Students Can Help Lecturers Break Their Mafia-Like Work Conditions

Credit to Author: Tom Whyman| Date: Thu, 21 Feb 2019 15:02:30 +0000

Welcome to Universities Challenged, a column about the world of academia.

Working in academia is like working for a cartel. A few years ago, a political economist named Alexandre Afonso suggested that hiring conditions in academia resemble those of a drug gang. The idea is that both are structured around “an expanding mass of outsiders and a shrinking core of insiders”, a set-up known by labour market scholars as “dualisation”.

In both academia and drug gangs, the people at the bottom, who do most of the work – taking seminars, marking essays, standing on street corners pushing dope – experience low pay and endure incredibly insecure working conditions (although in only one of these two industries does that mean a greater possibility of being shot).

The mass of outsiders grin and bear these working conditions because they dream of one day making it to the top – whether as a tenured professor, or as a “made guy” in the mob. Once you’ve made it to the top, you’ll have a great job: a high salary, academic freedom, recognition from your peers – or just an effective licence to print money. Your position also becomes relatively hard to shift: in both industries, there are all sorts of structures protecting the guys at the top. In other words, academia is like a drug gang because the desirability of the top jobs works to make the bottom jobs a lot worse.

It’s fair to say that pay and conditions in UK higher education are not good. According to findings by UCU, the lecturers’ union, academic pay has declined by 21 percent in real terms since 2009. Casualisation – reliance on insecure, low-paid employees – is rampant, with some universities using hourly-paid staff to deliver up to 50 percent of their teaching (the average figure is 27 percent). A 2015 report found that 40 percent of university staff on insecure contracts earned less than £1,000 per month, with almost a fifth saying they struggled to pay for food, and almost a third saying they struggled with their rent or mortgage payments.

Workload is also a big issue. Typically, academics are contracted to work 37 hours per week. A 2016 report found that, in practice, they work on average 50.9 hours per week – almost two whole extra days. More than a quarter of staff were found to work more than 55 hours per week, with Research Fellows and Teaching Assistants (i.e. entry-level staff) among the most affected. A whopping 83.1 percent of staff had felt their workload increasing over the past three years, with 65.5 percent stating that they felt their workload was “unmanageable”. Unpaid additional work by staff is worth an approximate total of £374 million per year – all of this effectively pocketed by universities.

Aside from being very bad for entry-level workers in terms of pay and conditions, dualisation also makes it difficult for them to organise to improve things.

