How the World’s Prisons Look From Within

Credit to Author: Laura Woods| Date: Wed, 13 Mar 2019 13:21:48 +0000

Some 10,350,000 people are currently held in prisons worldwide, according to the advocacy group, Penal Reform International. Every year this non-for-profit examines the state of incarceration around the world and releases a report. And last year’s report can be summarised with this single damning quote:

“Detention conditions are degrading, the number of prisoners is increasing while the overall level of crime is declining in a majority of societies.”

This, of course, is a sad indictment on the universal popularity of tough-on-crime politics. So many justice systems around the world are working at capacity, which for most voters is just fine because they’re not seeing the result. Most of us have never been in a prison, so we don’t see the ubiquity of crumbling infrastructure and cells designed for singles crammed with several. We’re blind to how our votes directly affect society’s poorest and least educated, so we don’t care. And so the downward spiral continues.

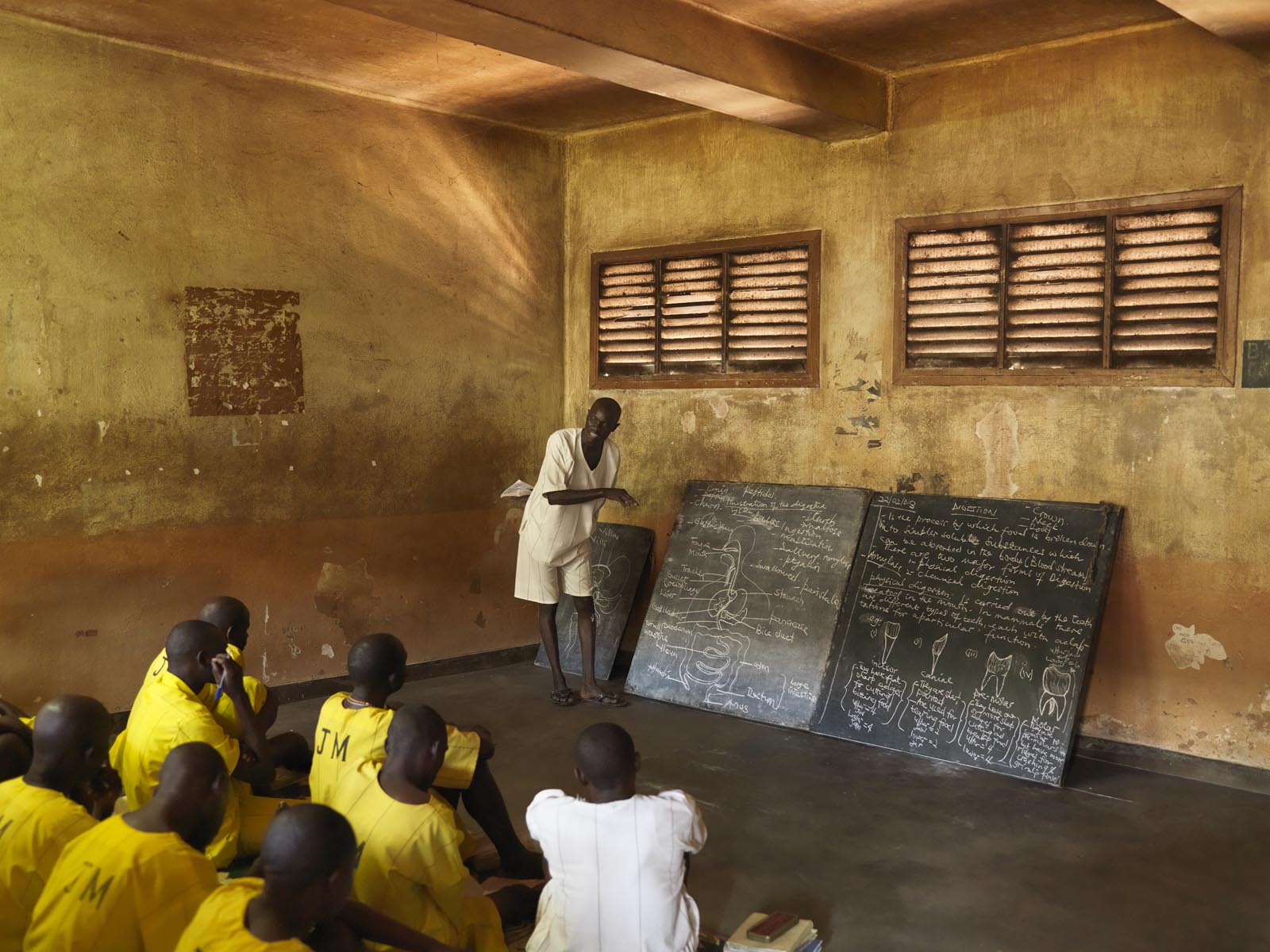

Hoping to contribute to a much needed reevaluation of our globally trigger-happy legal system, Dutch photographer Jan Banning undertook the seemingly impossible task of photographing prisons around the world. By travelling to Uganda, France, the United States, and Columbia, Jan’s photos invite us to question whether prisons are really achieving their purpose—to correct, rehabilitate, and deter.

