‘Death Stranding’ Shines When You’re Delivering Packages in a Haunted World

Credit to Author: Rob Zacny| Date: Fri, 01 Nov 2019 13:24:43 +0000

Late in Death Stranding, a major plot thread is tied-off when a character walks back into a scene and says, “I brought you a metaphor.” It’s a funny line that fits both the character and the moment, but it also serves to lampshade what begins to go wrong in the last act and epilogue of Hideo Kojima’s metaphysical sci-fi epic. Atop an interesting premise where the border between life and death has broken down and been transformed into a new frontier for exotic resources and technology, Death Stranding begins piling on more analogy, and turning decent subplots or bits of backstory into feature-length drama.

It also turns away from its best version of itself: Gone is the elaborate walking sim and survival game that easily occupies 20-30 hours of Death Stranding’s over-blown length, and in its place comes at last, the self-indulgence that one expects from a Kojima game but without the audacious, elaborate proceduralism. The incredible attention to detail, to bringing small actions and gestures to life with thoughtful controls and and precise feedback, drops away. Instead the last act reinvents itself as a series of setpiece missions, long cutscenes, and boss battles that feel at odds with what’s come before.

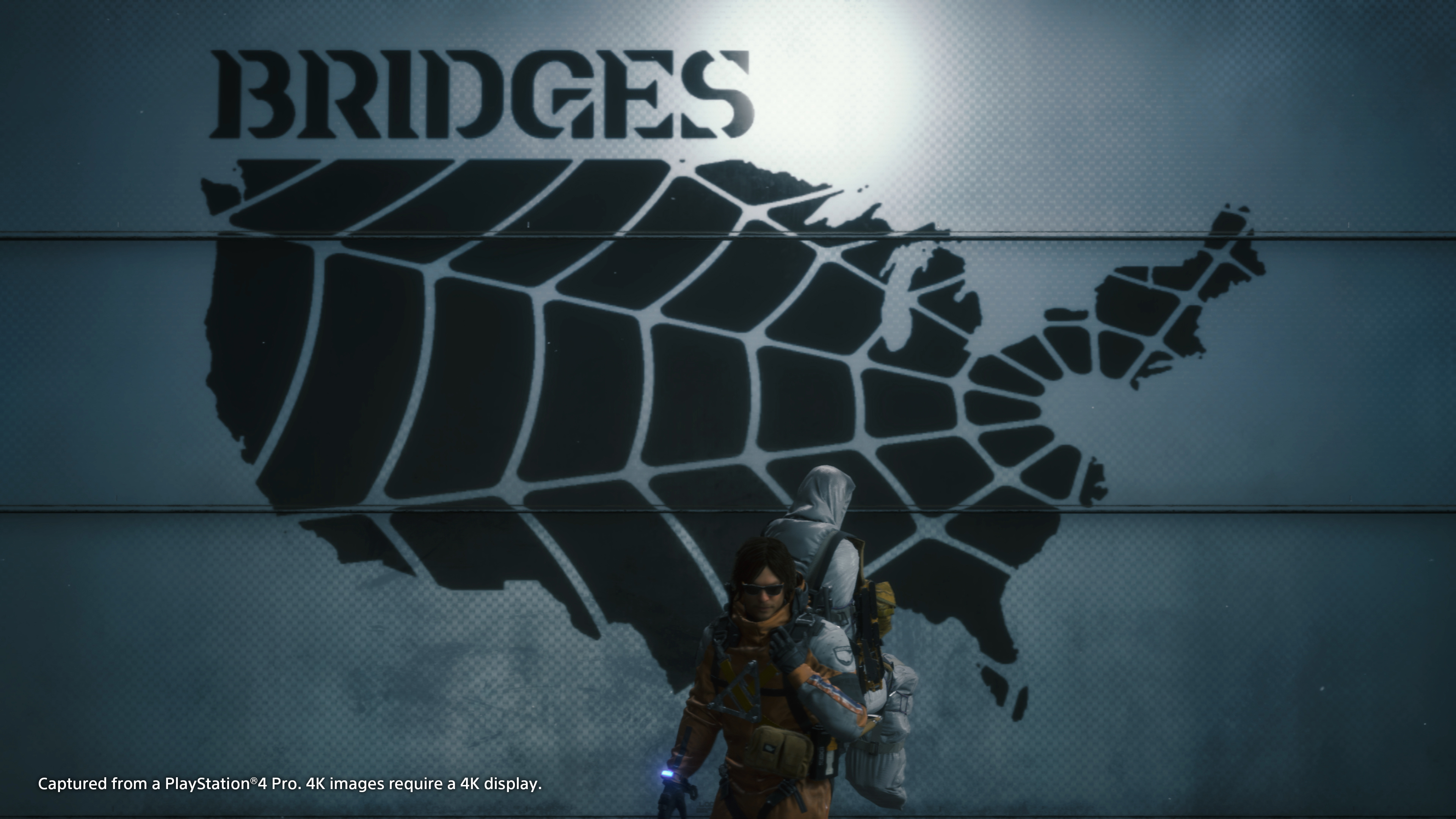

But it’s what precedes that last act that will largely determine how you feel about Death Stranding, a game of rich mundanity in a newly-haunted world. You play Sam Porter Bridges, an elite, danger-defying courier for the Bridges company that serves as combination mail service, telecom utility, and manufacturer for the beleaguered United Cities of America. The United States is a memory, effectively destroyed along with much of the world when the Death Stranding event occurred and the dead began crossing into the world of the living, causing explosive catastrophes on the scale of a nuclear war. Now the country is reduced to a series of strongholds and survivor’s camps, and most of the actual functions of government are outsourced to Bridges.

The spirits of the dead are undetectable to most people, but will attempt to drag anyone they encounter into the limbo they inhabit, with the aforementioned explosive results. So it falls to a handful of couriers like Sam to travel between these settlements and maintain a semblance of connection and identity between them. In practice, this means a lot of long journeys on foot or on wheels, with heavy cargo in tow.

That makes Death Stranding first and foremost a kind of job-and-walking simulator, or perhaps more accurately, a backcountry hiking simulator. It has weapons, it has stealth mechanics, it has different enemy types who populate its world. But it’s nowhere near as interested in any of those things as it is interested in the way each footfall lands on broken ground, how you move differently when you’re carrying extra weight, depending on where you are carrying it. For one trek to a distant mountain peak, I over-prepared with gear and forgot that each new item would add to the comically growing pile atop my character’s backpack. I had tons of climbing gear and weapons to deal with anything I might encounter… but it also meant that I’d turned my cargo into a giant sail. The moment I hit a blizzard near the summit, my character was spun around and then hurled down an icy slope, and sent a small avalanche of broken equipment boxes into the valley below. Death Stranding always wants you to think about speed versus safety, and to consider the hidden hazards that can only be avoided with forethought and care, not a tool.

