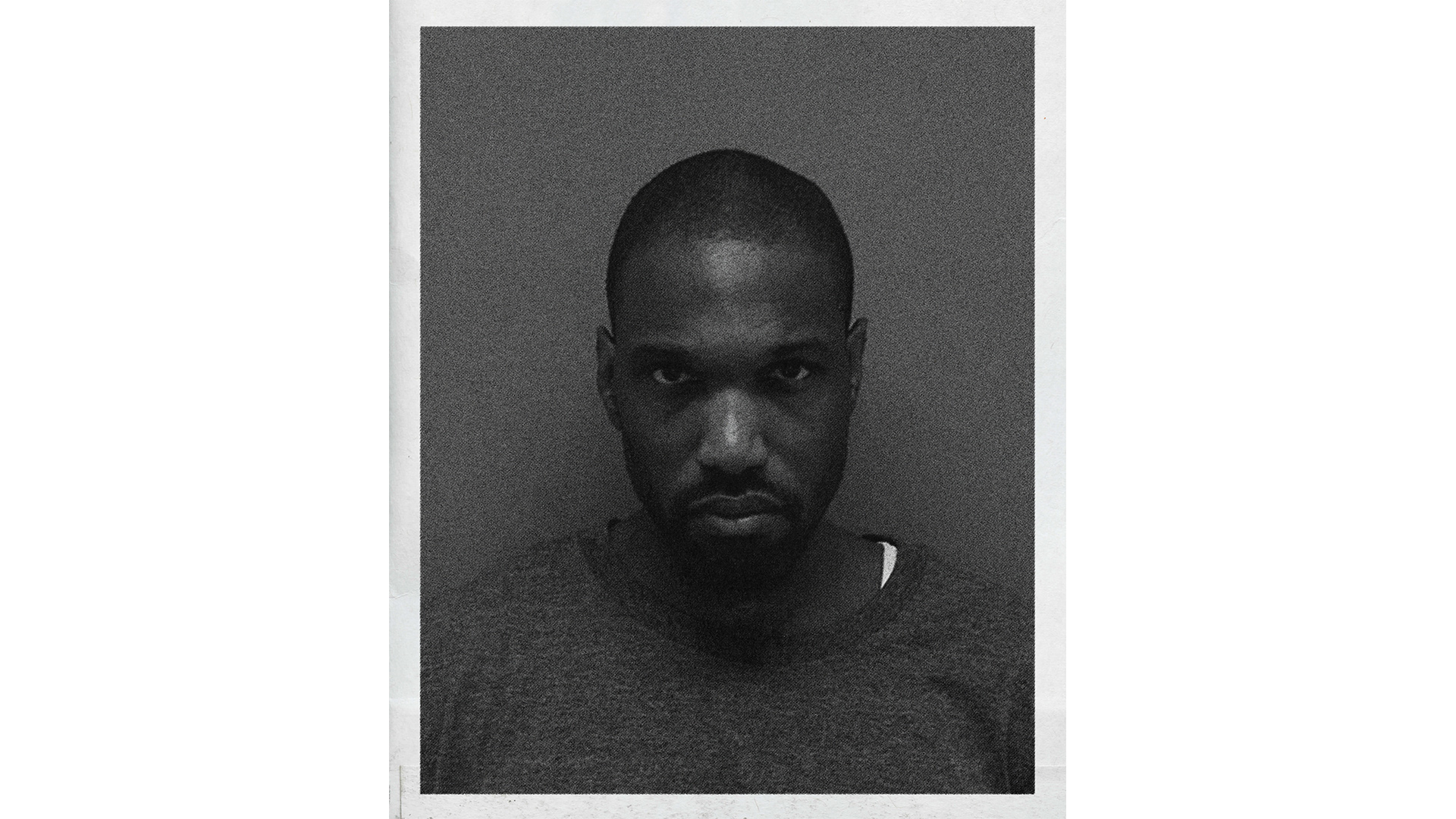

Currence recalled his few days out of prison while seated on a metal stool in the visitation area of the Hampton Roads Regional Jail in Portsmouth, Virginia. He still couldn’t quite wrap his head around how ended up back in shackles. Flecks of silver had crept into his hair and beard since his deposition with Aro two years ago at ADX. His red smock signaled that he was on “restricted status” at the jail — meaning he was back in solitary.

