Mexico’s Rehabs Are Terrifying

Credit to Author: Deborah Bonello| Date: Fri, 25 Oct 2019 17:34:59 +0000

CARTEL CHRONICLES is an ongoing series of dispatches from the front lines of the drug war in Latin America.

“I’ve been in places where they’ve hung me up by my legs, covered me in shit and made me eat caldo de oso [a soup made of rotten vegetables]. They think that beating people up and screaming at them that they will die is going to make them stop using drugs,” said Enrique Martinez, aged 55, who was addicted to heroin for 35 years in the border city of Tijuana, Mexico.

Before he got off heroin, in the bonafide rehab center called A New Vision that he now helps run, he was interned in one of the thousands of clandestine, unregulated drug treatment centers around the country, known as anexos.

Mexico, currently in the grip of the worst cartel violence since the start of its “drug war” more than a decade ago, is now also struggling with a growing drug addiction problem. Yet its drug treatment system is in disarray.

With limited and inadequate state resources, the government of President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, which took office in December, is leaving many drug users in the hands of an ill-equipped and hellish drug treatment system which has seen many vulnerable users kidnapped, abused, and beaten. Just one in ten private rehab clinics operating in Mexico has official permission to do so from the country’s anti-addiction agency, say experts who work with drug users. Other sources estimate a quarter of rehab clinics are registered .

Drug use generally across Mexico has nearly doubled in recent years, according to the government census on drug consumption. But worryingly this includes a doubling in the use of the addictive stimulant crystal meth, known as ‘cristal’ in Mexico. Over the last decade, the huge amounts of meth produced in country by Mexico’s powerful drug syndicates has begun to diffuse into the wider community, increasingly pushed onto the streets by vendors.

“[ Cristal is] a threat because it’s very accessible and its super addictive,” said Gady Zabicky, the head of Mexico’s federal anti-addiction agency, CONADIC. But Zabicky admits that there simply aren’t enough state-funded clinics to tend to Mexico’s growing army of addicted drug users. In the state of Guanajuato, where meth use has spiked alongside homicides, demand for treatment for cristal use has increased seven-fold in recent years, according to government figures.

Jose Gomez, a psychiatrist who treats drug users at one of the government centers in Guanajuato, said that they treat around 2,000 people a year, largely for cristal, but that demand far oustrips what they can offer. “We need to open more spaces [for drug user treatment]," he told VICE.

So the government outsources its addiction problem to a vast network of private centers for treatment. Some of which are good, but most are either unreliable, shambolic, or dangerous. Government oversight and monitoring of these clinics is minimal. As an example, half of the hundred or so drug users in the New Identity clinic VICE visited in Mexico City had been placed there by Mexico’s social services agency, the DIF. One of them was an 11-year-old boy.

The good, registered clinics can charge as much as US$1,500 for the minimum three-month program inmates are put on. But these are for the few. With a lack of free government rehab options, families desperate for help with their addicted loved ones turn to these private clinics, only one in five of which are registered with the authorities, the experts I spoke to estimate. There are some 2,200 clandestine clinics operating around the country, according to Zabicky. But there are likely more: Ruben Diazconti, who works with drug users in Mexico City, told VICE that he thinks in Mexico City alone, there are as many as 1,800.

In recent years, some centers have made efforts to get on the government register and conform to official norms, others—the anexos—have been driven underground by those pressures. Nearly all of these private centers are run by and employ former drug users.

Patients who are interned in rehab centers—both registered and unregistered—are often kidnapped by employees and held against their will. Their families, meaning well and at their wit’s end, sign away their freedom. “It’s very common that people get tricked into thinking they’re going somewhere but instead they’re taken to these centers against their will,” said Carlos Zamudio, an independent investigator on drug markets and consumption who wrote a report about drug treatment centers for the Open Society Foundations in in 2016.

Interviews with drug users in Guanajuato, Tijuana, and Mexico City confirmed this is a common practice by both registered and clandestine clinics. Even municipal police are sometimes contracted by families or clinics to take patients to these centers against their will, said users and observers.

“I was asleep in the night and they woke me up,” said Ceci, 20, who spoke to VICE in the New Identity center in Mexico City. “I was super drugged up and it was awful. I didn’t want to come and [the people from the center] tied my hands and feet and I was screaming my head off. They carried me out because me parents signed a form—I was under 16 at the time.”

