Internal Documents Show Why the NYPD Tries to Be ‘Funny’ Online

Credit to Author: Caroline Haskins| Date: Mon, 22 Jul 2019 18:44:14 +0000

On July 17, 2014, the New York Police Department put Staten Island resident Eric Garner into a chokehold while apprehending him for allegedly selling cigarettes illegally. Garner told police “I can’t breathe” 11 times before losing consciousness. Officers did not perform CPR on Garner, and neither did EMT when they arrived at the scene. Garner was pronounced dead in the hospital about an hour after the incident.

This week, exactly five years after Garner’s death, Mayor Bill de Blasio doubled down on his decision to not fire Officer Daniel Pantaleo, who placed Garner in a chokehold. Pantaleo will also not be held criminally liable. The decision ignores repeated demands for justice from local residents and activists who have organized both in-person and en masse on social media.

That same day, the NYPD Twitter account tweeted about World Emoji Day.

Motherboard has obtained and is publishing an internal guide that may help explain the strategy behind that tweet, and the NYPD’s social media presence across platforms. Police are explicitly told to “be funny” by cracking jokes and using emojis, and to take “victory laps” by sharing evidence of arrests and confiscations. The documents note that the goal of NYPD social media accounts is to “build, and maintain trust between the Department and the communities it serves.”

The U.S. military, and police departments around the country, are known to follow a similar social media strategy. Law enforcement often uses social media to speak in a way that’s cheery and cutesy, belittling and heartless, or some combination of these things. The NYPD is no exception. In 2014, the NYPD tweeted a quote from A Few Good Men which, in the movie, was used to justify a murder. (They later deleted the tweet.) Earlier this year, it triumphantly tweeted about a “clean up” of a homeless encampment in the East Village.

Motherboard obtained seven slide presentations, which include examples of “funny” police tweets, Twitter dos and don’ts, and at one point, a slide is completely dedicated to displaying an image of YouTuber PewDiePie. Motherboard also obtained two “Operations Order” documents that spell out the department’s official social media goals and policies.

Non-commissioned officers (NCOs) put in charge of the NYPD’s social media accounts are explicitly instructed to be both friendly and feared. However, the NYPD has a poor record on civil liberties. A New York Department of Investigation (DOI) report shows that the NYPD has received almost 2,500 complaints of biased policing since 2014. The NYPD closed 1,918 of those complaints. Zero investigations have been issued. A Buzzfeed investigation released last year shows that between 2011 and 2015, hundreds of officers have committed severe acts of misconduct and violence and have been allowed to keep their jobs. This record complicates the way the NYPD presents itself on social media.

NYPD social media policies makes the department’s 119 Twitter feeds into a jarring mix of images: police posing with children, confiscated guns, missing or wanted people, and police dogs. Police want to tell people that they’re charming and approachable, but also powerful and sometimes frightening.

A document titled “Operations_Order_28,” dated June 2017, tells police that the goal of NYPD social media is to “build, and maintain trust” with city residents. Several documents instruct social media NCOs to post pictures of NYPD officers.

A slide presentation titled “Best_practices_prezi” instructs police to be “authentic and funny.” The slide notes that “(expectations are low…)” for humor.

“Funny tweets are more likely to be shared,” the slide presentation says. “Don’t say anything you wouldn’t say in any other public forum.”

“Funny” tweets are recommended because maximizing shares and engagement is recommended per NYPD policy. Operations Order 28 instructs officers to prioritize engagement.

“Develop innovative and informative social media messaging with the goal of cultivating public engagement,” the document reads.

Examples of funny tweets, according to “Best_practices_prezi,” include using a lot of emojis, making jokes about recent raids and arrests, and making joke-infused warnings about possible crimes.

