Germany Mulls Postponing Nuclear Exit

Credit to Author: Sonal Patel| Date: Wed, 17 Aug 2022 22:24:32 +0000

Germany’s government is weighing how the closure of the country’s last three nuclear power plants in December 2022 will affect its grid this upcoming winter as the country scrambles to secure sufficient energy supplies amid a decline in Russian gas deliveries.

A formal decision on whether or not to keep Isar 2, Emsland, and Neckarwestheim 2—a combined 4.3 GW—operating beyond their currently scheduled phaseout date may not come for a few weeks. The government is currently conducting a second evaluation—a so-called “power grid stress test”—to determine whether the country’s three operational nuclear plants can contribute to keeping Germany’s energy supply sufficient throughout the winter. A spokesperson from the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action on Aug. 17 said a decision could come “in the wake of the results of the stress tests.”

The ministry was responding to an Aug. 16 report in The Wall Street Journal that said Germany plans to postpone the closure of the three plants. Citing three unnamed senior government officials but providing few other details, the newspaper reported that details related to the possible postponement are under discussion and that the decision will need to be formally adopted by Germany’s cabinet and likely require a vote in Parliament. However, an economy ministry spokesperson told Reuters on Aug. 16 that the report “lacks any factual basis.”

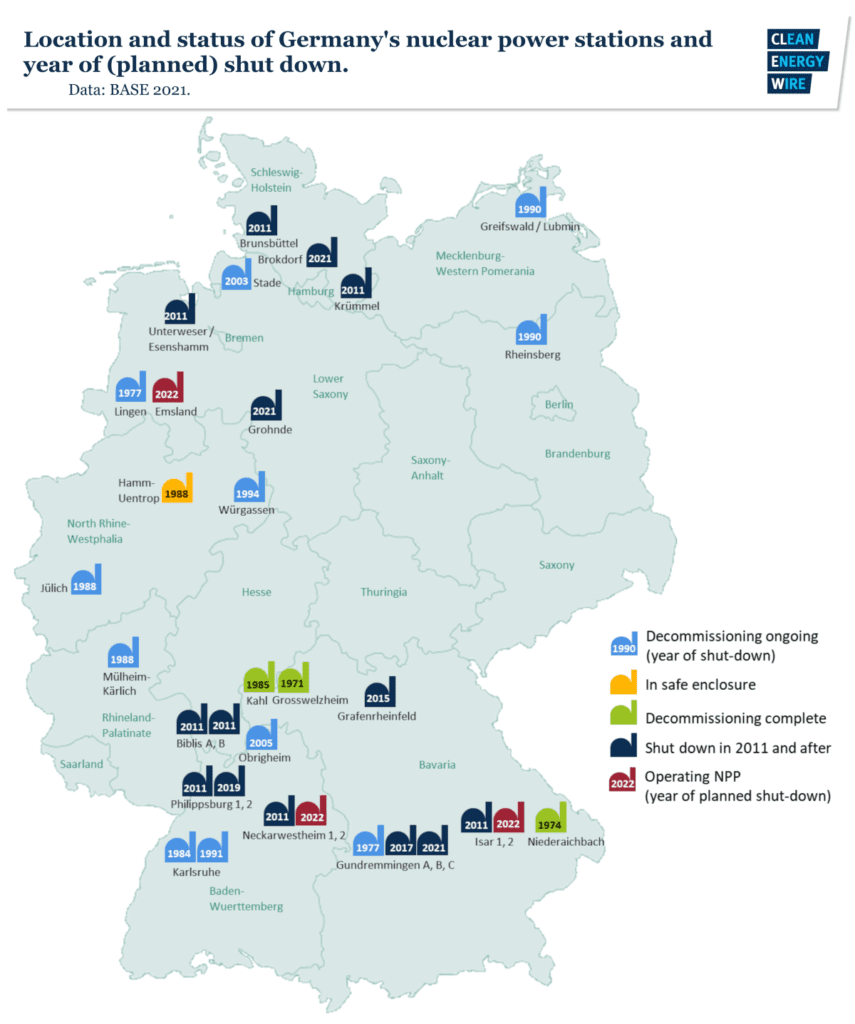

A formal decision to keep the plants running beyond their current closure dates would mark a divergence from Germany’s 2011-instituted accelerated nuclear exit in the wake of the Fukushima disaster. The country began shuttering its 9.5-GW nuclear fleet capacity at the end of 2021 with the closure of Brokdorf, Grohnde, and Gundremmingen C—a combined 4.2 GW—last December.

It also would mark a reversal by the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Nuclear Safety, and Consumer Protection and the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, which on March 7 in a joint evaluation concluded a lifetime extension of the three remaining nuclear power plants in the face of natural gas import bottlenecks from Russia is “not recommended, even in view of the current gas crisis.”

Quickly Intensifying Energy Crisis

When the government launched its first nuclear power evaluation in March, Russia was two weeks into its large-scale invasion of Ukraine. Germany’s government had jumped into action to protect its energy security after Moscow threatened to halt gas supplies via the Nord Stream 1 pipeline as retaliation for Germany’s decisive certification halt of the Nord Stream 2 Baltic Sea gas pipeline project. The $11-billion project completed in September 2021 had been expected to double the flow of Russian gas to Germany.

