For Indigenous Authors, Cutting Shakespeare from Class Is About Balance

Credit to Author: Anya Zoledziowski| Date: Thu, 23 Jan 2020 11:00:00 +0000

Ottawa Catholic School Board is revitalizing its Grade 11 English curriculum by swapping out the old reading list—saturated with white authors like Shakespeare, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Margaret Atwood—with Indigenous literature from Sheila Watt-Cloutier, Tanya Talaga, Drew Hayden Taylor, and Richard Wagamese.

The new offering, “English: Understanding Contemporary First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Voices,” will be implemented across the school board over the next two years, the Ottawa Citizen reported, with the initiative launched in five schools already.

Books include Talaga’s Seven Fallen Feathers, which investigates the deaths of seven Indigenous youth in northern Ontario and uncovers ongoing human rights violations against Indigenous communities, and Wagamese’s Indian Horse, which details the systemic abuse Indigenous students experienced in Canada’s residential schools.

Ottawa’s Catholic board is following other school boards that have already started shaking up Grade 11 English elsewhere, including Windsor, Ontario. The reading lists challenge harmful Indigenous stereotypes often found in media and teach Canadian histories—the residential school system, and the forced removal of Indigenous kids from their homes into foster care during the Sixties Scoop, for instance—that have been historically overlooked in classrooms.

The push to introduce kids to Indigenous writing is in line with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action, which recommend a mandatory “age-appropriate curriculum on residential schools, Treaties, and Aboriginal peoples’ historical and contemporary contributions to Canada” for students in Kindergarten through Grade 12. VICE spoke to four Indigenous writers to hear what they think about the overhaul.

'You’re conditioning a whole generation of people to only understand one voice'

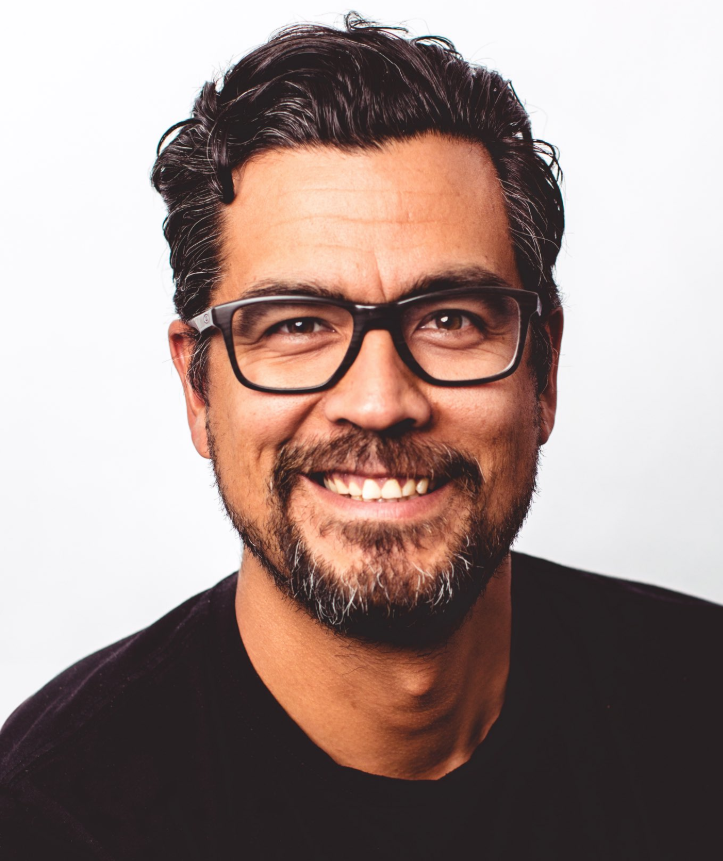

Waubgeshig Rice, Moon of the Crusted Snow, Wasauksing First Nation, Ontario

It’s a great sign when school boards are willing to take the initiative to include a wider array of voices. It wasn’t like that at all when I was in high school; I was exposed to Indigenous literature outside of the classroom. An aunt of mine who was a teacher recognized I was into English and creative writing. She gave me Thomas King and Richard Wagamese. I was fortunate that she showed me some of that great work that was happening, otherwise I wouldn’t have known. When I talk to other people who were in Ontario in the ‘90s, we all basically read the same books. Think about it: you’re conditioning a whole generation of people to only understand one voice. It’s great that kids nowadays are seeing a more diverse reading list.

'I felt like an initiative instead of a person'

Terese Mailhot, Heart Berries: A Memoir, Seabird Island Band, British Columbia

It’s important to try to understand or look at something through an Indigenous lens. It’s also important to showcase a craft perspective, like how Indigenous literature can teach writers about scene, story, and setting. The school board is minimal in its efforts, especially if it’s a specified, compartmentalized, finite amount of time during which you’ll be exposed to an Indigenous lens.

We also have to craft lessons to the sensibilities of a young person. I have a son who is 14 and I understand the power of exposing him to a Native author in his own curriculum—he’d be really happy with that. He’s currently reading typical texts like To Kill a Mockingbird. These are dated books that are supposed to teach you something about race. If my son were to read something like Indian Horse, he would feel represented and he’d learn something about Canadian Indigenous history.

These across-the-board measures remind me of when I was at school and teachers would say we have to tolerate each other. I felt like an initiative instead of a person. We can always do more.

'Let’s have a balanced curriculum that includes Indigenous voices'

David Robertson, The Evolution of Alice, Norway House Cree Nation, Manitoba

It strikes me as odd that we are replacing literature at a Grade 11 level with Indigenous literature, but we are presumably leaving the curriculum as it is in Grades 9, 10, and 12. There’s value in integrating Indigenous literature into the curriculum at all levels. I’m not saying let’s replace all literature, but let’s have a balanced curriculum that includes Indigenous voices in all grades.

But I know enough teachers to know they are trying their best. Any movement towards integrating Indigenous literature into the curriculum is positive, considering these things were never taught as early as 15 to 20 years ago. A school board reaches a number of future leaders—children—and can expose them to literature that teaches about Indigenous peoples and history and values. Schools really need to take that seriously. We all have our roles and in the end, what we need to be doing is listening to stories, sharing out stories, and seeing each other in stories.

It’s a really good time to be in this country because we have so many people telling important stories and they’re all at our fingertips. Richard Van Camp, Eden Robinson, Waubgeshig Rice, Katherena Vermette—I’ve left out a bunch of people and they’re all amazing.

'See what First Nation schools in your district are doing'

Trevor Jang, freelance feature writer, Wet'suwet'en Nation, British Columbia

Having more mandatory Indigenous literature in the school system is important for two main reasons: educate non-Indigenous youth about the history of colonization and how those impacts are still lingering, and for Indigenous youth to see themselves represented in curriculum, particularly in the mainstream system.

When I was growing up, I always knew that I was First Nations, but I never understood what that means largely due to the residential school system and the Sixties Scoop. My mom was Indigenous and she never got the opportunity to be immersed in culture, so she never got to pass that onto me. I never got to learn about that in school or in English class, and it wasn’t until I became an adult that I began to discover what being Indigenous means. If I was forced by a teacher to read Indigenous literature, it might have opened up my pursuit into my identity a lot sooner.

Regarding best practice, you have to engage local nations within districts. Most school districts have some sort of Indigenous education specialist or manager or principal, so engage with local nations. They’ll have committees of elders and curriculum material for on-reserve schools. See what First Nation schools in your district are doing and engage them.

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Follow Anya Zoledziowski on Twitter.