The presentation has a section in which officers are prompted to select a good tweet an a bad tweet. An example of a good tweet, according to the presentation is, “Officers just arrested a naked man in the bison paddock in GG Park. The bison seemed unimpressed.” Meanwhile, an example of a bad tweet is, “Between 11/30/13, 9pm and 12/01/13, 9:45 am on the 1900 block of Clement St, a suspect hopped the fence to the… [link]”

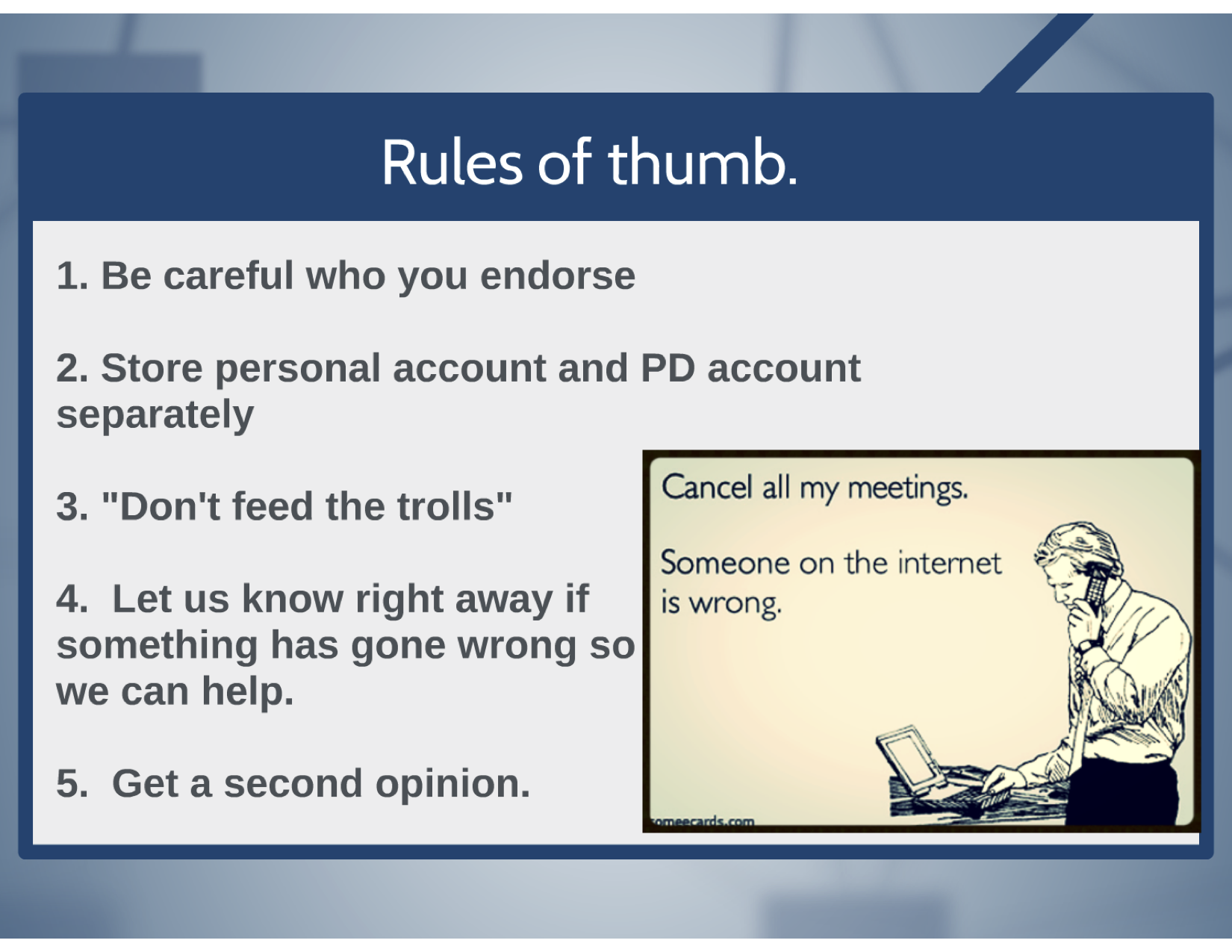

Police are also instructed to avoid making blunders on social media. A slide presentation titled “Twitter_mistakes_prezi” tells police, “Don’t make light of harsh situations,” and to sometimes seek second opinions. It also lists five rules of thumb for police.

