What if We Treated Websites Like Federally Protected Historic Places?

Credit to Author: Ernie Smith| Date: Wed, 06 Nov 2019 13:04:18 +0000

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium , a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

When an old site announces a shutdown, here’s what generally happens: People flood the site trying to save their old content, it draws a bunch of attention, people reminisce, archivists attempt to download the data to preserve it, and engineers at that startup or giant company attempt to foil their efforts.

In the end, we lose a resource as a digital community that we once relied on, and we do so in a way that cuts off any attempt to recollect it or understand it in its given context after the fact.

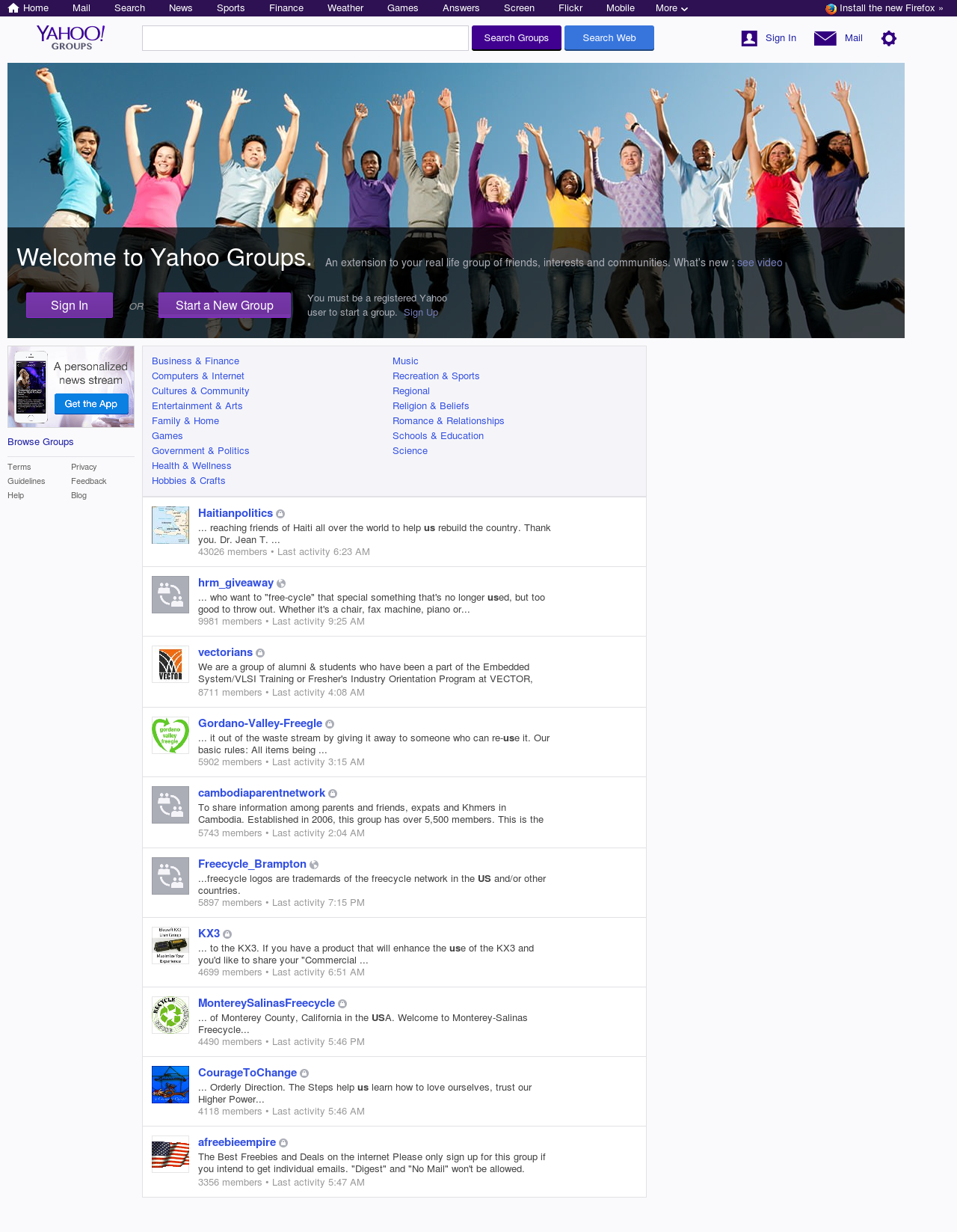

More often than not, the company most responsible for this is Yahoo, which has killed or severely damaged dozens of services since it was founded a quarter-century ago. The bean-counters killed GeoCities, a key artifact of user-generated content. Now, they’re effectively killing Yahoo! Groups.

For years, we’ve been letting go of historically relevant sites in this way. It doesn’t feel quite right.

Fortunately, the real world offers something of a better solution.

Why Yahoo! Groups reflects a long history of bad corporate citizenship

Recently, I wrote something on Twitter that might have been a little harsh given a certain viewpoint, but comes from a place of general frustration with a company that has generally not done the right thing by history.

