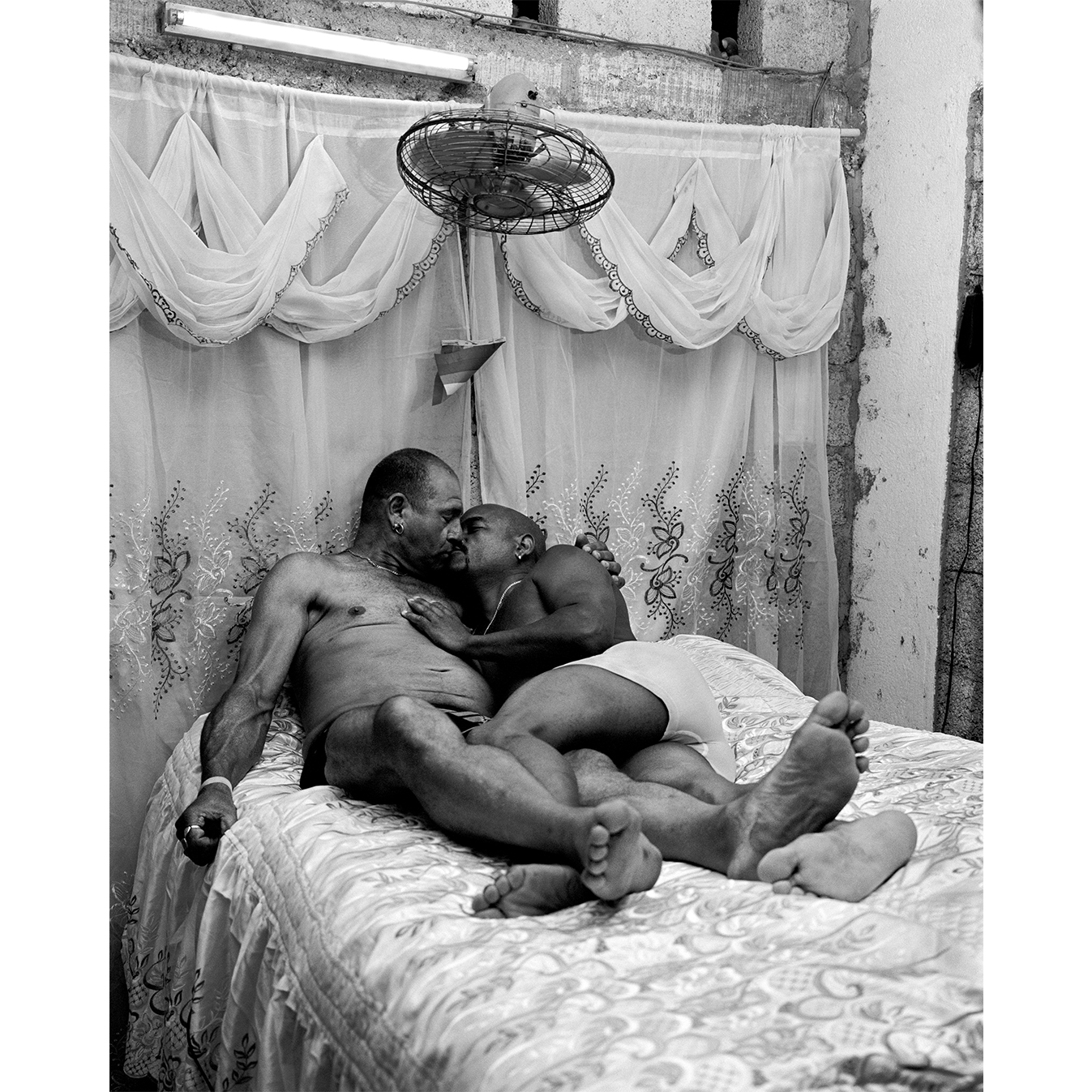

These Portraits Capture the Stunning Diversity of Queer Cubans

Credit to Author: Alexis Ruiseco| Date: Fri, 28 Jun 2019 13:03:06 +0000

Born in Cuba and currently living in Brooklyn, artist Alexis Ruiseco-Lombera has dedicated their work to documenting and uplifting Cuba’s LGBTQ community, and not just during Pride. Ruiseco-Lombera’s medium alternates between performance, photography, and writing to illustrate their experiences as a non-binary Cuban artist alongside those of other LGBTQ Cubans.

