‘Kentucky Route Zero’ Creators on Finding Hope and the Burden of 4K Gaming

Credit to Author: Lewis Gordon| Date: Fri, 14 Feb 2020 13:59:57 +0000

There are spoilers for Kentucky Route Zero Acts I-V below.

Kentucky Route Zero — the five act point and click adventure by Cardboard Computer — confronts loss at every stage of its thoughtful journey. Conway, a man who delivers antiques for a living, is about to be retired. Lysette, his boss and friend, suffers from an ailing memory. A young boy, Ezra, no longer has a family or home while the workers in Elkhorn Mine arguably encounter the sensation most sharply — their own lives are cut short because bosses told them to dig too deep. Such heartbreak plays out almost exclusively in strange, negative spaces defined by absence as much as anything else. I won’t spoil what happens at the end of its final episode — released just a couple weeks ago — but, needless to say, the lives of these characters do not suddenly fill back up.

Set in Kentucky mostly at night and mostly underground, its creators describe the game as magical realist but it is both more unsettling and mundane than the genre’s literary touchstone, Gabriel García Márquez’s 1967 novel One Hundred Years of Solitude. Ghosts, memories, and money haunt almost every scene like the eeriness cultural theorist Mark Fisher described as a “failure of absence or a failure of presence .” As Conway, Ezra, and the other drifters venture deeper into the game’s cavernous spaces, they seem to discover Fisher’s “underside of contemporary capital’s mundane gloss.” Homes and workplaces lie abandoned, people forgotten, and a noose-like debt ensnares almost anyone who comes into contact with the game’s most antagonist-like force, the Consolidated Power Company.

In his review for Vice, Austin Walker examined how the game explores this pervasive capitalism, from the shame it instills in those who fall outside its narrow metric of success to the way the system mediates death. Occupy a space down the pecking order, as Kentucky Route Zero’s characters do, and you’ll slide closer to the grave, lacking access to basic amenities such as clean drinking water, medical care, and safe transit. “Whose homes can survive a disaster?” wrote Walker. “And whose fault is it when these things go wrong?”

Kentucky Route Zero is the culmination of nearly a decade’s work for writer Jake Elliott, artist Tamas Kemenczy, and composer Ben Babbitt, all alumni of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. As the years have worn on, the three person team has stretched, contracted, and reshaped the possibilities of its fundamental tools: text, art, and music. The game might share a mechanical resemblance to other text adventures — including the genre’s progenitor Colossal Cave Adventure (which Elliott played as a kid) — but it’s moodier and more serious-minded than anything I’ve played. Despite following what Kemenczy describes as a “dream logic,” the game feels more resonant with social realist filmmaker Ken Loach whose I, Daniel Blake explores similar systemic injustices through a personal lens. Like the British director’s work, Kentucky Route Zero is rooted in long conversations and everyday details, seething with quiet fury about the ongoing abuse of power.

This interview, which took place over a video call with all three Cardboard Computer members, has been edited for brevity and clarity.

VICE: It’s been almost seven years since Act I came out. Obviously a lot has changed over this period, which I’d like to get into, but what changes occured in your own lives?

Jake Elliott: Ben and I both moved out of Chicago during that time. I'm living in Elizabethtown, Kentucky, and Ben's in Los Angeles. I've got two kids.

That's a big one.

Elliott: Yeah, right.

Ben Babbitt: Seven years of life for three people. A lot happened for sure.

How have your feelings towards the project changed over the last seven years?

Tamas Kemenczy: I'm still into the subject matter. I'm less compelled by the rigidity of the art style which we established. I was very stubborn about sticking to it.

Elliott: The story and the work itself have remained compelling. We've done a lot of formal experimentation over the course of the game. Even though it's still this point and click, multiple choice dialogue structure, we've found ways to experiment and keep the work growing. For my part, writing the dialogue, in each episode or interlude there's a moment or scene which undermines the formal vocabulary we had already. In Act IV, we added one scene where there's two conversations happening at once that affect each other. In Act V, the cat's dreams about the town, or however you want to look at those little vignettes, have the hypertext treatment.

When the game first emerged in 2013, it felt like a really timely exploration of how economic forces impact people and their communities. Then, when the prospect of a Trump victory was looming a few years later, the game felt like it resonated with the deluge of parachute journalism into what writers referred to as “ Trump country .” What are your memories of the first few years of the 2010s?

