Lowe: Eleven NBA things I like right now

Terry Stotts tries to give the game ball to Damian Lillard after his first triple-double, but Lillard passes it to Carmelo Anthony instead for moving up the scoring list. (0:36)

Here are 11 things — all “likes.” This is a week to appreciate the beauty and ruggedness of the game.

The power of Giannis Antetokounmpo: He can morph into any player type depending on what Milwaukee wants, and perform each at an All-Star level.

Need him to masquerade as a traditional drop-back center so you can play maximum shooting around him?

Uh oh. That is, like, expert-level center pick-and-roll defense from someone who is not a center. Giannis flashes at RJ Barrett, extending his giant left arm toward Barrett’s face. That freezes Barrett. He slows and picks up his dribble. With Antetokounmpo appearing to commit, the lob to Mitchell Robinson should be available.

But just as quickly as Antetokounmpo appeared in Barrett’s driving lane, he’s back at Robinson’s side. Barrett notes that on his descent, and flings a desperate layup. Antetokounmpo devours it.

You play good defense by reacting on time to each offensive action. You play great defense by manipulating the choices the offense makes. Opponents are shooting an absurd 43.5% at the rim with Antetokounmpo nearby, the lowest figure among all rotation players who challenge at least two shots per game. Ridiculous.

Mike Budenholzer has leaned more into Antetokounmpo-at-center lineups this season, even those that don’t include Ersan Ilyasova as a second big who can guard centers. Antetokounmpo is taking that assignment more often alongside Ilyasova, anyway.

On offense, Antetokounmpo plays the same role in every lineup construction: taller and more explosive variant of the point-forward prototype. But that length opens up possibilities — shots, passes, pockets of air — that exist only for him:

You see that every game: Antetokounmpo dribbling side by side with his defender, not quite escaping the shot-blocking radius. But then he reaches that arm as far as it goes, and an angle to the rim appears that wouldn’t be there for any other player.

He does the same thing with passes. He tightropes the baseline, leans out of bounds, unfolds his arm that way, and bam — suddenly he has access to all kinds of inside-out dishes. The court is 94 feet long for most players, and about 100 feet for Antetokounmpo.

Cherish this guy every night. We have never seen anyone like him.

A lot of teams would have considered Robinson a finished product as a shooter, and focused on rounding out the rest of his game.

The Heat gave equal time to turning Robinson’s one “A” skill into an “A-plus.” Rival organizations have taken notice, and expressed admiration for Miami’s approach.

One part of that approach: turning Robinson into a serial screener, on and off the ball. Ace shooters from Kyle Korver to Stephen Curry learned to use the threat of their jumper to create open looks for teammates by screening for them. Not every shooter is willing. Some can’t read the game well enough to set them in the right places, at the right times.

Robinson is a roving menace:

One back screen for Jimmy Butler generates an open corner 3 for Kendrick Nunn. Robinson’s defender — Barrett — won’t risk straying an inch from Robinson; he can’t help on Butler’s cut. The job falls to Nunn’s defender. Boom.

Robinson does not touch the ball, but he creates this shot.

Another classic:

Meyers Leonard feigns a pindown for Robinson, but it’s a ruse! Robinson fakes the curl, and dives into his own pindown for Leonard.

Robinson even has a burgeoning pick-and-roll partnership with Bam Adebayo — little guy screening for chiseled strongman:

I am a sucker for any inverted pick-and-roll. This has a chance to become the Eastern Conference version of Jamal Murray screening for Nikola Jokic.

Put Robinson in the 3-point shootout, or we riot.

Wood’s per-minute numbers had always popped, but his strong play in Detroit marks his first sustained success as a rotation mainstay.

He has flashed a well-rounded, nimble offensive game playing both big-man positions for a Pistons team that seems to need a new rotation every night because of injury. Wood has hit 37% from deep on decent volume, and more than half of his long 2s.

He’s taking big men off the bounce, and drawing heaps of fouls with a bruising, shoulder-first face-up game:

That is quite rude. Wood is averaging seven free throws per 36 minutes. Detroit has outscored opponents by four points per 100 possessions with Wood on the floor — and lost all other minutes by 5.9 points per 100 possessions. There is a ton of noise in those numbers, but nothing to suggest Wood’s impact is hollow.

Detroit’s defense gives up fewer profitable shots — 3s and attempts in the restricted area — with Wood on the floor.

Wood might be semi-trapped between positions on defense — too slight to man the middle, not quite rangy enough to chase stretch power forwards. That might prove more troubling as a starter. It hasn’t really manifested this season, though Detroit’s offense has been mediocre with Wood and Andre Drummond together.

Wood has carved out a place in the NBA. He’ll be a free agent this summer, and a lot of teams are curious whether the skidding Pistons — six games out of the eighth spot — might trade Wood rather than risk losing him for nothing.

These guys developed beautiful chemistry last season. They have added wrinkles upon wrinkles, growing one of the league’s most dangerous two-man games from the compound effect of McDermott’s shooting and Sabonis’ passing.

