Inside the New Private Club for People of Color With a 4,300-Strong Waitlist

Credit to Author: Taylor Hosking| Date: Wed, 13 Nov 2019 01:35:25 +0000

As you walk up the graffiti-lined block in East Williamsburg, Brooklyn where Ethel's Club, the first-ever private social and wellness club for people of color, is located, it's hard to tell what to expect. The club, which opened its doors to its first 150 members last Monday, has been highly anticipated, and currently has a 4,300-person waitlist. Its popularity has soared presumably off the simple premise that it's one of the first coworking and social spaces curated by young people of color for other young people of color. But the ways that status would meaningfully affect the club experience was still largely a mystery to most until this past weekend.

On first glance, it could simply seem like a colorfully decorated lounge space with artsy people of color eager to socialize. But the devil is certainly in the details. Every item in Ethel's Club has a unique backstory to it, some advertised with a meticulously planted social media handle or QR code. The furniture was chosen, designed, and even upholstered by artisans of color; the free food in the kitchen and the goods for sale highlight smaller POC-run companies. Even the books in the meditation room feature writers of color analyzing racism from a mindfulness perspective.

"The club was born out of a kind of frustration and anger that no one else had done it," 28-year-old founder Najla Austin explained. Coworking spaces like the women-focused members-only chain The Wing helped her see that it was possible to start a mainstream club that advertises specifically to one demographic. And since The Wing has struggled to rehab its relationship with women of color after mishandling a high-profile racist incident back in May, Ethel’s Club is in a good position to frame itself as a long-awaited alternative. But Austin wanted her club to be more than a POC version of The Wing or WeWork.

Austin said that the idea really started to take shape when she named the club after her grandmother, Ethel Lucas. Her house in Edison, New Jersey was a community gathering place for kids to do homework, eat, or show off a report card, while adults gossiped, braided hair, or introduced the house to a newborn baby. "Everyone had homes. They could go to their own house. But it was important for the real-life aspect to meet there," Austin said. More than anything, she wanted Ethel's Club to become a home away from home for its members who may feel disoriented in a new city, or find themselves in predominantly white spaces as they progress in their careers. The drive to create a home-like welcoming environment in a coworking space isn't exactly new, but Austin set out to find a meaningful way to apply the concept to empower and rejuvenate people of color.

Austin had never started a company from scratch before, but the club practically propelled itself into existence by popular demand. "We haven't done any marketing. It's all been us reckoning with what's come to our doorstep," she explained. Last November, she created an Instagram account for the club and posted a photo of a young Black woman with the simple caption, "the first space designed with people of color in mind." Her post instantly hit a nerve, organically generating over 2,000 likes along with a flood of direct messages from people ready to join.

"We had so many people like, 'Give me this product,'" Austin said. "I was screenshotting these responses and sending them to the couple advisors we had at the time and they were like, 'Holy shit, you might actually be onto something.'"

She didn't have a location yet, but the demand compelled her to leave her job at a real estate startup four months later to focus on the club. In just 10 months, she raised $25,000 in an early crowdfunding campaign; found high-profile investors like journalist Roxane Gay; and connected with advisors like Jessica Eggert of the women-led coworking company The Riveter. And she miraculously found one of the few real estate firms in the city that make a point of renting to relatively new businesses: The Hudson Companies Inc.

In the broader history of the city, dedicated spaces just for people of color to socialize and work have been extremely rare. During booming eras like the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and 30s, Black creatives often gathered in apartments, church basements, public libraries, and touchstones like the Harlem YMCA or the mansion home of A'Lelia Walker (daughter of Madam C.J. Walker, one of the first Black millionaires). Most of those makeshift gathering places didn't endure for later generations. A number of nightlife hubs like the Black LGBTQ Brooklyn bar Langston's have shut down in recent years, while other historic Black cultural hubs like Weeksville Heritage Center have struggled financially to stay open. And even economically secure institutions like The Apollo are fighting to stay relevant to today's young artists.

Today's creative collectives and party collectives for people of color that have grown online notoriously struggle to open their own permanent locations amid gentrification and high turnover among organizers. They most commonly hold rotating events at one of the few remaining Black-owned venues in the city or any trusted space that will have them.

When Austin started meeting with potential investors, a few asked why she wouldn't go a similar route and create her space as a pop-up. One potential investor even suggested that she rent a cheap basement room with Goodwill furniture, to which she countered, "Why do people of color always have to settle for the shortest stick ever?" She explained, "That idea of creating a very beautiful space for people of color with specific items chosen for their happiness and for them to laugh or feel seen and agree with was critically important." In some ways, the space is a referendum for all those who couldn't have it before.