Elliott: Certainly we were living through the consequences of the financial stuff that happened in 2008 and 2009. It felt like that was really pervasive and really everybody was dealing with the consequences of that. What's happening now also largely feels like a consequence of that. Kentucky, Appalachia, and this part of the country — when Trump was elected there were a lot of people in the country eager to scapegoat the working class of the south and Appalachia specifically as being responsible which is ridiculous. It was always a skewed, weird way to rationalise what happened with that election.

There was the book, Hillbilly Elegy, that was sort of about how the Trump moment was a consequence of the moral failure of the people living here. That was a pretty big thing. For us, in the late part of the game, around when we were working on Act V, this other book came out, What You're Getting Wrong About Appalachia by Elizabeth Catte. She's a public historian and it’s a rebuttal to Hillbilly Elegy and that way of historicizing this area. So there was this moment where Kentucky and Appalachia were in the media, in this bizarre twisted way, for the wrong reasons, and then a lot of people from this area were writing their own history and countering that. There was a lot of really inspiring work coming out of the last few years, writing about the radical history.

What about you, Ben?

Babbitt: I was in college so that first part of the decade was turning 21 and being in school in Chicago. Youth, really. Not having any idea what the fuck is going on or how to do the things I was trying to do. One of the biggest things that happened for me was meeting Jake and Tamas and starting to work on this project. It was also the first time I was old enough to vote in a presidential election. Obama was first term so it was the optimism of youth combined with this cultural optimism, which I had never experienced.

Kemenczy: I remember his acceptance speech. He was in Chicago in Grant Park.

Babbitt: Yeah, I was there.

Kemenczy: I remember when it ended — the streets had no cars in them, and from facade to facade, it was just filled with people — this mass exodus leaving Grant Park. It really did feel like this cultural moment.

How would you characterize the present?

Babbitt: It's a different world. That's not to say there wasn't a precedent for what's happening now during the Obama era, but it feels pretty different to live in this country in 2020 than it did in 2008.

Jake, your partner is from Kentucky and you moved there in 2014, right? Can you talk to me a little about your experience of the state and how it’s changed in the following years.

Elliott: I think my perspective has certainly changed. I've learned a lot about the historical forces that have set things up the way they are. I live near Elizabethtown. I'm not in the city limits so I can't actually vote on city matters but that's where my office is. I've found that Elizabethtown — it's thirty to forty thousand so a small city — has a pretty suburban feel. The politicians are all pretty conservative and I've gotten a better understanding for what is the suburban conservative more than the rural conservative. We have a lot of work to do in the suburbs. It's pretty frustrating how intransigent some local politicians are but there's some really great politicians in Kentucky, too, especially at the state politics level.

How have you familiarized yourself with local politics? Have you become involved in any community initiatives?

Elliott: A little bit. I've gone and participated in protests and mostly familiarized myself just from following it more closely. Hardin County is the name of the county I live in. There's a group called Heartland Progressive Alliance I follow and watch for different opportunities to be involved in protests. But it's a small city so when I have gone to a protest here, I get to see which of my neighbors is on which side, which is sometimes a little distressing.

Is it ever surprising?

Elliott: Sure. When I lived in Chicago it was a little bit more of a given that people that I was working with or working alongside at different spaces were gonna be politically progressive or at least liberal. And here, it's not so much of a given we agree on stuff, even if we get along professionally.

When I read Hillbilly Elegy , it seemed like this strangely flattened version of reality. On the one hand, it’s an often vivid personal account but on the other, Appalachia appears as this almost entirely white monoculture. There’s a wonderful image in Act V which feels almost diametrically opposed to such a depiction. Did the popularity of Hillbilly Elegy and related media impact how you wanted to depict communities in Kentucky Route Zero ?

Elliott: Yeah. There's Catte's work and the podcast, Trillbilly Worker's Party. The three people who do that podcast live in eastern Kentucky in Letcher county and they're activists. They've done some really great direct work like blocking a prison from being constructed in the area. I was thinking about portraying not just the racism and exploitation by industry and the state but the real history of radical work and people caring for one another when the corporations or the state would exploit them and take their resources away, more or less leaving them to deal with the fallout. By being put in that position so many times, I think the people of the area developed a lot of tools for caring for each other through those difficulties.

