WeWork Is Imploding. More Co-Working Spaces Could Be Next

Credit to Author: Anne Gaviola| Date: Thu, 03 Oct 2019 20:26:31 +0000

The story of WeWork is a cautionary tale of epic proportions. It’s a fiasco of corporate failures, a CEO doing whatever he wanted despite obvious conflicts of interest, and cashing out before his co-working empire came crashing down.

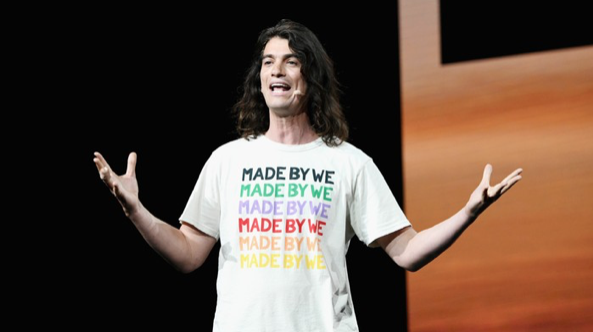

WeWork’s former founding CEO Adam Neumann, described by those in the industry as “messianic” with an “enormous ego,” was everywhere. In 2018, WeWork was reportedly the biggest office tenant in Manhattan, overtaking JP Morgan, the investment bank. During peak WeWork hype, it was valued at US$47 billion. Then documents filed with U.S. regulators pointed to the unsettling concentration of CEO power, and, in less than two months, the company imploded.

According to Ian Lee, associate professor at Carleton University’s Sprott School of Business, “it’s not unusual for entrepreneurs and visionaries to have a big ego, but it’s got to be backed up by a good business model that is ultimately going to create value and make money. WeWork didn’t have that.”

Does this mean that co-working is a bust? Can WeWork-type companies actually make money? Just because Neumann was running a wild show, it doesn’t mean that the whole industry is a sham. In fact, WeWork’s rivals have been building legitimate businesses based on the growing co-working trend, fueled by demand from young digital nomads. But a business expert says this type of company, which leases office space, isn’t all that new, or revolutionary, and competition is fierce. So it’s possible to make money, especially for established players, but it isn’t the cash cow or industry of the future that Neumann made it out to be.

WeWork’s downfall

Even though WeWork is, by most definitions a real estate play, with buildings in more than 120 cities in 35 countries—Neumann pitched it as a new kind of tech firm.

In the S-1 filing, which is the paperwork it needed in order to go public—back when that was the plan—the word “technology” was used 110 times. But just because it called itself tech, doesn’t mean it actually was a tech play. That didn’t stop the notoriously unprofitable company from being valued like a tech company, thanks to its biggest investor, Japanese holding company SoftBank.

For example, Uber and Lyft are fast-growing tech firms which have prioritized growth over profit for years. Both have multi-billion-dollar valuations. Both promise to transform the transportation industry. Analysts who have looked at their numbers have even suggested these companies might never turn a profit. But that doesn’t seem to matter, as long as deep-pocketed investors believe they might someday.

WeWork reported a $1.7 billion loss in 2018 and a loss of $1.4 billion in the first half of this year, and it still pulled off that juicy $47 billion valuation.

Neumann fostered a culture of excess at WeWork, which he referred to as a “community” rather than a “company.” Vanity Fair detailed a 2018 getaway to the English countryside where 8,000 employees took part in an annual event described as “a sort of corporate retreat-meets-Coachella.” Deepak Chopra gave a speech and Lorde was the headliner at the vegetarian “summer camp.”

WeWork had about $2.5 billion in cash in June. In August, the company’s paperwork for its planned Initial Public Offering (IPO)—which would list it on an American stock exchange—revealed that even though it was increasing revenue by more than 100 percent every year, it was burning through cash.

Fast forward to today, and the company is on track to run out of money as early as mid-2020, according to Sanford Bernstein business analysts. This from a company that had raised more than $12 billion since it was founded nine years ago.

Revelations of Neumann using the company as a kind of personal piggy bank suggest a “pathological lack of internal control,” according to John Coffee, director, Center on Corporate Governance at Columbia University Law School. He’s an expert on white collar crime and executives behaving badly.

“The basic pattern was Mr. Neumann regularly either bought or leased buildings and turned around and leased them for a profit to WeWork. Sometimes he denied he was getting a profit but the fact that he was structuring himself as a principal dealing with his own company is a nightmare to anyone concerned with good governance and avoiding conflicts of interest,” he said.

On September 24, Neumann stepped down as CEO, (but not before cashing out $700 million from the company). WeWork announced 5,000 layoffs which are widely believed to include Neumann’s friends and relatives. On Monday, after delaying IPO plans, WeWork announced it wasn’t going to go public after all—IPO plans were shelved indefinitely.

The rise of co-working

The WeWork drama aside, co-working, or so-called “flexible workspaces” are increasingly a thing in the U.S. It’s home to the most flex workspace in the world—80 million square feet of it, which is a lot of real estate. By the end of this year, 696 new co-working spaces are expected to be added in the U.S., and 1,688 globally.

The amount of flexible work space in Canada is up more than 300 percent in the last five years, especially in Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal, according to commercial real estate firm CBRE. In a report released this week, CBRE vice chairman Paul Morassutti said “We haven’t seen a new type of office tenant emerge with such speed and dominance since the dot-com boom.”

Unlike the dot-com bubble, which eventually burst, Morassutti said demand for flexible work spaces will continue although it will likely slow in Canada in the wake of WeWork’s problems.

Around the world, the median age of people using these shared spaces is rising—it was 33 in 2012 and 35 in 2017. The majority are between the ages of 30 and 39.

But as the trend grows, so does the number of companies interested in this commercial real estate.

Lee likens this to the restaurant industry, where failure rates are 60 percent within the first three years. This puts established players at an advantage. “I don’t see the barriers to entry there to keep out other competitors, and buyers have tons of power and tons of choices and there are so many other restaurants trying to cut your throat. And I don’t mean franchises like McDonalds, I mean family-owned restaurants—which have one of the highest failure rates,” he said.

WeWork’s dramatic downfall reminds Lee of the dot-com bubble 20 years ago, where suave CEOs peddled dreams of the future. “You invoke some fancy magical terms from the tech sector but they were never a tech company—just a plain old-fashioned real estate play,” he said. “It’s not a sustainable model. They were buying their growth, they weren’t earning their growth. I’m very skeptical of this space.”

Follow Anne Gaviola on Twitter .