He said his journey home to Virginia began in late December when he was transferred out of ADX to the penitentiary in the same complex. After a brief stopover in Oklahoma City, he was taken to a high-security federal pen in Atlanta, where he stayed for almost a month. He was briefly assigned a cellmate, but said the man protested and was moved elsewhere after a day or two. In early February, he was shipped to another federal prison in Lee County, Virginia, and from there it was a seven-hour drive to Newport News.

He said he was shackled in a van with armed U.S. Marshals, and he wore a “shock sleeve” taser around his forearm capable of delivering several thousand volts if he misbehaved. They didn’t stop for bathroom breaks, and Currence said his escorts didn’t speak to him until they arrived at the halfway house parking lot and removed his restraints.

“I heard one of ‘em say that, ‘This ain’t nothing but a set-up for failure,’’ Currence recalled. “What was going through my head was basically, ‘Am I really free? This so surreal right now. Like, I just did almost 19 years in federal prison. This has gotta be a mistake.’”

The transfers allow the BOP to say Currence was not released directly from ADX, but he thinks that is splitting hairs. (A staff psychologist at ADX agreed, telling investigators in 2017 that similar inmate transfers were “no different” than direct releases.)

“Technically, they can say they’re not releasing me from the supermax, but virtually I was in solitary confinement that whole time through the course of that,” Currence said. “I was released to the federal halfway house with no nothing — $21 is what they gave me.”

After getting settled in the halfway house, he finally began to enjoy the moment: “It was just a beautiful feeling. I couldn’t believe that I was out.”

“Nobody is preparing any of these people. It’s shocking. You’re too dangerous to be anywhere else but we’re going to release them to the community? Are you kidding me?”

The next day, he went to a Walmart and realized how much the world had changed in the years he’d been away. With everyone looking at their phones, he felt like nobody made eye contact anymore. He was flummoxed by self-checkout.

Currence said on the morning before he was arrested for attacking Mary, he awoke and bathed himself “meticulously” before heading out for a doctor’s appointment. When we met in person he wouldn’t get into specifics about what happened that afternoon, but in a previous phone call from jail he said he “got ahold of some Spice,” another name for synthetic marijuana. According to the police, he “attempted to masturbate in front of two nurses” in the hospital. Then he approached Mary and asked to borrow her lighter.

After the incident, she said, employees were temporarily instructed to use a buddy system when going outside. She no longer smokes in the park. She still wants answers about how and why Currence was let loose from supermax.

“It’s not just a question of how it affects him and the justice system or even me,” Mary said. “This is something that affected a health care institution. This affects families — I was laying on that freaking ground with his hands around my neck thinking I was going to die and never see my two kids again.”

The way Currence sees it, “the system failed me.” In reality, he and the system probably failed each other.

Looking back, there were numerous times when his life could have taken a different trajectory. When he first arrived at ADX in 2008, he was “young and dumb,” and excited about the prospect of being around legendary criminals like Wayne “Silk” Perry, a feared hitman from Washington, D.C. Then after a few months, he remembers saying to himself, “Oh man, maybe this is a little bit more than you bargained for.”

After getting kicked out of the step-down program for fighting in 2011, he often found himself in the disciplinary unit and life in supermax became an endless downward spiral of acting out and being punished.

“I would jump off the sinks, I would ram my head into the walls,” he said. “I would break the sprinkler and swallow the metal bits off the sprinkler. I would do all types of stuff like that.”

He chose not to enroll in the new ADX pre-release unit because he had less time left on his sentence than some other inmates, and he felt that meant the others had less to lose if a fight broke out. But even if he’d decided to take the risk, there’s no guarantee it would have made a difference. Other inmates left ADX under better circumstances and still failed.

Ernest Shaifer, the man now serving 30 years in Florida for brutally assaulting two women, was so excited about his freedom that he allowed a CNN film crew to follow him around during his first days out. The footage never aired. Shaifer’s dad found him a nice place to live and a steady job detailing cars, but within a year he found himself strung out in a crack house, covered in blood, being ordered to the floor at gunpoint by cops.

