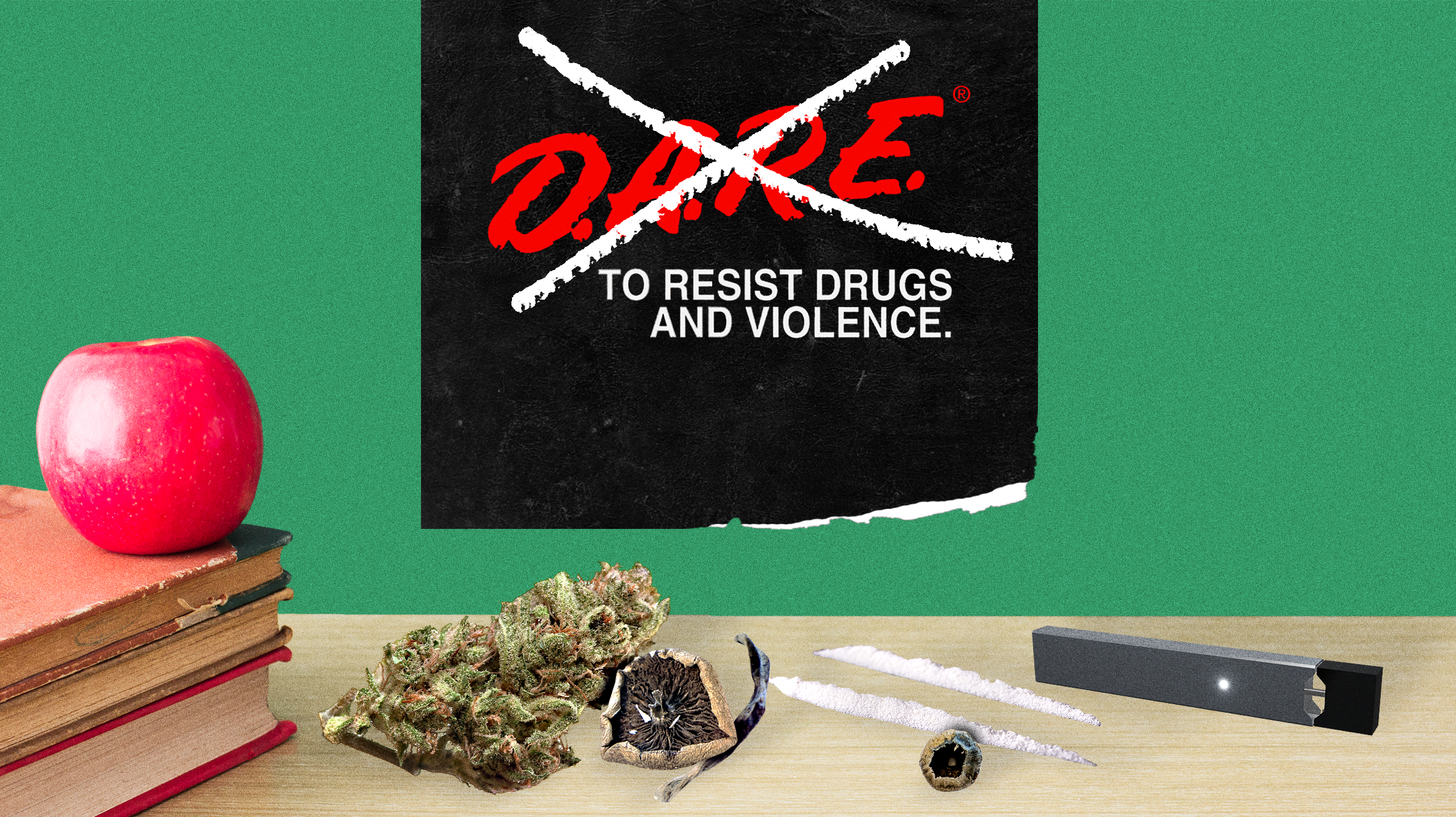

The Future of Drug Education Is So Much Better than D.A.R.E.

Credit to Author: Alex Norcia| Date: Tue, 08 Oct 2019 18:06:20 +0000

Drugs are coming to a high school near you. Or at least a conversation about them grounded in science and reality might be.

On Tuesday, the Drug Policy Alliance (DPA), an advocacy group whose self-proclaimed mission is to end the war on drugs, announced it would roll out Safety First, a brand-new approach to drug education for ninth and tenth graders. It's a model that has already been heralded as the sort of polar opposite of the old-school fear-mongering propagated by Drug Abuse Resistance Education, or D.A.R.E., in the 80s and 90s. Experts said wider adoption could offer a fresh road map for teaching kids about drug use in the age of vape panic and mass fentanyl deaths.

