Love/Hate Reads: ‘Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus,’ Revisited

Credit to Author: John Paul Brammer| Date: Mon, 10 Feb 2020 19:56:34 +0000

When commitment feels rare and everyone’s lonely, Change of Heart is a Valentine's Week investigation of what makes relationships so hard—and how they can be better.

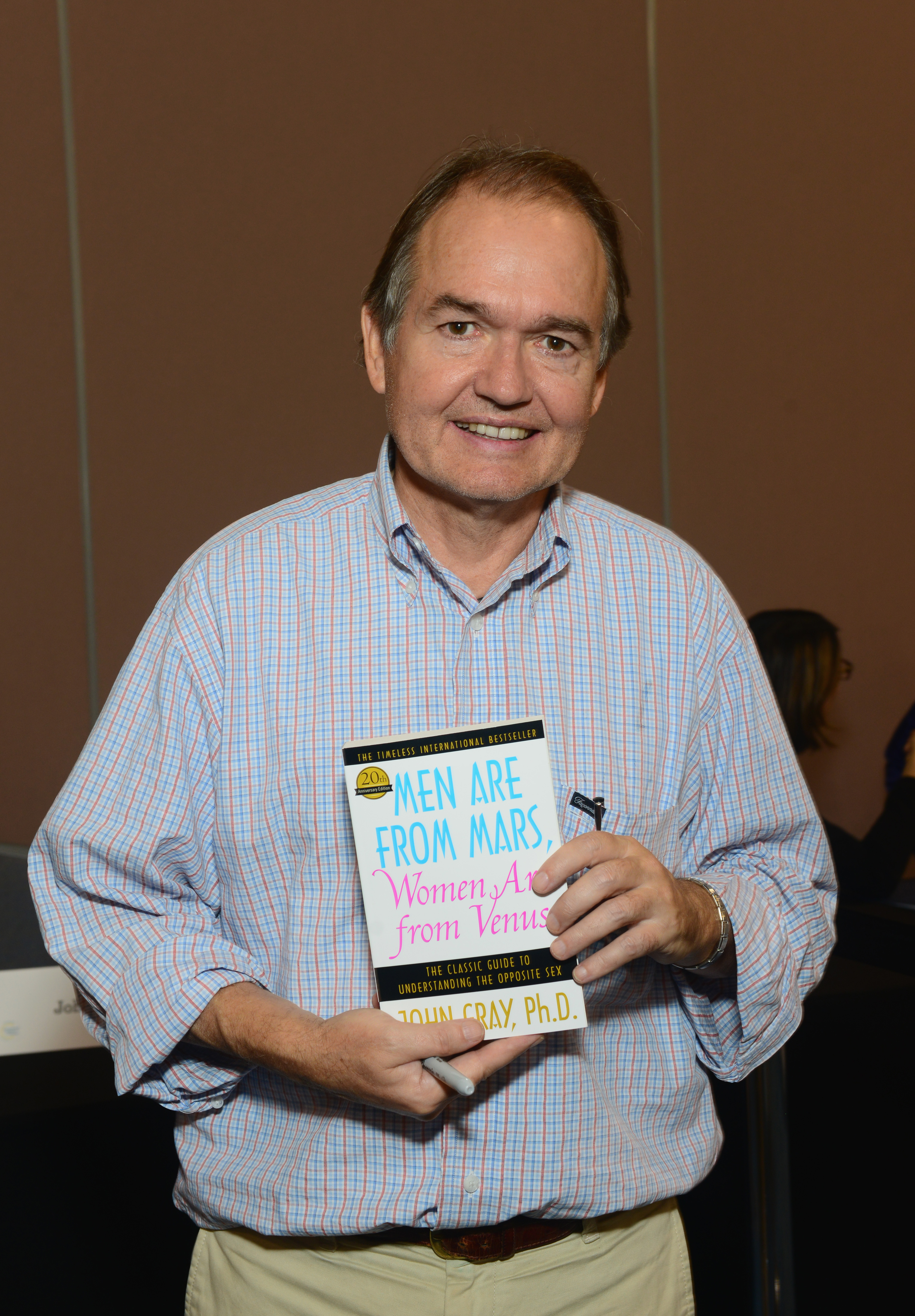

“Men Are From Mars, Women are From Venus” is undeniably a relationship guide published in 1992 by John Gray (PhD). As a homosexual advice columnist from the world of tomorrow, I was giddy at the opportunity to poke holes in a title that seemed so nakedly retrograde. And I was right, because it’s bad and I enjoyed myself. But while skewering it, I couldn’t help but appreciate what the bestseller tapped into, the thing that made it such a runaway success: a human need to memeify and flatten complicated concepts, especially ones about how different groups of people are supposed to behave.

But let’s start with the book itself, eh? The first thing you need to understand is that, far from a mere metaphor, John Gray PhD takes the whole “different planets” bit very seriously. There’s actual lore: Men on Mars were going about their Martian lives, building and achieving things, when, one day, they caught a glimpse of the women on Venus, who were braiding their hair or whatever. The men decided to invent space travel just to disrupt the women’s lifestyle and go chill with them. The men and women got along fine because, as Gray (PhD!) repeatedly stresses, “They understood their differences.”

Things went left, however, when the Martians and Venusians decided to go to Earth (on the aforementioned Spaceships for Him™) and forgot about their differences because they inhaled Earth’s atmosphere, and oxygen is genderqueer juice, I guess. (Gray submits this as a framing device, but part of me thinks he sort of buys into it wholesale and was low-key hoping it would take off.) This sets up the crux of Gray’s understanding of The Two Genders: There is a fundamental language barrier between them, rooted in immutable (space) identities. The key to overcoming it is awareness itself: cognizance of this fact, so that we might maneuver around it.

