Scientists Discover a New Phenomena Called ‘Stormquakes’

Credit to Author: Mika McKinnon| Date: Fri, 18 Oct 2019 14:52:28 +0000

Extremely powerful storms are so intense they can set the ocean floor rumbling, generating a newly-discovered phenomena that scientists are calling "stormquakes."

For years, we’ve seen low growling vibration of hurricanes on seismometers and a low microseismic hum of vibration from waves slamming into beaches. But stormquakes are something new.

“There's a low hum in the Earth called the microseism that's happening all the time generated by the action of wind and waves around the world drumming on the seafloor,” said Wendy Bohon, geologist and science communication specialist at the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology. The very biggest storms drum on the ocean floor with even more energy, creating stormquakes, a newly-discovered phenomena announced this week in an article published in Geophysical Research Letters.

“[Stormquakes] are seismic activity that can travel across the continent that are excited by hurricanes and large winter storms,” Catherine de Groot-Hedlin, geophysicist at the Scripps Institute of Oceanography involved in the research, said.

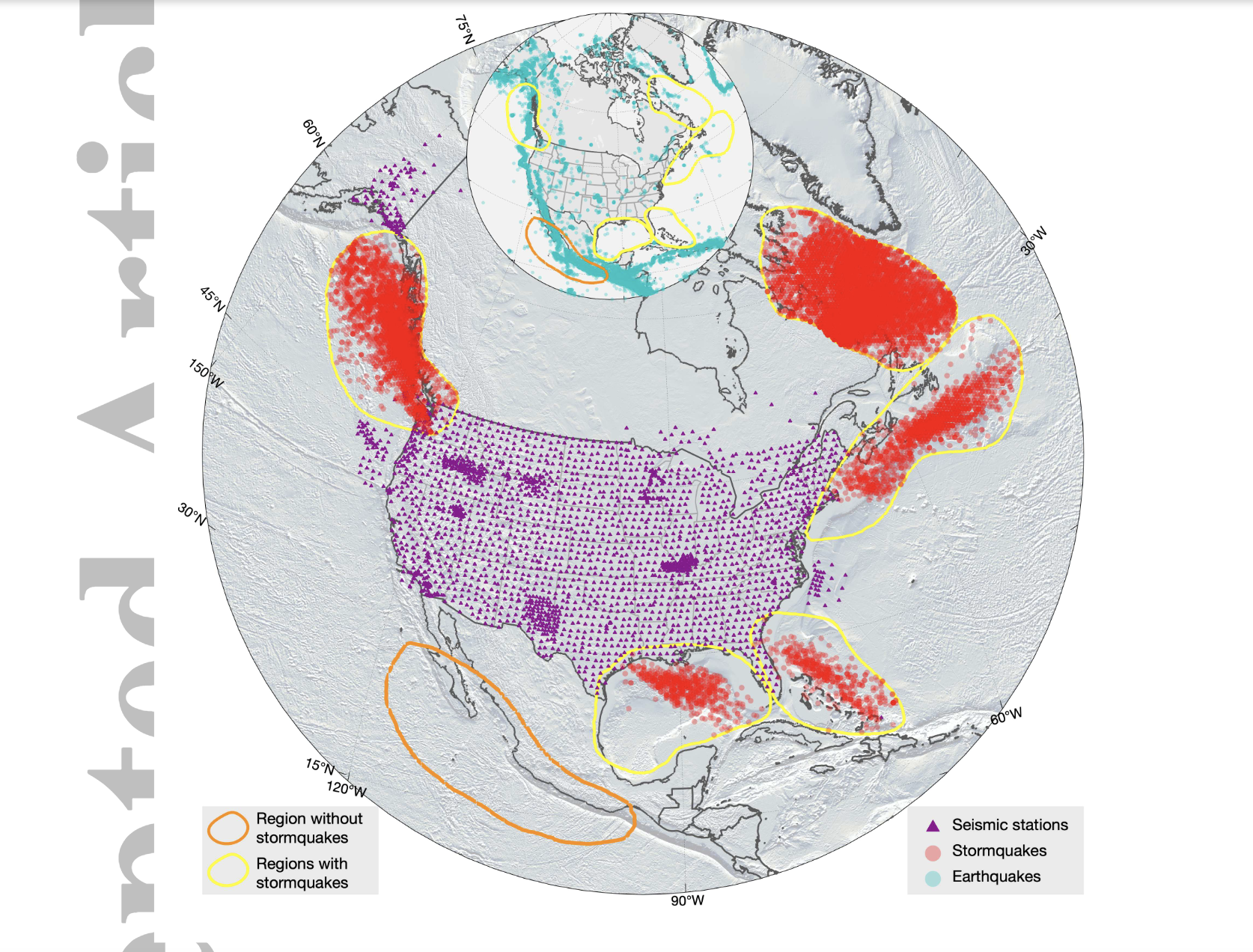

Unlike the background microseism hum, stormquakes are localized point sources that only show up in certain areas. While the phenomena is so newly-recognized that scientists aren’t entirely sure of the mechanisms yet, they have determined that stormquakes occur along technically passive margins—places that don’t get earthquakes—on broad, large continental shelves.

“It's something about the shape—or the bathymetry—of the seafloor interacting with these big ocean waves that are produced during storms,” Bohon said. “You're getting some kind of energy relief that's beating on the seafloor in a particular way, and those waves are moving out in all directions as coherent packages which we’re then able to detect using seismometers.”

With ocean waves all over the world drumming on the ground, the microseism is a mess of incoherent waves, the seismic equivalent of tossing a handful of gravel into a pond and the myriad of many-sized ripples spilling out in all direction. But, Bohon explains, these stormquakes are creating coherent seismic waves that are more like tossing a single pebble into a pond to create clean, coordinated ripples radiating from a single source.

Stormquakes were discovered by adapting a tool originally used to search for a totally different type of geophysical signal.

