Downtown Manhattan in the 1970s Was New York’s Golden Era for Nightlife

Credit to Author: Dan Q. Dao| Date: Fri, 22 Feb 2019 19:54:51 +0000

This article is part of a special installment of Deep Dive created in partnership with Jameson Irish Whiskey, telling the stories of bars of yesterday that shaped the neighborhoods of today.

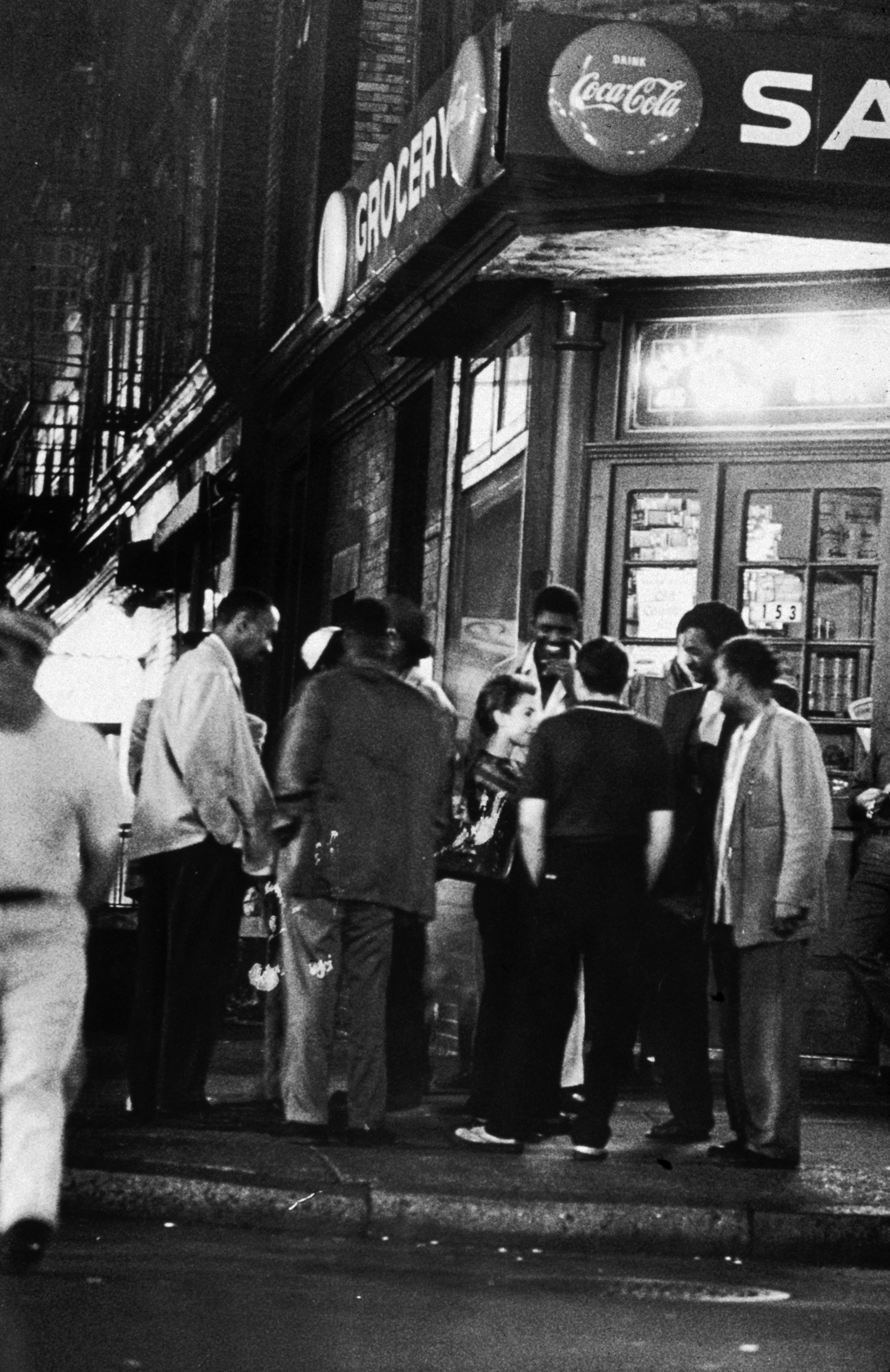

There will always be those storied bars and clubs that speak to the zeitgeist in which they thrived—spaces that synthesize the creative essence of their patrons, and by extension, society. And if we’re talking about New York City, there may never again be a nightlife scene as representative of the city’s freewheeling spirit as downtown Manhattan in the 1970s.

