Mr. Skin Fossilized. Howard Stern Modernized

Credit to Author: Alex Norcia| Date: Wed, 22 May 2019 20:57:38 +0000

I grew up in New Jersey, in the wooded central part of the state outsiders seem to not know exists. It’s a diverse and paradoxical land, filled with lawyers and doctors, plumbers and electricians. Much of my family hauls scrap. Bernie Madoff’s right-hand man owned a mansion there and, after the surrender of his house, moved into an apartment complex across the street from my mother’s condominium, on house arrest. Whenever he stepped onto the sidewalk to smoke a cigar, my brother and I would make faces at him, certain he couldn’t walk much farther down the road. That action felt emblematic of the region—cartoonish, obnoxious, self-regarding. It was also extremely fun.

Jersey breeds its own species of human beings, angry and flamboyant creatures defined by a place of betweenness, by a place constantly rubbing against something else. Nothing convinced me of this more than when I was a teenager, driving from my mom’s house to high school, my car radio switching between the stations in Philadelphia and New York. I could almost always get the ones airing out of Manhattan, but Philly 93.3 WMMR (Pierre Robert’s “Great day in the morning!”) required knowing certain locations: the parking lot of the YMCA; Country Club Road (usually); outside the Bridgewater Commons Mall (sometimes). At this point, K-Rock 92.3 was beginning its slow descent. It had chugged along from 1985 to 2005, almost exclusively on the popularity of The Howard Stern Show, which had aired for that same period. But two decades was enough for Howard, and, endlessly exhausted from the FCC and its fines, he decided to pack up his microphone and head to Sirius, where he was free to curse and talk about masturbation.

It was a profound loss. Although I was too young to be a diehard fan, Stern had already seeped into my head. My uncle’s childhood bedroom, maintained by my grandparents as if it was perpetually 1987, had a waterbed and headshots of the unmistakable personality—curly hair, sunglasses, a golden hoop earring. There were things I knew that I could not tell you how I learned—like how, in 1994, Stern ran against Mario Cuomo for the governorship of New York on the Libertarian Party ticket, promising to restore the death penalty if elected. It was as if Stern was a contagion in the air, a virus. My father had been to his rallies in Midtown Manhattan. I would have gone, too, I suspect, had I been born in a different era.

“I don’t look at my audience as a demographic,” Stern said in an interview with Fox News anchor Bill O’Reilly, after he announced his transition to satellite in 2005. “I look at it as a psychographic.” When prompted by O’Reilly to answer whether he attracted more men than women as listeners, Stern responded, “I have always envisioned the guy—the guy—I’m doing the show for is driving to work, he’s a buddy of mine, we’re in the locker room, and, man, we’re talking reality. We’re not talking politely. We’re being honest. We’re being real.”

These guys fill up much of New Jersey, and the East Coast. They’re the types who are slightly overweight and get very drunk at professional baseball games. And they loved K-Rock. That station was synonymous with Stern and rock ‘n’ roll, until the ubiquitous and raunchy sense of masculine humor he popularized abandoned it. K-Rock attempted rebranding itself with pop music, but that didn’t pan out.

This was the late 2000s, and, finally, I was an old teenager. K-Rock returned, vaguely in its original form, with Opie and Anthony, Stern’s equally controversial and outlandish rivals. I’d tune in every morning during my junior and senior years, and listen to the pair—Gregg “Opie” Hughes and Anthony Cumia—bicker for my 12-minute commute. They had become notorious for their audience-driven stunts; for their most famous prank, they promoted a “100 Grand” giveaway for weeks in Boston, and, after crowning a winner, informed the guy that he was getting a free candy bar. It appealed to me, a lonely 16-year-old boy raised by idiot dudes who enjoyed this sort of thing, and I was sad to see them go. By the time I moved for college, they would leave for satellite, too. K-Rock now plays alternative music, the sorts of bands that feature wind chimes as crucial instruments.