In a letter from prison, Shaifer, 56, told me came out of ADX in bad shape mentally. He was among the plaintiffs in the SHU unit from Aro’s lawsuit, and he only had two months at a high-security penitentiary before hitting the street. “I believe my stay at ADX contributed greatly to my recidivism,” he wrote. “I was not prepared for reacclimating to society.”

His 86-year-old father, Carl Shaifer, said there’s not much he could have done differently for his son: “He had more than most people that get out of jail … He made money, he got a job, he had a truck and a nice place to say, but he was just insane.”

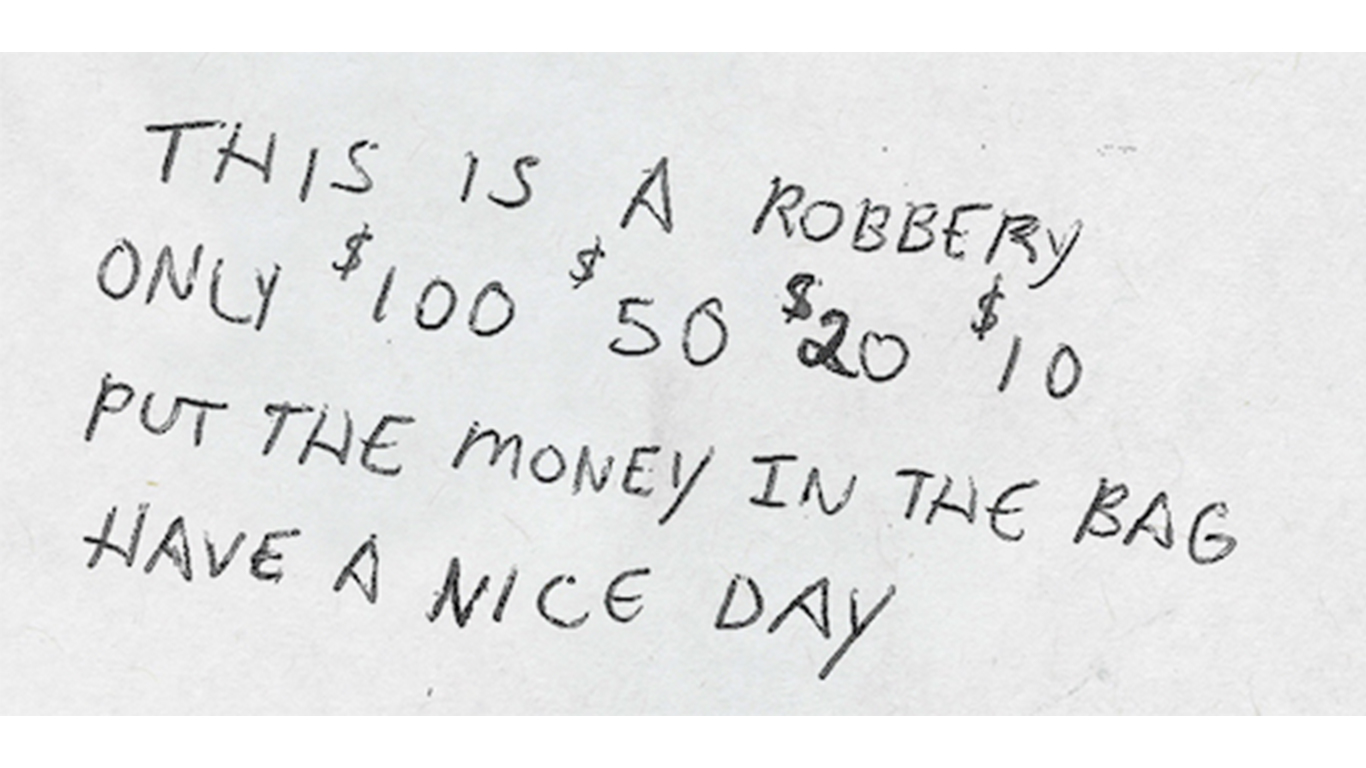

Mario Holmes had stable housing with his mother and was on medication for schizophrenia when he robbed a bank in Kansas City last July. He was unarmed during the heist and handed the bank teller a note that said “This is a robbery. Only $100, $50, $20, $10. Have a nice day.” He walked out with about $3,000 and was arrested without incident at a shoe store down the street from the bank.

