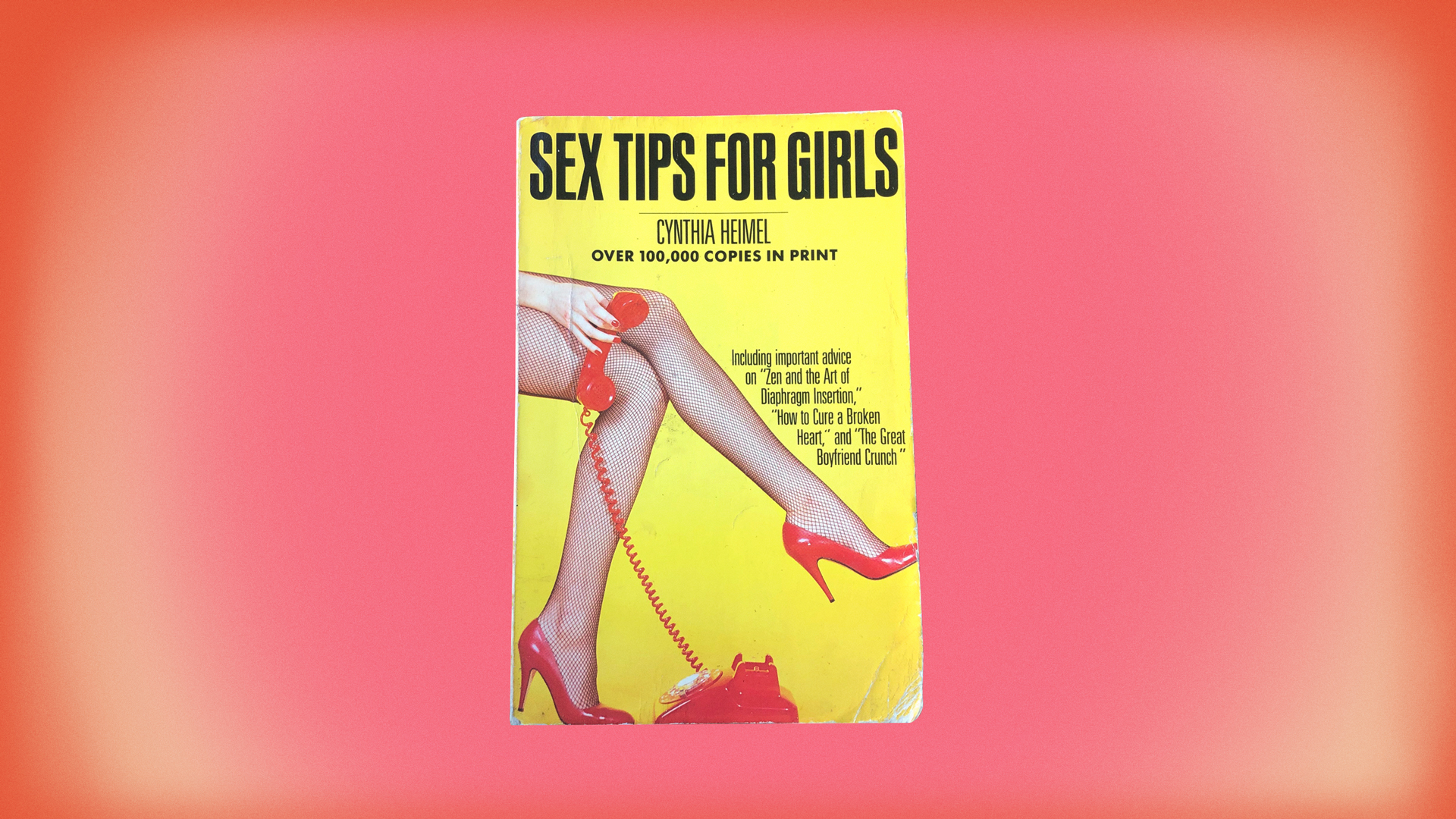

Love/Hate Reads: ‘Sex Tips for Girls,’ Revisited

Credit to Author: Maggie Lange| Date: Fri, 14 Feb 2020 21:07:58 +0000

There’s no sex in the title of Cynthia Heimel's 1983 book, Sex Tips for Girls, meaning there’s no: sensation, allure, lust, tension, forestalling, distance and collapse, gasping, joking, or slyness, for example. This title is nothing but business. This is Heimel’s first joke: Party seems like a fair way to categorize the genre and form of her literary debut. She weaves exaggerated memoir with thoughtful advice, all stylized as jokes and hardball flirting with her audience.

Published when Heimel was 36 and pushed into the book world as collected wisdom dressed in a funny bright coat, Sex Tips for Girls is a feat of crystallizing uncontainable energy. Reading Sex Tips for Girls prompted me to subconsciously wander to my laptop and search for “bright green snakeskin boots” online. There is no mention of bright green snakeskin boots in Sex Tips for Girls, but the book summons the most intense, frivolous life force in the soul, a feeling that makes you want inappropriate, bright new shit-kickers.