Ceci started using drugs when she was 13 and has been in and out of clinics for much of her young life. She was most recently interned here for her meth use. This is her fourth stay at this center. This final time she came of her own accord but the other three she says they came for her.

The practice of emotional and physical violence by anexos to cure addiction is commonplace, according to Zamudio. “They say that those methods are the only way addicts learn and value their lives,” he said. His report estimated that at the time, some 35,000 drug users in Mexico were in centers operating outside of the law.

Another unnamed victim, who Zamudio interviewed for his study, told him: “My dad brought me in with lies. He asked me to come along to my uncle’s house to get some stuff. We went there and some men came over. When they tried to put me in a van, I got pissed and so they tied me up with my feet and hands behind my back.”

“They tied me up as if I were a slab of pork,” said another. “They caught me from behind, tied up my hands and feet and [when] I arrived to the group, they put me in a place that they call the morgue…There they checked me and someone tells me to lie down. They tell me this will be your bed, today you will stay here until you sober up. Well, ever since I entered that observation room or morgue as they call it, I could hear people screaming. I would hear them at three in the morning, all the cursing.”

Legal or not, rehab centers aren’t doing the job they set out to do—even the ones with good intentions. “People just leave feeling bitter and damaged and start using again,” said Martinez in Tijuana.

These clinics have become a decent business for some owners who can manage hundreds of patients at a time, but they’re not solving the problem of addiction. Alfredo Segura, at the New Identity registered rehab center in Mexico City, said he has just a 7% success rate with patients. This is very low compared to the success rates claimed (but rarely proved) by the majority of rehabs, but Segura was being honest about the difficulties of kicking addiction.

Zabicky said the other problem with Mexican rehabs is that the treatment they give is one size fits all, regardless of whether people are coming in for help with alcohol, heroin or cristal use.

But it’s not just meth that is causing problems among Mexico’s increasingly distressed population. In the north of the country, on the U.S.-Mexico border, opioid overdoses—rarely recorded in autopsies in Mexico—are on the up.

Mexico has been spared the opioid epidemic sweeping the States. Yet now observers who work with drug users in the cities of Tijuana and Mexicali are detecting fentanyl through tests on white powder, sold as heroin and called China White.

Mexico’s cartels started producing fentanyl in clandestine kitchens in states such as Michoacán, Guerrero, Sinaloa and Baja California a couple of years ago, in response to growing demand for the synthetic opioid from users and dealers in the United States. Like with meth, fentanyl is also seeping into Mexico’s drug diet, a bi-product of rising heroin use and domestic production of the highly lethal synthetic opioid.