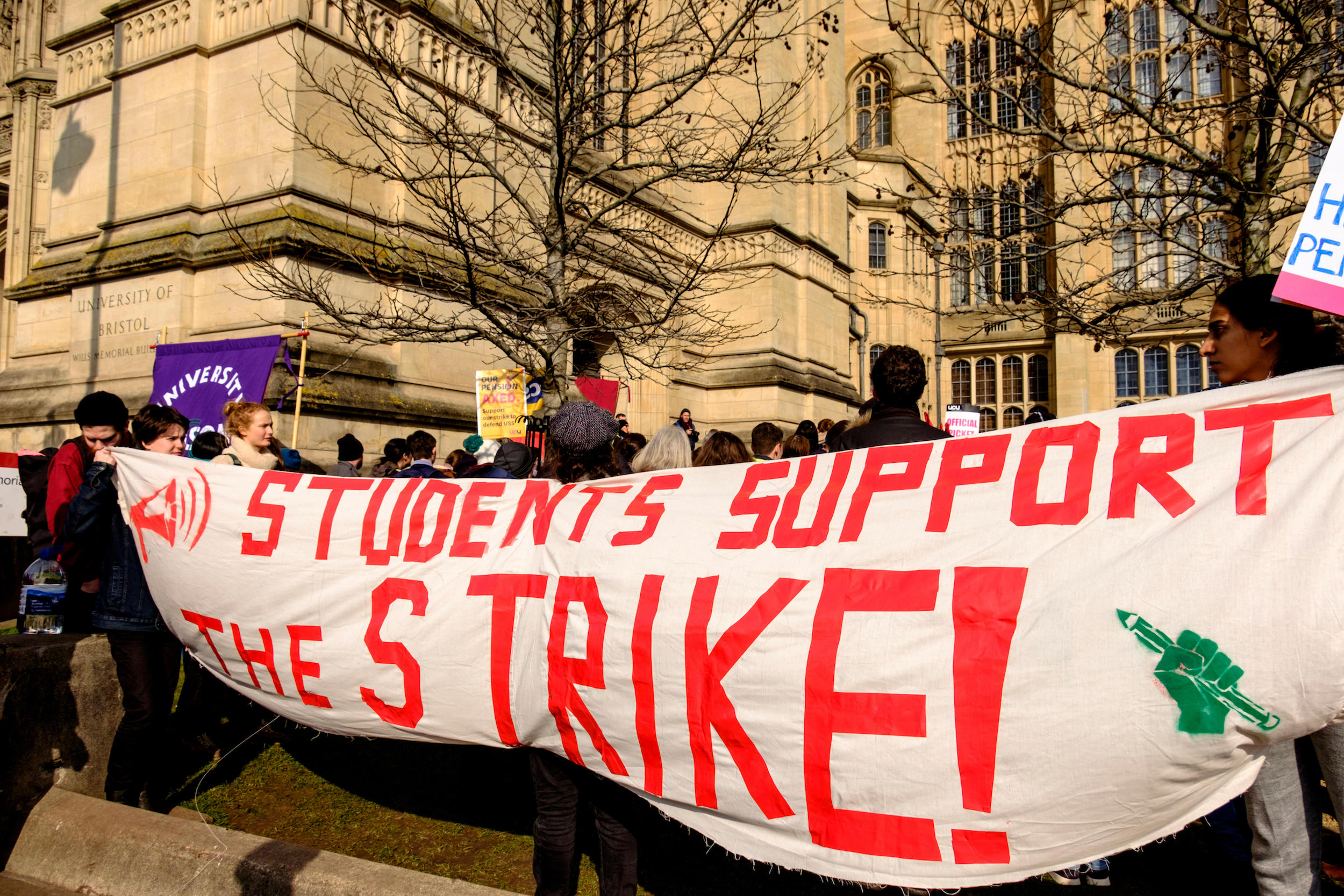

Last year, staff at 64 universities went on strike over proposed changes to pensions. A lot of early-career staff participated enthusiastically in these strikes, despite having no actual guarantee of receiving any sort of pension at all. At the time, there was plenty of talk about how casualisation would be the next issue addressed. But now, early-career staff are facing a struggle to have their problems taken seriously.

In the autumn, there was a ballot to strike over pay if UCU couldn’t negotiate more than the 2 percent raise on offer. The ballot failed to pass, as it didn’t meet the 50 percent quorum required by Britain’s draconian trade union laws. Currently, the action is being re-balloted: the vote ends on the 22nd of this month. Along with a higher pay rise, UCU is demanding national measures be put in place addressing casualisation and overwork, as well as closing the gender pay gap. It’s unclear if the current ballot will be met with any more success than the last one. So why won’t the better paid, more established lecturers help their beleaguered, casualised colleagues who went on strike to save their pensions?

“Most academics don’t have a problem with what they’re paid,” says Dr Jo Grady, Senior Lecturer in Employment Relations at the University of Sheffield. Despite the decline in real pay, “we’re pretty well-paid compared to the rest of the UK”. But that’s only true if you’re a lecturer on a permanent, secure contract, whose only future financial worry is having enough to retire on. Early-career academics do not have the luxury of complacency.

So what’s to be done? Grady, for her part, is optimistic that the ballot might pass this time. If members can be brought to understand that “this isn’t just about me wanting a pay increase, [but] about standing against the degradation of conditions”, says Grady, the ballot stands a real chance.

If permanent staff are too busy dreaming of their retirement cruise, perhaps early-career staff could work more closely with students instead. Students lose teaching hours because of strikes, but they’re also affected by the issues UCU is proposing to strike over. Some of the keener ones might later be co-opted into that academic outsider mass, but even if they’re not, spending their degrees being taught by overworked, inexperienced, insecure staff is hardly likely to mean they get the “best possible value” out of their degree.

“I think it’s a great source of shame for a lot of people that our sector extorts money out of students through fees, then delivers teaching by low-paid staff on insecure contracts,” says Grady. This is a sentiment echoed by Amelia Horgan, a PhD student at the University of Essex and postgraduate rep with the National Union of Students. “Disruption to scheduled teaching because of strike action pales in comparison to the threats that marketisation and casualisation pose to working – and learning – conditions.”

On this issue, then, the interests of students and early-career staff appear to coincide. Early-career staff need much better pay and conditions; students need staff who are better-paid and are not over-worked. Together, could the two constitute a new source of power at the heart of the university? As it stands, universities couldn’t function without student fees and early-career labour. Can students and lecturers break the mafia economics of the academic workplace?

This article originally appeared on VICE UK.