‘Weapon Detecting AI’ is Now Scanning Students in South Carolina Schools

Credit to Author: Todd Feathers| Date: Tue, 25 Feb 2020 16:00:41 +0000

Over the past year, administrators at West Florence High School have deployed a variety of new surveillance technologies, embracing a distinct vision of the future of public education.

Earlier this year, the South Carolina district installed vape detectors—which come equipped with chemical sensors and microphones that send alerts directly to the principal—in bathrooms and hallways. During their first week of use, the devices caught 12 students. School-issued Chromebook laptops also now come pre-installed with Gaggle, a new breed of surveillance software that monitors students’ every action on the devices, both on and off school grounds.

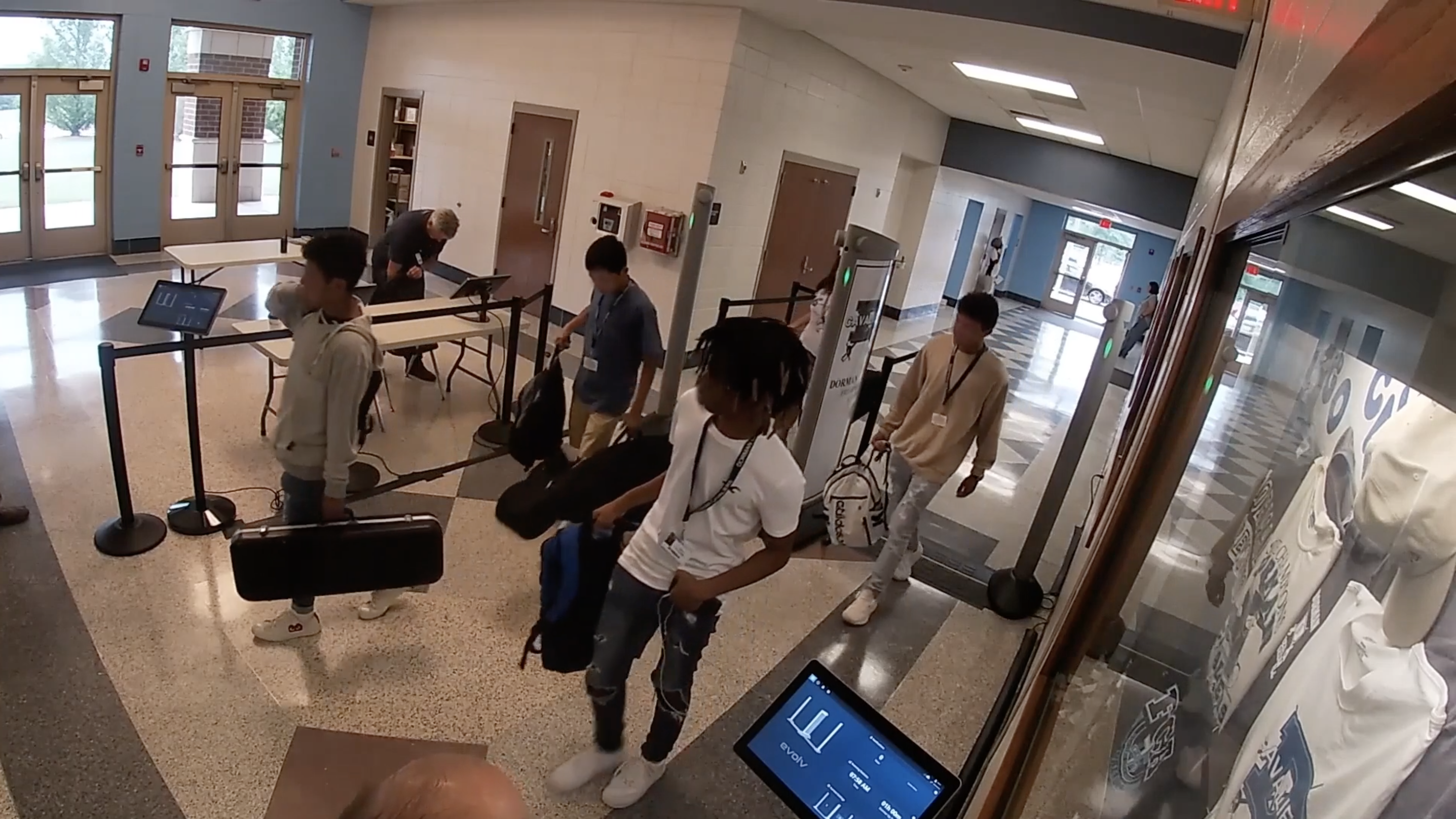

And most recently, the metal detectors that stood sentinel at school entrances have disappeared. In their place, schools across Florence District 1 are now equipped with millimeter wave body scanners from Evolv Technology. The company claims that the devices, which are similar to modern airport scanners, can scan 60 people a minute using machine learning algorithms that detect guns, knives, and other threats, and then notify security guards exactly where the objects are on a person’s body.