It mostly succeeds at these ambitions. It maintains a sense of dull, focused tension as you consider each step of your journey, and each forking the potential path in light of the tools at your disposal. With a light cargo and good supply of ropes and ladders, forbidding cliffs can be become easy shortcuts. With a heavy cargo and a shortage of climbing gear, even gentle slopes become potential catastrophes. Sometimes this deliberate pacing and thoughtfulness gives way to a relaxing sense of success and freedom, but at other times it continues to build into a nail-biting crisis as one small misjudgment or stroke of bad luck creates another. You took the wrong way over a hill and instead of a gentle pass between peaks, you find yourself navigating deadly, snowy cliffs as every step leaves your character more tired, and consequently, clumsy.

But as I said, the dead now haunt this world and there are special complications you’ll encounter. While your character can detect the spirits of the dead when they are very close, to “see” them at a distance requires the help of a Bridge Baby (a BB) who is entombed within a small glass sarcophagus worn by couriers. Taken from women who suffered brain-death at some point in their pregnancy (“stillmothers” in the game’s frequently chilling parlance), the BBs are connected to both the living and the dead. Regarded as tools by Bridges, it’s not long before their awareness and attendant personhood begin to come into play even as they help with the mechanical task of detecting invisible monsters.

Likewise, the world has a measure of human-caused chaos as well. In addition to “terrorist” groups who seem to have given themselves over to pure violent nihilism in the face of this new age of restless spirits, there are gangs of bandits called MULEs who want nothing more than to steal cargo and deliver it for themselves.

The backstory on the MULEs is interesting and points at a frustrating ambivalence that turns through much of Death Stranding. The MULEs are couriers like Sam who got hooked on the “high” of fulfilling tasks and delivering packages, to the point where it is all they want to do and will steal cargo just so that they have more to deliver themselves. It’s not hard to read them as a commentary on the kind of completionist style that a lot of modern video game design tacitly encourages with endless, randomly generated missions and daily goals. MULEs are basically players themselves… but then Death Stranding gleefully employs many of those same features it is critiquing.

I don’t mind an ironic critique of media conventions, but it feels slightly manipulative here. Death Stranding creates a caricature of the exact type of play that it encourages, which makes me feel less like the audience for an argument than one of its objects.

