Meet Sam Kerr, Australia’s first women’s soccer superstar

On the eve of her third World Cup, Sam Kerr has her eyes firmly set on glory, taking down the US and what success would mean for women’s sport back home. (3:53)

AN HOUR BEFORE before Perth Glory take the field for their final home game of the season in Australia’s W-League, the line to enter the Dorrien Gardens soccer complex stretches to the end of the block. Outside the entrance, volunteers in purple shirts sell tickets to the game at a plastic folding table: $15 for adults, $5 for kids. As fans flow into the venue, they greet their neighbors and post up around the chain-link fence that borders the field.

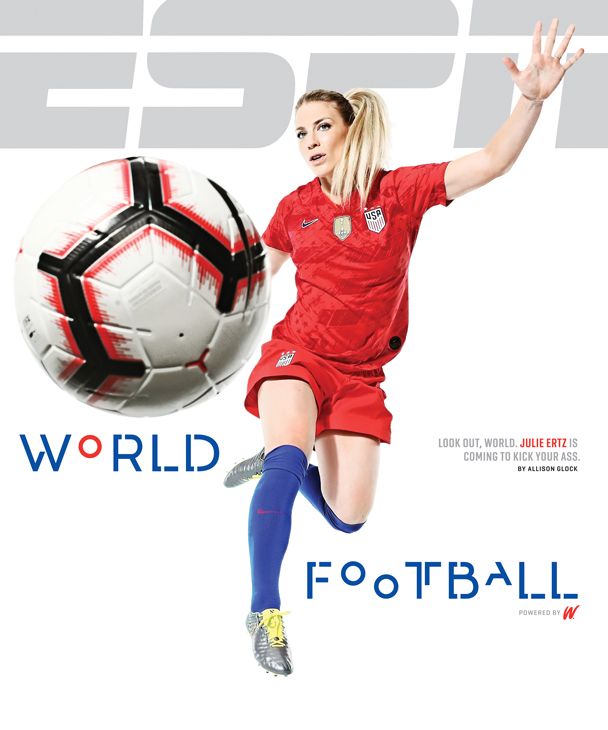

For more on the U.S. and global stars of the upcoming 2019 Women’s World Cup, check out the June issue of ESPN The Magazine.

• Meet the 23 members of the USWNT 2019 World Cup roster

• How Bob Marley’s daughter saved Jamaican women’s soccer

• Get ready, world: Here comes the marvelous Mal Pugh

• Julie Ertz is the ass kicker of the U.S. women’s national team

• More Women’s World Cup coverage

The 1,212 fans — the most to attend a Glory home game since the league launched in 2008 — are here, crammed into this tiny stadium, for their last chance to see their star: Glory captain Samantha Kerr, the most prolific goal scorer on two continents and Perth’s hometown hero. “I don’t think she’ll be back next year,” says Harry Ray, a longtime fan who arrived early with his wife and young son to snag seats in the stands. “I’m just enjoying her being here now. I can’t believe I get to watch someone this good in person. Sam is a level above.”

Kerr, who also plays for the Chicago Red Stars in the NWSL, is Australia’s first women’s soccer superstar. She outearns the rest of the Glory roster combined and, including endorsements, is the highest-paid women’s soccer player in the country. When she signed a Nike deal in March, the media dubbed her “the millionaire Matilda,” a nod to the official nickname of Australia’s women’s national team. Unlike the majority of her W-League peers, who make on average about $14,000 per 12-game season, Kerr is a blue-check celebrity, her joyful backflip celebrations featured in international TV commercials and her image plastered on billboards throughout Australia. “Sam transcends the sport from the highest level to the grassroots community,” says Greg O’Rourke, Football Federation Australia head of leagues. “She has a magical blend of humility and showmanship. People just love her.”

Kerr’s stardom is the latest breakthrough for a league that started just over a decade ago. For most W-League players, soccer is still a passion, not a profession. Last season was the first in which all 57 W-League games were broadcast live on television, and only last year did the W-League begin selling jerseys. (Ray, for the record, is wearing a men’s Glory jersey his wife special-ordered for him with Kerr’s name and number on the back.)

