Exclusive: B.C. jail guard accused of sexually abusing 200 young inmates

Credit to Author: Lori Culbert| Date: Sat, 23 Nov 2019 01:19:47 +0000

Just a couple of years into Roderic David MacDougall’s two-decade career as a provincial corrections officer, co-workers began to raise concerns with Oakalla prison managers that young inmates were being sexually abused.

The other guards noticed a worrisome pattern: Every time MacDougall, who controlled whether inmates got temporary absences and other perks, spoke to older inmates in his office, it took just a few minutes. When teenage inmates were behind his closed door, the sessions appeared to last much longer, about 45 minutes.

“While we had no facts to go along, people took it upon themselves to report it to management, express their concerns that this is unusual,” Kenny Johns, a former guard, testified in a 2018 civil trial.

Johns, who had worked in other jails, became concerned about MacDougall shortly after he was transferred in 1978 to Oakalla’s Westgate B wing. He and his co-workers used watches to time inmates’ closed-door meetings with MacDougall, who had started working for B.C. Corrections just two years earlier.

A colleague told two senior managers the guards were worried the young inmates were potentially being sexually abused, Johns testified, but he is not aware of their complaints being addressed.

“I was never informed of any investigation,” Johns testified in the 2018 case, in which a man successfully sued the province over being gang raped by inmates in Oakalla when he was 14 years old in the late 1970s. (In that case, Justice Jennifer Duncan ordered the province to pay the victim $175,000 but dismissed the claim against MacDougall, concluding the evidence did not prove the allegation that his conduct allowed the rape to happen.)

The report to management described in Johns’s evidence was the first of many warning signs over two decades, a large collection of court documents allege. These ranged from a guard submitting formal memos outlining concerns about MacDougall to frustrated co-workers resorting to vigilante justice — such as removing the door from his office and sending emails to staff from MacDougall’s own computer that claimed he was abusing young inmates.

An undated photo of Roderic MacDougall taken before 2005.

Today, more than 200 former inmates have filed civil claims in court alleging they were sexually abused by MacDougall over his 21-year career when they were teenagers or young men incarcerated for relatively minor crimes. The plaintiffs claim the attacks left them angry and confused, often compounding pre-existing drug and crime problems, and spiralling them into even more difficult lives.

MacDougall, a long-time government employee, is described as “one of Canada’s most prolific sexual offenders, with more than 200 former inmates who have already come forward” in a lawsuit filed last month on behalf of 61 men with outstanding civil claims.

“The telling of (MacDougall’s story) is long overdue,” said Megan Ellis, a Vancouver lawyer who has represented survivors of sexual abuse for more than 25 years, including at least 10 of MacDougall’s alleged victims. “It is a shameful blot on the history of this province and the responsibility of the provincial government.”

In defences filed in some of the more recent civil claims, the provincial government denies “it knew or ought to have known” inmates were being sexually assaulted during MacDougall’s career, which spanned 1976 to 1997. The defences also denied MacDougall sexually assaulted the plaintiffs, or that its corrections system did anything wrong.

In the 2018 gang rape case, MacDougall did not file a defence or participate in the trial, which has been true for most of the recent civil suits filed against him.

However, he did file a defence statement in a 2001 civil case that accused him of abusing a prisoner, in which he pleaded, “I deny all accusations by (the plaintiff) …. They are untrue.” The plaintiff in that case was originally awarded $20,000 after the judge found he had been assaulted while an inmate in 1986 and 1995. The Court of Appeal ordered a new trial, after the plaintiff argued the payment was too low, but the new trial never happened.

MacDougall, now 66, declined to comment on the civil suits or any of the allegations against him when Postmedia contacted him at his Lower Mainland home.

He maintained his innocence, though, at a 2000 criminal trial, at which he was convicted of sexual assault, indecent assault and extortion in relation to five inmates, all of them 17 or 18 years old, in the 1980s.

About half of the 200 civil suits are now completed: Some resulted in payouts totalling, by conservative estimates, at least $500,000 by the provincial government, which as MacDougall’s former employer admitted indirect liability for his actions; an undisclosed additional amount of money has been paid out for some private, out-of-court settlements; and a few cases were dismissed because the trial jude found the allegations hadn’t been proven.

The other half of the civil suits remain ensnared in a long, complicated legal process that has pitted the plaintiffs against the legal weight of the provincial government, which is a co-respondent in most of the remaining cases. The allegations in these outstanding cases remain unproven.