Germany’s energy security predicament, however, has grown even more intense since Russia on July 11 halted all flows on Nord Stream 1—the biggest single pipeline between Europe from Russia. Gazprom, a company with a monopoly on Russian gas pipeline exports, has blamed reduced flows on the delayed return of an industrial Siemens Energy gas turbine for the Portovaya Compressor Station (CS). Maintenance work on the turbine was recently completed in Canada, and it was shipped to Germany in mid-July. Gazprom, though, has refused to take delivery of and recommission the turbine owing to allegedly missing documentation. “Someone just has to say: ‘I want it’, and it’ll be there in short order,” said Federal Chancellor Olaf Scholz said during a news conference at the Siemens factory in Mülheim an der Ruhr on Aug. 3

The situation has left European leaders scrambling to address the prospect of a chronic gas shortage for this winter’s heating season, which begins in October. Fatih Birol, the head of the International Energy Agency (IEA), in July issued an impassioned plea that urged Europe’s leaders to minimize gas use in the power sector and temporarily ramp up coal- and oil-fired generation. These measures would guard against energy market turmoil that has grown “especially perilous,” Birol said. If Russia completely cuts off gas supplies before Europe can boost storage levels up to 90%, “the situation will be even more grave and challenging,” he noted.

Germany, which relies on Russia for 55% of its gas supplies, has for its part acted quickly. In June, it arranged for at least 8.5 GW of brown, hard coal-fired, and a small amount of oil-fired generation capacity—all due to be idled this year and next year—to be able to continue operating to provide electricity on demand. The measure is notable given Germany’s plans to exit coal power by 2030 or earlier. Under the coal exit law, an estimated 13.9 GW of lignite or hard coal-fired plants could be shuttered by the end of 2022.

Like several other European Union countries, Germany also committed to reducing its gas consumption by at least 15% (compared to average consumption over the last five years) starting in August. The country on Aug. 15 also said it will levy a temporary gas security surcharge starting in October to guard against potential bankruptcies by gas import companies. These companies must now “procure a replacement on the so-called spot market at much higher prices than agreed so that private households and the economy can continue to be supplied with sufficient gas,” the government said.

Germany Launches Second Nuclear Assessment to Weigh Electricity Sufficiency if Nuclear Plants Closed

Given Germany’s limited options, the prolonged operation of Germany’s nuclear power plants has grown more attractive. Bolstered by a stunning increase in public support as the nation braces for its winter gas crunch, the Economic Affairs and Climate Action Ministry on July 19 launched a second assessment—the so-called “power grid stress test”—to determine whether the country’s three operational nuclear plants can keep Germany’s energy supply sufficient throughout the winter.

The ministry, led by Green Party minister Robert Habeck, has suggested the second assessment, which power grid operators requested, will “clarify” whether Germany will have sufficient electricity production capacity when the nuclear plants go offline on Dec. 31 as planned. “We will now calculate again and then make a decision on the basis of clear facts,” a ministry spokesperson told Reuters. However, it is still unclear to what extent the second assessment’s results, which are expected within “a few weeks,” will inform the government’s decision.

Any decisions to keep the nuclear plants open, however, are certain to face political scrutiny. Within Germany’s three-party coalition government, Habeck’s Greens party and Chancellor Scholz’s Social Democrats party have so far pushed against continuing nuclear power generation. Some party members in Munich, however, have called for the extension of some of the plants under certain conditions. The pro-business Free Democrats have meanwhile proposed a change of strategy if necessary that could keep the reactors in operation for a limited period of time.

First Federal Assessment Listed Several Hurdles to Keep Existing Plants Open

Still, how Germany will overcome the litany of issues barring the continued operation of its nuclear reactors remains unclear.

The economy and environment ministries’ joint evaluation in March (translated here in English by Tomas Pueyo from Unchartered Territories) notably outlines several substantial legal and regulatory hurdles. Prominently, the reactors cannot be operated beyond December 2022 under Germany’s Atomic Energy Act, and prolonging their operation will require an amendment to the law, the evaluation claims. The government also claimed that a statutory extension could require a cross-border environmental impact assessment (EIA) that must abide by a European Court of Justice judgment, as well as a new, comprehensive risk and benefit assessment by Germany’s legislature that would balance assessments after the Fukushima accident in 2011.

On the regulatory front, the reactors would need to address safety and security requirements. Because the reactors are slated for shutdown by December 2022, a legal exception under the Atomic Energy Act allowed them to bypass their 10-year safety review, which should have occurred in 2019. “The last extensive safety review took place in 2009,” the assessment notes. “If operation continued after January 1, 2023, the last safety check would be 13 years old and a new one would be mandatory.”

Continued operation “would only make sense” if the safety review were “significantly reduced in scope and test depth and/or extensive retrofitting measures that might be ordered in the course of the safety check were dispensed with,” the assessment adds. Under that scenario, legislature would accept an “accelerated and streamlined safety review,” including a waiver of any retrofitting. However, that would make a “break with the previous German safety philosophy in the operation of nuclear power plants,” it notes.

