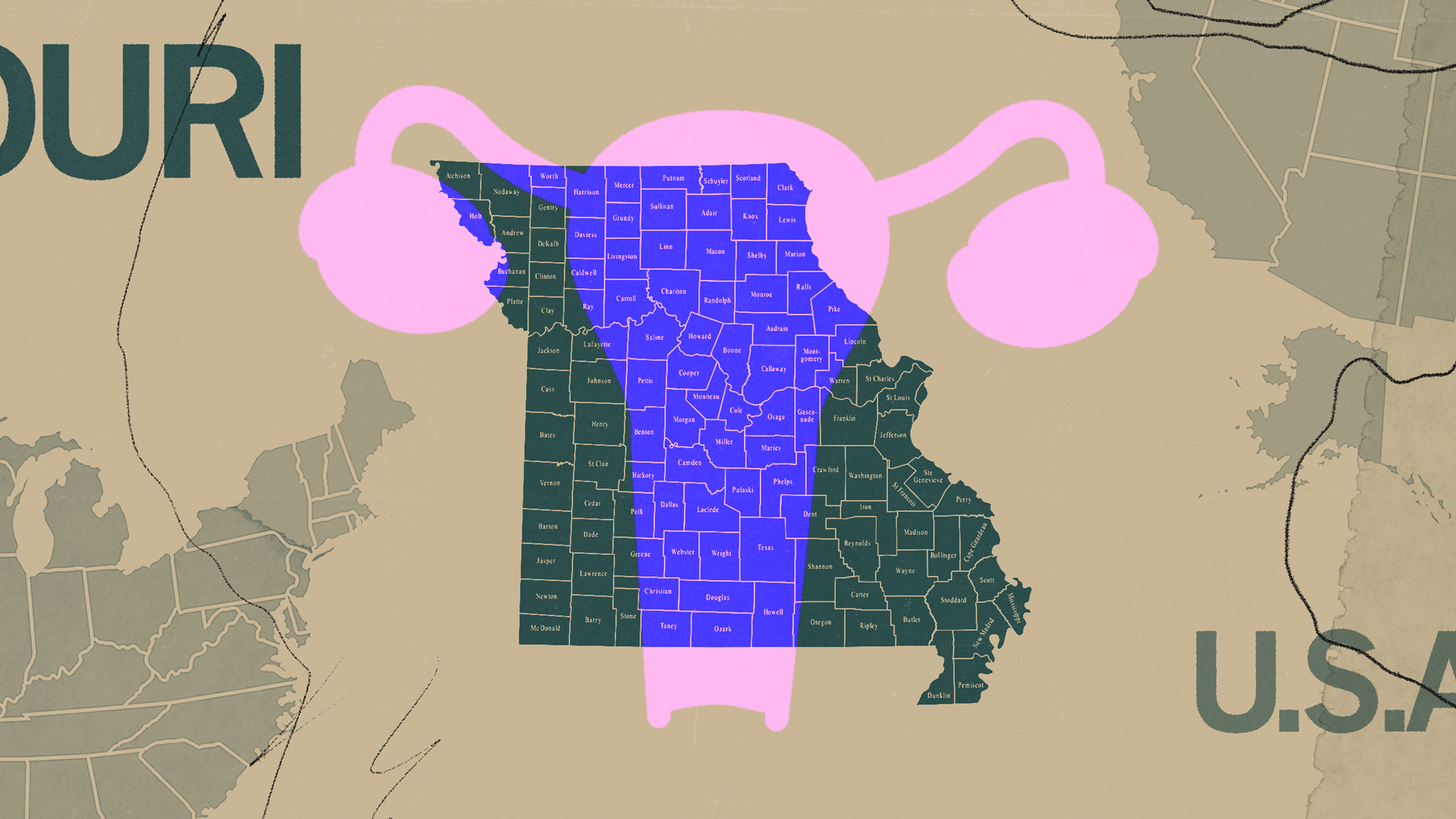

What It’s Like to Get an Abortion in Missouri

Credit to Author: Claire Lampen| Date: Thu, 30 Jan 2020 23:28:28 +0000

For years, Missouri’s acutely conservative attitude toward abortion skated under most people's radar. This was despite its longstanding commitment to policy that mirrors what’s on the books in more hostile states, like Texas. In summer 2019, however, when the state health department (the same agency that kept a spreadsheet of women’s periods) decided to arbitrarily reinterpret an old “informed consent” law, the fate of Missouri’s last abortion clinic—Planned Parenthood of the St. Louis Region—jolted into limbo. On the brink of becoming the first state without a single abortion clinic since Roe v. Wade and with an (enjoined) 8-week ban working its way through the courts, Missouri grabbed national headlines. But really, it has always listed among the states most hostile to abortion rights.

In 1986, Missouri became the first state to require abortion providers secure admitting privileges at a nearby hospital so that, in the exceedingly rare case a patient required emergency medical attention, they could be whisked to a local ER. It’s a roundabout means of shrinking the provider pool, and an arbitrary one: Abortions rank high among the safest medical procedures available, and ERs do not make a habit of turning away people in pressing need of care. That would be illegal. Yet baseless restrictions like these have piled up in Missouri, meaning that—with the exception of a very brief respite—the state has relied on one abortion provider since 2011.

What Missouri state law says about abortion:

- Only physicians may perform abortions, meaning providers like nurse practitioners are prohibited from offering the procedure.

- Patients must undergo mandatory, in-person counseling with that physician 72 hours prior to termination. This means two separate trips to the clinic, to absorb medically inaccurate information designed to change the patient’s mind.

- The patient must undergo a state-mandated pelvic exam, which is usually up to the discretion of the provider. Missouri requires this even for medication abortions which don't involve any instruments in the uterus, so Planned Parenthood in St. Louis refers those patients to neighboring Illinois to prevent the exam being forced on them.

- Insurance—whether public or private—covers abortion only in cases of life endangerment. Although privately insured people can theoretically purchase riders to help pay for the procedure, that would require them to anticipate their possible need for an abortion, and also for private insurers to actually fulfill that need. No private insurer offered riders in Missouri in 2017 or 2018.