The most recent lawsuit, filed last month, is a “representative action” — similar to a class-action lawsuit — and must still be approved by a judge. It goes a step further than the previous ones. It argues the province was more than a secondary player: that through its own “systemic misconduct,” it failed to respond to the many complaints about its employee and therefore “facilitated the sexual assaults.”

“The sexual assaults have had devastating emotional and psychological impacts on the victims,” alleges the representative action filed by lawyer Karim Ramji. The province and MacDougall have not yet filed statements of defence to the allegations, which remain unproven.

Surrey resident Errol Johnson is trying to overcome a heroin addiction, a habit that intensified, he alleges in a lawsuit, after he was sexually abused in Oakalla, the infamous Burnaby jail, in 1986 and 1987.

Johnson sued MacDougall and the province in 2014 but that case has not yet gone to trial. He is now a pending plaintiff in the representative action, and wants the government to be held accountable — and wants society to know how the alleged victims, and their families, have suffered.

“We’re people, too. We have addiction issues, or other issues, but we’re people and we don’t deserve what happened to us,” Johnson told Postmedia. “That was not the sentence. The sentence was you’re sentenced to two years, or six months, and that’s what it is. You don’t deserve sexual abuse while you’re in there too. … Guys have died without any justice at all. And nobody cares.”

Errol Johnson in Vancouver. Arlen Redekop / PNG

So, how is it possible that as many as 200 inmates could complain of sexual assault in provincial jails over a span of 20 years without officials stepping in earlier? And has the system changed sufficiently today to assure British Columbians that history won’t repeat itself?

Jennifer Metcalfe.

“I think B.C. Corrections is better run today, but much more needs to be done to prevent sexual violence in B.C. prisons,” said Jennifer Metcalfe, executive director of the legal-aid clinic Prisoners’ Legal Services, which helped provincial prisoners with 1,404 issues of varying descriptions in the last year. “The power imbalance between correctional officers and prisoners is extreme.”

MacDougall quit his job in 1997 following a scathing review that was sparked not by sexual abuse concerns, but by his own complaint that he was being bullied by his co-workers.

A year later, he was charged with 17 criminal counts. His first trial ended in a hung jury in 1999. The next year he was convicted of nine of those counts.

While sentencing MacDougall in November 2000, B.C. Supreme Court Justice Mary Ellen Boyd said the young victims were all small in stature and had no experience in the adult prison system, while MacDougall had “extensive power” over parole applications or prison transfers, which he offered in exchange for sexual favours. If the inmates declined his demands, he would threaten to make their lives far more difficult behind bars, Boyd’s reasons for sentencing said.

“They were all vulnerable boys, and I use the word ‘boy’ deliberately, clearly overwhelmed by the circumstances in which they found themselves,” wrote Boyd. “In every case, the sexual act or acts occurred with each complainant believing that his future physical security within the prison system depended on his co-operation.”

In her reasons for sentencing, Boyd said MacDougall’s lawyer explained that his client was raised in an era with little tolerance for homosexuality and had never come to terms with his sexual orientation. Therefore, Boyd wrote, MacDougall in his “deep frustration … took advantage of these young inmates.”

MacDougall was hard-working and there were many inmates who said he helped them, Boyd wrote, but he appeared incapable of accepting responsibility for the offences for which he had been convicted. For his personal safety, she sentenced him to two years of house arrest, saying he would be a pariah in jail, hated by both inmates and guards.

The Crown appealed MacDougall’s sentence, and the B.C. Court of Appeal increased it to a four-year custodial sentence, minus time served.

“The accused was a predator who must have understood that he was abusing both the authority of his position as well as the minds and bodies of his victims,” then-Appeal Court Chief Justice Allan McEachern wrote in the 2001 unanimous decision.

No new criminal charges have been laid against MacDougall since the 2000 trial, although the RCMP recommended additional charges in 2002 that were declined by outside legal counsel, a special prosecutor hired by the province, the representative action lawsuit says.

After more alleged victims came forward in 2006, the representative action alleges, the deputy regional crown counsel asked the RCMP to investigate again. The three-year police probe ended in 2010 with the RCMP recommending additional criminal charges on behalf of 13 alleged victims.

This time, the province did not hire a special prosecutor and, after the RCMP report was under review for three years, the proposed charges were not approved. (Charges in B.C. are based on the standard criteria of whether there is a substantial likelihood of conviction and whether the prosecution is in the public interest.)