Technical Concerns: Adequate Fuel, Spare Parts

Then there are several prominent technical challenges. One is that fuel elements in the plants “have been largely used up.” The reactors may have enough fuel for about 80 days of extended operation if they are shut down in the summer of 2022 or operated at lower power. Procuring new fuel for the reactors is a lengthy process, which could take between 18 and 24 months, and in an “accelerated” case, 12 to 15 months, the assessment notes.

“In addition, a significantly larger quantity of fresh fuel elements (estimated to be around a factor of 2) would have to be manufactured during this time than in the previous annual cycle,” it adds. “This also requires a considerable amount of testing, i.e. extensive calculations, assessments, and official approvals are necessary in order to determine and prove the safety of all operating parameters of this core composition. Even with an immediate order and accelerated processing, use is therefore not to be expected before autumn 2023.” Other technical issues noted in the report include an uncertain stock of spare parts, which could face delays owing to supply chain disruptions.

Another possible hurdle involves ensuring staff at the plants will be available to run the reactors. “The human resources required for timely continued operation are no longer available and would first have to be built up again,” the assessment says. Owing to the phaseout, reactor owners and operators had reached contracts with staff. Replacing them with new staff would require replacing and training a workforce in the “high double-digit” number.

The prolonged operation could ultimately also prove financially hefty, the assessment concludes. Nuclear plant operators have signaled that they may only assume the necessary financial investments if they make sense economically—which would likely mean operating the plants for at least another three to five years. If forced to keep the plants open, the federal government should assume a “quasi-owner” role—with “full control and responsibility for investments, costs, yields and the scope of the depth on the safety and licensing side,” the assessment says. “In such a scenario, the nuclear power plants would be operated by the companies on a quasi-government basis.”

Nuclear Trade Group: Prolonged Operation Achievable, With Benefits

The government’s first assessment, however, has drawn criticism. In a detailed response, Germany’s nuclear business and technology association KernD pointed to several “misconceptions” that it said moot the government’s conclusion. “Quite the opposite, the nuclear power plants with their ability to generate the power for the baseload could provide a crucial contribution to energy security in a situation where there is a shortage of gas or even a general energy economics emergency in Germany, without incurring disproportionate expenditure,” it said.

“The facilities, the staff, the know-how, the supply chains—in short, the complete technical and economic nuclear system—are all still available after all, unlike [liquefied natural gas] terminals, additional power and gas lines, many additional renewable energy generation facilities or provider contracts for very large quantities of liquid gas from the highly competitive global market. And not least, the nuclear power plants would provide low-emission power in continued operation, which would stabilize the trend on the electricity market with low and stable generation costs,” KernD added.

The group argued that by restoring the reactors’ original licensing status, Germany’s three reactors could continue operations and wouldn’t require safety analyses until 2028 or 2029. The plants in 2014 already upgraded technical safety attributes following robustness analyses and stress tests required after the Fukushima accident, the group noted. “In the view of KernD, the nuclear power plants can continue to operate at the existing safety level without any tradeoffs,” it said.

Plants already shuttered may also be reopened, the group argued. As long as the plants have not formally received approval for demolition, their existing operating licenses still apply under the Atomic Energy Act, it claimed. “From the point of view of administrative law, the licenses are actually still valid, since the Act does not suspend them,” it said.

KernD also said the government’s interpretation of the European Court of Justice’s (ECJ) ruling requiring a cross-border EIA is flawed. “The ECJ had to rule firstly on an extension of the operating period by 10 years—which is currently not the issue here—and secondly prescribed an important exception for the case that the member state proves that energy security would otherwise be threatened. Precisely such a threat is now the reason why analyses regarding the continued operation of nuclear power plants are currently being carried out at all,” it said.

The government’s cited technical limitations concerning fuel availability are also “not correct,” the group said. Isar 2, specifically, can generate additional power for several months in spring 2023 with its existing fuel in a “stretch-out” operation—which means utilizing its fuel beyond the planned end of the cycle. Also of note is that the nuclear industry in Europe “feels obliged to support the electricity supply in Europe.” If the sector immediately prioritizes procurement of fuel assemblies to extend the operation of Germany’s plants, the reactors could have enough “in good time for a short cycle in winter 2022/2023,” allowing for larger refueling quantities to be procured later in summer 2023, the group suggested.

In addition, the government’s staff resource concerns could be easily remedied, the group contended. “For short-term or medium-term continued operation, the operators are able to cover the staff resources in principle. In addition, staff from other sites could be retrained within one year,” it said.

KernD underscored that any effective contribution made by nuclear energy to prevent a critical energy crisis would require “fast, political strategic decisions.” The government should also look beyond the short term, it suggested.

“The length of time nuclear power can make a useful additional contribution depends on the general geopolitical and energy-economics situation,” it said. “The possibility of continued operation in the medium term instead of only the short term is certainly not a disadvantage or even an obstacle, since the European Commission recently announced it was aiming not to be dependent on Russia for fossil fuels by 2027 by means of its REPowerEU initiative, for example.”

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine).

The post Germany Mulls Postponing Nuclear Exit appeared first on POWER Magazine.