I had missed Howard Stern’s tenure on terrestrial by a couple years, arriving to him late—his sidekick Artie Lange, who has the same wheezing cough as my old man, was already relapsing and recovering from heroin—but I arrived to him somehow nonetheless. It was probably something of an inevitability, that a kid from a working-class family of New Jerseyeans, would eventually be scouring the newly-created YouTube, searching for all these moments his father and uncles were forever talking about. Take, for instance, the “Bathroom Olympics,” an event that revolved around contestants eating inordinate amounts of food and weighing their shits for the top prize. Or take the entire Wack Pack, the group of personalities that were typically disabled, mentally ill, or afflicted with some kind of less-than-desired attribute—like High Pitch Mike, named for his unusually high-pitched voice; Jeff the Drunk, named for his chronic alcoholism; and Underdog Lady, a female performance artist who dressed as the cartoon character Underdog.

Stern was notorious for these oft-kilter on-air guests. He had on addicts, the homeless, sex workers. And he had on guys like Mr. Skin, a.k.a. Jim McBride, the amateur pornography curator, who had sifted through films in the ’90s and 2000s (and still does, apparently), documenting the scenes in which actresses are naked. Since his heyday, Mr. Skin has flown under the radar, excluding a brief but noteworthy appearance in 2007, when Judd Appatow alluded to the site in his film Knocked Up. For the unfamiliar, the characters played by Seth Rogen, Jonah Hill, and other assorted Apatow-world comedians attempt to design a similar website, unaware of Mr. Skin until they are rudely awakened to his existence.

I had forgotten him; they had forgotten him, too.

Could Mr. Skin have subsisted without men like Howard Stern propping him up? And could Howard Stern have climbed to fame had it not been for the endless boost of guests like Mr. Skin? To me, they were molded from the same clay. They were followers of a cherished and a rarely stated fact: For men, acting like a child, often at the detriment of those with more to lose than themselves, is funny.

Now we’re nearing the end of what might be their final acts. As Mr. Skin tries to justify his impact, and why he continues to operate his website (it wasn’t until 2013 that he launched Mr. Man for male nudity), he has been reduced to a reference of a bygone age in a stoner comedy. There might be worse fates. Stern, on the other hand, has taken a sharp turn into the mainstream, hosting competitions like America’s Got Talent and producing substantial conversations with singers, directors, and actors—entertainers flummoxed and energized, like himself, by Hollywood.