“A special prosecutor was not appointed in this case,” Dan McLaughlin, spokesman for the B.C. Prosecution Service (BCPS), said in an email. “The decision was made not to approve criminal charges against the accused. The charge assessment decision was made by a senior prosecutor with the BCPS.”

Postmedia requested an interview with Attorney General David Eby, who was not in government when this decision was made, to discuss why a special prosecutor would not have been hired when the man accused was a former government employee and the province was a co-defendant with him in civil lawsuits. Eby said in a statement that it would be inappropriate for him to comment on the special prosecutor decision or the new representative action lawsuit.

Metcalfe’s legal aid group says allegations of sex assaults are still being made by those incarcerated in B.C. jails.

“I would like to see more independent external oversight of B.C. Corrections, with more transparency in the form of public reporting of staff misconduct,” said Metcalfe.

After Ombudsperson Jay Chalke released a critical report in 2016 on a lack of inspections in B.C. jails, the province acted on all but one of his recommendations: It missed a self-imposed March 2018 deadline to implement international “Nelson Mandela rules” to have external oversight of what happens inside jails.

“I’m very disappointed. Three and a half years after we issued our report, and a year and a half after the government agreed to have these three Mandela rules in place, we still don’t see any implementation,” Chalke said.

“Recently the government advised my office that they are working on a new plan, which they intend to have developed early in the new year to implement those rules. This is some cause for optimism, but it follows an unacceptable delay.”

Solicitor General Mike Farnworth, whose ministry oversees jails, was not available for an interview, but in a statement said his government is close to implementing Chalke’s recommendation.

B.C. Ombudsperson Jay Chalke.

Farnworth’s statement also said that there are now more cameras in jails to increase safety; there is a complaint process for inmates with concerns; all staff misconduct is investigated and reports are immediately made to police when a crime is alleged; and over the last six years, B.C. Corrections conducted more than 100 internal inspections and found no “safety or security concerns” inside jails.

But new lawsuits against a second former Corrections officer allege problems existed in at least one other B.C. jail.

In civil suits filed last month, three men allege that they were abused by then jail guard Christian Hauer between 2003 and 2011, when they ranged in age from 13 to 17, in the Victoria Youth Custody Centre. Their allegations have not been proven in court.

In an email to Postmedia, Hauer, who retired from the corrections service in 2011, strongly maintained his innocence, and according to Court Services Online he has never been charged criminally. He has not yet filed a statement of defence to the three civil cases.

“None of the allegations are true and totally made up,” Hauer’s email said. “The claim that management at the custody centre were negligent and failed to protect its residents (inmates) couldn’t be further from the truth. Rules and regulations guiding the conduct of employees were quite extensive and always enforced.”

Youth jails are overseen by the Ministry for Children and Families, which would not discuss this case because it is before the courts. It provided Postmedia with its Standards of Conduct policy, which prohibits “inappropriate relationships” between jail staff and the youth.

The lawsuits against MacDougall and Hauer, both filed by Vancouver lawyer Ramji, demand systemic changes to the correctional system.

“The sexual assault of inmates is a well-known phenomenon occurring within jails,” the court filings against Hauer claim, noting these types of problems were highlighted in the 1978 Royal Commission of Inquiry probing sexual misconduct between guards and female inmates at Oakalla.

“The province is also directly liable … as a result of its negligence, breach of fiduciary duty and misconduct in failing to properly investigate allegations, rumours and knowledge of the sexual assaults,” the court documents in the Hauer suit allege.

MCFD has not yet filed a statement of defence in the Hauer suits.

However, in response to recent, still-unproven civil suits filed against MacDougall, the Solicitor General’s Ministry insisted it “exercised reasonable care in the hiring and supervision” of MacDougall, and appears to blame the plaintiffs for not taking steps to mitigate damages from the alleged abuse, such as “fail(ing) to seek treatment.” This argument was made as part of the government’s 2018 response to one of those suits, filed by a man who alleges he was forced to submit to oral sex and was digitally penetrated while in Oakalla between 1989 and 1990, when he was in his early 20s.

