Man United are up for sale: What does it mean, and what happens next?

Gab Marcotti feels Cristiano Ronaldo leaving Manchester United with immediate effect will allow both the player and the club to move on. (1:22)

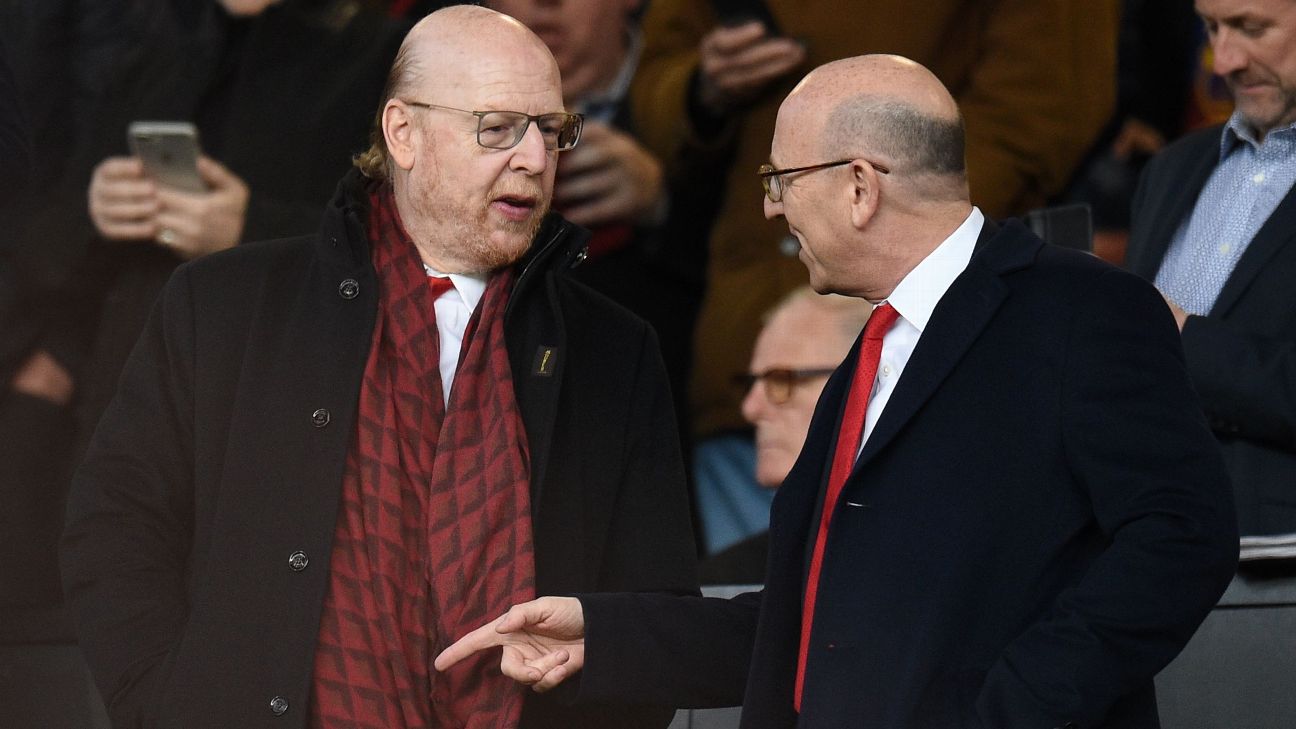

Manchester United are up for sale. The Glazer family, United’s owners since 2005, has announced it is exploring “strategic alternatives to enhance the club’s growth,” but strip away the carefully layered lines of the statement, and one word jumps straight out: sale.

– Stream on ESPN+: LaLiga, Bundesliga, more (U.S.)

Ever since angering United’s supporters by borrowing heavily against the club to fund its takeover 17 years ago, the American family, which also owns the Tampa Bay Buccaneers NFL franchise, has repeatedly stated that it is a long-term owner with no intention to sell. United were debt-free when the Glazers took ownership, but the latest financial statement revealed a net debt of £514.9 million.

But less than a month after Liverpool were made available by their American owners, Fenway Sports Group, for £4.4 billion, United are on the market and will likely be worth at least double. It means that the Premier League‘s two biggest and most historically successful clubs now have uncertain futures.