It’s easy to see why we continue to talk about this legendary decade. When remembered through the rose-colored glasses of nostalgia, the 70s represent the last vestige of New York history in which the city might have been considered egalitarian—when it didn’t matter whether or not you were wealthy, as long as you carried yourself like a star. It was a time when cheap rent meant the artistic class ruled downtown Manhattan, before MTV (and, later, the Internet) commercialized the underground and its creative output.

“Back then, everyone wanted to be fabulous; everyone wanted to be someone,” explains musician Bebe Buell, who, at 18, moved to New York to become a model. “We all gathered together with the same dream.”

It was in the fabled back room at the restaurant-nightclub Max’s Kansas City, opened in 1965 by Mickey Ruskin, that Buell would eventually meet the rock stars for whom she’d famously serve as a muse—among them: Mick Jagger, David Bowie, and Steven Tyler, who gave her a daughter, Liv. On her fateful first visit to the venue, located in what was then considered a no-man’s-land, at 17th Street and Park Avenue, she remembers being captivated by a red light glowing from a mysterious room. She later returned to the club to see what was inside. Looking around at a room full of the city’s creative elite, Buell did not yet realize the world she was about to enter.

“Lou Reed was very kind, and invited me to come and sit with him and his date. That was also when I met Andy Warhol, who was so charming and funny,” said Buell, then a teenager fresh from Virginia. “He took one look at me and asked me if my parents bred horses!”

Danny Fields, manager to Iggy and the Stooges and The Ramones, recalls the rise of Max’s, which supplanted predecessors, like CBGB’s, to become the city’s preeminent rock-music destination, opposing the disco-centric glamour of uptown clubs like Studio 54.

“The people in the front—they were what we called the ‘abstract-expressionist heterosexual alcoholics,’” laughs Fields. “But at the glorious height of Max’s, the beating heart of the joint was the back room. All the musical people moved back there.”

“It was just a moment in time where it didn’t matter what you were doing, whether you were an artist or whatever,” Holliday continued. “We knew everything happened at night.”

By the late-70s, Max’s was under new management, catering more to New Wave and punk in the spirit of the older CBGB’s. With a generation of kids who’d come of age at the height of these institutions, the underground music scene was given new energy.

Enter the now-defunct Club 57.

Along with its sister club, Irving Plaza, the still-thriving concert hall, this cramped, DIY venue, housed in a church basement on St. Mark’s Place, initially sought to fill a void for the alternative crowd, where any artist could rent space to showcase their more experimental ideas. Eventually, it would become an incubator for the artwork of Klaus Nomi, Keith Haring, and Jean-Michel Basquiat, as well as a stage hosting the likes of Madonna and Cyndi Lauper.

“It started with everybody downtown—it was all the misfits, the artists, filmmakers, actors, choreographers, painters, photographers, heroin addicts, and everyone who was alternative,” says Frank Holliday, an artist who’d designed many of the club’s early sets. “It was just a moment in time where it didn’t matter what you were doing, whether you were an artist or whatever,” Holliday continued. “We knew everything happened at night.”

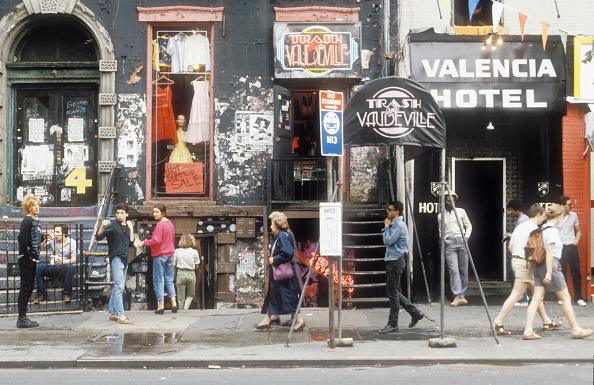

Club 57’s sparse, no-frills digs and eclectic entertainment, including debutante balls and pop-up art galleries, were a nod then to the anything-goes culture of its environ: the East Village. Though often overshadowed by its contemporaries—there’s no mention of it in ‘The Warhol Diaries’—it became a standard bearer for transgressive nightlife spaces inextricably linked to the art being created both inside its walls and beyond them.