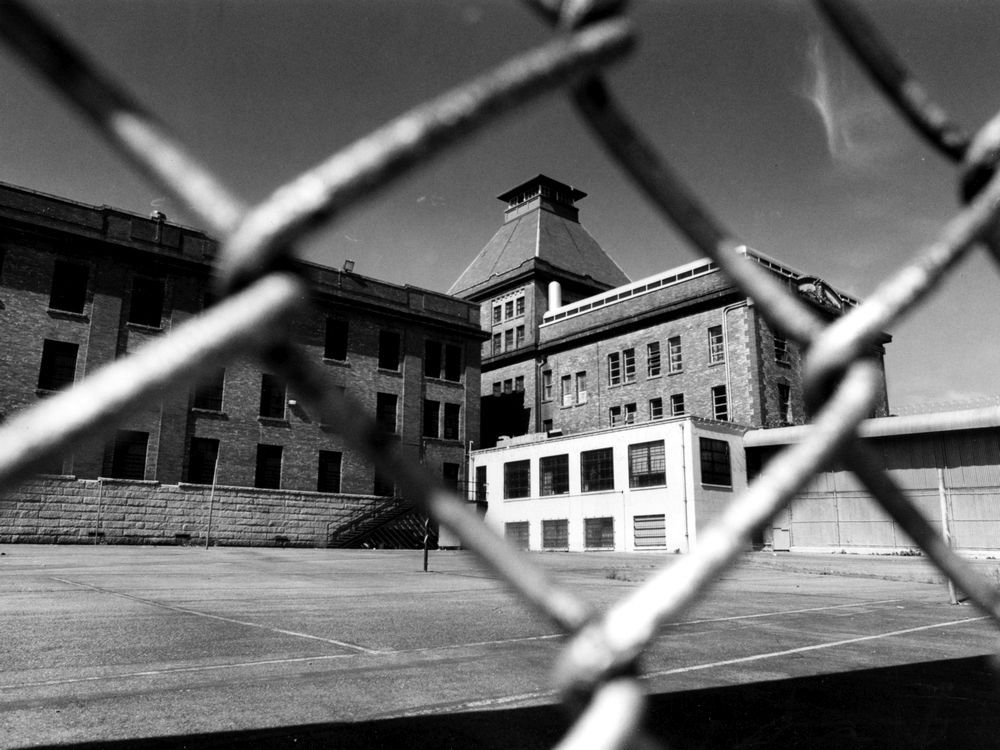

Oakalla prisoners in 1975.

Former guard Robert Prins, who worked with MacDougall, has heard from former co-workers that some systemic problems still exist in jails today.

“You can’t fix what happened 30 years ago. … (But) what’s going on now? What’s being overlooked now and what’s being swept under the carpet now? And what’s the damage?” asked Prins, who was a B.C. jail guard for 15 years.

“At the end of the day, somebody’s got to get up off their butt and say: ‘You know what? This is unacceptable, for any number of reasons.’ And the only way we can address it is to appoint an independent overseeing body — truly independent — with the power to do more than just make recommendations.”

Today we explore allegations about what happened in Oakalla, Alouette and other facilities where MacDougall worked years ago, based on hundreds of pages of court documents, including lawsuits, judges’ rulings, testimony transcripts and expert reports. Over the next three days we will look at the impact of those allegations, the long legal battle, and what still needs to be changed in the system.

Roderic David MacDougall had worked at Simpson Sears and on Annacis Island when, in January 1976 at age 23, he had a job interview with B.C. Corrections. He started work at the Lower Mainland Regional Correctional Centre, known as Oakalla, the same day.

That year, Justice Patricia Proudfoot launched her royal commission into allegations of misconduct between male guards and female inmates at Oakalla Women’s Correctional Centre. Proudfoot released recommendations for change in 1978, around the same time that guard Kenny Johns and others began raising alarms about MacDougall on the men’s side of the jail.

Justice Patricia Proudfoot in 1978.

Around 1982, Corrections officer Frank Boshard was approached by a young inmate who he was watching over because their fathers were friends. The inmate alleged MacDougall had made sexual advances toward him, Boshard said in sworn evidence that was filed with the court in a 2018 civil case brought by three former inmates against MacDougall and the province.

In his testimony, Boshard said he confronted MacDougall, telling him to leave the inmates alone, and then typed his concerns on a “provincial memorandum” form that he submitted to management.

“It fell on deaf ears,” he said in his deposition, which has not been tested in court because the civil case has been paused while the plaintiffs added their names to the representative action lawsuit.

Boshard claimed that over the next two years MacDougall was twice promoted by those who had received his memo. “(They) knew about it (the alleged abuse) and they promoted him,” he alleged.