So what is the story behind the Glazers’ decision to invite offers for United, and what happens next?

There are many factors. There isn’t one particularly central reason, but the coming together of different strands that have all impacted the Glazers’ ability to run a club as big as United.

Primarily, this is about money. The Glazers need at least £200m to upgrade Old Trafford, which is the Premier League’s biggest stadium, but its facilities have fallen behind those at Manchester City, Tottenham Hotspur, Arsenal and Liverpool.

They also spent over £200m on new player signings this summer, despite commercial revenues slowing down due to a lack of success — the team’s last trophy was the 2017 Europa League — and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

United announced a net loss of £115.5m for last season, so the walls were closing in on the Glazers. They simply can’t rebuild Old Trafford, sign the best players and reduce their debt on their own. And with interest rates climbing sharply across the world, borrowing has become a much more expensive option. So the need to either attract a wealthy investor to help with all of the above, or simply sell, is clear.

The vocal and visible anti-Glazer campaign led by United’s supporters is another factor. While the Glazers have largely blanked out the protests throughout their time as owners, the fans’ groups believe their campaigns are making United a less attractive vehicle for potential sponsors — whose money the Glazers rely upon to drive the club’s revenue.

And another key element in the decision is the sale of Chelsea. All of a sudden, elite football clubs have a benchmark to measure their own value against, and the Glazers know that United could be worth up to four times the eventual Chelsea sale price of £2.5bn. Several high-worth individuals and private equity funds made the final shortlist to buy Chelsea, but missed out to a consortium led by Los Angeles Dodgers co-owner Todd Boehly.

All options are on the table. Sources have told ESPN that the Glazers place a huge premium on the kudos that come with owning this famous club, so the ideal scenario would be to attract an investor or partner to help shoulder the financial burden.

But as one financial expert involved in football ownership told ESPN, “those unicorns don’t exist.”

Mark Ogden lays out the options for Cristiano Ronaldo’s future after the forward left Manchester United with immediate effect.

Quite simply, if somebody has the money to invest in United, they are going to want their say in how it is run, and the Glazers can’t expect a bailout and the free rein to carry on regardless.

One key pointer toward the Glazers’ real motives is the enlisting of the American bank, Raine Group. Raine was hired by Roman Abramovich to find a buyer for Chelsea earlier this year. Raine addressed over 200 expressions of interest.

But from that process, Raine now has a list of hugely wealthy potential buyers for United on speed dial, and the Glazers know this. They will have seen the interest in Chelsea and realised that they could sell United quickly and make a massive profit.

Although the final cost of their takeover in 2005 was £790m, the Glazers invested only £270m of their own money — the other £520m was leveraged against United’s financial might — so a multi-billion-pound sale will see them walk away with a vast return on their initial outlay.

Much of the job for the new owners has already been done. Under Fenway Sports Group, Liverpool have achieved great success, including winning the Champions League and Premier League, with smart recruitment, astute financial decisions and ongoing investment off the pitch with a new training ground and a revamp of Anfield.

FSG has turned Liverpool into a successful machine having bought the club for £300m in 2010, and winning the Premier League in 2019 for the first time since 1990. Despite transforming the club’s fortunes, the challenge of keeping pace with state-owned clubs such as Manchester City (Abu Dhabi), Paris Saint-Germain (Qatar) and Newcastle United (Saudi Arabia) is becoming too difficult.

FSG now wants out before the upwards trajectory begins to flatline and potentially diminish the club’s value of around £4bn.

Under the Glazers, United have made the opposite journey to Liverpool under FSG. Where FSG inherited a mess, a club failing to recreate their glorious past, the Glazers bought a football and commercial juggernaut that was the world leader on and off the pitch.

Since the iconic Sir Alex Ferguson retired as manager in 2013, the success on the pitch has dried up, and the Glazers have displayed none of the smart, strategic decisions that have defined FSG’s ownership of Liverpool. In recent years, the Glazers have wasted colossal amounts of money on signings and wages in an effort to make United successful again, and they have reached the point where they can no longer chase their losses.

FSG is selling Liverpool having made them a success story, but at a time when it knows it will be tougher to keep that success going.

The Glazers, meanwhile, have run out of options, and any new owner of United would have to rebuild a crumbling empire.

