Photos of the First Known Collection of Webcam Covers

Credit to Author: Elizabeth Renstrom| Date: Mon, 23 Dec 2019 13:28:58 +0000

Jason Lazarus is a Florida-based multimedia artist exploring themes of vision and visibility. We've previously featured his notable archival project "Photos That Are Too Hard to Keep," where people anonymously mailed images they could no longer hold onto from across the country. His latest project explores a different kind of archive—specifically of used webcam covers. Yes, that bedraggled little quarter of a Post-it Note or piece of Scotch tape can now have an official home should you want to send it to the address provided by Jason at the end of this article.

In return, Lazarus sends artist-made webcam covers as a thank you to participants—more info at his website. He's already received countless donations from around the world and we decided to catch up with him on the purpose of this project and his compulsion to collect.

VICE: Many of your projects end up becoming archives as art, most notably for VICE readers I immediately think of "Photos That Are Too Hard to Keep." What compels you to collect? How did you start tying it into your practice as an artist?

Jason Lazarus: I think it’s a form of love—a belief that these everyday materials radiate greater possibilities of bearing witness and present/future meanings—that generates the compulsion to collect. Collecting is also a necessary counterpoint to my other forms of making which, initially, was to always to pick up a camera, control it, and execute an image. After making many images from 2003-2008, I wanted to say less and listen more, to introduce more chance and discovery in my practice and in the way I navigate the world.

My first collection, around 2006, was for my project Nirvana, which asked, "Who introduced you to the band Nirvana?" and, "Can you share a photo of this person from around the time period when they made this introduction?" The project started very organically—my friend Lindsey was showing me a photo album and went into great detail about a snapshot of "Josh," her older brother's friend who she was infatuated with and who introduced her to Nirvana.

The photo was poorly focused, had a powerful glare behind the subject, was cropped awkwardly, with aging/exaggerated color—it was perfect! It was everything I had been trained not to do in my photography education and Josh was clearly an icon for young Lindsey. I realized this was the seed of a project and started to collect around this idea, with the growing awareness that the project was not only about the band, but about these pre-internet culture-carriers that come into our lives and powerfully recalibrate young identities and fantasies.

Nirvana opened the door for many other growing archive projects: THTK, Recordings, Orion Over Baghdad, Phase 1 Live Archive, A Century of Dissent: Miami—these are all viewable at my website. Each of these projects build and complicate each other, I hope, and implicate the other sculptures, photographs, collections, and installations I create.

Artist collections are critical and necessary—artists are uniquely situated to create powerful, idiosyncratic collections because their research is often non-linear, far-ranging, and multi-disciplinary; artists can see and make connections others miss. I think all young artists should explore collections as a (cheap!) meaning-making exercise in their everyday lives.

My friend and artist Sue Havens just introduced me to Claes Oldenberg’s Ray Gun Collection comprised of items merely shaped like ray guns which he collected from everyday walks—friends soon started bringing ray gun-shaped items to him as well. I think about this collection now daily. One more recommendation, Liene Bosquê (Miami/NYC) also expands ideas of collecting in many fascinating directions, her website is a treasure of collections mixed in with other sculptures, installations, and social-engaged actions.

With this in mind, what made you want to create the first known archive of webcam covers?

A cloud of things, I think. Early this year, I was staring at my laptop's beat-up webcam cover while laying in bed—the white tape had folded and wrinkled a number of times, and even had, I think, a coffee stain on it. It was such a small sculptural wonder to me that I thought about capturing and enlarging it (either as a photo or sculpture) just to further explore it as a complicated form.

