Erasure Poets Are Turning the Heavily Redacted Mueller Report into Art

Credit to Author: Adriane Quinlan| Date: Fri, 19 Apr 2019 12:52:08 +0000

The readers who trudge through Attorney General William Barr’s version of the Mueller report on Thursday will be forced to navigate its redactions. Skimming past the great blocks of unknowns can be a bizarre, new reading experience for almost everyone except investigators, journalists, and fans of a certain genre of literature that tends to blossom in times of high-profile redactions—and, coincidentally, has never been more popular than it is now.

Erasure is the softer, snobbier name for a form of poetry made by whittling down the words in a found document. It’s now more commonly known as “blackout” poetry, a label that pays homage to its similarity to a redacted court filing. The first experiment with erasure came about in Britain in 1966, when fiction was still being censored, and a dry, dull Victorian novel seemed to primly beckon to the artist Tom Phillips, calling on him to reverse the censorship process by pulling out its luscious moments and covering the rest with wild color.

If Instagram poets are now pushing for erasure’s revival, that might be because it tends to pop up in “a kind of society with a culture of suspicion—a suspicion that things are being held and withheld from individuals,” said Srikanth Reddy, a poet who works in the form. “It’s almost always kind of motivated by political concerns.”

Concerns, like the redaction of the Mueller report. “Oh I’m going to read it, sure,” said Travis Macdonald, who erased down The 9-11 Commission Report to publish a book-length erasure titled O Mission Repo in 2005. “A lot of folks in the erasure community—we’ve all exchanged notes on the subject.”

Jerrod Schwarz, a member of that community, put it bluntly. “It’s our generation’s 9-11 Commission Report.”

To them, Barr’s redactions won’t just leave us without key tidbits or details to shape a new story; they’ll make an argument by virtue their sheer existence. Macdonald’s erasure of The 9-11 Commission Report uses black bars and white space to leave behind a mournful analysis of capitalism, politics, and “errorism,” that speaks to how easy it is to shape a new story out of a complex reality—a process that got us from Lower Manhattan to Iraq.

“The Mueller report being issued with redactions would actually reveal the silencing, or the silences, more than any unredacted report would,” Reddy said. “The more black there is, the more political impact it will have. A redacted text can have the opposite effect than the censors want it to.”

That effect will make us more aware, line-by-line, of other ways that the government keeps us in blinders. “There’s been erasure before this becomes official,” Macdonald said. “Erased or reclaimed by the work the Trump administration has done to, in effect, discredit the whole thing.”

“I’m a newshound,” said Janet Holmes. “Whenever I see a redacted document on TV or on the news, it seems as if we’re all enacting or participating in some sort of act of poetics.”

Holmes re-worked The Collected Poems of Emily Dickinson into The ms of m y kin (2009) to extract a war narrative that evokes both the Civil War that Dickinson lived through and the conflicts in the Middle East that Holmes did. Looking at a Mueller filing on Michael Cohen, she noticed how language used to avoid “reputational harm” (as Barr would put it) can make the government seem like a prim old-world columnist who delights in describing gossipy exploits.

An erasure poem may look like a redacted document, but it has the opposite aim: to elucidate a hidden truth, not hide an obvious one; to create something new, not just remove what’s there. Still, redacted documents can be a hoot to read for poets who make the same decisions about which words to keep or cut.

“The characters all have names like ‘Individual 1’ or ‘Firm A.’ It’s almost like reading one of those novels where the characters are named with a letter and a dash,” Holmes said. “I think of Victorian London.”

In other ways, redactions can reveal the human hand behind them—whether they are prosecutors or artists. “A very tiny detail that shows you a human went through and did this,” said Schwarz, who’s been erasing Trump’s speeches and The Art of the Deal. “In some cases they keep a letter, a comma. This is why I get excited about the redactions; you can’t take the humanity away,” he said. “This was somebody’s job.”

Redactions can also have an emotional effect. “They seem much more resistant than a blank, white page,” said M. NourbeSe Philip, who chose to selectively blank out, rather than black out, the only existing record of a slave massacre for her book Zong! (2008). “I get the sense it’s intended to keep you out, keep the reader out.”