Speaking to VICE from his home, Jan explains how he got access to these places, what he saw, and in the end what he learned about criminal reform around the world.

VICE: Hi Jan. Can you first tell us a little about what these photos are trying to tell us? Why these countries? Why, for example, are we comparing a prison in Uganda to a prison in France

Jan: Good question. Firstly, I asked myself oh, where can I take nice photographs? This would probably have left me with a nice photo book but where is the relevance? What would it mean? It was always my wish that my work played a role in the public debate.

So with help from the Max Planck Institute, I decided to focus on countries based on a few different metrics: firstly a division between civil law and common law, a consideration of their geographical nature, and just how important these countries are internationally. So then I choose two examples of each of the two main versions of criminal law: one Western example (civil law in France and common law USA) and one non-Western example (civil law Colombia and common law Uganda). I also decided to photograph the US rather than England, because the US has the death penalty, which is, of course, the most radical system that exists.

What was the easiest prison to access?

Remarkably, by far the easiest to access turned out to be Uganda, I think due to probably the liberal ideas of the Commissioner of Prisons there who is a very open and transparent person.

And what were the others like?

The others were kind of a nightmare. France took me about two years to get access to the prisons. The US took me a little less than two years, and with Columbia the first round in medium and low-security prisons was doable. But when it came to the next trip, to take photos of the high-security prison, they cheated me. After a lot of hassle writing applications they gave me access to four maximum security prisons, but once I was there they stopped me from photographing anything but the nonsensical English lessons that took place in rooms that nobody was even in and in a workshop where they were doing some nice woodwork. It was still terribly dirty and overcrowded, but there were areas where if I just looked through my camera lens, I was surrounded by guards that physically stopped me from photographing. As well, in Columbia, generally judges didn’t want to be photographed because it was risky for them.

Was there anything particularly surprising or shocking that you uncovered when photographing the four different systems?

What really struck me was that the atmosphere was by far the most relaxed in Uganda. Out of all of them, the atmosphere there was probably the best. Ugandan prisons though, they’re still not like hostels. They’re overcrowded, there’s a lot of poverty but at least generally, they seem to be treated well.

I would say France, materially speaking, was the best of all four. They can have a lot of things in their cell, they can cook for themselves too. I would say incarceration in France is tolerable, speaking in relative terms. Those two systems struck me as relatively humane.

What I found very interesting is that the contrast is also very visual, which was a lucky coincidence for me. If you look at the photographs from Uganda, there’s a lot of warm colours. They use a lot of yellows, like an African village. Whereas in the US it’s all stainless steel and concrete and cold. It had a lot more depressing feel.

I became friends with Uganda’s most famous prisoner, who has since been released and who spoke at my Law and Order exhibition in Germany. She totally confirmed my impression that the relationship between guards and other prisoners in Uganda is really nice, which I didn’t expect at all. Even though I have been through a lot of places in the world over a 37-year career, I really expected the prisons in Uganda to be worse, and I expected the prisons in the US to be better. Those two countries surprised me the most.

What surprised you about the US prison system?

Well, I’d say that the prisons in the US were institutionalised punishment, despite the fact they were under the Department of Corrections. I think first and foremost, US jails are designed to be punishment.

Were you allowed much interaction with the prisoners in any country?

I did interact with them in Uganda. The photograph of the man sunbathing in between the nicely coloured walls in France, he was a mafia boss from Corsica. We talked for maybe half an hour or so. In Columbia, I was mostly prevented from talking to people. Same with the US.

How would you like the comparative series to contribute to public discussion surrounding systems of incarceration?

I didn’t necessarily set out to prove that one was better than another, that was not my starting point. Clearly, in the end, I have preferences.

The correctional services and the way we handle crime seems to play a big role in the politics of many countries, and even more so than a few decades ago due to the rise of populist parties and this idea that how we punish people will determine how we bring down the crime rate. In the book, I present comparisons of crime and murder rates in several parts of Europe, which have gone down enormously. The world is a much safer place if you look at murder rates over the years. The world is safer than it ever was, maybe with the exception of the 1950s and 1960s and I think many people are not aware of that. I hope that the book will be a contribution to the public debate about how we handle crime. I think comparing different systems, situations and cultures is always a very good way of getting perspective.

You talk a little bit about why you don’t think incarceration is particularly effective in a lot of cases. Why so? Do you feel like there could potentially be an alternative to the current system of incarceration?

I have strong doubts about the use of the prison system in general. I know that in some cases it’s necessary to isolate people from society. Some people just aren’t fit to participate in society, but I think that’s a minority of the incarcerated people. I think a lot of them are people who have bad luck, who never had a chance, who may have mental problems, who belong to the lowest class, and race plays a role. I think this focus on punishment, is not the best of ideas. I think correcting them and giving them opportunities to live a life that contributes to society is a much better idea, and that may well have to do with my own background. In Holland, incarceration rates are so low that we’re actually renting out prisons to Norway and Belgium.

Interview by Laura Woods. All photos by Jan Banning

This article originally appeared on VICE ASIA.