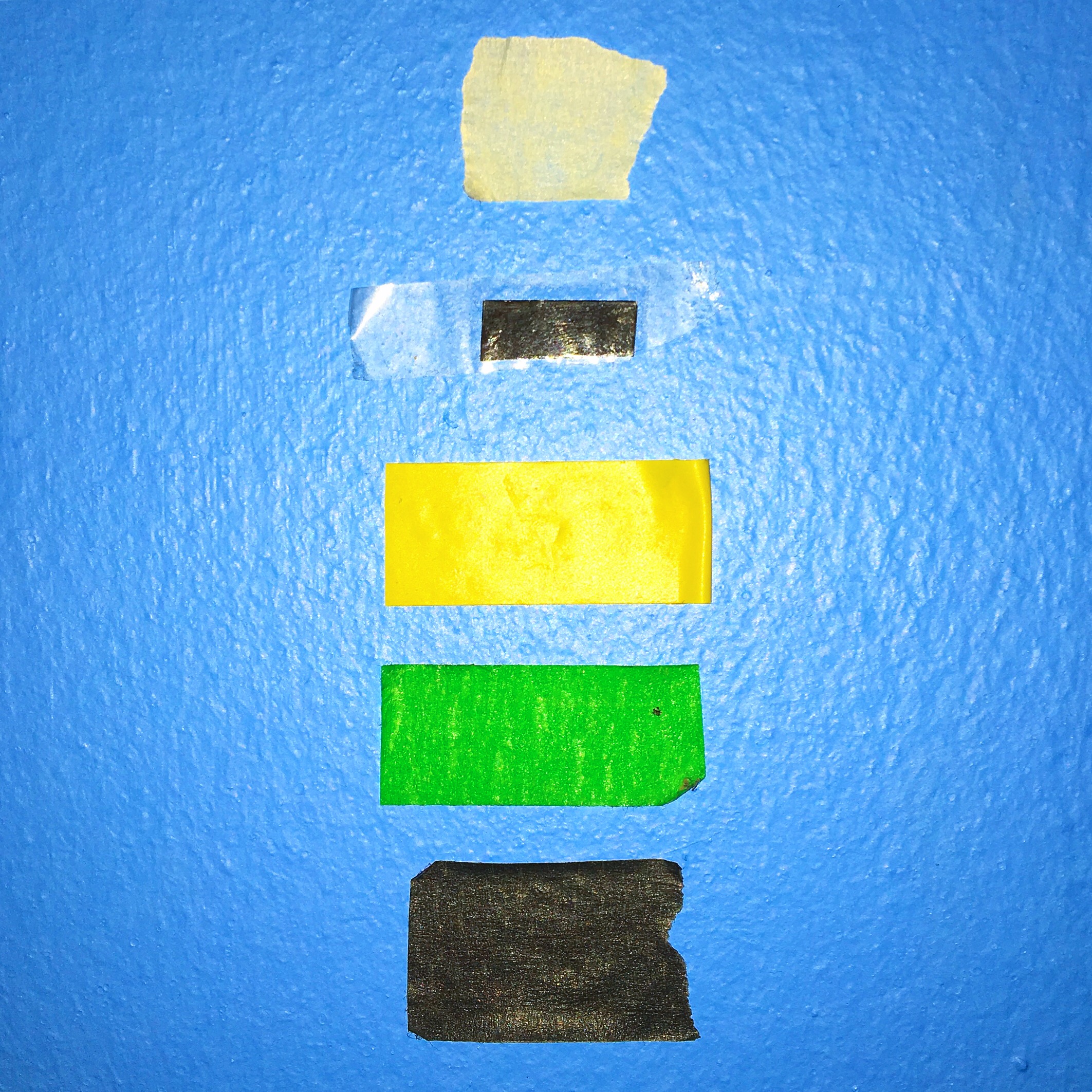

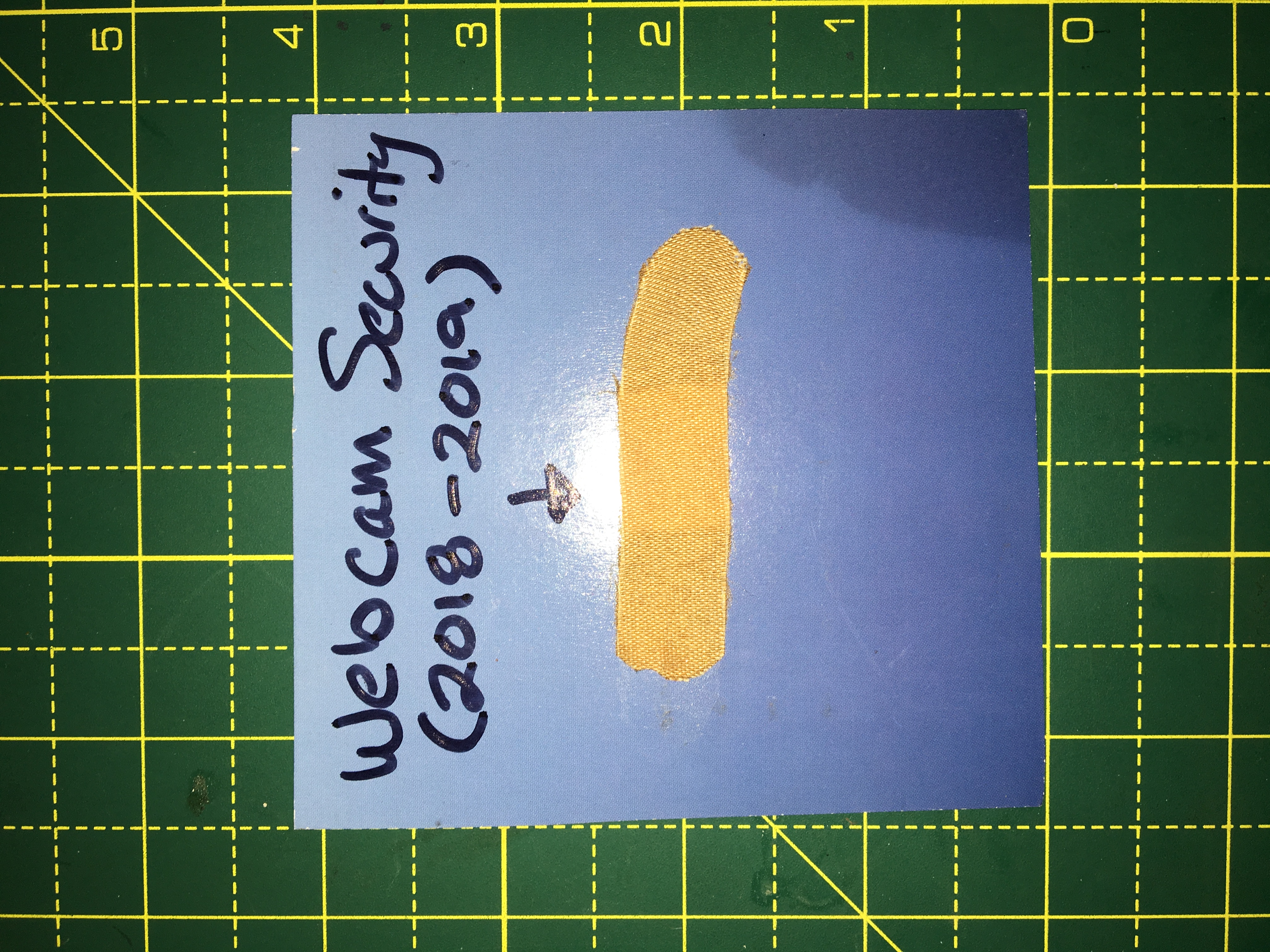

But its implications, context, and the variety of others I saw in my everyday life started to pull me toward collecting used originals. Our webcams are in such an intimate space, staring at us unblinking, as a sort of default open aperture for most people. You have to make a choice to close it, and this choice is represented by the most modest, casual means, often in relief against the sleek design of our computers—it’s a fantastic clash and the covers became analogous to me of a protest sign (I think of them as the world’s smallest protest signs) or a gate, a Band-aid (sometimes literally), a panopticon, etc.