Long story short: I called Yahoo! “on balance, a destructive force for the internet,” and noted that the company has destroyed significant amounts of our digital heritage throughout its history.

My issue with Yahoo! and its corporate successor Verizon is effectively that the company has bought and acquired numerous services over its quarter-century of existence, only to let many of them wither away—in many cases, to shut them down entirely, most infamously in the case of Geocities, a decade-ago shutdown that was effectively the digital equivalent of burning down an ancient library.

But it’s not the only one. Tools like Yahoo! Games and Yahoo! Messenger have met their maker over the years thanks to shifting corporate decision-making. Some of these sites were very well-known and memorable. Others were quickly forgotten.

The reputation for corporate sunsetting was so prominent that when the company bought Tumblr in 2013, it made a promise that it would not “screw it up.” Which it then proceeded to do.

Verizon has been slightly better at this: Instead of simply shutting down sites, it’s attempted to sell them to owners that actually make sense for the tools, as it did in the case of Tumblr and Flickr.

But Yahoo!’s tendency to do this reflects a set of purely capitalistic motivations for keeping a historically or culturally significant site online—something that could certainly be said of both Geocities and Yahoo! Groups, which just announced its shutdown. The problem is that cultural heritage, while it may start out with commercial roots, often has more than commercial considerations to keep in mind. In the physical world, if a commercial market became iconic—think like Pike Place Market in Seattle—steps would be taken to protect that market’s integrity, even if there was a downturn in its viability.

Part of what allows that is the National Register of Historic Places, on which Pike Place Market is included. We don’t have a digital equivalent to this right now.

Given the tendency for popular services to shut down with no say from end users, perhaps we need one.

Why we need a digital equivalent of the National Register of Historic Places

Our cultural landmarks are only there because we decided, as a culture, that they’re important enough to protect.

Because, let’s face it, if they weren’t, we’d be quick to get rid of those places—be they vintage storefronts, iconic neighborhoods, impressively designed homes, or works of art.

A clear passion for saving these works helps keep them alive, and it’s an act supported by U.S. law—specifically, the National Historic Preservation Act, signed by President Lyndon Johnson in 1966.

The law gave the Department of the Interior access to resources that allowed for the creation of a registry of historic places, along with the ability to hand out matching grants to buildings supported through that registry.

Before that law passed, such efforts were managed through the assistance of philanthropy, or even private interest—after all. But these factors didn’t have the backing of federal law behind them. And the act made it clear that it was somewhere that the government could help. A passage from the law:

Although the major burdens of historic preservation have been borne and major efforts initiated by private agencies and individuals, and both should continue to play a vital role, it is nevertheless necessary and appropriate for the Federal Government to accelerate its historic preservation programs and activities, to give maximum encouragement to agencies and individuals undertaking preservation by private means, and to assist State and local governments and the National Trust for Historic Preservation in the United States to expand and accelerate their historic preservation programs and activities.

The act and its updates over the years do a few things: It combines government and community support for the long-term preservation of a community resource, it creates a review process for handling “adverse effects” in the community that could threaten the shape of the historic landmark, and it indirectly encourages the hiring of cultural workers such as historians and archaeologists that can help protect and manage historically important places.

A good recent example of the work of this law in action comes in the form of the Obama Presidential Center, which is currently being planned in Chicago. Working in the framework of the act, a review found the new structure would have an “adverse effect” on nearby Jackson Park. This process allows the builders of the center to make changes to help minimize and limit the impact of those changes, the community to discuss it, and all sides to come to a reasonable solution that limits adverse effects.

The effect of the law, in the long run, is that if a place is important enough to protect, there’s a system in place that can help encourage that protection and even go so far as to promote the historic place. On a website dedicated to the 50th anniversary of the law, it’s noted that federally managed rehabilitation efforts have helped to save more than 38,000 structures, while creating 2.3 million jobs and $106 billion in investments.

Of course, historic places are often thought of as physical things, even though many of our meeting places and artifacts online often taken similar roles to the physical places that are found offline.

Much like the physical spaces, these digital spaces are constantly under the threat of change, “adverse effects,” or even dismantling. You never know when a bulldozer is going to show up to take down your digital summer camp.

To a degree, this is understandable, because often these sites are run by businesses, and businesses often fail. Sometimes, it’s a failed experiment that didn’t necessarily go anywhere. Sometimes, it’s a project that didn’t succeed in its original context.

But there are often platforms that carry so much historic significance to the internet that dismantling the tool makes the entire thing a worse place.

Currently, the only party that is allowed to make a decision on whether to shut a service down is the organization that runs the service. Often, no alternatives are offered. It’s their way or the highway.

Many companies have dealt with this to some degree. With Google+ and Reader, for example, Google has killed two very popular services that served important cultural roles. But Yahoo! has run into this problem so many times, so repeatedly, that it makes one wonder if they should have the right to make the call without actually talking to the community first.

Even with all the branding and marketing and everything else, a degree of that ownership gets transferred to the community with a site like Yahoo! Groups, and to not give the community a say over its long-term status.