There’s a similar line of discussion happening around Death Stranding’s central conflict, between the ways that technology can bring people and communities together, and the ways that it is powered by and drives many of the same forces that contribute to worsening social and ecological collapse. It takes the game’s sharpest metaphor and makes it progressively duller throughout the story.

While the bleed-through of the world of the dead into the world of the living is a global catastrophe, Bridges has also found opportunity there. On the “beaches” where the dead gather before passing on, like the shores of the underworld, time passes very slowly compared to the world of the living. That means that things like computers can perform vastly more calculations in “limbo” than they could on Earth, or that communications can break the limits set by the speed of light. The world of the dead has also supplied the living with a miraculous and exotic new material, chyrellium, that is used for the instant fabrication of just about anything. Even the “timefall” rains that accelerate the cycles of growth and decay where they land on earth have been turned into speed-boosts for clever farmers.

But the beaches are also places of mass death. The too-familiar image of whale pods beached and decaying in sickly shallows is the predominant aesthetic of Death Stranding’s world of the dead. When the world of the dead invades and destroys our own, it does so via vast lakes of oil, churned by the spirits of the dead. Death Stranding is fixated on the tension between incredible technological progress and the mass death and ecological disaster that have attended it. As Sam goes through the world, he is making it more and more dependent on the force that may be driving it to Armageddon.

Death Stranding knows this, just like it also knows the various ways that games and social media try to manipulate human psychology to foster engagement and dependence. But it evinces no tension between that awareness and the relentless praise it showers on Sam and the player. Nor does it ever directly question the overall meaning of his quest. The company and technologies he is serving might be bad, but the game also repeats at every opportunity how meaningful his job is because it brings people together. How? Usually by delivering consumer goods and hooking people up to the internet.

I harp on this in part because in general I was pleasantly surprised at how effective Death Stranding’s world-building, backstory, and characterizations were. Especially given how disastrously things start off with the introduction of a cast of characters with names like Die-Hardman, Fragile, and Deadman, which played into every preconception I brought with me to Death Stranding. I was only introduced to Kojima by some die-hard Metal Gear fans with Guns of the Patriots, and found that game both impenetrable due to its self-reference and deeply off-putting thanks to an overtly juvenile and sexist authorial voice and directorial gaze. Death Stranding is hardly subtle, but its clean slate liberates it from the weight of series history that Metal Gear increasingly struggled to bear, and if it still has an objectifying camera, it’s no longer leering and the character designs are more functional than stylized or sexualized. For a game whose marketing sometimes seemed to imply weirdness for its own sake, Death Stranding mostly wrestles with relatable and pressing fears and dread. But that also makes it all the more frustrating when it casts those themes aside for a facile homage to video games and “making connections.”

Just as Death Stranding sabotages some of its own text, it increasingly pushes players toward combat against the dead and the living, with systems that feel a lot less rewarding than those used for exploration and traversal. The deadly spirits haunting the land are mooted by a spirit-killing hand grenade early in the game, and later a spirit-killing machine gun. Likewise, in a world where dead bodies quickly cause deadly encounters between spirits and the living, violent homicide is nearly unheard-of. At first this imposes a neat problem when it comes to bandits, because you really can’t just shoot them. But then Death Stranding gives you a “nonlethal” assault rifle, shotgun, etc.

Functionally, it turns itself back into a conventional shooter, when its best experiences are centered on workaday nonviolent problem-solving, with limited collaborative and social elements as items, constructions, and even caution and advice signs propagate between different players’ sessions. It genuinely warms the heart when you find someone else’s ladder or a shelter in a useful spot, just as you were about to get stuck in some real trouble.

For two-thirds or more of its length, Death Stranding is generally that best version of itself. But the last third’s focus on grueling boss battles and sudden resource starvation end it on a disproportionately sour note. The game doesn’t really get much harder, but its hand-to-hand and shooter-boss battles emphasize the clumsy inertia of your character in a way that’s far more frustrating than fun. It also compounds its narrative and thematic issues by entering a mostly expository mode of storytelling. If its mysteries and weird implications are a major part of what makes Death Stranding appealing, its compulsive need to over-explain starts leeching a lot of the joy from that.

It’s a shame it ends poorly, but that doesn’t totally wipe away what it accomplishes prior to that. Death Stranding is a fun, immersive suspense game about people doing fairly ordinary and boring jobs in the face of terrifying and unknowable dangers. The world needs saving, so it’s just a matter of adding it to Sam’s route.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.