Taking advantage of the historic rarity of founding a new culture hub, she brought some of the club's mission through in the interior design. Austin hired Black interior designer Shannon Maldonado after seeing her clever designs on the Instagram of her Philadelphia-based store Yowie.

"We use a lot of bright colors because we wanted this to be a celebration of who we are […]. No heavy leather. No dark woods. That doesn't induce joy," Austin explained. Maldonado modeled the space to feel like a living room. "I felt like pattern, texture, and color were going to be important in getting across these layers about generation and how people assemble a space or home," Maldonado explained.

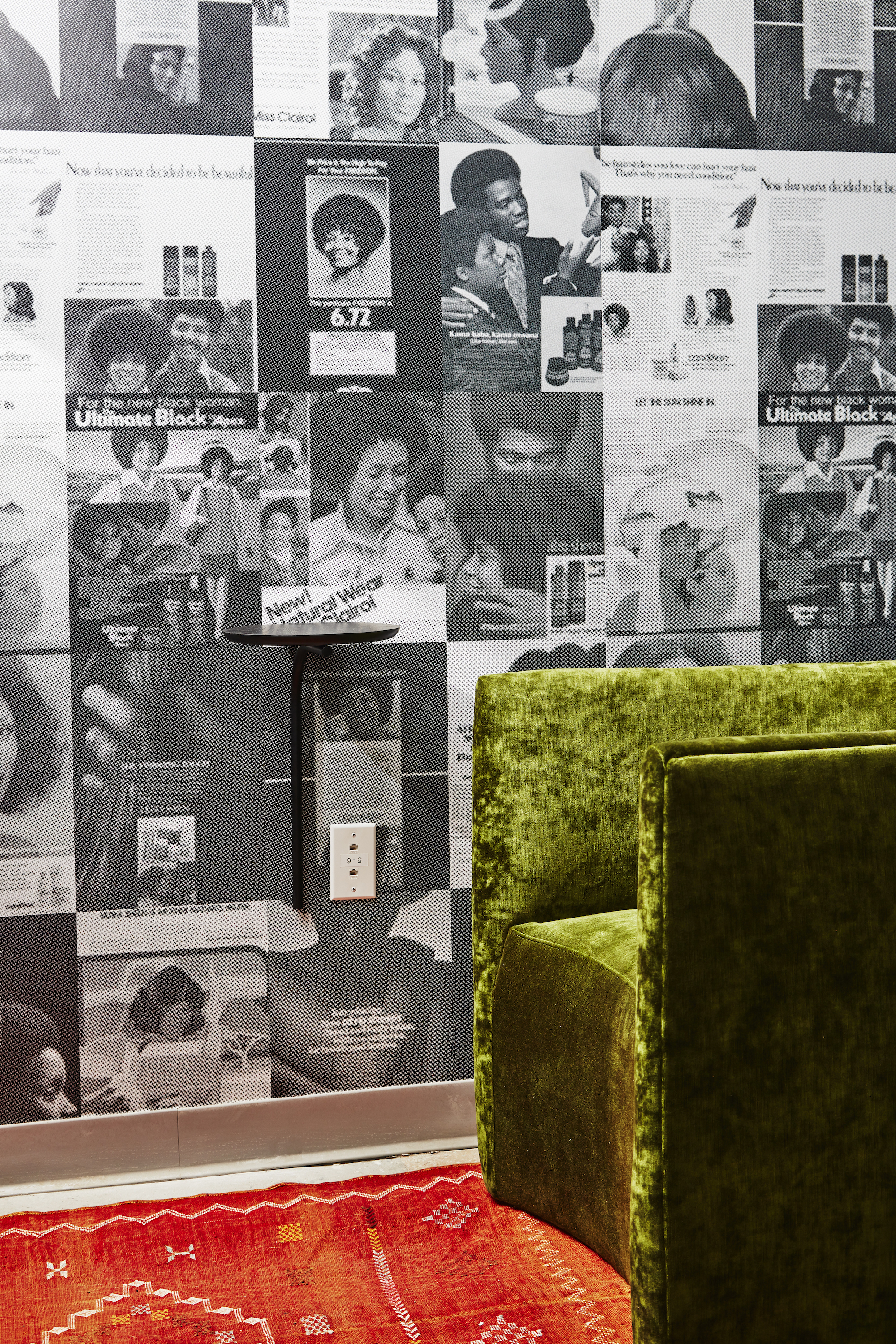

That led her to flip through library books showing what homes look like in other cultures, and to think back to her own memories of sitting at her kitchen table as a kid. The resulting club is full of small nods to home—like the collage of 70s Black beauty magazine ads wallpapering a phone booth—that remind Austin of the kind of casually beautiful things that used to lie around her grandmother's house.

Another huge benefit of a central location is that it makes it much easier to provide a fixed platform and space to connect people, as well as their projects and art, to each other.