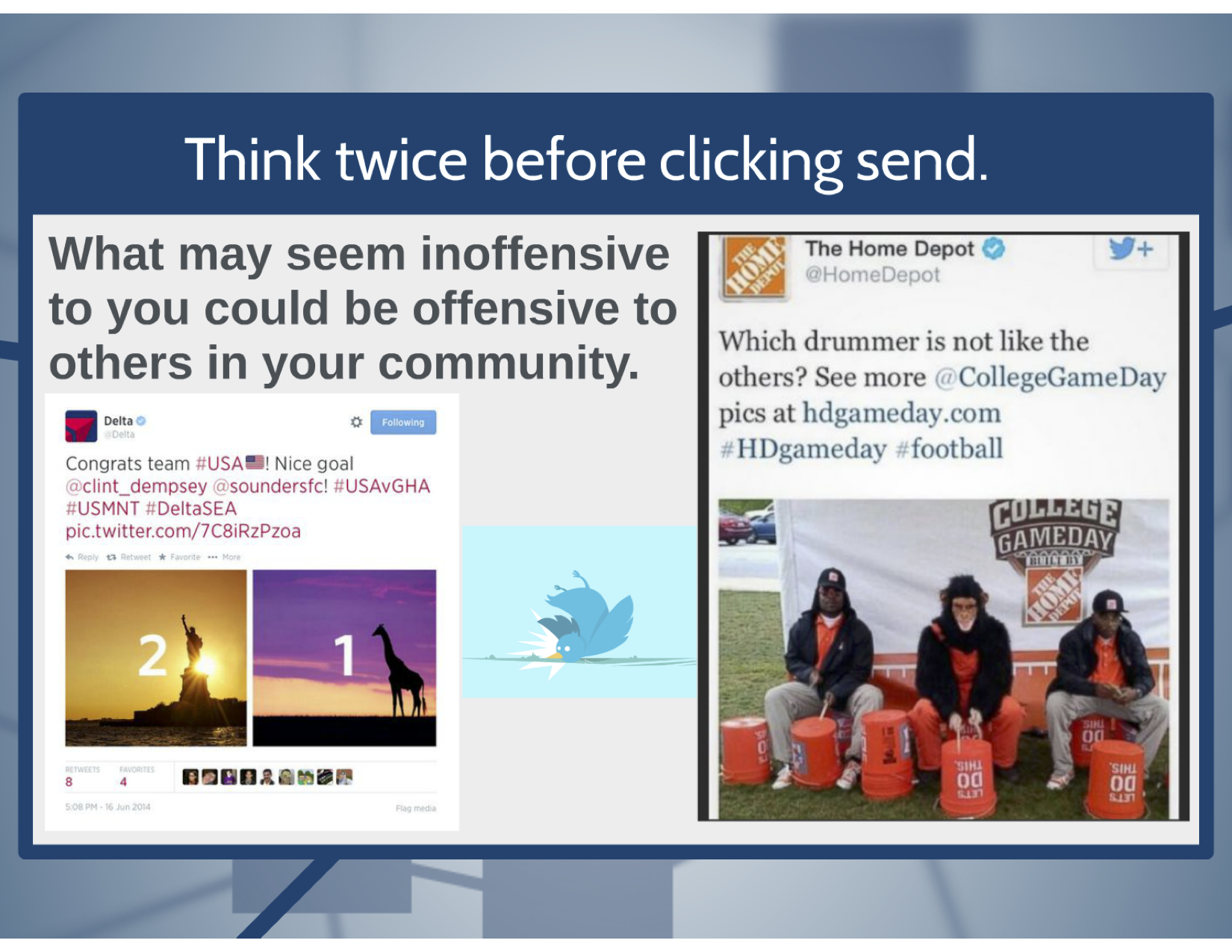

“What may seem inoffensive to you could be offensive to others in your community,” the slide presentation later warns. The examples of content that could be offensive to “others” in your community are outrightly racist.