- Medicaid will only cover abortion in cases of life endangerment, or when a pregnancy results from rape or incest.

- Providers are banned from prescribing medication abortion via telemedicine consults.

- A minor seeking abortion must secure parental consent beforehand.

- Abortions after fetal viability (around 24 weeks) are legal only in cases of life endangerment or severe health complications for the pregnant person.

- Patients may not terminate to avoid genetic anomalies, or to select for race or gender, which—with particular respect to those last two—all available evidence suggests no one is doing anyway.

- Facilities providing abortions must meet the same physical standards as ambulatory surgical centers, inflicting strict spacial requirements on their halls and doorways, and limiting who can work there.

- Physicians must have admitting privileges at a hospital within 15 minutes of their facility.

What it’s like seeking an abortion in Missouri

This is one person’s story.

Ashley, now 33, was 20 weeks into a wanted pregnancy when she went into her OB/GYN’s office for an ultrasound in August 2018. Her doctor told her she had developed an amniotic band—a strand of the amniotic sac branching off, potentially entangling the fetus’s fingers or limbs—but not to worry. Against her doctor’s wishes, Ashley and her husband sought a second opinion, and discovered a rare genetic disorder called heterotaxy that stood to kill both Ashley and the baby. Abortion remains illegal in the state past 24 weeks unless the mother's life or health is at risk, with no exceptions for fetal anomalies. Ashley wound up terminating just before that window closed. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

When did you decide to have an abortion?

It was about 21 weeks by the time we were able to set up the [second opinion]. They did an ultrasound, then pulled us into this little room and told us, ‘It’s not an amniotic band. But there are a lot of things wrong.”

Our daughter had heterotaxy, which is where all your organs are in the wrong spots. Her heart was on the wrong side of her chest, she had no left side of her heart at all, no left chamber. The capillaries that had formed were microscopic and they weren’t working. All her intestines were in different spots, malrotated and not connected. Her stomach was on the wrong side. Her kidneys weren’t connected. When they were telling us all this, a social worker in the room said, “You know, abortion is an option.” I’ve always been pro-choice: I’m 33 years old, pro-choice my entire life. But I felt so sick, because I thought, Oh my god, this is my baby. I even said "that’s not an option, I don’t want to do that."