Years earlier, in 2010, I had read about the tragic suicide of Tyler Clementi at Rutgers University, spurned by being outed through webcam spying by his roommate, which made such a strong impression on me. Last, in the past few years, I’ve been thinking more about objects that are about images—a kind of 'metadata,'—objects that are about images, vision, and visibility. And last, the 2016 New York Times article Mark Zuckerberg Covers His Laptop Camera. You Should Consider It, Too that features an incidental view of his webcam cover lingering in the lower left-hand corner of a tweeted office image.

As a thank you to those who submit to the used webcam cover project via snail mail, I send a small webcam cover I produce that is a photographic sticker—a very zoomed-in image detail (so zoomed in it’s almost abstract if you don’t know what it is) of Zuckerberg’s webcam tape cover.

Have you noticed any trends in certain locations throughout the submission process? I would gleefully be opening these envelopes, but I imagine the simple tape method is probably the majority of what you receive?

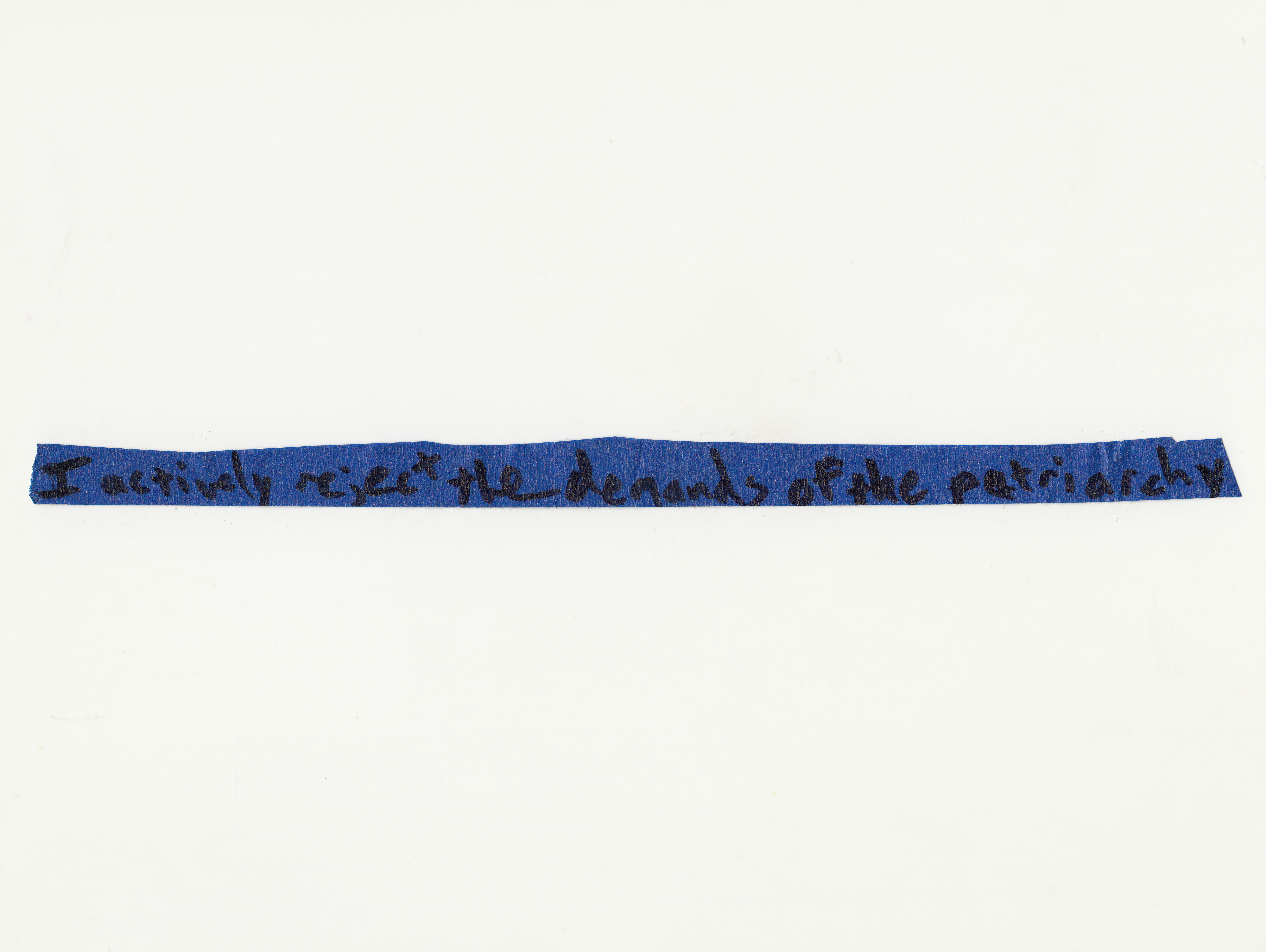

The project is still young so I’m very much a student at this moment of the submissions. I really try to stress the submissions need not be fancy or flashy, I have a high appreciation of even the most simple lengths of used tape. Some webcam tapes double as motivational signs or everyday reminders (‘turn off the heat’), others seem like a reassuring pet or companion. And on occasion the covers are overtly political (‘i actively reject the demands of the patriarchy…’). I’d estimate less than five percent of the population uses a webcam cover right now and I am very thankful to find them on the computers of friends and strangers. Most fun is making the most of my waiting time at airports, approaching strangers seated at restaurants and gates and making a pitch for the project—you follow the collection into the world…

You mention on your website that you see this as a small and popular form of resistance. I was wondering if you could speak to that a little more. I know you also worked to archive and show signs from the Occupy Movement and I’m curious how this relates to that collection.

Yes, protest imagery, histories, and strategies have become an ongoing subject for me since 2011’s Occupy Wall Street movement. Protests often involve an economy-of-protest, meaning how much time, materials, peer-support, and expertise do I have to make an impactful statement on the street with an active audience and layer of media present—protest signs are made for the street and for the camera. I’ve always found myself lingering on the protest signs that were made quickly, modestly, and in earnest, that seem to speak first person for the holder.