As higher-end galleries and studios began taking over SoHo, the East Village became the next destination for young artists and musicians. At the time, the area was largely run by Eastern European immigrants, with dive bars like Sophie’s and Lucy’s—both timeless institutions, which have survived to the present day—dotting the map. In a precursor to today’s sweeping gentrification, artists began taking over the neighborhood’s tenement buildings.

“The people who would go to Club 57 were the people who lived in the East Village,” remembers photographer-artist David Schmidlapp, whose innovative light projections were turned into slideshows featured on the club’s walls. “It was the cheapest place to live. People didn’t come for careers; they came to do their thing, [to] do their art.”

For Schmidlapp, the act of going out was not just about gaining facetime with peers; it was a part of a larger persona. If you wanted to be an artist, nightlife beckoned. “You did not have to be some guy showing a gallery, or a fashion model,” Schmidlapp recalls. “You could be anyone who did ‘art.’”

Schmidlapp’s moving artwork earned him airtime at the Mudd Club, the loft-nightclub in TriBeCa opened by provocateur Steve Mass. While Club 57 and the Mudd Club co-existed in the exact same years—1978 to 1983—the latter launched in larger digs with more mainstream appeal. Part concert hall, part art gallery, the two venues would share similar ethos and crowd, as Mass promoted popular artists to win over the downtown scene.

“There was no separation like there is today, meaning certain clubs for certain types of people.”