“Most of my teammates work 9 to 5, so the commitment level is different [in the W-League],” says Kerr, 25, a few days later, between bites of zucchini and haloumi fritters at one of her favorite lunch spots. Her dark hair is pulled low into a ponytail, still wet from a dip in the Indian Ocean with her 5-year-old boxer, Billie. “Sometimes it’s frustrating,” she says. “You’re giving up your life for the sport, and for a lot of players, it’s just another part of theirs.”

So why is one of soccer’s brightest stars playing in Perth with part-time teammates in a venue the size of a high school football stadium? Because she can’t imagine preparing for the most important tournament of her career anywhere else. “To play in front of Perth fans is special,” Kerr says. “They know me on a different level, as the hometown kid who plays for fun. They see me as who I am.”

“THIS FAMILY GETS together for three occasions,” Kerr’s father, Roger, says, extending his arms as if to embrace everyone in the room. “Weddings, funerals and Sammy’s home games.” It’s half-time at Dorrien Gardens, and four generations of Kerr’s family are crowded inside the concessions area at the top of the stadium, about 40 deep at last count, all sharing stories and photos from Kerr’s career. “She’s great, right?” asks Kerr’s 87-year-old grandpa, Harry Regan. He doesn’t wait for an answer. “You’re not going to find much better.”

As Kerr’s family tells it, she was a precociously gifted athlete in a family of gifted athletes, a child who ran before she walked and could throw accurately before the age of 3. Her trademark round-off backflip goal celebration? She taught it to herself on a grassy hill near her school when she was 9. She’d seen gymnasts do flips on TV and thought they looked fun. “I worked out that if I went down a hill, it would give me more chance to get ’round,” she remembers.

Back then, Kerr played cricket and netball and sprinted on the school track team. But her heart belonged to Aussie rules football, a rugby-like sport played on a modified cricket field. “I loved the competitiveness, how fast-paced and rough it was,” Kerr says. “I loved getting down and being gritty.” The youngest of four, Kerr learned the game from her dad and her oldest brother, Daniel, who played professionally and won a championship with the West Coast Eagles. “When I was asked what I wanted to be when I grew up, I would say, ‘a West Coast Eagles player!'” Kerr says. “I wanted to do exactly what my brother did.”

She didn’t know that there was no path at the time for a girl to become an AFL star, even a girl who could outsprint most boys in the league. (The AFLW wouldn’t launch until 2017.) But as the boys grew bigger and Kerr began returning home with black eyes and bloody lips, her dad and brother called a timeout. “When she was about 12, she took a bad hit in a game and we decided to push her into soccer,” Daniel says. “Sammy picked things up so quick.”

— Who will rule the Women’s World Cup?

— Why you won’t see the world’s best player at the Women’s World Cup

— Women’s World Cup team preview: Australia

— Women’s World Cup 2019: Team previews, schedule, how to watch, news and analysis

That decision wasn’t popular with little sis. She didn’t understand the rules, hated the lack of contact and felt untethered as she tried every position in search of a fit. “I didn’t know offsides or how to take a throw-in,” she says. “I went from being one of the best players on my Aussie rules team to not being good at all. It was like going to a new school midway through the year. And the fact that I’d been taken away from something I loved made it even worse.”

But Kerr’s background in Aussie rules helps define her playing style today. “She attacks every ball,” says USWNT midfielder Julie Ertz, Kerr’s teammate in Chicago. “She’s so good inside the 18 that you always have to know where she is. She’s so dangerous.” After a couple of seasons in junior soccer, Kerr found her footing as a forward and drew the attention of the national team. But even when she was recruited by the Glory at 15 — one year after the W-League launched in 2008 — and made her debut for the Matildas the same year, she still couldn’t imagine a future in women’s soccer, a sport few fans or sponsors took seriously in Australia.

“So I didn’t take it seriously,” Kerr says. “When I was young, it was always like, ‘She’s 16 and she’s scoring. She’s 18 and she’s starting. That’s good.’ I was just happy to be medium. Then something changed.”

In 2014, a year after she’d started playing in the NWSL, she was sidelined by a string of injuries for nearly two years. She felt lost, questioned whether she would return the same player and swore never to take the game for granted. “I thought, ‘I want to be more than average,'” Kerr says. “I changed the way I thought about myself.”