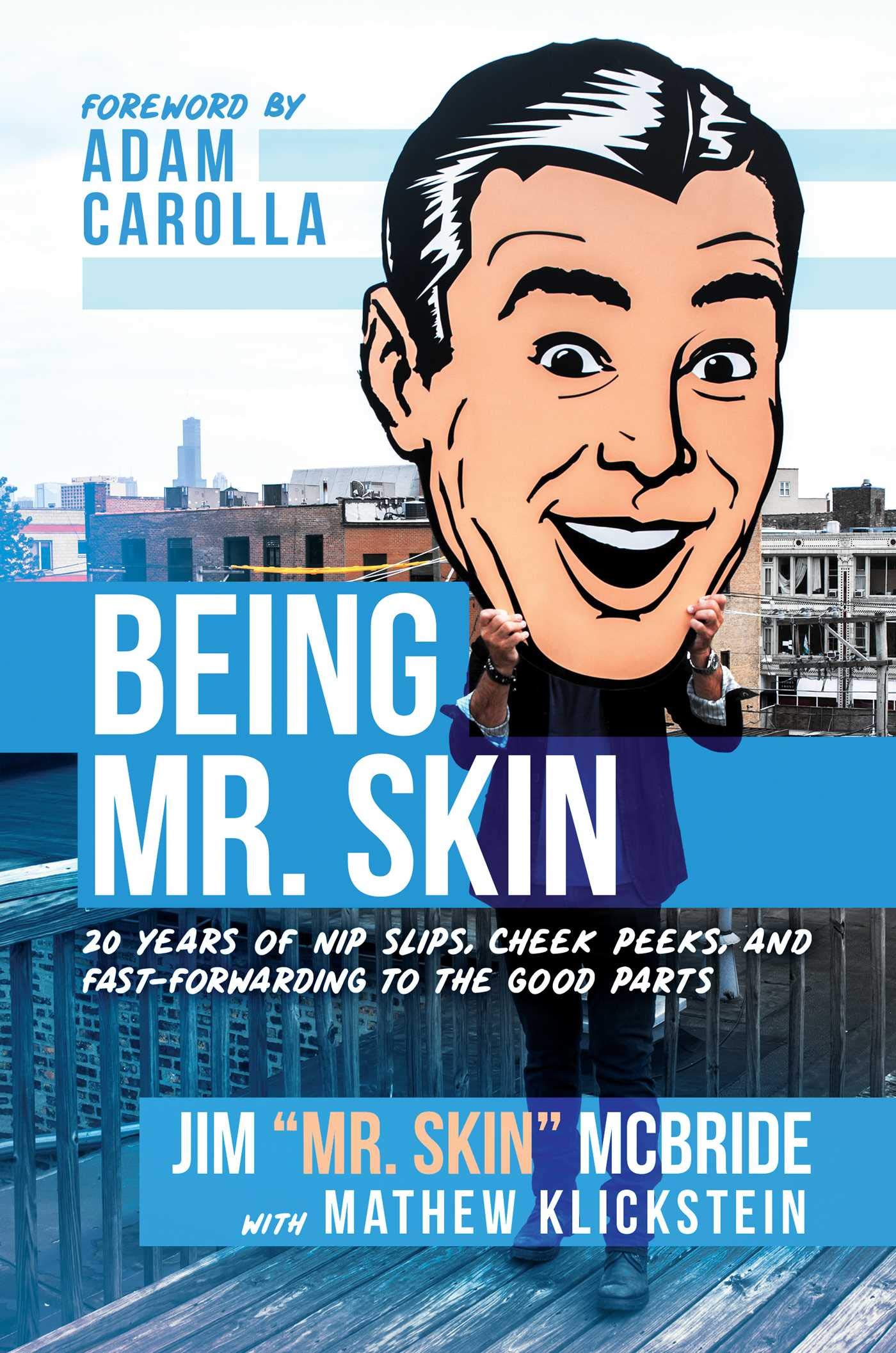

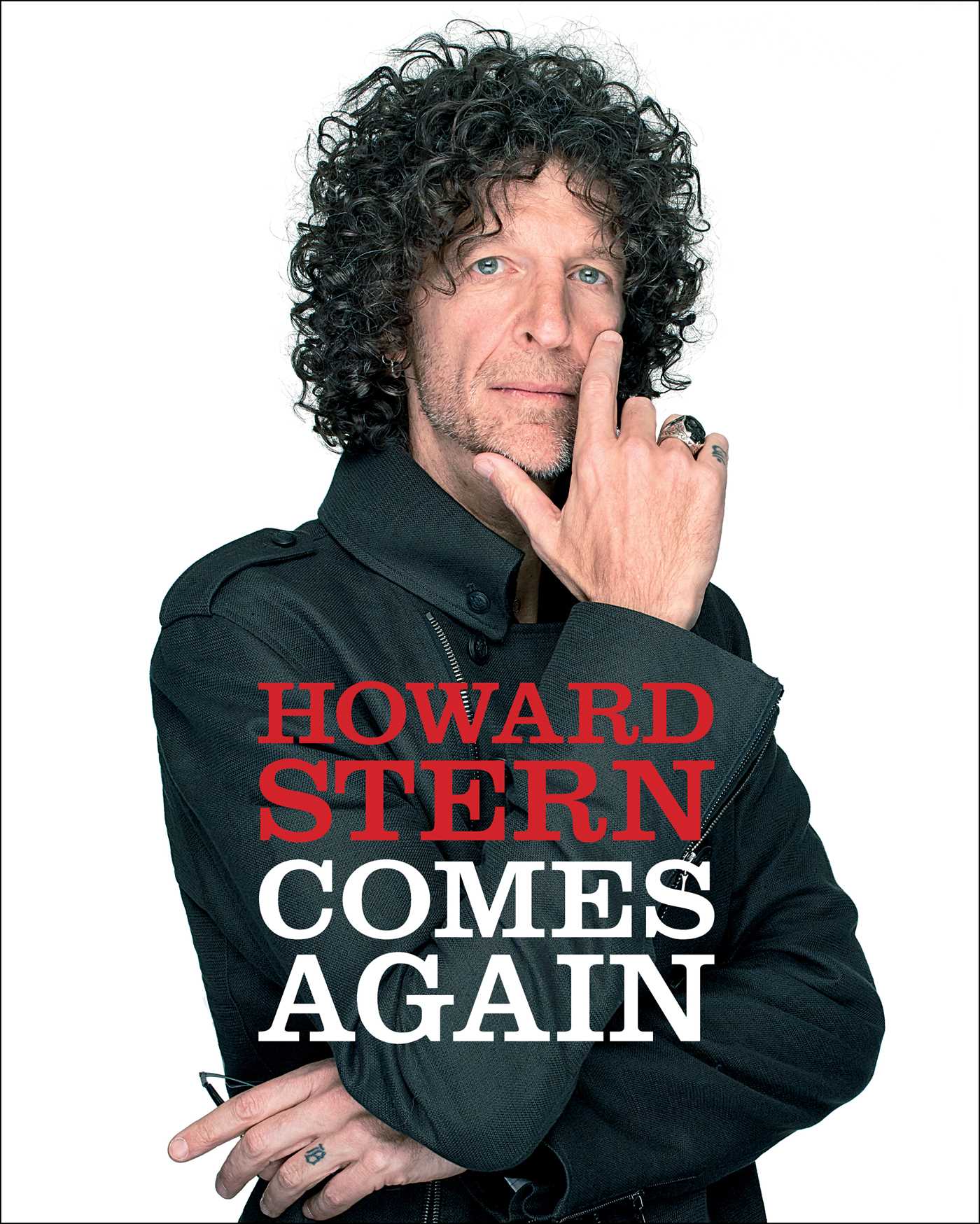

Recently, they’ve both taken to chronicling their professional journeys. Nothing says death is on your mind more than a memoir: Howard Stern Comes Again, the radio jockey’s first book in 20 years, and a collection of what he believes to be his best interviews in the past two decades or so, and Being Mr. Skin: 20 Years of Nip Slips, Cheek Peeks, and Fast-Forwarding to the Good Parts, have somehow been published within the same week.

The similar release dates of these books is either a remarkable coincidence, or a rather smart marketing technique from Mr. Skin’s publishing house. I would probably not be writing about it otherwise. Because his is nothing more than an overtly goofy play-by-play retelling, a plea to judge his work (to reiterate, a business built on identifying naked actresses on the screen) seriously, as absurd as it may be. It’s a hokey and tired coming-of-age tale (it delves into his childhood, his family, his ups and downs), interspersed with inserts like “What Was the ‘First’ Celebrity Nude Scene” and “Five Skintastic Nude Scenes That Flew Under the Radar” and “Top Ten Nude Scenes of 1999.” He wonders how he’ll reveal to his kids what he does for a living, and how much his wife supports, helps out with, and even loves his money-making venture. His memoir is a MAD magazine–esque mishmash: There are comic strips, photographs of Mr. Skin with celebrities like Jimmy Kimmel (Adam Corrolla wrote his foreword), and astounding attempts at rhyming and alliteration. You almost have to read them in awe: within the first few pages, you’ll find “volcanically voluptuous,” “massive mammaries,” and “bazooka-busted,” as well as the sentence: “So, yes, while my devotion had much to do with erections, it was also profoundly about connections.”

For younger readers, most importantly, Mr. Skin assures them that there was a period when he was incredibly important: that he began in the late 90s, in “the world before BuzzFeed and Huffington Post, and even—yes—Facebook, Twitter, and Google.” Mr. Skin was punk, you must know, “you ragamuffin millennials.” He was analog. He was before your time.

You must know this as well: Despite somewhat distancing himself, Stern was squarely in the very same universe—and even, lest we forget, helped give rise to Mr. Skin himself. Mr. Skin recalls the second “skinfining moment” of his life all too well.