The simple act of McDermott sprinting around a Sabonis pick busts entire defenses:

Opponents have no good choice, other than having two elite defenders who execute with airtight perfection. Fall behind chasing McDermott over that screen, and he’ll rain fire. Dipping under is not an option. Trap McDermott, and he’ll slip a pass to Sabonis, allowing a genius big man facilitator to play 4-on-3. Switch, and Sabonis mashes some poor sap in the post.

Climb on McDermott’s back early, and he might veer into the paint before even reaching Sabonis:

Only 11 duos have paired up for more off-ball screening actions, and the Pacers average about 1.17 points per possession on any trip featuring such a play — a mark that would lead all half-court offenses, per Second Spectrum data. The Pacers are plus-5 points per 100 possessions with Sabonis and McDermott on the floor.

Someone will lose minutes with Victor Oladipo back, but it shouldn’t be McDermott.

I don’t have a ton to work with here. Bazley is shooting 30% from deep and 45% on 2s for Oklahoma City. He has 39 turnovers and 28 assists. It is really hard for a rotation player — especially a non-center — to record so few dimes.

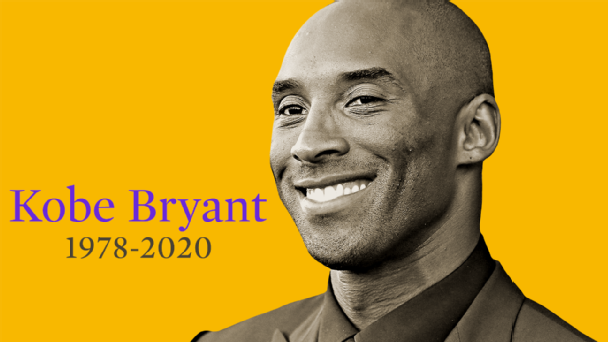

Lakers legend Kobe Bryant, his 13-year-old daughter, Gianna, and seven others died in a helicopter crash early Sunday morning.

• Adande: Kobe’s power to control the narrative

• Lowe: Kobe’s beautiful and maddening greatness

• Voepel: Gigi Bryant’s own hoop dreams

• Shaq, West in tears as Kobe honored

But there is something about Bazley. The rookie moves his feet on defense. He changes direction without conceding momentum. He seems to read the game — to rotate without falling behind, pausing to figure out his next move, or zipping to the wrong place.

Combine all that with a 7-foot wingspan, and you have the ingredients for an interesting multipositional defender. It is hard to drive around Bazley when he arrives on time, arms spread wide.

He’s also a smart cutter on offense, with a knack for anticipating when an alleyway will open.

Teaching feel is harder than teaching skill. I am always intrigued by rookies who show an early foundation of feel.

The “Spain” pick-and-roll has swept the NBA over the past decade. The Mavs use it the most. It is basically a normal pick-and-roll, only with a third player — Tim Hardaway Jr. below — back-picking the man defending the screener (Ivica Zubac, technically guarding Kristaps Porzingis):

The ideal outcome is for that back screen to spring Porzingis for a rampaging lob dunk. Defenses know that. Over the past two years, they have gotten smarter keeping that defender — Zubac — deep in the paint, urging him to burrow below the back screen. That way, the defense can play the central pick-and-roll 2-on-2 and stay home on everyone.

Offenses have found a bunch of counters for that. The most obvious: If Zubac is hanging way back there, why should Porzingis rim-run at all? Just flare out for a 3-pointer!

Drain one or two of those, and the defense has to scrap its plan. It might pressure, exposing passes and driving lanes. It might switch into bad mismatches.

Another favorite: when the back-screener slips out of his pick early, and darts away for an open triple. Bojan Bogdanovic is a master at this:

The instinct of Bogdanovic’s defender is to linger in the paint in case of a crisis there. Bogdanovic leverages those good intentions against the defense.

When defenses know the back-screener is a threat to pop for 3s, they sometimes try to engineer triple-switches on the fly. The more complex the switchcraft, the greater the likelihood of a mistake.

One sub-note: Before the Mavs acquired Willie Cauley-Stein to fill some of the Dwight Powell void, Porzingis was logging more time at center as the lone big in smaller lineups. (He is still starting there.) The Mavs and Porzingis seem ambivalent about that arrangement. It does open driving lanes for Luka Doncic; there is no second big man lurking on the baseline as a help defender.

Doncic took advantage right away after Powell’s injury, attacking one-on-one in wide-open space. He’s so strong, and so crafty, he doesn’t need to get past his guy to finish around the rim. Just getting him backpedaling is enough.

Lillard is a bad, bad man. I would have included his stats from Portland’s past six games, but my laptop caught fire when I looked them up.

Lillard has some Kobe in him, doesn’t he?

No strand of Chicago’s strange, disappointing season carries more long-term importance than Markkanen’s stagnation. Chicago’s announcement last week that Markkanen would miss at least four weeks because of “an early stress reaction of his right pelvis” was almost a relief. It is clear — has been for a while — Markkanen played most of this season dinged up.

He never found a groove on either end. His place in Chicago’s offense became murkier. He got fewer opportunities in the pick-and-roll, and looked sluggish with the ball. He drifted.