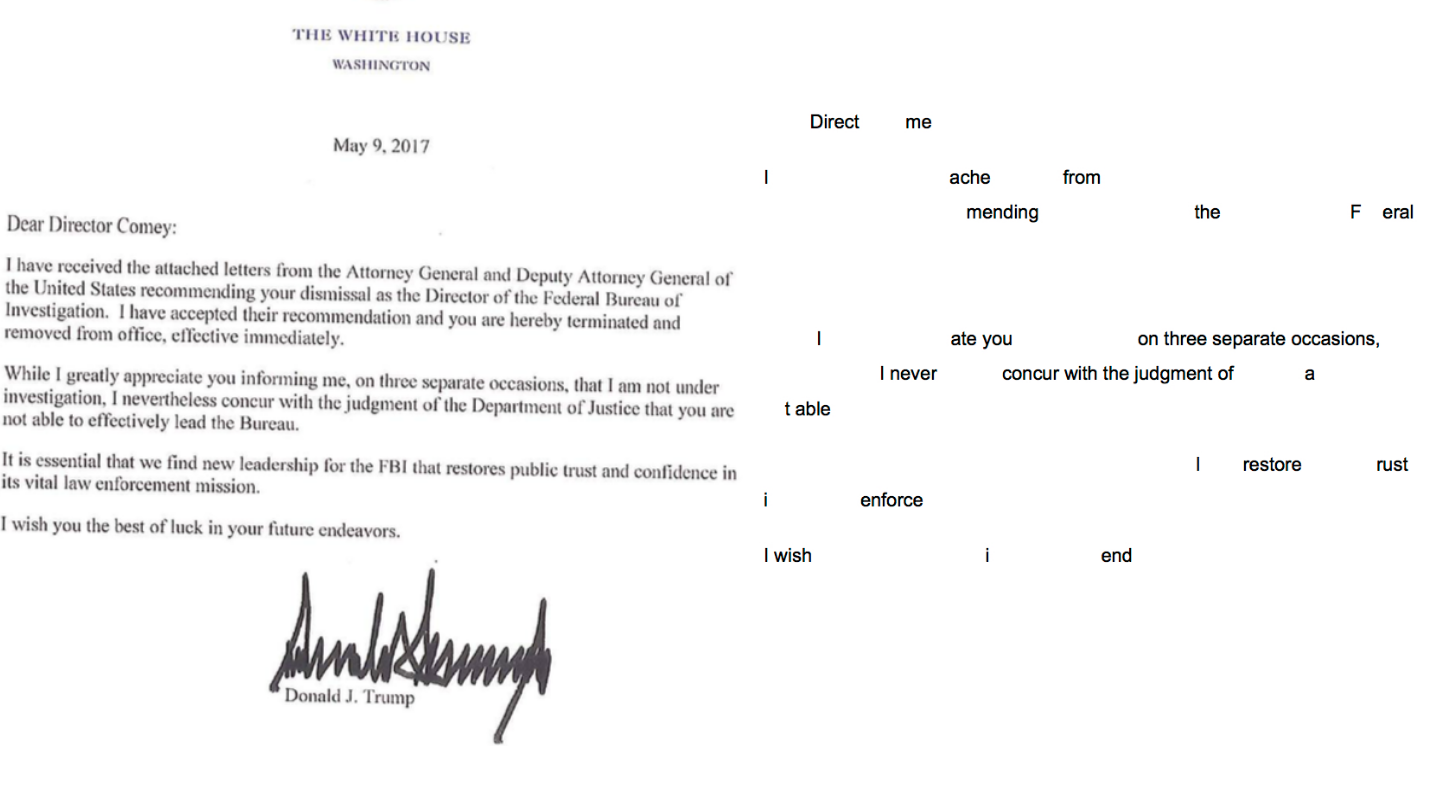

On the left is Donald Trump’s memo firing former FBI director James Comey, on the right, Jerrod Schwarz’s erasure poem made from the document.

“This is a perversion of what I do,” said Schwarz of a supplemental memo to the sentencing recommendations for Michael Flynn. “That said, if a student brought me this I would be thrilled.” The reason: he was drawn to page four of the Flynn supplement where, preceded by five redacted lines and followed by eleven more, hangs a useless, castrated phrase: “The defendant also provided useful information concerning.”

“The ‘concerning’ makes it incomplete,” Schwarz said. “That’s another thing erasure can do, is make you feel the presence of what you are removing. Concerning could mean ‘of concern’ to people, it could be a ‘concerning matter,’ and certainly it is.”

“The little bits of language left between the redactions were just gorgeous and so non-specific,” said the poet Kenneth Goldsmith. “Concerning what? Concerning everything.” Goldsmith considers most documents—redacted or otherwise—poems in themselves. He infamously read Michael Brown’s autopsy report and will present 60,000 of Hillary Clinton’s emails at a show during next month’s Venice Biennale. “What the redaction does is it universalizes the document,” Goldsmith said. “It’s no longer about Flynn, it’s about all of us.”

Erasure poems tend to show us how much of our world is made up of redaction: how everything we see, touch, read, wear, and nibble was created through selection by cutting, refracting, withholding, reducing, commercializing, and making smaller from a wider, more complex strata of possibilities. In the way an Impressionist painting reveals its brushstrokes and modern architecture its girding, erasure reveals the selection process behind all language and all storytelling, and it tends to pop up when people are wary of what’s being chosen for them.

“That seems like the defining feature of America, right now: we don’t get to know the whole truth,” said Schwarz. “This is art imitating society,” he said. “It’s meta, in the most depressing way.” His work is part of a forthcoming political erasure anthology (Erase the Patriarchy), and he wrote the introduction for an activity book for would-be writers (Make Blackout Poetry: Activist Edition). If he tends to think the genre can be activist, that’s because he thinks of an erasure as a way of doing to the government what it does to us. “I am owed a conversation with what rules me,” he said. “Political erasure is all about the flip: doing the opposite of what a large, powerful government is doing.”

If erasure is everywhere now, that’s because we’re all quite aware of what the government is doing, said Holmes. She was amazed to see Alec Baldwin on a recent episode of Saturday Night Live doing what she’d done with Emily Dickinson’s poems. As Trump, Baldwin redacts a copy of the Mueller report to leave only the words “no” and “collusion” swimming in black lines. “I thought, if that’s entered the public consciousness as much as to enter SNL as a joke,” Holmes said, “Then it really is in the public consciousness.”

“In the Trump era, I think people are angry and pissed off at documents,” said Goldsmith. “They look to documents for efficacy and justice which is great, but that’s not poetry’s work—efficacy and justice. Poetry works in the opposite way. It makes nothing happen.”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

You can follow Adriane Quinlan on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.