“It was probably the best thing that ever happened in my professional life,” he writes. “I can still remember the exact minute: It was 8:20 A.M. on March, 23, 2000, that I was asked to be on Howard Stern’s radio show and happily accepted the lifesaving invitation.”

Whatever we end up rewarding Stern in the annals of history, we’ll be left, like him, having to deal with his whole legacy, considering whether his past of thoughtlessness was necessary for him to leap into his present of thoughtfulness.

Stern, shockingly, doesn’t include this interview in his own book—nor what Mr. Skin insists were additionally “at least twenty-five [more] mind-blowing times”: “He loved me so much,” Mr. Skin writes, “that he recommended that all his listeners go check out MrSkin.com for themselves.” He spends nearly 15 pages, in one form or another, thanking Howard Stern, especially for letting him kick off his annual Anatomy Awards, which are “timed to come out with the Oscars,” and are precisely what you think they are: they celebrate “all the best nudity in the year’s films, [television shows], and—nowadays—web/mobile series.” (The promotional copy on the back of his book mentions Stern, too, as does the actual website. He last appeared on The Howard Stern Show in March of 2018.)

“Me being on Howard Stern,” Mr. Skin concludes, “practically broke the site.”

This might be the most useful context to gain, reading Mr. Skin and Howard Stern Comes Again side by side: how differently the two regard each other. I may have forgotten, or never known that much, about Mr. Skin, but I had somehow both forgotten and forgiven Howard. It wasn’t a conscious lapse—but this exercise made it so.

I do have an inexplicable soft spot for Howard Stern; you’d be hard-pressed to persuade me that he is not among the most fantastic interviewers ever: His conversation with Conan O’Brien, which he himself lauds as his best, marvelously delves into anxiety, depression, and the perils of success and failure; his one with Jon Stewart goes, deeply, into the former Daily Show star’s estranged with relationship with his father; and his discussions with people like Lady Gaga and Gwenyth Paltrow will sincerely give you a brand-new perspective on both of them. (Honestly, you could flip through the pages at random, and you won’t be disappointed. Donald Trump, of course, is included.) Stern deserves credit for who he has evolved into—a thoughtful, smart, introspective, and pretty hilarious man, who does his research, has no difficulty asking the tough questions, and possesses enough self-awareness and self-criticism to appear, relatively, genuine.

“I’m not proud of my first two books,” Stern writes in his introduction, of Private Parts and Miss America, Lenny Bruce–style autobiographies that deal with his adolescence, his seminal influence in the radio industry, and his flatulence. “I don’t even have them displayed on my bookshelf at home. I think of them, and of the interviews I did with my guests during those first couple decades of my career, and I cringe. I was an absolute maniac. My narcissism was so strong that I was incapable of appreciating what somebody else might be feeling.”

Generally, Stern is not known for his modesty, so this is, perhaps, extremely telling. (Juxtapose that with his commentary about the contentious director Vincent Gallo from 2005, in which he notes: “I recognize it is some of the greatest radio ever done—not merely the greatest radio I’ve ever done but the greatest radio in the history of the medium.”) You do not need to—nor should you—read Howard Stern Comes Again in a single sitting. As he claims, he might not be as self-obsessed as he used to be, but there remain bright—nearly blinding—flickers of an ego. He wouldn’t have written this book, he admits in the intro, had an editor at Simon & Schuster not essentially bound through his apartment door with a finished copy already in hand. But that wouldn’t do—partly blaming his OCD, and partly blaming a pursuit of perfection he won’t apologize for (“That’s my problem: Everything has to be perfect”), Stern tinkered with the book for close to two years.

I do believe Stern. I do believe this hefty, quite beautiful coffee table book should be combed through more than once. I do believe he is not the same person he once was—a shock jock with a foul mouth, blasting construction workers awake on their commute. I do believe people are capable of profound change, and he and Mr. Skin are, well, not the same. (“I had always wanted to do interviews that had substance,” Stern told David Marchese in the New York Times Magazine. “The problem was that, in the old format [of terrestrial radio], you couldn’t.”)