Holmes’ mom, Valerie McCraney, said her son believed that the BOP had placed cameras in his eyes and microphones in his ears, and the only way to get them out was to commit a robbery and return to prison. “He absolutely believed what he was doing was the right thing to do,” she said. “All I could say to him was ‘Mario that’s not right. If you leave, I can’t do anything but call the authorities.’”

Antoine Bruce, 35, went from ADX to six months in a BOP program called STAGES (Steps Toward Awareness, Growth, and Emotional Strength), designed for prisoners who “have a chronic history of self-injurious behavior or do not function effectively in a prison setting.” The program has around 30 beds, and inmates must opt-in after they are flagged based on their behavior and medical history. The BOP said the program, launched in 2014, has been “incredibly successful” and “prepares inmates for transition to less secure prison settings and for successful reentry into society.”

But Bruce seemingly received less support after he was free than while he was behind bars.

Bruce declined an interview request, but Phil Fornaci, an attorney formerly with the Washington Lawyers Committee, the group that initially launched the mental health lawsuit with Aro, knew Bruce well and met with him several times after he got home to Washington, D.C. Fornaci said Bruce “didn’t last” in his halfway house, and the BOP arranged for him to get a bed in a D.C. homeless shelter, which is where he was arrested for the alleged knife fight.

Fornaci called Bruce “extremely polite” and “smart as hell,” but said he was doomed by his circumstances. One day Bruce was in Fornaci’s office charming the receptionist, the next he was calling from jail.

“He left me a voicemail message saying he’d gotten in a fight and a knife was involved. It was so horrible,” Fornaci said. “Nobody is preparing any of these people. It’s shocking. You’re too dangerous to be anywhere else but we’re going to release them to the community? Are you kidding me?”

The BOP does not release data about recidivism among former ADX inmates, but the rate is high across the federal prison system. About half of federal offenders were rearrested over an eight-year period, according to the U.S. Sentencing Commission.

There are numerous studies that suggest prisoners who spend time in solitary are more likely to reoffend than those who don’t. Not every former ADX inmate is like Currence — many have gone on to lead productive, law-abiding lives. But Currence believes he came out of ADX a more dangerous person than when he went in.

“It made me not want to be around people,” he said. “It made me more angry. It made me more resentful. It made me more thoughtful. I think it made me more of a predator. Well, not predator in the sense that — it just made me angry. Real angry.”

About a week before our interview, Currence was abruptly transferred from the Hampton Roads Regional Jail to a state mental hospital in Petersburg, Virginia. Speaking by phone from the hospital, he explained that he’d been having issues at the jail. He fought with other inmates and was placed in solitary. After that, he picked up where he left off at ADX.

“Basically, I was on suicide watch,” he said. “I tied stuff around my neck, real tight, I tied a rope around my neck that I tore from my smock. I did that on three or four occasions, then swallowed a battery and swallowed a razor. The battery is still in me right now.”

A brutalist white building that houses around 1,300 men and women, the Hampton Roads Regional Jail has been called “by default, Virginia’s largest mental hospital” because it’s a dumping ground for the sickest inmates from surrounding jurisdictions. In December, the Justice Department issued a scathing report that said the jail violated the constitutional rights of mentally ill prisoners by housing them in solitary for lengthy periods with woefully inadequate treatment. At least 19 inmates have died by various causes since 2015.

“It’s unconscionable to put someone with serious mental illness into a segregation cell for 23 hours a day and let their demons chase them around.”

According to the Justice Department, about a quarter of the 774 cells at Hampton Roads are 80-square foot units “designated as restrictive housing.” Prisoners are housed alone, “typically for 22 or more hours per day during the week and even longer on weekends.” The report said inmates started calling mental health treatment “crack therapy,” because staff would only speak to them “through a crack at the hinge of the solid metal door.”

Jail officials have requested additional staff and funding to address the problems, but the situation at Hampton Roads is reflective of the much larger problem nationwide with solitary and the way mentally ill people are incarcerated. Some states have tackled the issue more progressively than others. In the fall of 2017, Colorado became the first — and so far only — state to comply with the UN’s Nelson Mandela rules by limiting time in “restrictive housing” to a maximum of 15 consecutive days and only for “the most serious violations” of prison rules.