I was high on Markkanen last season. He looked like a potential strong No. 2 on offense — a pick-and-pop big that could bend conventional defenses. I remain confident there is a good player in here.

This is a week to celebrate cool stuff, and Markkanen is a sneakily stylish defensive rebounder. He’s 7 feet tall, with long arms and an appetite for nastiness. He is really good at coming into the scrum from nowhere, out-leaping everyone, and snatching rebounds from over the heads of ground-bound enemies. It just looks awesome:

Markkanen’s defensive rebounding rate hit a career low this season, but the advanced data is interesting. Chicago’s team rebounding hovers around the same (below-average) level whether or not Markkanen is on the floor. Jim Boylen’s aggressive blitzing scheme often leaves his big men flying far from the hoop, out of rebounding position.

Tracking data from Second Spectrum has Markkanen snaring more opponent misses than expected based on his positioning when a shot goes up — perhaps confirming the eye test that he is a skilled and aggressive board tracker.

Anyway: Markkanen is an interesting and crucial player. Get healthy, big fella.

At 22, De’Andre Hunter is the oldest of the three young wings handpicked to surround Trae Young. Cam Reddish is 20. Huerter is 21. It is going to take a long time. You have to remind yourself of that.

Be careful pigeonholing Huerter as a spot-up threat. He is running 21 pick-and-rolls per 100 possessions this season, up from about 12.5 last season, per Second Spectrum. He has good vision and timing as a passer — including the ability to whip crosscourt lasers with either hand. He should grow into a capable secondary ball handler.

He also has a fun feistiness to his game. He’s 6-7, and plays bigger than opponents seem to expect. He enjoys lunging into rebounding battles, and he’s snagging an above-average number of defensive boards for his position — and many more than expected given his starting point when each shot goes up, per Second Spectrum.

He’s a physical defender who knows how to use his length without fouling. Take Huerter lightly, and he might toss your stuff right back in your face:

Huerter is shooting 39% from deep, and every peripheral in his game is trending the right way. Lloyd Pierce has dabbled recently in starting his young core lineup: Young, Huerter, Reddish, Hunter and John Collins. I wouldn’t mind seeing more of that as we hit the stretch run. (That group is plus-9 in 116 minutes — too few to mean anything.)

The Hawks have big decisions to make about Collins — what position he plays, what sort of frontcourt partner he requires, and how committed they are to him as a foundational player. Collins is eligible for an extension this summer, and I’d wager his representatives demand something close to the maximum salary.

The Young-Collins pick-and-roll, surrounded by shooting, is a problem. But opposing offenses attacking the Young-Collins duo in the pick-and-roll is a problem, too — especially with Collins at center.

Brooks has his flaws. He’s thirsty for long 2s, and he doesn’t shoot them all that well. He can bulldoze through almost every guard, but his finishing at the rim once he gets there is only so-so.

But damn, do I love watching this dude play. He brings an old-school toughness and physicality that seems genuinely unpleasant for opponents. He leaves a mark. Guard this guy — or have him guard you — and you feel it the next day.

He relishes contact. Look at this:

That’s Julius Randle. Randle has warts, but the man is a freight train. You think it’s fun for a wing giving up some weight to jostle on the block with Randle?

It’s probably fun for Brooks. He fronts Randle, and refuses to concede that position even when Randle hip-checks him — a jolt that would dislodge a lot of guards. That is a winning play.

The tradeoff to Brooks’ NFL style is a heap of fouls, but I’ll take a few hacks any day if it comes with this kind of effort.

Oh: Brooks is also Memphis’ third-leading scorer, a point behind Ja Morant and Jaren Jackson Jr., and he poured in 21 per game in January — tops on the team.

This hints at the promise of Garland:

Ante Zizic sets that pick a few feet across half court, unlocking the possibility of an extra-long, Lillardian pull-up. Gorgui Dieng is so deep in the paint, Garland can dribble almost to the arc. But he has hinted at longer pull-up range; only 16 players have dared more shots between 26 and 30 feet from the rim, per Second Spectrum.

Garland has launched 121 total pull-up 3s, 25th in the league, and 127 catch-and-shoot triples — an even split, suggesting Garland is confident in the pull-up. He hasn’t shot it particularly well, but he looks comfortable.

Everything changes once a ball handler establishes that shot as a threat. Big men defending Garland’s screeners have to venture beyond the arc, out of their comfort zone. Garland’s defenders get antsy. They listen for footsteps. They gird themselves to chase Garland over the pick. In their impatience, they might open their stance early — revealing a driving lane. They become susceptible to fakes.

Garland already understands this. Kevin Love is an expert screener who sews even more confusion by flipping the direction of near-logo picks at the last second. Things like this start to happen:

Garland has some spice and craft to his game. The hesitation dribble into a one-handed gather is delicious. He has a real chance.

Garland has a bit of a clearer long-term trajectory than Collin Sexton, his backcourt partner. He’s ahead of Sexton as a passer. Garland can pound the ball — a Sexton bugaboo, too — but there is a bit more purpose and vision to it.

There are early worries around the league about whether Sexton and Garland can coexist. Cleveland doesn’t have to panic yet. They are so young. But it’s never too early to start asking the question.