A slide presentation titled “Promotional_training_prezi” warns officers, “You are always in the public eye,” and displays the logos of WorldStar Hip Hop and Copwatch, platforms that are known to sometimes share images and videos of police violence and misconduct.

Other documents show that there is no basis of social media literacy required for NCOs that are interested in operating social media accounts.

“It’s not about computers,” the slide presentation says. “Previous knowledge is not required. Yes, it’s risky. But the good outweighs the bad.”

“Promotional_training_prezi” also notes that all “commanding officers and staff are trained” before getting access to social media accounts. Once trained, social media access is heavily delegated.

“How do we approve everything? WE DON’T!” one slide says.

“Promotional_training_prezi” also shows a side-by-side comparison of the social media landscape in 2012 and 2017. An entire slide in the presentation is dedicated to displaying an image of PewDiePie. In 2017, seemingly the same year the presentation was given, PewDiePie used a racial slur on his channel and directed users to an antisemitic channel (which he claims was accidental).

The slide presentation also tells police, “AND DON’T FORGET YOUR VICTORY LAP!” This means that police are told to share results of certain investigations. In practice, this often means sharing images of confiscated guns or counterfeit items.

It’s reasonable for any public-facing entity to humanize their workforce. But the NYPD’s attempts to improve its public image with social media don’t address the public’s biggest concern: years of allegations of misconduct.

When reached by Motherboard for comment, an NYPD spokesperson said in an email that the goal of its social media presence is to let police “communicate directly with their residents, hear their concerns, and update them about Neighborhood Policing and public safety issues in real time.”

“Since 2014, the accounts have amassed over 1 million followers, have helped launch hundreds of community events, forged relationships, introduced residents to their own local officers, allowed us to gauge issues of concern from the public, as well as notify them in real time regarding emergencies,” an NYPD spokesperson said. “Use of social media accounts has also helped solve and prevent crimes through tips, awareness and community interaction.”

When asked about the DOI report, the NYPD referred Motherboard to a press release and added the following.

“I want to reaffirm that there is zero tolerance for bias in the NYPD,” an NYPD spokesperson said. “Bias is often tough to prove because you need to show intent. The OIG itself couldn’t conclusively prove bias in 888 cases that it reviewed. But that doesn’t mean the NYPD isn’t taking action.”

One slide presentation argues that social media use can help supplement traditional policing. A slide displays NYPD officers testifying about the impact of social media.

“People I never met before were able to share community concerns and comments,” NYPD Inspector Fausto Pichardo said, according to the presentation. “People would come up to me on the street and say ‘Hey! I follow you on Twitter!’ Before, I would have probably walked by them and they wouldn’t know I was the CO.”

“With social media I can engage my community at any time of the day from anywhere,” Detective Inspector Chris Morello said, according to the presentation. “I get messages from people in real time about what’s happening — they can now be my eyes and ears.”

But of course, NYPD officers also use more covert methods to supplement their policing. The NYPD has used Palantir, a powerful, secretive data aggregation tool that enables law enforcement to learn nearly everything about a person from a simple search query. The NYPD has also tested controversial predictive policing technology, which claims to be able to “forecast” crime by sending police to places where crime has already occurred. It has abused facial recognition technology by submitting celebrity look-alikes of subjects on camera in order to search for positive matches. It has fleets of drones, which have been deployed at events like the NYC Pride Parade, despite the fact that LGBTQ activists have resisted heavy police presence at Pride events.

According to the NYPD, social media is a way to “connect and engage with local businesses, residents, and other members of the community.” However, social media has never been a tool for the NYPD to be transparent about the activity that actively concerns and frightens New York residents. Trust can’t be extracted through tweets.

All of the documents that were used to inform this article are now public and viewable on Document Cloud.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.