In 2017, Kerr scored the most goals in the NWSL, the W-League and Australia’s first Tournament of Nations, and became the NWSL’s career scoring leader. Her scoring tallies did not go unnoticed, and in early 2018, she was faced with the biggest decision of her career.

Barcelona and Chelsea made her offers. Playing for a European superclub would bring recognition and prestige, vaulting her into contention for awards such as the Ballon d’Or and FIFA Player of the Year, for which she had been previously overlooked. Kerr’s supporters had blamed her omission on a lack of respect for Australian players and the NWSL, and here was her chance to seize the spotlight. “Europe is the epicenter for football and awards,” says former USWNT midfielder Heather O’Reilly, who plays for the North Carolina Courage. “The visibility of women’s football overall isn’t where it should be, so you have people making decisions on players they’ve never watched. It would be a lot sexier for Sam to play for Lyon or Manchester City. At Sky Blue FC [in New Jersey], she scored ridiculous goals, but no one knows Sky Blue.”

And then there was the money. With the Red Stars, Kerr was making the league maximum of $44,000, plus less than half of that with the Glory. “I worked out that one of my two-year deals in Europe would be worth the same as 12 seasons in the NWSL,” Kerr says. “I wondered if I would regret not taking that amount of money.”

Then the FFA did something unexpected. In an attempt to keep Kerr at home, it offered to make her the first “marquee” player in the history of the W-League, emulating a status granted to one or two players on each men’s team in the A-League. As a marquee, Kerr would be paid nearly AUS$400,000 by the FFA (around $286,000), including a bonus for being the face of its World Cup 2023 bid. Suddenly, Kerr’s decision was no longer just about money. “And that made it so much harder,” she says.

For over a month, Kerr discussed with friends and family and made pro-and-con lists. “It was a really stressful time,” she says. “But I finally thought about what was important to me.” Having watched Daniel navigate the pitfalls of being one of Australia’s biggest AFL players, she realized she cared only about success, not fame and fortune. “Playing in a nice stadium for a famous club and having more money wasn’t going to make me a better player,” Kerr says. “It took me a while to realize the best decision for me and my football was coming home.”

Matildas captain and star striker Sam Kerr sits down with ESPN to share her journey from aussie rules to soccer, and what coming home to Perth truly means.

When the FFA announced Kerr as its first W-League marquee, the story made international headlines. “It showed Sam’s character and what Australia means to her,” says former Matildas star Heather Garriock, coach of Canberra United in the W-League. “It’s fabulous for the league to have a player like Sam on our TV screens week in and week out. Her marquee status really fast-tracked how football is perceived and received in Australia.”

During the Glory season, Kerr and her longtime girlfriend, Nikki Stanton, a midfielder for the Glory and Red Stars, live with Kerr’s parents in South Fremantle. They eat Mom’s home-cooked meals, take Billie for walks on the beach and watch cricket on TV with Dad.

But returning to Perth was about more than home cooking. Kerr realized she has the power to change how Australians think of themselves on the global stage. “When I was growing up, I never thought about being the best in the world,” she says. “But when you rub shoulders with national team players from other countries, you realize they have that mentality. I want to change the mindset of young girls and boys growing up in Australia, to show them they can be the best in the world.”

KERR IS STANDING shoeless and sweaty in the bowels of AAMI Park in Melbourne, her feet in constant motion as she addresses the media in early February. While some people talk with their hands, she expresses herself best while dribbling a ball, real or imaginary, between her feet.

Kerr is the only player the media asked to interview tonight, not only because she scored a hat trick and notched an assist in the game but also because of the controversy that has suddenly engulfed the Matildas.

Three weeks ago, and less than five months before the Matildas’ first World Cup game, the FFA abruptly announced it had sacked coach Alen Stajcic, who since 2014 had transformed the Matildas into Australia’s best-ever national team. Citing two confidential surveys given to the team and its support staff, the FFA told the media that Stajcic had created an “unsatisfactory” work environment that had reportedly “deteriorated in recent months” but provided no further explanation.

Several Matildas posted messages of support for Stajcic on social media, but Kerr remained silent. That afternoon, journalists showed up at a clinic hosted by the Glory hoping to hear from her. But knowing that whatever she said would make headlines the next day, Kerr opted not to meet with the media. They then publicly accused her, as the league’s marquee, of being silenced by the FFA. The next day, Kerr took a breath and posted to Twitter.