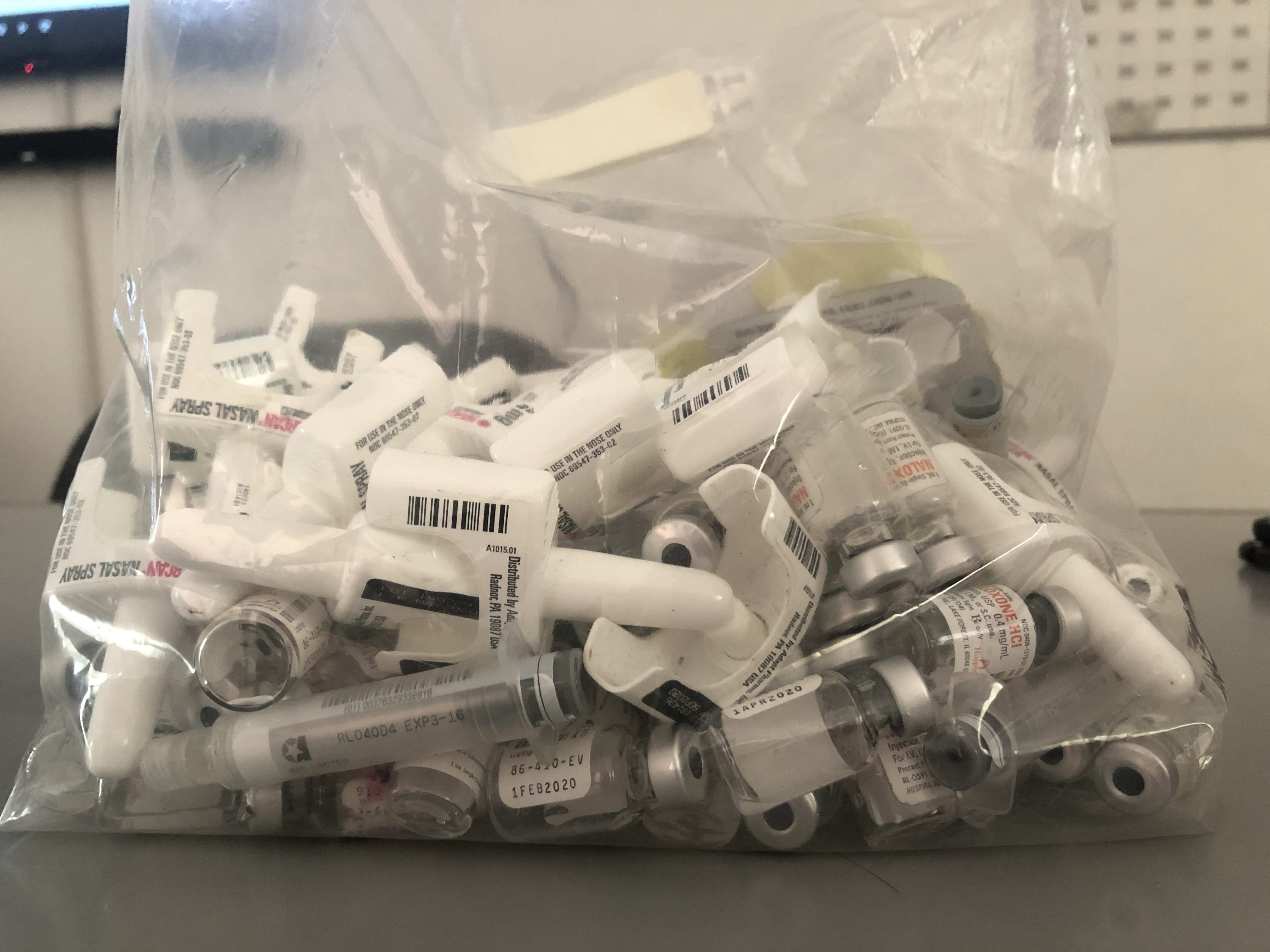

“It’s with the arrival of 'China White' that we have started to see so many overdoses,” said Luis Segovia. He and his colleagues at Prevencasa, a drug harm reduction NGO which runs a needle exchange in the north of Tijuana, have started handing out naloxone spray to users, a medication that reverses opioid overdoses if someone can administer it to a dying person in time.

His colleague Alfonso Chávez does the daily rounds on the blocks close to the center. Down a nearby alley, users cluster together on a curb, some of them nodding in and out of consciousness. Chávez hands them each naloxone, so it is on hand if someone ODs. Chávez chastises Yolanda, a middle aged user, for picking up a dirty needle from the ground and preparing to use it. He says naloxone—known under the brand Narcan in the U.S.—is prohibitively expensive in Mexico. Prevencasa has to rely on international donors, not the Mexican government, to fund its supply.

A two hour drive away, in the border city of Mexicali, heroin user Julio Moreno, 31, told VICE that he tried fentanyl for the first time in September. “It made me really stupid,” he said, but he liked it because it was so strong and so knowingly uses it. Verter, a community center there that works with drug users, tested the syringe he used to take the drug and it came up positive for fentanyl.

What the government needs to focus on, according to Tania Ramirez, from the influential nonprofit Mexico United Against Crime. is “more and better measures of drug use to improve prevention efforts—to deal with the risk factors that affect the most vulnerable populations such as children and teenagers.”

But the future does not look good for anyone with a drug problem in Mexico. President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador cut the funding to nonprofits such as Verter and Prevencasa, who are working on the frontline with vulnerable users, when he took office at the end of last year. The cuts were part of his fight against corruption, arguing that many nonprofits abuse government funds. Experts acknowledge that this can happen, but that the solution is to add a filter to the way money is handed out to prevent it falling into corrupt hands.

Meanwhile, the federal budget cuts have left organizations on the frontline of drug addiction scrambling for the resources to attend to a growing problem.

Follow Deborah Bonello on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.