Climate Change Could Erase Human History. These Archivists Are Trying to Save It

Credit to Author: Caroline Haskins| Date: Tue, 17 Sep 2019 16:29:32 +0000

Brooklyn's Green-Wood Cemetery is a giant place of memory.

For one, there’s the gravestones, mausoleums, statues, and stone structures. It’s hard to describe the scale of it. They rise up, respectfully spaced out, on nearly every patch of ground for miles, up and down hills, under trees, unfurling everywhere for 478 acres.

Then there’s the archives. Not every grave at Green-Wood gets an intentional visitor, like a descendent, or a history-lover seeking out a specific name and story. But every grave, every lot, and every person is meticulously documented, and thereby remembered by dozens of paid archivists and volunteers. Everyone buried in Green-Wood has the privilege of being considered a part of capital-H History. If Green-Wood is a city, then the archives are a census for everyone lucky enough to be a resident.

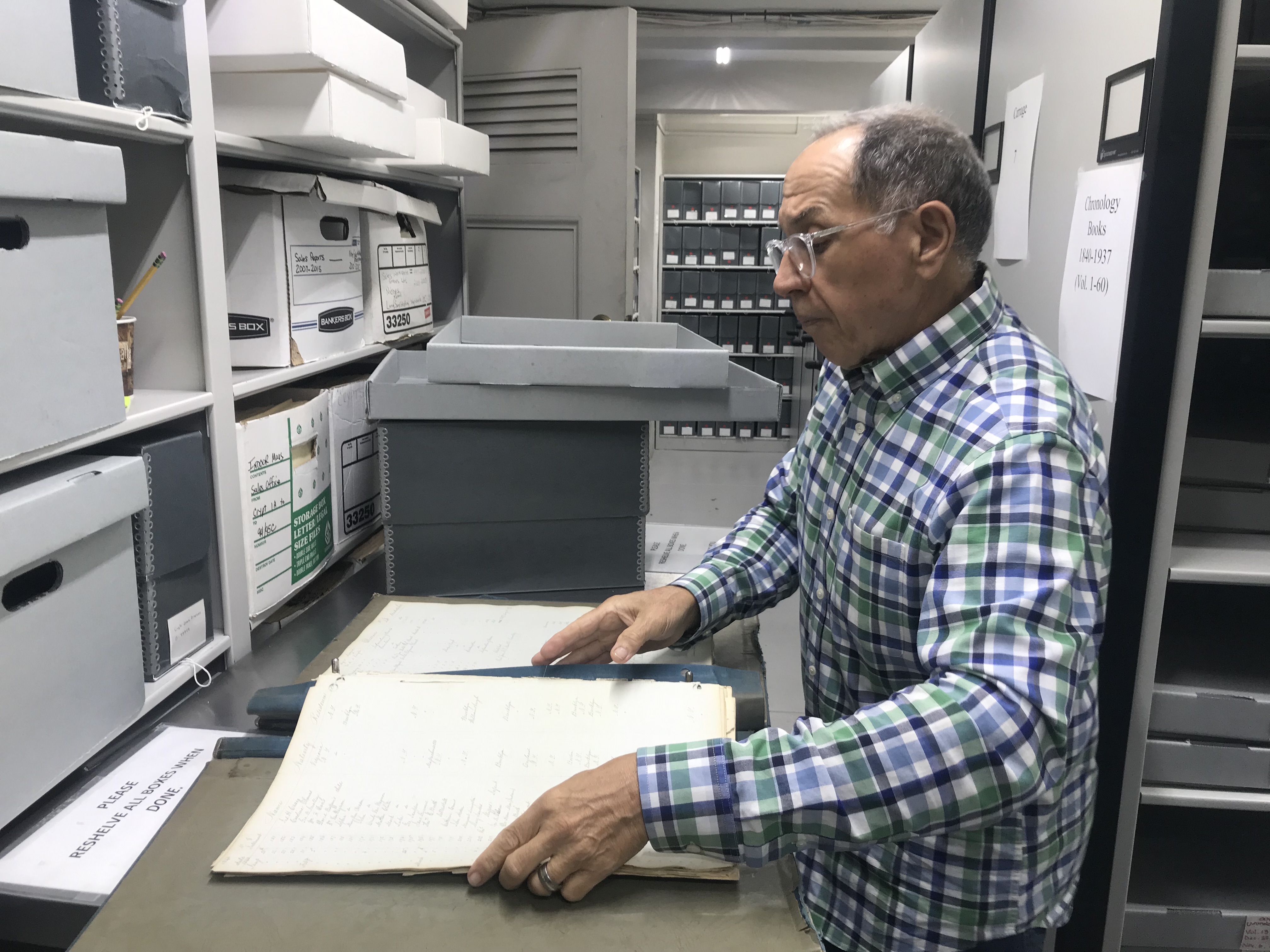

On a rainy day in early September, Green-Wood archivist Tony Cucchiara gave me a tour of the massive Green-Wood archival system, accounting for all 570,000 burials. Green-Wood has millions of pages of burial orders, lot information, and family information spread across three buildings.

Cucchiara explained the information in these files is useful to historians studying disease, to genealogists, and to New York history generally. These records are also useful to descendants of the deceased, to people who want to learn about their families and look for connection.

However, climate change poses long-term and short-term threats to archives around the country. In a worst case scenario, climate change could mean that irreplaceable records documenting the course of human history are lost forever.

Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico in 2017. Most of the island lost power, and people off the island were unable to get in touch with their families and friends. People on the island struggled to get access to food and water. About 3,000 people died both in the immediate violence of the storm and in the aftermath.

The hurricane’s destruction didn’t stop with its assault on human life and livelihood. It also assaulted Puerto Rican culture. Several archives and cultural institutions on the island—including The Archivo General, Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña main offices, the National Gallery, University of Puerto Rico (UPR), the Museum of the Americas, the National Guard Museum, La Casa del Libro, and the Castillo San Cristóbal—were damaged from the storm. Irreplaceable materials were lost.

Art museums, housing delicate paper artifacts, faced a plague of mold and mildew as generators were appropriately allocated to the island's most vulnerable people. As reported by the New York Times, the museum curator had a maintenance crew drill massive holes into the museum walls in order to get some degree of ventilation. The Museum of Puerto Rican Art's sculpture garden lost 90 percent of its collection. Roofs were blown off buildings. Windows were shattered.