We are given a compelling opening example. Gray comes home to find his Venusian wife suffering. “I’m in pain,” she explains femininely, and adds, “You’re a fair-weather friend.” Gray, who has a small Martian brain, replies that she didn’t call to tell him she was hurting and so he couldn’t have known. They fight over this, and Gray prepares to leave his wife (unclear on for how long) when she asks him to stay. “Just be with me,” she says. Gray obliges and they hold each other, and gender is conquered for the day. “That day, for the first time, I didn’t leave her,” Gray wrote. “I stayed, and it felt great. I succeeded in giving to her when she really needed me. This felt like real love.”

It’s not super clear why she would be so mad at him for not knowing about her pain. But it makes sense in terms of Gray’s narrative objective. Women seek to share, while men seek to fix. In generous terms, women are articulators, while men are doers: When a woman hurts, she wants to open up about it. When a man hurts, he wants to locate the problem and resolve it.

The rest of the book is spent hammering this idea home. Men are drawn to careers with uniforms, we are told, because uniforms denote competence. “Even their dress is designed for this,” Gray elaborates. “Police officers, soldiers, businessmen, and chefs all wear uniforms or at least hats to reflect their competence and power.” (So there’s your answer to the big “why hats?” question, perhaps gender's most stymieing mystery of all.) Women, meanwhile, dress according to their mood. According to Gray, I would technically be “a woman.”

You have to hand it to John Gray on this front: He made his worldview very, very easy to understand. It was such an accessible idea that it became more than a book. It became a board game. It became infomercials and merchandise. It became a meme.

Flattening out the world and making it easier to understand—even while totally confusing it and incorporating extraterrestrials into your explanation—is the point of mimesis. But when memes simplify complex ideas about gender down to more easily packaged and communicated base sentiments, a lot is (necessarily) left out. Memes, in Gray's time as now, assist in facilitating the underlying desire to agree on a set identity in contrast to others, and the itch to compare and exclude and align ourselves—men are like this, women are like this, queers are like this—still exists. It openly relies on gendered assumptions that we are still comfortable making, despite knowing more about the mutability, expression, and diversity of gender across the spectrum.

Indeed, we’ve made significant strides in doing away with the “men are like this, women are like that” mindset in large part because of the writing, thinking, and increased visbility of LGBTQ people, specifically. But before we pat ourselves on the back too much for how far we’ve come, let’s also consider how people express their progressivism in mimetic ways that John Gray himself would probably see as an enormous business opportunity.

Examples abound, and I don’t consider them all high-stakes or intentionally cruel or even unfunny. Some of them are very funny to me, personally: The straights are at it again. Guys will put up a card table and throw down an air mattress and call it decor. White women would like to speak to a manager. They are all named Karen. Oh my God, I’m totally obsessed with pumpkin spice lattes. Men are garbage and furthermore don't know how to dress; heterosexuality is a disease. You get the gist.

It’s not like we’ve evolved so far from Gray's whole “space gender!” thing, either—Gray (whose credentials are dubious, by the way), harnessed a familiar desire for Why We Are the Way We Are to be both simple and divinely out of our hands. Astrology memes have never been more popular, with some (not all) interpretations imagining immutable personality types predetermined at birth. (It’s no small wonder that a member of the astro-meme community made a Problematic™ dip into phrenology last year.)

Queer people are entirely invisible in Gray’s book, even as they were disproportionately being impacted by the AIDS crisis while it was being written. Casually rendering a vulnerable swath of the population invisible seems especially egregious, in retrospect. We would never, right?

Recently, a prominent writer cracked a joke about a news story wherein a woman texted her date, “You’re not a serial killer, right?” The man ended up being exactly that, and the woman was killed. “Siri, show me heterosexuality,” the writer joked above a screenshot of the headline. The intent was, in my opinion, not malicious: Being a straight woman sucks and is dangerous because you have to deal with men, who are all too often violent with women. That’s the joke. “Ugh, being straight.”

Others pointed out that the woman was a Black sex worker and the man who killed her targeted vulnerable people like her. There are multiple factors here that give more dimension to the contextless joke—it’s not mere “heterosexuality.” It’s about class. It’s about race. It is, in reality, far afield from what relatively privileged people have to worry about or experience.

Memes imagine a universal experience, and it’s so tempting to deal in these flat, blunt "truisms"—their failure to capture reality is also why we're allured by them; they are easy. Sometimes, I'm reminded of jokes I've made about “straight people” from the gay perspective, where my imagined target is cisgender straight men, but in not making that specification, I end up including trans straight people. The universal always favors the people whose experiences are considered most important.

This isn’t me saying “memes are bad.” Memes practically raised me. But memes are no substitute for the truth, and the truth is too unwieldy to be contained in such an unreliable format. There are no shortcuts when tackling the complexities of relationships. In my capacity as an advice columnist, I take extra care to make sure I’m not relying on stereotypes or convention when answering people’s questions. I think that’s something Men are From Mars doesn’t do, as I’ve made amply clear. But I also think we haven’t evolved too far from its core argument.

We rely on the tropes and performances memes have delivered to us, and we use them as tools of community-building, as a language unto itself that can help build common identity and signal a shared understanding of an experience. Of course, I am intimately familiar with how LGBTQ people do this. But this book made me realize that, of course, the majority, the dominant culture has memes too. It’s just that they become so prolific, they often become “conventional wisdom.”

“Men are from Mars, and women are from Venus” sounds dumb to our modern sensibilities. But I bet a lot of what we’re saying today will sound that way in the future, too, if we’re lucky enough to have one. In any case, real scholars know that men are not from Mars. They go to Jupiter to get more stupider.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.