“I developed it for infrasound, which is sound waves travelling through the air,” de Groot-Hedlin said. One of her co-authors, Sloan Coats, noticed an unusual seismic pattern in the extremely seismically-active Cascadia Subduction Zone of the Pacific Northwest, and asked de Groot-Hedlin to modify her algorithms. “The amplitude are much lower than what we're used to seeing with earthquakes normally,” explains de Groot-Hedlin, but once they saw it, they were able to apply the same technique to other locations and soon realized it was storms, not tectonic movement, that was triggering the stormquakes.

Seismic waves generated by earthquakes, explosions, and now, apparently, storms, can be used to map what’s underground by carefully measuring when seismic waves arrive at different places on the planet. Different types of seismic waves each have different characteristics that interact in specific ways with the materials they pass through. “That gives us an idea of what's happening in the subsurface, both the wave speed, the way the waves change and when the waves stop,” says Bohon.

One of the fundamental assumptions of using background seismic waves like the microseism to map subsurface structures is that they are incoherent—it’s random noise from all directions. “That’s an incorrect assumption,” de Groot-Hedlin said, pointing out that since stormquakes only happen in particular places, they aren’t random. While stormquakes won’t directly lead to better seismic imaging of the Earth’s interior, it will lead to researchers questioning what we think we know so far.

“We can use seismometers to learn a whole lot more than just about earthquakes,” Bohon said. Geophysics is a science of indirection and creativity. “A lot of the things that we're looking for, we can't directly observe, so we have to think of other ways to look at them.”

Seismometers can even be used to study atmospheric phenomena. “There's a slight tilt in the seismometers before a tornado touches down,” Bohon said. These stormquakes are another tool for geophysicists to deploy, and both Bohon and de Groot-Hedlin agree the most exciting part will be the unexpected interdisciplinary collaborations neither of them have even thought of yet.

“Noise means whatever you're not interested in,” said de Groot-Hedlin, who is already adapting her search algorithms to listen to breaking ice, fracking, and even nuclear explosions.

“They found these signals and they've come up with this idea that's supported by evidence,” Bohon said. “But now other scientists from other fields are going to be able to use and run with it.”

“When you're kids, you feel like everything's been discovered. You read textbooks and it's just a bunch of facts,” she added. “We don't know everything there is to know. We know a lot, but we don't know everything,”

This article originally appeared on VICE US.