Why ‘Loom’ Remains the Hidden Gem of Lucasfilm Adventures

Credit to Author: Clara Fernández-Vara| Date: Mon, 03 Feb 2020 13:34:56 +0000

In The Secret of Monkey Island, the player meets Cobb, a dopey pirate wearing a badge that says “Ask me about Loom.” Any attempt at a conversation will be met with monosyllabic responses, but when one asks him about Loom, his eyes lit up and he erupts:

“You mean the latest masterpiece of fantasy storytelling from Lucasfilms™ Brian Moriarty™? Why it's an extraordinary adventure with an interface of magic, stunning high-resolution, 3D landscapes, sophisticated score and musical effects. Not to mention the detailed animation and special effects, elegant point 'n' click control of characters, objects, and magic spells.”

Thirty years later, the self-reference feels wistful. Loom was released just a few months before The Secret of Monkey Island in 1990, but it never came near its popularity and acclaim. The in-game ad for Loom suggests that, even at the time, it was struggling to find its audience. Loom was released a few months before The Secret of Monkey Island in 1990, and it was just as good and magical in a different way. But while The Secret of Monkey Island went on to have three sequels in the 1990s, and an episodic game by Telltale in 2009, Loom remains the sole title of what was planned as the stories of a multiverse, and the relentless fight against Chaos.

Both games were designed according to a new design philosophy for adventure games, by which the player could explore the world and experiment without being punished when they did something wrong. Things and events don’t kill the player character, the only "game over" is when you finish the game, because the goal is to get to the end of the game, rather than figuring out complex and arcane puzzles. This philosophy, explained in the manuals of both games, implicitly opposed what other adventure games did at the time. Players had to save their games constantly – there was no autosave – because their characters could die if they chose the wrong path or didn’t solve a puzzle on time. Loom and The Secret of Monkey Island encourage players to live in the world, solve puzzles at their own pace, talk to everyone, explore, try things without worrying about their progress. This new way of thinking about adventure game design laid the foundation for current adventure games – the Samorost series, Kentucky Route Zero, Oxenfree, Night in the Woods, Lamplight City, to name but a few, all focus more on exploring the world and the characters, rather than solving the puzzles and “getting it right”.

Loom remains a key influence for many game designers, writers, and critics, including myself. In spite of re-releases and re-visitations, however, the game has remained under the shadow of Monkey Island except for those of us who played it in the 1990s.