The "Just Say No" mantra of old relied on strident (and therefore easy-to-swat-away) messaging about the dangers of all drugs, essentially treating the entire spectrum of illicit substances as if they were the same. In contrast, the DPA's is centered on the philosophy of harm-reduction. That's the public-health belief that policy should be less focused on the complete eradication or abstinence of drugs, which will never happen, and instead minimizing needless risk and suffering.

So rather than demanding that teenagers completely refrain from doing drugs or being around them, Safety First teachers comprehensively explain specifics in 45-minute intervals over the course of 15 separate lessons. Why do people cope with drugs? What, even, is a drug? What could be some benefits to psychedelics? How do laws affect personal health?

If proponents of this new approach have their way, the conversations will only get deeper, more honest, and resonant from there.

"I think all too often we sell our youth short by not providing them with accurate, scientific information about psychoactive drugs and how to minimize risk," said Gerald Stahler, a professor in the Department of Geography and Urban Studies at Temple University, and an expert in addiction. "There has never been a time when a nation has been completely drug- and alcohol-free—there will unfortunately always be youth who will use psychoactive substances that may cause them and others harm."

According to the DPA, the courses all align with the National Health Education Standards (NHES) and Common Core Learning Standards, and will be available online in at least eight different languages. They'll also be modifiable for, say, teaching in a state, such as Colorado, with legalized cannabis.

"Not only does this curriculum teach students how to stay safe in high school, but it also serves as a foundation to prepare them as they progress into adulthood, where they will inevitably encounter even more drugs," said Sasha Simon, a former health teacher and Safety First's program manager. "Developing an understanding of both the harms and how to reduce them may be the difference in them developing healthy behaviors toward drugs in the long run or not—or even them being able to save their life or not."

Safety First was initially tested out in the classroom at Bard High School Early College in Manhattan in the spring of 2018, before it was brought to an additional five schools in San Francisco later that year. These were admittedly liberal-leaning areas that might be more receptive to these kinds of progressive steps than elsewhere in the country. But the curriculum is basically an expansion of an earlier Safety First program, a research-based strategy designed to aid all parents in speaking to their kids about drugs. The idea was that both Generation X and millennials were struggling to find new, appropriate ways to talk about the dangers of drug use with their children, and how best to handle them, without sounding like some kind of outdated Matthew McConaughey character.

"Some families had questions, but not a single parent I encountered thought any of this was a bad idea," said Drew Miller, the health teacher at Manhattan's Bard High School Early College who participated in the pilot program. "It was pretty much the opposite response. Like, 'Why are only our ninth graders getting this?'"

The dialogue and landscape around drugs has, of course, been changing pretty substantially over the past decade. More and more states this year have legalized recreational cannabis; U.S. cities like Denver have decriminalized psilocybin, the psychoactive ingredient in so-called "magic mushrooms"; and a spate of vaping-related illness—some, though not all, of them linked to black-market THC products—arrived this summer on the heels of what the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) characterized as an epidemic in youth vaping. (While cigarette use among teens has gone down, e-cigarette has skyrocketed.)

But, perhaps most notably, the opioid crisis has hit its peak. This is what the DPA emphasizes above all else: that, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), more than 70,000 people died of drug-related overdoses in 2017, "making it a leading cause of injury-related death in the United States." The Sacklers—the cartoonishly wealthy family that owns Purdue Pharma and helped introduce the country to OxyContin—continue to undergo more and more scrutiny for the role they played in perpetuating this pandemic. (Following a year of lawsuits, the Sacklers have most recently been accused of filing for corporate bankruptcy to avoid responsibility.)

People, in other words, are eager to address the ongoing tragedy in new ways. Like in Philadelphia, where activists have been campaigning, so far successfully, to open up a nonprofit called Safehouse, a safe-injection site where people can do drugs under medical supervision. (It would be the first of its kind in the United States.) The proliferation of deadly fentanyl-tinged opioids has also served to clarify the stakes and the need for dramatic action, instead of preaching abstinence—or a slightly more modern version of drug resistance—into the wind.

"This pattern has persisted into the overdose crisis, which has hit young people especially hard in some jurisdictions," said Leo Beletsky, a professor of law and health sciences at Northeastern University, and drug overdose expert. "This initiative," he continued, "is intended to reframe these education efforts toward information that's most likely to reduce risk, and it's not a moment too soon."

And it's one, Miller said, that the students are "super receptive to."

"I think they just know, really," he continued, "that we're not selling them B.S."

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Alex Norcia on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.