Mary “Mother” Jones, the co-founder of the Industrial Workers of the World, has this harrowing quote: “The story of coal is always the same. It is a dark story. For a second’s more sunlight, men must fight like tigers. For the privilege of seeing the color of their children's eyes by the light of the sun, fathers must fight as beasts of the jungle.” Coal is still a huge industry in Kentucky and plays a big part in the game. How did you find conducting the research?

Elliott: You can even look in the news today. There's coal miners blocking a train trying to leave without paying them. That stuff is really recent history. These companies have all these half measures, like state-mandated pension programmes that are abandoned without any consequence when the company gets restructured. The total abdication after all of these claims to ownership of the land and people is still going on. It's disturbingly close at hand given how far this history goes back.

Tamas, how did the visual research impact you?

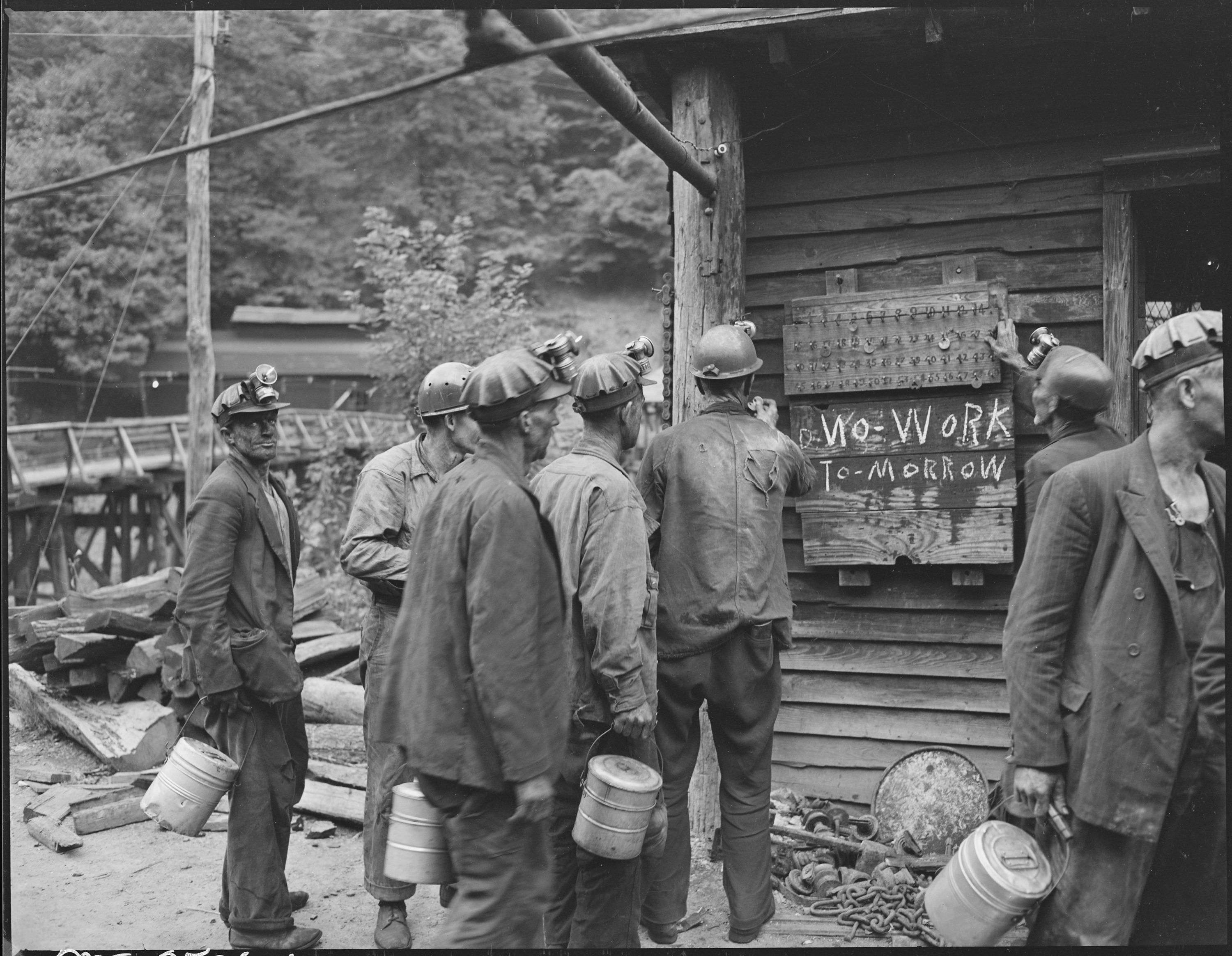

Kemenczy: It was haunting learning about the particulars of the living situations in these company towns. I'm looking at photographs but I'm reconstructing it as a video game, especially in Act I with Elkhorn Mine. I sort of exist in these digital spaces for a while. Parts of it were very technical — looking at exactly how coal mining happened in the ‘20s and ‘30s, reconstructing the gear, the safety conditions which were precarious, how they built stilts to stop the ceiling from collapsing. There’s this memorial in Act IV which workers tried to create. I was thinking about what these people would have as resources to build a memorial. They're down there building these tracks, so all they would have is the detritus around them and the helmets they were able to scavenge.

One photograph is really striking to me. There's a board where they clock in and out and there's a chalkboard next to it which says, "No work tomorrow." They're in these remote towns and it's really hard to get in and out and their currency is provided by the company, and you can only buy from this company store. And then, in the ‘20s and ‘30s, there's the Great Depression, so these people are isolated. They need to work to get the scrip but there's not enough around.

The characters look almost skeletal.

Kemenczy: A lot of the characters are emaciated in the game. It adds to that emotional quality, the sort of internal mental health extrapolated into a physical health.

The final act takes the game into sunlight. Can you talk to me about creating that environment?

Kemenczy: I've passed through Kentucky, West Virginia, and North Carolina — some of these hollows — and tried to capture how isolated those spaces can be. As for the daylight, that was a sheer desire from having spent years in darkness and a subterranean context. I'm one of those people who gets Seasonal Affective Disorder. I spent a lot of time with the environment. It's not next gen but it felt next gen for us, incorporating the shadows to indicate the passage of time. Even very simple things like during the mid-day, there's clouds and the light dims a little and then dims back up. That feeling, those little details, were important to get right.