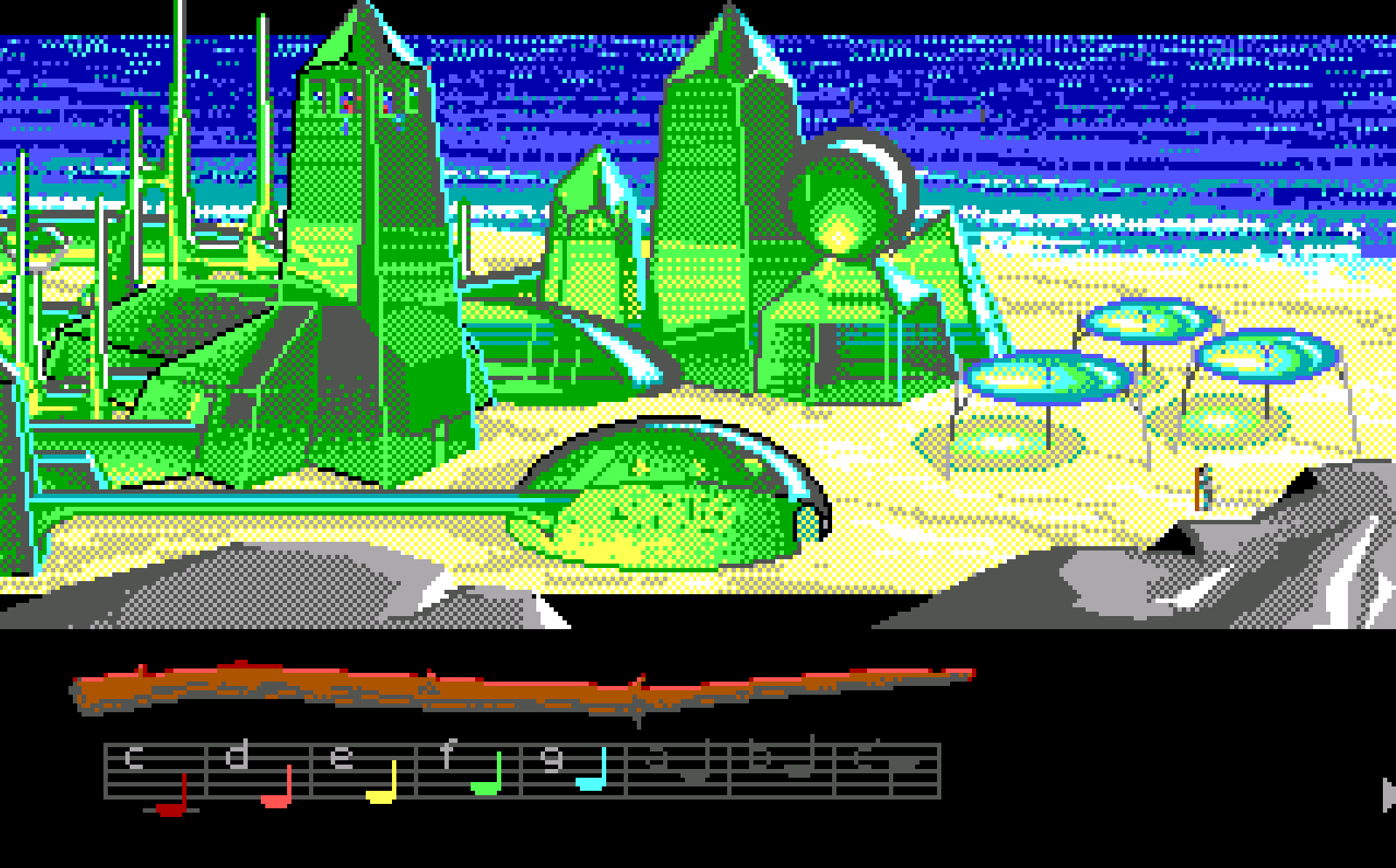

Cobb’s advertisement gives us a hint of why it was not as commercially successful, in spite of its artistic achievements. The description of the game only talks about the technical aspects – animations, music, controls – but not what the game is about. Loom was technically impressive – the original pixel graphics depict a wonderful world in only 16 colors; the soundtrack also made a wonderful use of the sound card by including a variety of pieces from Tschaikovski’s Swan Lake.

The game takes its time to establish the world, with elegance and poise, in contrast with the riotous humor of Monkey Island. Loom is not bombastic, it has funny moments but not laugh out loud. Its fantasy world will not blow you away immediately – but it will steal your heart if you persevere.

Truth is, the story of game is one of its best assets but it doesn’t have an easy elevator pitch—it takes place in a world, where Guilds such as glassmakers, blacksmiths or shepherds have settled in different cities. The game starts in Loom, the Island of the Guild of Weavers, who weave fabric as well as control the fate of the world. The player controls Bobbin Threadbare, the youngest member of the Guild who is the key to bringing on the apocalypse but doesn’t quite know it yet. At the beginning of the game, the Weavers realize that the Pattern of the world is fraying, so they transform into swans and abandon the island, leaving Bobbin behind. The goal of the game is to find where they went, which takes the player across a variety of fantasy locations.

The world of the game is enchanting, exotic, and dangerous—Lucasfilm Games’ usually veered away from space marines, fairy tales, crime stories, and generic fantasy settings that appeared in other games. The setting is an original fantasy world that makes references to works beyond genre fiction – apart from Swan Lake, the Weavers echo how the Fates of Greek Mythology wove people’s destinies, and the green city of the Glass Blowers is reminiscent of Wizard of Oz, to name but a few. It is the main reason to play the game, but it is also difficult to explain what makes this world stand out in a succinct way, which explains why poor Cobb found it easier to gush about the technical aspects of the game.

We are in a world of weavers, and the way that we interact with the world is not using a verb menu but an object in the world – a musical distaff. Early in the game, we learn the melody that allows the player to open things – we click on the object and we play the melody on the distaff. To carry out the opposite of an action, such as closing something, we can play the melody backwards. The melodies have four notes and are different whenever the game starts, so the player has to take notes while playing – the manual included a section to write the melodies down. At the beginning of the game, the distaff only lets us play a few notes; as we explore more of the world and solve puzzles, we unlock more notes, which allow us to play melodies for more complex actions. These actions have an interesting variety – while open/close are standard verbs in games, there’s also “dye (green)”, “awake”, “turn invisible”, “sharpen / make blunt”, and “transcend” among others – a variety of actions that remains unusual in mainstream games. The more actions we can play on the distaff, the further we can go and the more threatening the world gets. The mechanics are a beautiful metaphor to express how Bobbin is growing up – as he learns new spells in order to deal with an increasingly complex world, similar to how in the Zelda series every new item we can equip allows us to do new things and defeat stronger enemies.

The original release also included a prologue, which was a 30-minute drama recorded in an audio tape. The prologue tells the story of the city-states of the Guilds as an industrial activity while the Weavers retreated to their island, the transgression of Lady Cygna Threadbare in having her son Bobbin, which set up the unravelling that will take place in the game. This tape evidences the narrative ambitions of and the epic scale of Brian Moriarty’s story. The tape was not included in most international versions of the game and the prologue was left out of the CD release of the game, which on the other hand included voiceover for all the cutscene dialogue. Nowadays, the audio drama would have been released separately, as part of a transmedia stragegy to promote the game—maybe as an animated video, or a web comic, or even a short promotional game. The prologue is part of the story that may not be essential to understand the story, but that helps understanding the world better, making it vivid, and create expectations about it. In a way, it was ahead of its time.

30 years on, Loom has aged unevenly. The technical aspects that were touted back then, which are still listed in the blurbs if you purchase the game online, do not seem as impressive. The versions now available for sale are the 256 color version with voice over, which doesn’t look as beautiful and stylized as the original release, as if more modern technology made the game better. In one of my narrative design classes, I play the beginning of the game with my students to show how to introduce players to new game mechanics without a tutorial, and how to help players understand the backstory of a game as part of the gameplay. Although there is one long cutscene that retells to some of the events in the audio drama, it is perfectly possible to follow the story of the game without it. What the early part of the game doesn’t get across, however, is its wonderful expansive world, the characters that populate it, or the smart puzzle design, which is designed to be accessible. There’s many compelling characters along the way – a glassmaker who only cares about his business and not worrying about bringing the end of the world, a sassy female dragon who refuses to blow fire, and Cobb himself, who appears as a cleric. Cob (his name in this game) is an awful henchman who bullies people around… and dies a horrible death by peeking under Bobbin’s hood. Cob’s death is not the only horrible thing that Bobbin does – until he realizes that the world is not only fraying but disintegrating, and he needs to help repair it.

Loom challenges us now because it is literary, it demands our attention and our time in ways that are unusual nowadays. But it also rewards the player who takes the plunge to follow the story through an original, dangerous world until Chaos is unleashed.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.