But we learned more about it, we learned that she would need three major organ transplants at birth, if she survived the pregnancy. Babies don’t get three organ transplants. Nobody gets that. And her life expectancy would’ve been 10 years, at best, and that still doesn’t account for risk of lack of air, brain damage [until any transplants took place]. I was worried for my living children, and even myself. My body was making her organs work, and they think that if I would’ve carried her to term and birthed her into hospice, I would’ve gone into heart failure.

We terminated the day before my 24 week-mark, which is the law in Missouri. My best friend came over and watched my two youngest children. She spent the whole day with them, and we went to WashU hospital. We did a dilate and evacuate, which is a two-day procedure. You go in and they stick these sticks inside your cervix, which swell. I live close [a 45-minute to hour drive away] so I was able to go home; if you don’t live close, you have to stay in a hotel, in case you need medical attention.

Were you worried you would fall outside that timeline?

We were extremely worried. Even afterwards, through all the care that we got and all the sympathy we got from the doctors, we still felt like we were rushed. It was almost like after every single appointment, they would come back in and be like, “Okay, what do you think about it now? Do you still want the abortion, are you okay with it? I’m sorry, but you have to make this decision.” Because we only had three weeks. Because you have to sign the paperwork, and then you have the 72-hour [waiting period before] they can put the sticks in, and then that’s still another 24 hours [before] they can do the procedure.

We did [echocardiograms], we did blood tests, we did the amniotic fluid tests. We did everything to make sure that this was real, and it all had to be rather rushed.

How much did the abortion cost?

My husband owns a business in Colorado, although we live in Missouri. Our insurance is out of Colorado, so our insurance was able to cover some of it, which is why we were able to have it in a hospital. Even after that, we still paid about $12,000 out of pocket, just for the D&E [no hospital stay]. We just got it paid off not too long ago. And that was offensive, but the most offensive part, we actually had to have a check when we went to the hospital. It was like a down payment, we had to have a check for…a couple grand, like a deposit.

If our insurance hadn’t paid for [part of] it, we would’ve had to go to Illinois [which doesn't have a waiting period and has more lenient rules after viability]. I was 24 weeks pregnant, and I’m very small naturally. I was scared to go past [abortion clinic] protesters, obviously pregnant. [crying] Thankfully we didn’t have to do that.

What was the counseling appointment like?

The [doctor was] literally like, “Hey, we have to hand you this pamphlet; I have to tell you what’s in it, but I don’t agree with it. This is false: You are not going to get breast cancer, you are not going to this, this, and this.” They really made sure it was something that we were okay with. They went through all the diagnoses with us again, and we talked about it, we talked about our living children. It was really warm and understanding, and it felt nice, honestly. It was three women: the doctor who performed it came in, the nurse who would be there came in, and they just were very open about what would happen.

[The counseling] lasted probably about two hours, but they would’ve stayed there as long as we needed them to. We told them, okay we’ll go ahead with the termination, but we hadn’t done the echoscan yet. We decided we wanted the echoscan, just to be sure, so then we had to wait for those results. I was already quietly crying, and I knew that if I said anything, I would just lose it. And a [different] nurse came in and she kind of looked at me, and then walked out of the room. I heard her say to somebody else, "she’s in there crying." And then the other lady goes, “Well, because she knows it’s wrong.” And I was just in shock.

What was the actual appointment like?

Everyone was so nice the day of. I met everybody who was going to be part of the procedure. They wheeled me into the [surgical] room, my husband couldn’t be there because it was a sterile environment, and the nurse asked, “Do you want me to hold your hand throughout the whole thing?” I said yes, and she held my hand, and they gassed me. I don’t remember any of it.

Is there anything else you’d like to say about the experience?

[Crying] It was the best decision for her. Medical intervention would’ve been pointless. If she survived, we would’ve had to watch her suffocate because her capillaries, she had no lungs, they didn’t work. We would’ve had to watch her turn blue and die. Everything we did, we did out of pure love. For her, for our living children, and for ourselves.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.