WFHS student body president Ella Kitchens told Motherboard that she and her peers are well aware of the new surveillance system. They aren’t agitating against it, but they aren’t entirely convinced it’s making them safer, either.

“I personally like [the new weapons detection system] and a lot of my friends like it just because it’s a lot quicker and more efficient than metal detectors because we can keep our backpacks on,” she said. “I don’t really think the metal detectors, in general, or this is helping that much with safety.”

“That’s the thing about this new system, is they monitor everything,” Kitchens added. “They definitely have a lot of other different technology devices implemented to make it feel like they’re watching us.”

Florence District 1 and Spartanburg District 6, which are both in South Carolina, are the first two districts in the country to install Evolv’s body scanners, according to the company. They are the latest example of how the epidemic of school shootings has ignited the high-tech school security industry, fueled by federal and state governments pouring money into safety grants.

Educators in places like Florence are understandably predisposed to spend that money and err on the side of caution. But student privacy and civil rights advocates worry that some districts are being hoodwinked by for-profit companies that promise more than their technology can deliver in order to capitalize on the fear of mass shootings.

During the previous two school years, there were five incidents involving someone on or near Florence District 1’s campuses possessing guns or explosives, according to state data. There was one incident in Spartanburg. None of them resulted in violence or involved any threats being made.

In February 2018, WFHS went into lockdown after administrators found a loaded magazine in a student’s backpack. The next month, police arrested another West Florence student after a security guard found a loaded pistol in his truck. And in August 2019, two students were expelled after threatening a shooting at WFHS, while a third was expelled for threatening to bomb nearby South Florence High School.

District administrators from Florence and Spartanburg declined to comment for this story.

During an October meeting, Florence Superintendent Rich O’Malley told the school board that Evolv’s scanners would cost $364,000 for a four-year lease. There was also a discount in place if the board voted to approve the contract that night, he said, according to minutes of the meeting.

O’Malley explained that the body scanners would cut down on the amount of staff time required to operate the metal detectors. During that meeting, he did not address how the scanners would keep students safer, or whether there was any evidence that they were more effective than metal detectors, which have produced mixed results themselves, according to the minutes.

In a brief interview, Florence school board member John Galloway told Motherboard that he wasn’t aware of any evidence presented to the board regarding the Evolv body scanners’ accuracy. He did believe the district sent a security guard to a nearby school—likely in Spartanburg—to observe them in action.

“I think it is really, really important with this technology in particular to deeply investigate and seek out the external research and external proof that this technology works,” Amelia Vance, director of youth and education privacy for the Future of Privacy Forum, told Motherboard. “One of the things we’ve seen again and again post-Parkland is school administrators being flooded with proposals for expensive technology that have no evidence base behind them.”

“Is it really worth the discrepancy in cost?” Vance added. “Any time you’re spending money on something you’re taking money away from more school counselors. If we’re spending a ton of money on this new technology, which could improve the surveillance effect versus a metal detector, but we’re not able to bring in any more counselors, then any advantageous effect would be mitigated.”

Evolv did not make any of its executives available for an interview prior to this article’s publication. On its website, the company says its technology has scanned more than 50 million people in venues like stadiums and airports and detected 5,000 weapons. The company isn't the only one selling weapons-detection systems to schools, but it does claim to be the only one whose millimeter wave sensors and proprietary machine learning algorithms allow its devices to scan multiple people at once, in a free-flowing stream.

Evolv does not publicly provide any research on how accurately the Evolv Express scanners detect weapons, or how many false positives they turn up—an area of particular concern to civil rights advocates, who note that minority students are more likely to be pulled aside and searched and that discipline in schools falls disproportionately on the shoulders of black students, contributing to the school-to-prison pipeline.

Even amid universal fear that a mass shooting could happen at any school, the evidence shows that the weight of increased surveillance falls heavier on minority students. In a novel study drawing on a restricted national database of school security measures and incidents, University of Florida law professor Jason P. Nance found that, in the wake of the Sandy Hook School shooting, schools were more likely to adopt stricter security measures if they had higher proportions of non-white students, even when controlling for other factors like poverty rates, instances of violence in the school, and local crime rates.

Spartanburg District 6 schools are 60 percent minority. Florence District 1 schools are 65% non-white. The average in South Carolina districts is 50 percent, according to state data.

“We have this system where the millimeter wave system claims there’s a knife in a student’s jacket and whether or not an officer actually chooses to frisk them comes down to that student’s class or race,” Albert Fox Cahn, executive director of the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project, told Motherboard. “I don’t think the solution to school safety is to transform our classrooms into an authoritarian surveillance state. I’m just thinking of how chilling this will have to be for students who have to walk through, especially those who fear the system will reveal the contours of their body and electronically undress them.”

This article originally appeared on VICE US.