"One of the things I was thinking about when I named it Ethel's Club was this idea of a Renaissance man reclaiming culture," she said. "I feel like that word is thrown around every which way now, but I'm trying to give that a meaning or make it mean something."

The club's art curator, Stephanie Baptist, for example, used to curate popular Black art shows called Medium Tings out of her living room to maintain her creative agency outside of the white museum world. Similarly, when one of the new members, Dominek Tubbs, first discovered the club, she had just finished creating a solo art show about the alienation of people of color inspired by her experience as one of the only Black women at her advertising agency. The club is playing a similar role across industries, exposing members to new authors, zine-makers, podcasters, photographers, restaurants, food retailers, and the like. At their opening reception party Saturday night, crowds were huddled around the back tables flipping through books on mixtape cover art and the history of Black cinema posters, while Austin joked that they were supposed to be partying.

The club also wants to bring its curation to new heights with its programming. "I want our programming to curate the best first people that you don't know and six months later you see them on Broadway," said Head of Brand Experience Vanessa Newman, a creative strategist who offered to freelance for the club after reading about it in the New York Times. "For artists that you do know, oftentimes they're making work in the confines of white institutions. I'd love to be able to give them a chance to make things for people that look like them without the pressures of wondering, 'Will this sell? Will this perform? Will I have an all-white audience? Will this piss somebody off?' And just see what kind of work is produced when those social pressures are off."

The club hopes to be able to offer artist residencies down the line; their initial events calendar includes a choreographed performance by musician Madison McFerrin, a talk with tattoo artists of color from Ink the Diaspora, screenings of classic films with live scoring, and multiple live podcasts.

One of the club's biggest missions though, is to help their members with mental health and general wellness. "I don't think that people of color can get ahead without having those coping mechanisms and that mental health awareness," Austin said. One of the few private spaces in the club is a small "wellness studio" that members can use to meditate or relax when various practitioners aren't using it to hold classes or therapy sessions. Austin is quick to hedge her speech about wellness with the disclaimer that she doesn't claim to be able to fix the mental health of all people of color, but she believes integrating it into work and social life is an important first step. The club will also be bringing in a slate of therapists for members to do free consultations with to help get around the difficult maze that is finding a therapist of color in New York. On the programming side, that looks like anything from outdoor yoga classes, to incense making, healing through songwriting, or even a series on how to build healthy work relationships.

"A lot of us are coming from these white organizations where team collaboration culture isn't healthy," Newman said. "Often people of color are pitted against each other to see who's going to make it out on top, so [our series on health collaborations] is about unlearning and healing from that, and hearing about how other folks have built healthy collabs."

While the club could sound like a utopia in some ways, its limited membership and price tag makes it essentially inaccessible to the majority of young professionals of color in the city. A full yearly membership costs $195 a month or $2,100 a year, while a part-time membership that provides access to five events a month is $65 a month or $600 a year. While its full membership price may be on par with a number of other social clubs and coworking spaces, it's not the most affordable for low-income emerging artists of color who could benefit from exposure to the club's new networks. The incoming member cohort has a number of people in creative-adjacent fields like marketing and media, as well as some full-time artists. But Newman mentioned that the hope is to be able to offer more artist residencies and working memberships or trades as the club grows. The number of memberships available will likely be the first thing to change, though, as the club's organizers are eager to expand the original location into other parts of its largely unoccupied building, as well as launch new locations around the city.

As the club gets larger, it could also face the threat of being sued by people who don't appreciate its focus on exclusively serving people of color. It's not illegal in New York City to focus programming on a specific racial group, but excluding members based on race, gender, or other protected groups is. The Wing altered its membership policy to include people of all genders back in January after a man filed a $12 million gender discrimination lawsuit against the company. Austin said she saw a similar threat from a Twitter user who claimed they would sue the company when it first made national headlines in the New York Times. But she's not letting the threat of a lawsuit keep her up at night.

"It's on the table just over to the side. If it potentially happens, there is a plan," Austin explained. "But it wouldn't make much sense for someone to sue an early-stage startup. Good luck. You'll get all our millions of dollars we have stored away."

She noted that as the company launches new locations around the city and around the country, it will likely become more of a target, but she'll also have more resources to combat any legal issues. By and large, moving full steam ahead and worrying about obstacles later has lead to miraculous success; Austin has no plans of switching up now.

There's no telling what legacy the space will leave: a series of influential podcasts; a club for chefs; art curators; marketing recruiters; or maybe a TV show collaboration with the Netflix production studio opening down the street. For now, as the club welcomes its first new members this week, Austin and her fellow employees are waiting eagerly to find out.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Taylor Hosking on Twitter or Instagram.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.