Haida masterpieces donated to the Vancouver Art Gallery

Credit to Author: John Mackie| Date: Fri, 24 Jan 2020 22:45:17 +0000

Charles Edenshaw is arguably the greatest sculptor in Canadian history. Working in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Haida carver crafted dazzling, elegant, impossibly intricate pieces that took traditional Haida art into whole new realms.

New York art dealer Donald Ellis compares him to Michelangelo.

“He’s the most important 19th century Indigenous artist in Canada, possibly in North America,” said Ellis from New York. “He was the leader of the Haida people at a time when the smallpox epidemic hit. He was creating all this extraordinary work when the world around him was crumbling.

“We believe he was possibly the first Indigenous person on the northwest coast, maybe in North America, to make a living producing art.”

Edenshaw’s artworks are in many of the world’s great museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Field Museum in Chicago, and the Berlin Ethnological Museum in Germany.

Oddly, in Vancouver, the major Edenshaw collections are at the Museum of Vancouver and the UBC Museum of Anthropology, not the Vancouver Art Gallery. First Nations art wasn’t considered art in the gallery’s early years, it was considered ethnography.

The Vancouver Art Gallery had a groundbreaking Edenshaw exhibition in 2013. But it had to borrow the art for the show because the VAG only has two Edenshaw pieces in its collection, a model argillite totem and a Haida hat that his wife made and he painted.

The size of the VAG’s Edenshaw collection is about to jump, because Ellis has donated five Edenshaw works to the gallery: two bracelets (one gold, one silver), and three silver spoons.

“Both the bracelets have very important provenance,” said Ellis.

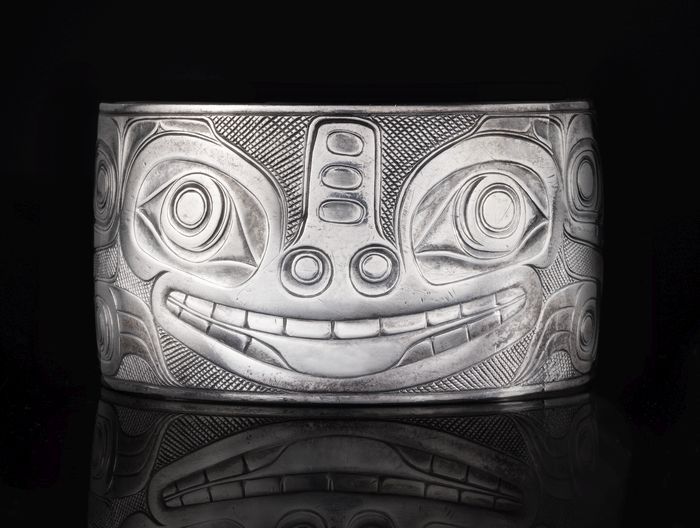

“Edenshaw gave the large silver bracelet to Chief Shakes (in Alaska) in the 19th century, which was then given to his daughter, Mary Ebbetts Hunt. She was Tlingit and brought Chilkat weaving to Vancouver Island.”

She passed the bracelet down through her family.

“The gold bracelet remained in the Edenshaw family until they sold it a little while ago.”

The VAG’s acting director, Daina Augaitis, was co-curator of the 2013 Edenshaw exhibition. She said his best work — a trio of platters that weave a single story — is simply exquisite.

“The design of them is so sophisticated they just take your breath away,” said Augaitis.

Of the Ellis donation,” she said, “I would say that the perhaps the most extraordinary is the wider silver bracelet that (belonged to) Chief Shakes. That’s a frog design. His ability to make the designs, make the drawings, but also his execution (is remarkable) — he had such a steady hand.”

“Do you know what push lines are?” asks Ellis. “In engraving, a push line is when you’re drawing a line with a small chisel in silver or gold. You stop and then you start again, and if you look under magnification, you can see a little ridge where the hand comes up when it stops, and moves down when it starts again.

“Edenshaw doesn’t have push lines. His hand was so certain that he could draw an ovoid in one movement without stopping and starting again. And when you look at all his contemporaries, you see push lines, little mountains. That fascinates me.”

A silver spoon by Haida carver Charles Edenshaw (1839-1820). The bracelet of one of five Edenshaw works being donated by art dealer Donald Ellis to the Vancouver Art Gallery. Ian Lefebvre/Vancouver Art Gallery

Ellis is one of the world’s top dealers in Indigenous art. Many people recognize him from the American version of the Antiques Roadshow, where he did a famous appraisal of a Navajo blanket for $350,000 to $500,000. The old guy who brought it in starts to tear up, and it became one of the most famous appraisals in the show’s history.

Originally from Ontario, Ellis moved to New York when his business took off. But he now spends most of his time in B.C.

“It’s my adopted home,” said Ellis. “I’ve been living in New York and Vancouver, primarily in Vancouver now for the last eight years. I have a modernist house on the water (on the North Shore). It changed my life. I sort of don’t ever want to be anywhere else now.”

At 62, Ellis said he’s entering a new phase in his career. He wants to semi-retire from being an art and antiques dealer and plans to work with public museums to build their collections.

This includes the VAG, where he will be making a “significant” donation for the proposed new Vancouver Art Gallery at Larwill Park downtown.

He said part of his inspiration was the legacy of artist Gordon Smith, who died this week at the age of 100.

“You could probably argue the reason I’m doing this now with the VAG is rooted in Gordon,” said Ellis. “One of the many things Gordon taught me through observation is the value of generosity. Gordon was the most generous human beings I’ve ever encountered.”

In recent years, Smith was known for giving visitors to his home a work for art as a gift.

“It got to the point where it was difficult to visit,” Ellis said. “I think 98 per cent of the times I visited Gordon, I left with a gift.”

Charles Edenshaw at work in Massett, Haida Gwaii.

https://vancouversun.com/feed/