United are one of the top three brands in world football, alongside Real Madrid and Barcelona. In terms of global fan base, history and commercial power, those three teams stand apart from the rest.

United are football’s version of the Dallas Cowboys or Los Angeles Lakers — all glamour and glory (or at least they used to be).

Speaking to ESPN earlier this month, Chris Mann, head of mergers and acquisitions for New York- and London-based global sports advisory group Sportsology, spoke of the “scarcity value” of elite football clubs for potential investors, so the prospect of owning United will generate huge interest and, in turn, drive up the club’s valuation.

Recent sales of two storied sports teams earlier this year offer a good guide to United’s value. Chelsea were sold for £2.5bn (Boehly’s group pledged a further £1.75bn in ongoing investment), while the Denver Broncos NFL franchise changed hands in a deal totalling £3.95bn.

Both Chelsea and the Broncos are big, well-known brands, but the Broncos aren’t the Dallas Cowboys and Chelsea aren’t Manchester United. It would be like comparing a Chevrolet to a Ferrari.

Sources have told ESPN that Liverpool are likely to attract a £4bn valuation, but United could go as high as £8bn. Why? Because of the ability of potential new owners to generate huge revenue streams on the back of United’s much greater global power.

Even though United have been a failing enterprise on the pitch for the past 10 years, they remain a Grade “A” sports brand, and sponsors continue to want to pay fortunes to be associated with them. United are the biggest house on the most prestigious road in town and, when they come available, somebody will pay whatever it takes to buy them.

The self-styled world’s biggest football club, the opportunity to make massive money on the back of it, the prospect of the glory that comes with winning Premier Leagues and Champions Leagues — and a rebuilding job on and off the pitch that could cost half a billion pounds.

However, if you have the funds to buy United, the cost of the tweaks that will be needed to bring everything up to scratch may not be too much of an issue.

The first job will be to restore Old Trafford to its previous position as the Premier League’s best stadium. The roof on the main stand leaks when it rains, a perfect metaphor for the state of the stadium after 17 years of Glazer neglect. It will cost at least £200m to upgrade the facilities and probably more if new owners have more ambitious plans than the Glazers, who have watched on as other clubs have improved their grounds or moved to new stadiums.

A new training ground, or modernised one, will also set any new owners back to the tune of millions.

And there will also be a hefty bill when it comes to making manager Erik ten Hag’s squad deep enough and good enough to compete for the titles that United once won with unerring regularity.

So while owning United will bring prestige to any new owner, it won’t be without initial problems and the need to spend plenty more than the acquisition fee.

The field of potential new owners in the Premier League has diminished quite starkly in recent months.

Russian oligarchs are out, due to the sanctions imposed by western governments as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, while the wave of Chinese investment into major European clubs has ground to a halt since the pandemic and limitations from its government.

Sovereign wealth funds, such as those behind Manchester City, Paris Saint-Germain and Newcastle, cannot own more than one club in the same competition (Premier League or Champions League), so that will impact the list.

But as the sale process for Chelsea showed, there is no shortage of wealthy individuals and groups in the United States, and that is the likeliest place from where the next United owners will emerge.

Britain’s richest man, Jim Ratcliffe, has already gone public with his interest in buying United, but he said earlier this season that the Glazers had made it clear they didn’t want to sell.

With a personal fortune in excess of £5bn, the boyhood United fan, who failed in a bid to buy Chelsea this year, is seen as the supporters’ choice. But Ratcliffe, who owns French team Nice, could be outbid by wealthier rivals.

Another major bidder for Chelsea was the Ricketts family, which owns the Chicago Cubs. It partnered with Ken Griffin, the majority shareholder in hedge fund group Citadel, whose personal wealth is reported to be in excess of £20bn.

Ares Managements, a Los Angeles-based investment company, has recently stated its ambition to add a European football club to its portfolio.

In 2021, 15 clubs in Europe’s big five leagues — England, Spain, Germany, France and Italy — were either taken over or invested in and two-thirds of those involved were American individuals or groups.

So while an incredibly wealthy individual or sovereign wealth fund could yet emerge as a buyer for United, potentially from India, Dubai or the oil-rich former Soviet republics of Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, the smart money is on United’s American owners being bought out by another American group.