The Colorado reforms were prompted by a tragic crime. On the evening of March 19, 2013, Tom Clements, the director of the state’s Department of Corrections, was shot to death at his home by a former inmate who’d been released directly to the street after spending nearly six years on 23-hour-a-day lockdown. The killer, 28-year-old Evan Ebel, had previously murdered a Dominos delivery driver and stolen his uniform. He posed as if delivering a pizza, then opened fire with a 9mm pistol when Clements opened his front door. Ebel fled the state and was killed two days later in a shootout with police in Texas.

Rick Raemisch, the man hired in 2013 to replace Clements and overhaul Colorado’s prison system, said he was stunned to learn that the state was still sending around 300 inmates per year from solitary to the streets, despite previous efforts by Clements to curb the practice. Raemisch banned the direct releases entirely in 2014.

“My personal feeling about it is that solitary confinement is so harmful you’re literally making a person worse than making them better,” said Raemisch. “Who wants to live next to that person when they get out? You’re letting a lit stick of dynamite out the door.”

Raemisch retired last year, but he believes his approach in Colorado can work elsewhere. State prisoners now have access to “de-escalation rooms” that are painted in soft colors and have soothing noises piped in. Combined with other changes, Raemisch said, “the results are remarkable.” The state’s “supermax” prison is now vacant. Colorado banned solitary at its two mental health prisons and saw assaults, self-harm, and suicides decrease dramatically. Raemisch adopted the philosophy, “You can restrain, but you don’t have to isolate,” and got even the most dangerous inmates out of their cells for a minimum of four hours per day, at “restraint tables” with up to four other prisoners for classes and activities.

“It’s unconscionable to put someone with serious mental illness into a segregation cell for 23 hours a day and let their demons chase them around,” Raemisch said. “When I see that happening, typically it’s because that state has not been given the resources to effectively treat those folks, and typically they’re so disruptive they don’t know what to do with them.”

According to Aro and the guards, ADX is already working to get certain prisoners out of their cells more often, up to 20 hours a week in some cases. Those who do well can be rewarded with funds on their commissary accounts, a big incentive since ADX prisoners are not allowed to earn money by working at a prison job. The warden recently allowed two inmates — one a 72-year-old in his 18th year at ADX — to paint murals inside the prison.

My request to visit and see some of the improvements firsthand was denied, and it appears that no interviews have been granted with prisoners since 2001. (Several letters I sent to current ADX inmates went unanswered, and the BOP would not confirm they were delivered.)

“We don’t want the public to know what we do, and we justify it under the guise of security,” said Hood, the retired ADX warden.

Hood noted that Marion and Alcatraz, the two previous supermax prisons, each had lifespans of about 30 years, and ADX is currently nearing that milestone. The BOP already has plans for a new supermax facility in Thomson, Illinois, though there are currently no public discussions about closing ADX. Either way, the use of extreme isolation will continue. Even Hood, who presided over hundreds of post-9/11 force-feedings that still continue today at ADX, thinks there has to be a better way.

“Things change, the world changes,” Hood said. “I think you’ve done as much as you could do in that facility. It’s a different mindset now.”

Currence pleaded guilty on Aug. 22 to charges of strangulation and assault for his attack on Mary, and was also convicted of two counts of indecent exposure for attempting to masturbate in front of nurses at the hospital. The verdict on a fifth charge, “abduction with intent to defile,” remains pending until October 25. If convicted, he faces 20 years to life in prison, though likely in a Virginia state facility, not ADX

“I don’t want him to ever have the ability to hurt anybody again,” Mary said, “so I’d be happy with that.”

Currence says the prospect of another long stretch in prison is too much to handle. He already predicted his future once during his deposition at ADX, and during our interview at Hampton Roads he once again saw darkness on the horizon.

“I’m teetering on the edge,” he said. “I’m still trying to get back to the hospital and get the help that I need because, I’m not saying I’m going to do it now, but eventually I might kill myself.”

Videos by Kathleen Caulderwood and Jessica Opon. Graphics by Hunter French.

Cover: Jabbar Currence in Hampton Roads Regional Jail. Photo by Kathleen Caulderwood.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.