I thought I was imagining the light shifting.

Kemenczy: Yeah, it's such a small programmatic operation but I was really happy with the emotional effect it drew.

In Act V , there’s this mechanic called Clyde who says: “Many afternoons have come and gone right here, listening to the radio, taking a break from some maintenance work.” Having played the other chapters through recently, these ideas of repair and maintenance of existing, often old and seemingly obsolete technology crops up over and over again. What are your own relationships with maintaining technology?

Kemenczy: I'm a hoarder of technology. I haven't thrown out any of my smartphones or computers over the years. I buy a lot of the vintage TV stuff that appears in Un Puebla De Nada [the interlude between Act IV and V] are based on old broadcast cameras and Sony Trimitron TVs and tube cameras and stuff like that. I like these obsolete technologies as objects. But yeah, recycling modern technology is different and important because of how disposable they’ve become. It's amazing how much cheaper a smart phone is compared to other things just because of how the market works.

It almost feels like these characters have suffered from obsolescence themselves. The miners and even Johnny and Junebug.

Kemenczy: Yeah, and Shannon is a TV repair woman who’s struggling with her business.

How do you feel about creating a work within a medium which, to an arguably greater degree than say film or music, perpetuates this idea of almost infinite technological progress?

Elliott: It's been hard thinking about how we fit into it, especially since we ported the game to consoles and some of the newer consoles have this 4K option. If you crank our game up to 4K, a lot of it disappears, the thin lines and stuff. It was extra work but Tamas built our own upscaling system so the game upscales itself in a way that preserves the lines. I just think of that moment as a way of us resisting arbitrary technological progress.

Nobody ever consulted us, the game designers, and said, "You want more pixels right?" It's like, "No, we have plenty of pixels." The game is just getting swept along by this idea of progress. I think there's something about the contemporary commodity form — talking about smartphones and obsolescence — where we've really become accustomed to the idea that everything inherently has a date of obsoletion, everything you buy is going to expire. It's all milk.

There's a video art piece we all really like called General Motors by this artist Phil Morton who is referenced in the game sometimes. General Motors is this psychedelic video art and it's pretty wild but at its core, it's basically a letter to the General Motors company. It has a lot of footage of him, the artist Phil Morton, on the phone with the dealership which sold him this van that he drove around the country with and he's really offended that GM isn't maintaining their tech. He's a video artist, he's got all these cameras, he maintains his tech.