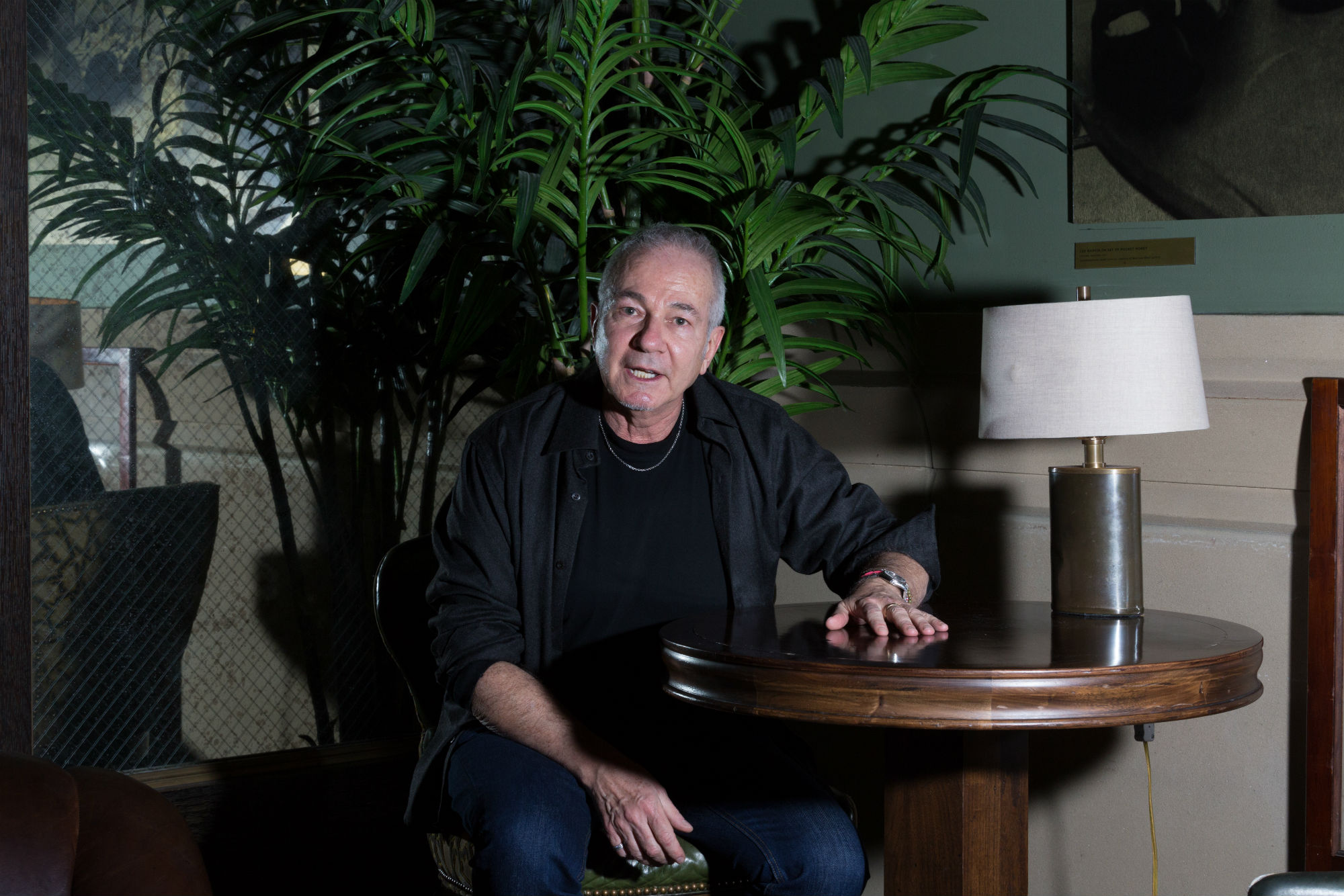

In his acclaimed memoir The Mudd Club, Richard Boch, the club’s one-time doorman and an artist in his own right, describes how a creativity-first mentality turned the club into a breeding ground for counterculture. It seems unheard of now, as social media favors calculation over spontaneity: a place, according to Boch, where Mass might, without hesitation, approve an art installation that involved putting guests in cages.

Working as a doorman, Boch sought to let in the kind of revelers who represented that forward-thinking spirit. “Whether it was the Mudd Club, or Max’s, or CBGB’s, or even Studio 54 to a degree, it was all about the mix of people,” Boch explains. “There was no separation like there is today, meaning certain clubs for certain types of people.”

Towards the end of the Mudd Club’s reign, nightlife grew commercialized, and the allure of the underground waned. Newer, glitzier venues began popping up across town—including Danceteria, Area, and Palladium, a live-music venue transformed into a glam club by Studio 54 hitmaker Ian Schrager. (It’s now a New York University dorm.) Even Club 57-goers realized times had changed when they began receiving VIP treatment at other venues.

“I remember Keith [Haring] curated a show, and a lot of heavy-duty art world people came in,” recalls Holliday. “There were dealers from SoHo—real movers and shakers. They showed up and started making the artists stars, so it went in a commercial kind of [direction].”

There are still some who obsess over the nightlife of this bygone era. Maybe because it felt like a precipice, before things changed forever: the AIDS crisis would soon shatter the scene, claiming the lives of countless participants, and America lurched rightward in the Reagan years. It seems only natural to long for a time when apartments could be had for as little as $150 a month, even if such glossy narratives ignore a city overrun then by crime and urban decay.

“We’re dealing in mythology now, and mythology is always bigger than life,” Schmidlapp says. “When you get down to it, it was dirty and gritty and competitive… We had fun, but it wasn’t all this constant party.”

While that downturn created the low prices that drew those would-be artists, musicians, and designers to New York, it was places like Max’s Kansas City, Club 57, and the Mudd Club that made for its shared experience, helping to usher in a force of creative power that defined a decade. And perhaps it’s that urge to party on—to hold on to the glimmer of hope, that anything could happen at night—that still represents the city’s enduring spirit, even today.

“It created a sense of community with incredible energy, where people were doing a lot of things,” Boch concludes. “They weren’t just talking about becoming stars; these weren’t just pipe dreams. It was very do-it-yourself, and people were fearless then.”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Dan Q. Dao on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.