“We will get right to the point: Electronic Arts Inc.’s legal team has contacted us and nicely asked us to stop distributing and using their intellectual property. As diehard fans of the franchise, we will respect these stipulations.”

— A message from the Revive Network, a volunteer-run site that effectively ran fan servers for a number of popular online games using modified versions Electronic Arts’ game code. The servers, run by fans, effectively got around a problem largely caused by EA and other large game-makers in recent years: The shutdown of servers for old game content, out of interest in ensuring that players upgrade to newer games. However, in 2017, they were shut down because EA complained. Last year, the Library of Congress made a series of exemptions for the archival of video games with online components, but put in restrictions that effectively bar the game from being run without legal access to the server code. While not the same issue as being listed here, it’s very much in the same spirit.

A recent court case involving Domino’s Pizza could provide a framework for setting digital places as historic ones

Depending on how you look at it, the owners of Domino’s Pizza either dodged a major bullet recently, or a large swath of the public with disabilities did.

See, the pizza chain, which has put significant effort into revitalizing its sales through the addition of online time-tracking gadgets, was the subject of a lawsuit after a blind man complained that the site wasn’t accessible under the Americans with Disabilities Act, and the company offered no equivalent to him or similar users.

The pizza conglomerate, having money and in a field that has famously fought against regulation of things such as calorie counts on menus, fought this interpretation of the ADA, arguing that the law’s definition of a “public accommodation” should not include digital platforms such as websites and mobile applications, and that it creates a slippery slope where all sorts of websites, big and small, could run into legal issues if accessibility wasn’t part of the master plan.

The company was already losing its case when it brought its case to the Supreme Court; the high court chose not to pick up the case, which prevented the justices from effectively gutting the law for use on the internet. But it also ensured that the ADA wasn’t explicitly applied to the internet, either.

The use of the term “public accommodation” in the ADA was just vague enough that it left open a question regarding whether virtual places counted under the law. The vague nature of the law’s wording has left things open just enough that many companies have simply built for accessibility in mind. Eventually, the Supreme Court might clear this up, but it’s a case where the uncertainty actually helps the public at large.

Likewise, the National Historic Preservation Act, benefits from a degree of uncertainty over exactly what it covers. As written, the law allows for the Secretary of the Interior “to expand and maintain a national register of districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects significant in American history.” While it clearly leans on the ideas of buildings and structures, it is not so prescriptive with its definition that things that aren’t physical structures could be excluded from the law. You could make a case that “sites” and “objects” could fall under a digital realm if so allowed. And if you need to insist on something physical, the actual server farm probably fits the bill.

So there’s a case that, if the Department of the Interior was so directed or inspired, it could start a preservation program for digital works under the current law, and while I’m not a lawyer, it could stand a decent chance of holding up in court, based on what we’ve seen with Domino’s Pizza LLC v. Robles.

The challenge here involves a will and a desire to do so, along with funding considerations, and that’s where such an approach might fall flat.

In an email, a spokesperson for the National Park Service, which operates the National Register of Historic Places, noted that the law wasn’t being used in this way: “As of right now, there is no effort that I'm aware of to preserve or archive websites under this law or with the introduction of another.”

Certainly, other channels for archival exist. But while the Library of Congress operates a web archive, and there’s certainly the nonprofit work of the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, no effort to keep websites at their current domain, in pristine condition and preserved form, is in the works.

Certainly, the Trump Administration wouldn’t be interested in doing something like this considering how low it is on their list. But if someone else with an interest in digital culture and consumer protections took over in the White House?

Hey, it’s possible, and it could open up new avenues for historic preservation. By mitigating purely commercial motivations, it could ensure that our digital heritage isn’t so easily deleted in the future.

Too often, our cultural artifacts are placed in the hands of businesses or outside organizations that don’t fully appreciate the cultural value of what the artifacts are, especially if they are no longer profitable.

I don’t think that businesses should be blocked from shutting things down, but it would be nice if the community using a highly culturally relevant website or platform had a say in what happens to it before its ultimate demise. Currently, they have no say—and that’s not good enough, when companies that have the money and generally know better generally hold all the power over huge swaths of our digital heritage.

We can’t save Geocities or Google Reader or Yahoo! Games or all of these games Electronic Arts killed—it’s too late for them. But we can create a context of preservation around the next sites of this nature, by stating that they are considered important enough by society to be saved, that the community has deemed them important enough to preserve and protect. The company that made it has a role in the decision-making as well, but they have to respect the historic value of the work—they can’t just kill it.

And that can potentially open up new avenues to keep these sites alive. You likely could not put a paywall in front of a site like Yahoo! Groups, which is paid for by advertising. But by making it a “historic place,” it opens up new directions for its business model, because the goal becomes about simply maintaining what’s there, not maximizing its revenue. And the kind of people that will show up are there to look at this information in a new context.

The content becomes like an old newspaper, a tool for research rather than something you might regularly use. And that’s as it should be. It gives the past its desired weight, while not getting in the way of the future.

We need to take this decision-making out of the hands of companies to a degree. Their motives are different from yours and mine. Preservation isn’t in their DNA.

But it could be.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.