But whatever we end up rewarding Stern in the annals of history, we’ll be left, like him, having to deal with his whole legacy, considering whether his past of thoughtlessness was necessary for him to leap into his present of thoughtfulness.

Other than Stern, I cannot think of anyone else who has so seamlessly undergone such a cultural transformation. Especially while maintaining—or even, at times, gaining—the respect of his colleagues and peers. While Mr. Skin was recording Tara Reid with his VCR, Stern was also putting out episodes of The Lesbian Dating Game. But, now fast-forward two decades, and Stern is on The View, as part of his recent publicity tour, reiterating how sorry he was for how he mocked Rosie O’Donnell over the years, and chastising some of the hosts for how they’re now treating Meghan McCain. Stern’s newer interviews are akin to therapy sessions, and therapy is something that Stern likes to speak about a lot.

He hopes we’re here to talk it out with him.

As a kid, I never realized, or, in keeping with a pattern, just naïvely forgot, how much of Stern’s influence had antagonistically permeated the American zeitgeist. During a police raid at Michael Jackson’s Neverland Ranch, after the family of a 12-year-old boy filed a report alleging the musician of “criminal activity,” a prank phone caller dialed into Fox News masquerading as a spokesperson for the Santa Barbara Sheriff’s Department. Following 30 seconds of solid acting, as if reading directly from a script (“Mr. Jackson has not been charged with any crime”), he uttered his punch line: “We cannot specifically address the content of the police report as it is confidential information at the present time; however, we can confirm that Mr. Jackson forced the boy to listen to The Howard Stern Show and watch the movie Private Parts over and over again.” After three people were arrested in connection with starting a fire in San Diego, an inferno that looks eerily reminiscent to those plaguing California now, somebody placed a similar call to CNN, having convinced the screeners he was Dick Murphy, the mayor of the city: “We don’t want to give their names out, or anything like that, but the fires were started by a blast of wind from Howard Stern’s asshole.” In 1996, capitalizing on the media frenzy, Stern invited John Wayne Bobbit on to discuss his penis enlargement surgery, after his wife, Lorena, had chopped off his genitals. And, in what’s been referred to as one of the greatest phony phone calls in history, a fan known as “Maury from Brooklyn” dialed into ABC during the infamous O.J. Simpson White Bronco car chase and claimed to be a witness on the scene (“I see O.J., and he looks scared.”)

We’re currently in the midst of a reconsideration of those events—series-length documentaries have examined decades of Michael Jackson and his apparent sexual assault of minors, and Lorena Bobbit’s own years of abuse at the hands of her husband. The California wildfires have turned into a potent, never-ending example of the climate crisis we seem to forever be avoiding. Meanwhile, Mr. Skin is reconsidering why he never adapted to the whims of the world. (He did, however, stop wearing his signature Hawaiian shirts.) Stern is—nonstop—reconsidering himself.

“I just spewed all my angst and bile into the microphone,” Stern writes about his “early career,” in the introduction to his Gallo interview. “I would let it all out. We’re seeing that today in all corners of society. The more extreme you are, the more attention you get—the more likes and retweets and comments. I understood that formula long before the internet existed.”

He understood why people once marveled Mr. Skin, but he was smart enough to understand why they don’t, necessarily, publicly embrace him any longer.

The other day, I asked my dad if he planned to purchase Howard’s new book. He doesn’t pay for Stern on Sirius, he says. He never did. He abandoned him following his shift to satellite, and his philosophical transformation. But whenever Stern does come up, which isn’t infrequently, it’s always the same. My father, from memory, impersonating the ever-so-serious and professional broadcaster Al Michaels, when he informs his colleague that the on-the-scene dispatch from the alleged O.J. bystander was “a totally farcical call.”

“Lest anybody think that that was somebody who was truly across the street, that was not,” Michaels says. “He said something in code at the end that’s indicative of the mentioning of the name of a certain radio talk show host.” Baba Booey to you all, the caller had uttered, referencing the nickname of Gary Dell’Abate, Stern’s longtime producer.

Listening back, it reminded me how easy it can be to pretend, how easy it is to ignore what’s right in front of your face.

It reminded me how funny that used to be.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Alex Norcia on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.