Postmedia could not interview Boshard, who recently died, but former guard Prins worked with Boshard and can remember him raising concerns with management. “Direct complaints were made by people like Frank Boshard and Kenny Johns,” Prins said.

Prins recalled that Boshard was “frustrated and angry.” And it appears he was not alone.

One night, when Boshard was the shift supervisor, six guards told him they wanted to replace the solid-wood door on MacDougall’s office with one that had a window so they could see what was happening inside, he said in his evidence.

“They wanted a window into MacDougall’s place because MacDougall never left his door open. He always shut it,” Boshard said in his deposition.

The guards brought the door from the prison’s carpenter shop and installed it that night, Boshard recalled, but within days MacDougall had covered the window.

“He put a file thing over it and then he had little curtains made,” Boshard testified.

At least two guards confronted MacDougall about the window coverings. Jim Reilly, a long-time Corrections employee who rose to assistant deputy warden at Oakalla, provided evidence on behalf of the province at the same civil case in 2018, and recounted former guard Bob Milne “taking (it) down and destroying the curtain.”

MacDougall also agreed to be deposed in 2018 for the same civil suit, and recalled replacing the curtain once and then giving up.

“I can remember it being ripped off twice,” MacDougall said. “(The co-worker) said, ‘I don’t want you to have that on there.’ … He came in and just ripped it down. And I went, ‘OK.’ It was as simple as that.”

An Oakalla cell in 1972

Roughly four years after the door incident, 16-year-old Oakalla inmate John Smith — Postmedia is using a pseudonym to protect his identity because he was an alleged teenage victim of sexual assault — asked MacDougall for a day pass so he could visit his grandmother.

“Mr. MacDougall made his terms clear: Mr. (Smith) could get a day pass but only on condition that he submit to fellatio performed by Mr. MacDougall,” B.C. Supreme Court Justice G. Peter Fraser wrote in his 2006 civil case ruling, in which he found the Crown had admitted MacDougall sexually assaulted Smith and ordered the province to pay $20,000 in damages. “Mr. MacDougall drove him to visit his grandmother on the day of the pass. On the way there they parked and the act of fellatio took place.”

Some time later, Fraser wrote, MacDougall encouraged Smith to apply for parole, despite his criminal record, drug use and violent behaviour in prison. “Mr. MacDougall suggested that he could influence the outcome of the parole decision,” Fraser wrote. “The price extracted by Mr. MacDougall was fellatio.”

Smith’s lawyers appealed the $20,000 payment, arguing it was too low. The B.C. Court of Appeal agreed that Fraser did not take certain evidence into consideration when determining the amount of damages to which Smith was entitled and ordered a new trial, but it never took place.

At this time in prisons, there was a strict code that no one should “rat” on anybody, which MacDougall used to his advantage, Boyd wrote in the 2000 criminal judgment.

Justice Mary Ellen Boyd in 2001.

“Any reporting of the events to the authorities would likely be fruitless since, as the accused reminded them, a prisoner’s word meant nothing against that of a guard. Any reporting of the events to a fellow inmate would even be worse. The inmate would be branded as a guard intimate, a rat, or a homosexual, all brands within the prison which were threats to one’s physical security,” Boyd wrote.

None of the five victims in the criminal case initially told anyone about the abuse, Boyd said, which included being forced into oral sex and/or mutual masturbation, and in a few cases anal penetration. The victims testified that If they refused MacDougall’s demands, he threatened to arrange for other prisoners, who “would not be as nice about it,” to rape them, Boyd wrote.

Before Oakalla closed in 1991, MacDougall was transferred to the Fraser Regional Correctional Centre, where he infuriated his co-workers by telling managers he saw two fellow guards beat up an inmate, and by spearheading an investigation into whether guards were bringing drugs into the jail. He was the target of a harassment campaign that included obscene phone calls to his home, multiple tire slashings, posting of vicious cartoons, an assault, and a dead rat delivered to his office in a box, documents say.

After this, MacDougall was transferred in 1993 to the Surrey Justice Centre Probation office, where he was disciplined for twice socializing with a former inmate outside work hours, according to a 1997 report that was commissioned by the province to investigate MacDougall’s claims he was being bullied by co-workers. “MacDougall had been earlier warned respecting off duty personal contacts with ex-inmates,” wrote retired Delta police chief Patrick Wilson, who was hired by B.C. Corrections in 1997 to investigate MacDougall’s claims of harassment.