Natural disasters have destroyed cultural artifacts before. Earthquakes, for instance, have damaged or destroyed temples and buildings in China, Greece, Puerto Rico, and Japan. However, climate change-driven disasters has made the safety of cultural artifacts into an urgent issue. In the past few years, Hurricane Sandy, Hurricane Harvey, and Hurricane Irma have damaged dozens of museums and cultural centers in New York City, Houston, Florida, and the Caribbean. This isn’t just bad luck. Because of climate change, hurricanes are happening more frequently. And since human culture is disportionately centered on coastlines, cultural repositories are at risk.

We’re not just in the midst of a climate crisis. We’re in the midst of a cultural reckoning. Politicians are debating how or if we should adapt for the future, with responses ranging from calls for a sweeping Green New Deal, to calls for “realistic,” lightweight regulation on polluting titans, to outright climate denial. Meanwhile, something else is going on. Archivists and conservators are taking stock of human culture. They’re asking, what do we have, and what could we lose in the next 100 years? Is there any way to save what’s at risk?

This problem prompted archivists Eira Tansey, Ben Goldman, and Whitney Ray to complete the Repository Data Project, a growing database that currently catalogs more than 25,000 archives in the United States, including major university libraries, small museums, corporate archives, and art facilities.

The reason for making this database, Tansey told Motherboard, is to figure out which facilities are at risk of sea level rise and worsened storm surges over the next 100 years. If we know what’s at risk, theoretically, we can plan and prepare for the worst. Or alternatively, we can at least know which facilities need help when the next disaster strikes.

The study brought up an uncomfortable question. What happens if we abandon culturally rich areas? What will happen to the archives in these areas, to the history stored in them?

“As there will be inevitable migration and abandonment of certain areas, the only traces that will be left of some places is in the archives,” Tansey said. “And so, we have a large amount of responsibility for what it looks like to do our work in the context of climate change.”

But of course, the Repository Data Project isn’t just about archivists taking cultural stock. The project, at its core, forces us to ask difficult questions. In a changing world, one where climate change will change the way coastlines look and likely the way governments function in upcoming decades, who and what will we choose to remember?

Some archivists are organizing teach-ins for people to learn about how to protect their histories. Archivists are taking millions of records, and one by one, putting them in folders and vaults designed to withstand the worst conditions a warming world will bring. Archivists are starting to realize that we need to adapt to a changing world, because our cultural memory is at stake.