“I have not been gagged by the FFA,” she wrote. “I have not commented because I wasn’t ready to comment while I am still shocked and upset. My trust was in Staj to lead us to the World Cup final & I believe he was the best coach for that. Thankful for everything he’s done for me and the team.”

A few moments later, Kerr posted one final thought on the topic: “When something drastic happens in life, Twitter is not the first place I go.”

Stajcic’s unceremonious firing sent the team and media coverage into chaos. Fans blamed the players, players blamed the FFA, and Stajcic remained silent. Reports surfaced that only a small percentage of players had taken the surveys, and rumors circulated about the FFA’s ulterior motives. Two assistant coaches quit in protest. To this day, Stajcic, who now coaches in the A-League, maintains his innocence, and on May 31, FFA Deputy Chair Heather Reid issued a public apology for the part she played in implying misconduct from Stajcic in private communications to members of the media.

The situation threatened to derail the Matildas, and Kerr realized she needed to step up. “I thought about how [Stajcic’s firing] changed my role on the team,” she says, a few weeks after the news broke. “I’m going to have to think about what I say and keep a lot of things inside. It’s about preaching positivity. People who have influence on the team are going to be really important.”

In Melbourne, the media finally have their chance to ask her if “the Stajcic situation” has become a distraction. “Whatever is gonna be is gonna be,” Kerr says, shrugging her shoulders and punctuating the thought with a disarming smile. “We’ve got a World Cup in four months. We can’t waste a day thinking about the past.”

SIX WEEKS AFTER the FFA introduced former men’s national team assistant coach Ante Milicic as head coach of the Matildas in March, Kerr is sitting on a couch in the lobby of a Denver hotel, upbeat about the team’s prospects even after a 5-3 friendly loss to the U.S. two days before. “We’ll be better come June,” she says.

In conversation, Kerr is soft-spoken and direct, loves making what she calls “bad dad jokes” and laughs without checking if anyone is laughing with her. “Did you hear the call when I scored on Thursday?” she asks, then imitates the Midwestern announcer, unaware she’s drawing the attention of a full lobby. “Goaaaal! Saeemkurrrrr! Saeemkurrrrr!” she shouts while laughing.

Despite the lingering confusion over Stajcic’s dismissal, Kerr says Milicic has raised the standard for everyone in the program, from the players to the bus drivers. “He’s brought a level of professionalism the women don’t usually see,” she says. “I think that comes from coaching the Socceroos and knowing how the men have been treated. He’s been going to the federation and fighting for us.”

Thanks to Milicic, the team no longer gets anchovies in its catering — “Before Ante, we would have never thought to complain,” Kerr says. The Matildas travel with a full-time massage therapist and will prepare for the World Cup at the same world-class training camp in Turkey the men used last year. “Hell no, we weren’t already going there,” Kerr says. “Ante set that up for us. It feels so good. He’s created an atmosphere where everyone wants to be better and give more.”

Milicic’s higher standards have helped Kerr understand her own value, as well as the importance of speaking up. “I’m the first, so I struggle with knowing my worth,” she says. “I’m sure in the U.S., players like Alex [Morgan] have [Megan] Rapinoe and [Christen] Press to talk about this stuff with.”

KERR IS WALKING barefoot on a beach near her home, Nikki and Billie at her side, the Indian Ocean lapping at their feet. Off the pitch, she moves with the slow swagger of a running back saving energy for Sunday. But when Billie takes off for the water, Kerr breaks into a sprint, dives under the waves and emerges laughing, the 35-pound pup lifted high above her head.

Kerr knows that if she plays well in France, she might have to give all of this up. Europe, with its riches and accolades, will call again, and her decision will set the standard for Aussie women who follow.

But she’ll be better equipped next time. “I have access to stats now that show I sold the most jerseys for Perth and put me as the No. 1 player in TV ratings,” she says. “Last time, I didn’t know.”

“Fans don’t see her as a female athlete playing a female sport,” O’Rourke says. “They see her as one of the top three athletes playing soccer in Australia.”

So when the time comes, Kerr won’t settle for less than she deserves. She just has to decide what that is.