In Act III , Lula speculates on the intention behind ancient cave paintings. She says, “Someone put that there, to keep something on the rock after she passed. A hope, a relationship, or a moment. A worry maybe… a regret.” How might you characterize Kentucky Route Zero ?

Elliott: I think it has a lot of those things in its story. A hope for sure. As you see the history of the town, the chances of this latest community are not great, to last forever at least, but there's some hope in the fact that we are compelled to keep trying again to make a better society or community.

Over email later , Kemenczy went into further detail about how higher resolutions begin to impinge on the aesthetic fidelity of a game like KR0.

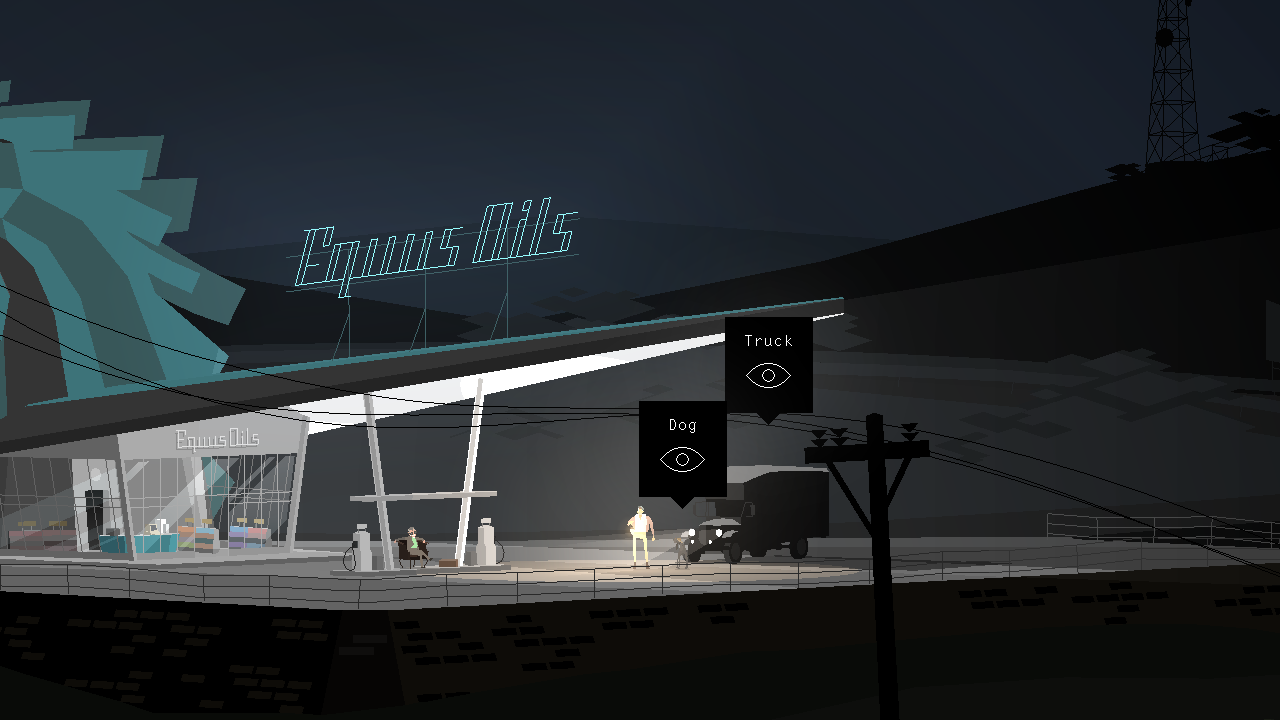

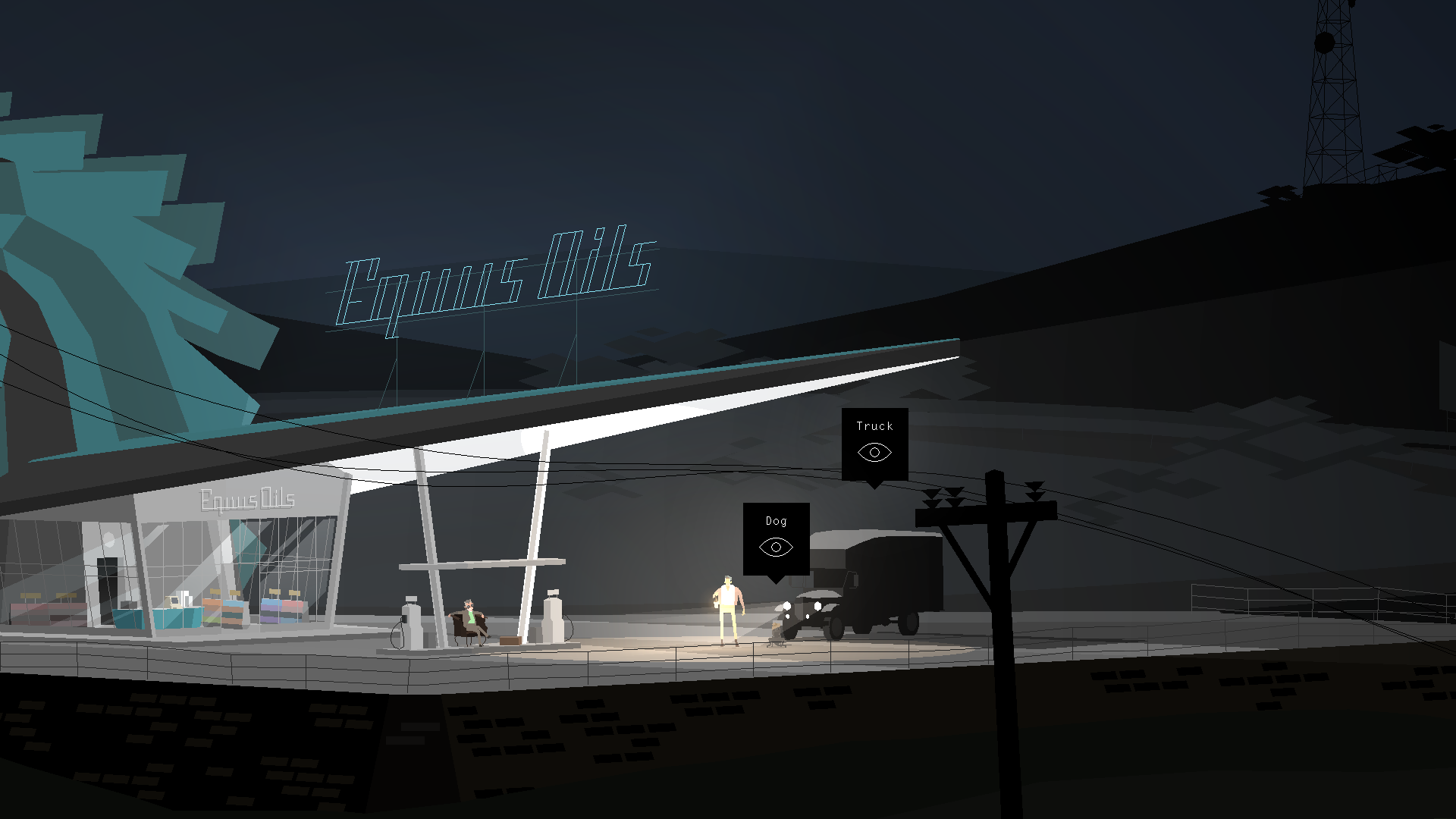

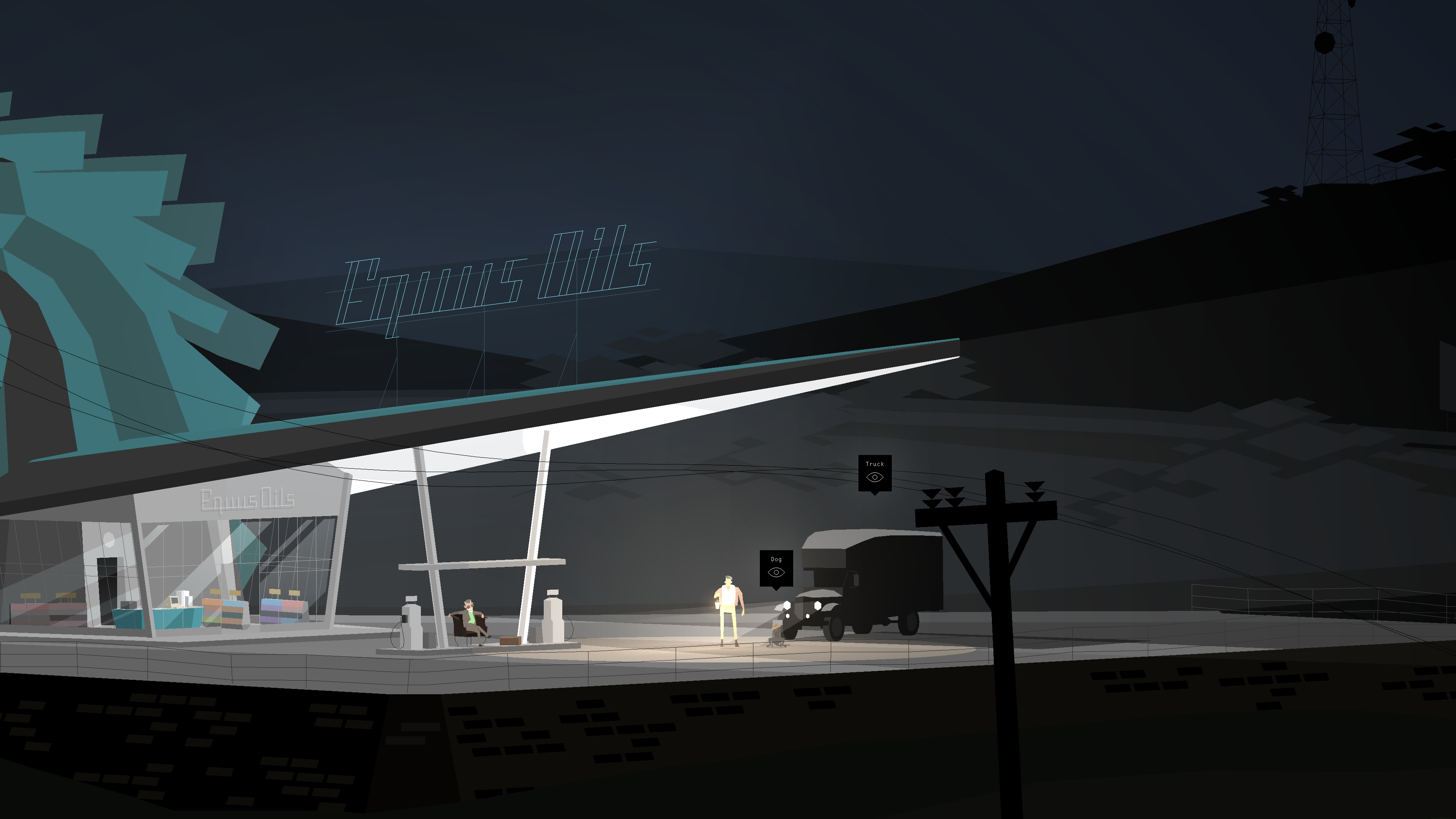

Kemenczy: Here is the Equus Oils scene rendered at various resolutions, including 4k and 8k:

As you can see, the lines start becoming very thin and light in comparison to the rest of the geometry, they get lost when looking at the image holistically and it's out of balance. We also use bitmap/pixel fonts, and we only have five sizes, so legibility starts becoming [poor] at 4k and up. Eventually, when manufacturers try to sell us even more pixels we'll never hope to see through 8k or 16k displays, the only effect that would have on our game is the line art becoming less perceptible on your display than the particles of dust on it, and text that is microscopic and illegible. This makes our game resolution-dependent, a feature that old games from the 80s and 90s depended on and designed around just like 2D pixel art games.

The game was always meant to have visible aliasing, or 'jaggies' as part of the art style. Old DOS games that achieved realtime polygons were a visual reference (both VGA and SVGA). We usually point to Another World as a visual reference. (Some more in-depth stuff about the polygons in Another World)

Maybe because KRZ shares more DNA with the likes of Another World or Elite Dangerous which rendered polygons instead of tiles and sprites of old 2D pixel games, it just didn't read as a deliberate move for some of our players, and instead maybe understood the jaggies as an oversight or something, I'm not sure. Some people were definitely upset about it early on. When we established the art style ten years ago, retina/4k displays weren't common place and we didn't really need to consider it too closely, so players could just set whatever maximalist resolution they wanted. To us, 720p is just about ideal for visual density, and 1080p is the upper limit where we think the style remains cohesive. We have now a 'classic/modern' switch which has a quality similar to running a game in VGA or SVGA mode back in the day, basically 540p or 1080p.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.