I think of these as potent news flashes revealing old and new cracks in the grand democratic experiment that we seem to be failing at—technology seems to offer an initial democratizing possibility for expression and exchange before surveillance states and corporatization take over. The webcam covers to me are a kind of extremely distilled object of resistance that quietly and economically manifest much larger and abstract systems of power, visibility, and control. I seem them as what they are and as kindred surrogates for many other protest objects, tactics, and movements. As an artist you have the potential to implicate or politicize everyday materials that surround your audience into their everyday life—our audiences can then carry, linger, and complicate these (fluid) meanings forward.

Do you remember when you put your first webcam cover on your monitor? What made you do it? What was it that you didn’t want seen?

The aforementioned things all led to me using a cover perhaps starting in 2018? I don’t remember doing it at first, but James Comey has a great line in the Times article I relate to:

"I saw something in the news, so I copied it,” Mr. Comey said. “I put a piece of tape — I have obviously a laptop, personal laptop — I put a piece of tape over the camera. Because I saw somebody smarter than I am had a piece of tape over their camera.”

Of course, like many, I don’t want a visual pipeline to my everyday life, we all need space that is sacred and profane.

What other measures or artifacts do you think will appear out of acts for cybersecurity?

I’m not sure, but the artifacts they are increasingly invisible—we will have to work harder to understand the multiple, nefarious grids that ensnare us.

What is next for this project? How would you want to showcase and who are you hoping to reach with this work?

This project is in the growth stage currently, and like many of my projects, I see it as a kind of mobile, public monument with a wide and varied audience—for a start, take a look at the next computer user you see!

You can follow more of Jason's work here. To submit to this project and receive an artist-created webcam cover as a thank you, send your used cover to:

Jason Lazarus

212 w Thomas St.

Tampa, FL 33604

To request a prepaid envelope for mailing your webcam cover, email Jason at jasonlazarus.com@gmail.com.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.