Ahead of the 50th anniversary of Stonewall, Ruiseco-Lombera has had the legacies of Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Riveria in mind, legacies that for too long were erased, they say. As an artist, Ruiseco-Lombera works to prevent a similar erasure of the Cuban LGBTQ community by creating archives of queer Cuban history and culture, as this series, Añoranza: Portraits of Trans and Queer Cuba.

These photos—created in collaboration with Rafael Suri-Gonzalez, a scholar, activist, and friend of Ruiseco-Lombera’s who recently passed away—were taken in the Villa Clara and Mayabeque providences of Cuba. We spoke to Ruiseco-Lombera about this series and why they feel called to archive the history of their community at this moment in time.

VICE: What motivated you and Rafael to begin this series?

ALEXIS RUISECO-LOMBERA: I would first like to take a moment to hold in honor the efforts of late activist, organizer, researcher, colleague, and dear friend Rafael Suri-Gonzalez, who passed away earlier this year. He and I had been in collaboration over the last three years, making photographs within trans and queer communities.

Our motivation came from a deep desire to document and archive the image of our community as the trans and queer politic flourishes on the island, with a particular focus outside of the capital. Considering the contingency of the trans and queer community and its transformation over the last 12 years, and the political timing of Cuba’s most recent rapid changes, history is moving at a rapid rate, and documenting that transformation is imperative.

What role did Cuba’s historical treatment of the LGBTQIA+ community play in your decision to create this series?

The history of official and popular homophobia and transphobia under the Revolution makes public naming of gender and sexual identity difficult, and often dangerous until this day. 14ymedio recently reported la Seguridad del Estado [national security] stopped close to 300 activists, citizens, and allies marching independently of the state, during the XII Jornadas Contra la Homofobia y Transfobia in La Habana [the 12th annual Conga Against Homophobia in Havana]. At least seven activists were violently arrested. Amongst the detained were Iliana Hernández, Oscar Casanella, Ariel Ruiz Urquiola and Boris González Arenas, all liberated within 24 hours.

Confrontations like this reflect the lack of public narrative to frame the knowledge of institutionalized trans and homophobia. I am responding to that history and present day trans and queer erasure, violence, and marginalization.

What does it mean for a trans and queer Cuban living in Cuba today to declare “I am here”? Why is it necessary?

Cuba is elusively restructuring boundaries to erase us, to keep us silent, policing trans and queer bodies to follow certain conduct, outside of which you will be persecuted. Being open is an unspoken invitation for pain, struggle, and adversity. Trans and queer Cubans have to take up necessary space and not disappear into silence. During the unprecedented gathering to celebrate the XII Jornadas, the loudest voice was the collective sound of the 300 activists, citizens, and allies that marched. Chanting “CUBA DIVERSA! CUBA DIVERSA!” was their way of saying “I am here.”

Can you talk about your process? How did you find your subjects; did you have connections with them before?

Introductions were facilitated by Rafael when I was in Placetas and my aunt Aida, who is openly lesbian, in my birth-town Güines. Spending time in both places with my family and meeting queer and trans people, sometimes I’ll grab a coffee with them, stay for dinner, or visit, focusing on long-term connections, trust, and intimacy before we take our picture. I ask each person how they would like to be photographed, giving them agency to present themselves in whatever ways they choose, and ask them to negotiate switching between photographer and subject, letting each person construct their own self-portrait alongside the portraits I make of them. The most nuanced images of each person end up being the ones they make of themselves. The series will most likely become a series of self-portraits.

How does the fact that you live in Brooklyn, rather than in Cuba, affect your approach to this series?

I have to be careful not to conflate the trans and queer politic that has flourished here [in New York] with the one developing on the island. I approach the archive with genuine receptivity and I’m attentive to the local, oral, and erased histories and landscapes, compared to the state’s archive of the community—thinking less about authorship and ownership, and more about stewardship and being a guardian of this work. As a Cuban that parted from their homeland, my lens is doubled—existing neither here nor there. I always remind myself that something different could have happened when I left in 1995, and I could be living in the countryside of Cuba.

You hope that this series serves, in part, to archive queer history and increase queer visibility in Cuba. Have you found others working to elevate the community in a similar way?

Navigating through Miami, New York, and Cuba, I’ve only met a few Cuban trans and queer cultural producers, and most of them do not approach the developing narrative in Cuba. My hope is for my transcultural production to continue intersecting with the efforts of the activists and organizers that are risking their safety to do this labor.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.