The book does relay actionable tips about sex and confidence and shoe color (red, actually), but the active function of these tips is to impart an ethos that tells you how to live your whole life Heimel’s philosophy is: sharp irreverence, independent permissiveness, blissed-out humanism.

I hunted down a used copy of Sex Tips for Girls after I read an obituary for Cynthia Heimel two years ago. I learned that she was a sentimental renegade in a leather jacket, a brutally funny critic of sexual encounters, and a dog person. She was born in 1947 in Philadelphia and wrote columns for the Village Voice, and Vogue and Playboy, where she was the first woman columnist to write about women. Her writing is intoxicating and flummoxing, from a mind that can’t stand still between satire and earnest affection.

Sex Tips for Girls is also a landscape portrait of 1980s downtown New York, a document of nocturnal propulsion, New Wave, glamorpusses, attainment, Quaaludes, champagne, the bean sprout diet. There are at least two mentions of emerald brooches, and I am entirely unable to determine whether they’re a joke about consumerist excess or a desirable accessory. From these trenches, the book is a field report about the thawing Cold War between men and women. As Heimel puts it after 1970s radical feminism declared dudes the enemy: “Some men are OK now. We’re allowed to like them again. We still have to keep them in line, of course, but we no longer have to shoot them on sight.” It’s a time of unconflicted abundance. She holds no tolerance for one-trick phonies and she carries a soft spot for rogue musicians. Her world is filled with hot dates, so there’s no energy for anyone she’s not wild about.

Sex Tips for Girls is dizzy with options. “These are times that try a girl’s soul… Should we take vitamins? Wear dresses? Shave our legs? Demonstrate against nuclear power? Dance until dawn? Eat natural foods?” It’s a proto-moment of ultra-choice feminism. This paralyzing, and ultimately entrapping, imperative insists that women can now pursue their truth, whatever it is—and, in fact, as long as they can do so ethically, they must pursue it. The only unacceptable position is to waver. Heimel’s work is like a navigational tool developed by an enthusiastic research scientist. She proposes that if you’re lucky enough to be at sea with options, you have to get very close with your own sense of desire.

Sex Tips for Girls has aged with some stains, like many a juicy primary text. Any reader with their own intersectional ringer will cringe. As a contemporary person, I got very growly at Chapter 11: Inner Dieting, which assumes thin-trim-slim is a prerequisite for people who want to date and continues with a deeply misguided taxonomy of types of fat women. But even there I found some nuances (“she gets laid as often as any of us”) alongside the blunders. With some willful effort, I even glimpsed queer fluidity. There’s a fascinating advice column submission from a straight woman about a gay man who she thinks is hinting he wants to fuck her. Heimel’s answer explains that attraction comes in many forms, and this probably isn’t sexual, but, why not see if it is? And if it is, go for it!

Heimel never feels innocent, and she has points: “Give sex the respect it deserves… Sex is important! Sex is profound! Sex is funny!” I can tell by her staccato that Heimel had to fight for this claim, but now (blessedly!) this insistence is unnecessary. I would love to tell her that she won her case: We do think sex is important! Funny! And though many aspects of sexual relations have become thornier, I’m glad that sex’s importance wasn’t a battle I had to wage, first privately, then publicly, with the world.

Sex Tips for Girls is literal and not. There are sex tips. The swirling tongue, etc. These sections are lackluster, even though Heimel is always funny. But then there are some new-old insights. The afternoon—what a terrible wasteland for running errands. “Instead, why not fuck? It is extremely sluttish, wicked, and slothful to fuck in the afternoons, and therefore totally enjoyable.” She includes an amazing off-the-rails diet which entails acquiring (1) lingerie, (2) vitamins, (3) vegetables, (4) good new records, (5) 20 Quaaludes, (6) two grams of cocaine, and (7) someone fun to have sex with, so you can dance and fuck all night and day for two weeks. Heimel claims she doesn’t condone it, says she simply found the diet on a note that flitted out of a library book. She trusts the reader to assess the strategy for themselves.

Halfway through her book, she gets to a chapter called “Sex and the Single Parent.” I, horribly, read this as: Twist! Heimel’s been romping around New York, living a scintillating life and has also been a parent this whole time! The book says, yes, why wouldn’t she be? She has other things to worry about: “What if your fellow buys your kid a drum kit? And what if they hate each other? And how dare you go out on dates anyway? What kind of a mother are you? A rotten one? Should you be constantly at home, nurturing?” This chapter slapped me right in my own blind spot.

Heimel is daring, critical, benevolent, and incisive about the cultural hothouse she’s in. This attitude comes across as a way to approach sex and life. You can be unsure and interested and curious, you can get yourself into an experience only because you want to have it. Heimel’s attracted to experience itself, she’s horny for sensation, she lusts after the world. At one point, she provides a seduction technique to “exude a cool but promising skepticism,” and I thought: Oh, that’s a whole worldview, contained just right there.

Follow Maggie Lange on Twitter.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.