Delta police chief Pat Wilson in 1994, shortly before his retirement after eight years with the municipality and another 33 years with the RCMP.

Wilson’s report was filed in Johnson’s civil case, which has yet to be tried in court because he has now joined the representative action. In the Johnson case, the province denies any wrongdoing, saying: “The province says MacDougall’s supervisors neither knew nor had reason to believe that he was sexually abusing inmates and that reasonable and appropriate measures were taken to supervise MacDougall.”

MacDougall was suspended for two days following the incidents at the probation centre, but was allowed to resume his job as a probation interviewer, Wilson wrote. He held this post for only four months before being transferred again — this time to the Alouette River Correctional Facility, where harassment by the other guards continued.

In 1994, someone sent emails from MacDougall’s own computer to everyone on his mailing list saying he was “screwing young boys” and that it was something he “had been doing for a long time,” Wilson wrote in his report, which was filed as evidence in Johnson’s civil case.

Two years later, Wilson wrote, MacDougall was suspended again for giving what he called a “comic report” to a young inmate — a two-page typed questionnaire entitled “Application For A Piece of Ass,” which asked a series of lewd questions about body parts and sex. MacDougall claimed he was not trying to harass the inmate and was just acting “in jest.” Again, he was allowed to return to his job.

John Smith, who has alleged he was abused by MacDougall in Oakalla in 1986 when he was 16, was incarcerated in Alouette in 1995 when he wanted a day pass — and the guard in charge of granting passes was MacDougall. His temporary leave was granted in exchange for fellatio, Fraser, the trial judge, wrote in the 2006 ruling of Smith’s civil suit.

Smith had obeyed the “con code” all those years in and out of jail — the unspoken rule that you don’t rat on anyone else in prison. But one day in Alouette in 1996, Smith had the courage to break this rule and “blew the whistle on this guy,” his former lawyer Ellis said.

Smith testified at his civil trial that he became concerned when he saw MacDougall call “young kids” to his office. “And I just know by the look in their eyes what was going on. I just know. They had the same look that I had when I was that age,” according to a factum filed by Ellis with the Court of Appeal.

Wilson’s report confirms that Smith told a Corrections officer at Alouette that he had allegedly been sexually abused several times. MacDougall was suspended during the investigation into Smith’s complaints, but successfully appealed his suspension, collected his back pay and had Smith’s complaint removed from his personnel file, according to Wilson’s report.

In MacDougall’s February 1997 complaint to supervisors that he was being harassed by his co-workers — the complaint that Wilson was hired to investigate — he wrote that he was devastated by Smith’s claims and shocked that management believed them.

“I want my name and reputation repaired, simple as that. I did nothing wrong, nor am I ashamed of anything I have done,” MacDougall wrote in his 17-page complaint, which was filed with the court as part of the evidence in Johnson’s civil case.

After investigating, Wilson agreed MacDougall was bullied, but determined he caused the harassment to occur. “MacDougall should not be deployed to work in direct contact with inmates,” Wilson concluded in his June 1997 report.

MacDougall resigned the day after Wilson filed his report. “It was nice while it lasted,” he wrote in his resignation letter. “It is unfortunate that no one was concerned about my welfare or well being.”

The criminal charges against MacDougall were not laid until two years later. That investigation was sparked, in part, by Smith, one of his alleged victims, confiding in a Burnaby RCMP officer he trusted. That officer put an advertisement in a local newspaper, asking to hear from other people with concerns about a jail guard, Smith’s lawyer Ellis said.

Eventually, eight other former prisoners came forward, and MacDougall was convicted of abusing five of them.

“It’s a fair complaint that this person’s egregious behaviour over such a long time was not adequately addressed or owned up to by successive provincial governments,” Ellis said of the large number of civil cases and the lack of new criminal charges.

Ramji hopes his new representative action will provide closure for the 61 plaintiffs, as well as lead to change in the corrections system.

“This isn’t just about the legal system,” Ramji said in an interview. “It’s a human tragedy.”

— With research by Postmedia librarian Carolyn Soltau

Series box

Saturday: A jail guard, the government and 200 inmates

Monday: A failure to improve oversight

Tuesday: Life sentences of shame and fear

Wednesday: A long road through the courts

CLICK HERE to report a typo.

Is there more to this story? We’d like to hear from you about this or any other stories you think we should know about. Email vantips@postmedia.com.