Why Do We Archive?

The creation of records is a fundamentally political act.

We archive music recordings and films. We archive flyers, pamphlets, books, newspapers, and images from social movements like the civil rights movement, feminist activism, LGBTQ+ organizing, and the labor movement. Records have the opportunity to represent the lives, stories, and histories of historically marginalized communities not protected by their governments or society at large.

“Even if you never step foot in an archive, you benefit from archives,” Tansey said. “Because places like the National Archives hold tons of records that document people's rights and their own histories.”

We also produce birth records, photographs, newspapers, books, letters, advertisements, registrations, lists, memorandums, and death records. But we don’t do this just for the hell of it. The U.S. has a long history of slavery and colonialism, and these organizations rely upon bureaucracy and paper-pushing.

Slave logs were used to dehumanize enslaved people and convert them from people to cargo. Census records, among other things, were used to help the U.S. government track down Japanese-Americans and place them in internment camps.

So what do we communicate when we preserve records? Sometimes, the knowledge in records is useful because the governments and corporations will need those records in the future. Other times, we say that the knowledge in those records could be useful in the future. We say that the communities represented in those records matter and have a place in our collective memory.

The world isn't going to blow to smithereens in 11 years. (This viral conclusion from a recent climate change report is just factually wrong.) But the UN’s committee of climate scientists, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, said in October that we will need to fundamentally and restructure our governments and global economic system if we want to avoid an absolute worst-case warming scenario.

As climate change warms the Earth, it also warms our oceans. Since warm oceans power storm systems like hurricanes and typhoons, climate change has brought more frequent hurricanes, and hurricanes that are more severe on average. Now consider the fact that storms have been getting slower, on average, for the past 70 years. The longer that a storm is centered on an area, the more time the storm has to incur wind and flooding damage. Basically, worse storms are happening more often.

Human culture is often stored in at-risk areas. According to the UN, 40 percent of the world's population lives within 60 miles of a coastline, and about 10 percent of the world's population lives in coastal areas that are less than 10 meters above sea level. Additionally, out of all cities with populations over five million, two thirds of them in coastal areas are at risk of inundation due to sea level rise.

When climate change-fueled storms damage archive buildings, wind, water, and abrupt humidity can quickly damage invaluable records beyond repair. Even the most well-funded facilities are at risk of storm-driven damage, especially if they’re in coastal areas.

Regional and local facilities, which tend to have less robust funding than federally funded facilities or major research institutions, are at an even higher risk. Hurricane Katrina, damaged countless local records for people living along the Gulf Coast. “Property deeds, birth certificates, and personal papers, as well as records documenting rights and entitlements, such as Social Security and veterans' benefits" were damaged on a massive scale. Cultural artifacts, botanic gardens, museums, and historic locations throughout the Gulf Coast were also damaged.

Archives and cultural centers face long-term risks because of climate change, completely independent of extreme events like hurricanes. Climate change is making the world hotter and more humid, on average, and heat and humidity are precisely the conditions that put delicate paper documents and art at risk.

Responding and adapting to climate change forces us to ask what we owe to each other. We have to confront which communities we are willing to protect, whether we are willing to make reparations for past injustices, and whether we have the potential to build a better world than the one that got us into this mess. How can we build a better world if we don’t have the history of the world we come from?

The Repository Data Project

The “US Archival Repository Location Data” project—“Repo data” project, for short—lives on the website of the Open Science Foundation, where academics and researchers can easily share their findings publicly. According to a state summary sheet, the Repo data project has documented the existence of 25,771 archives at 18,614 addresses. The data is also posted on GitHub.

Eira Tansey, one of the two principal investigators of the Repo Data project alongside Ben Goldman, said the project began with a grant from the Society of American Archivists, and their goal was simple: document the existence of as many archives in the U.S. as possible. Ironically, although the job of professional archivists is to catalog and store data, there was no comprehensive list or data set of all U.S. archives until this project.

“It’s not like hospitals—we know every hospital in the United States because they’re highly regulated,” Tansey said. “No such thing exists for archives.”

Tansey and Goldman hired then-graduate student Whitney Ray in 2017 to help with the project. The team reached out to about 150 regional archive associations and asked them to send any records they had listing archives in their field. Tansey said that this work collectively took from mid-2017 through the early months of 2019.

A large part of the Repo Data project was determining what exactly counts as an archive.

“There are a lot of people where when they think of archives, they think, ‘OK, it’s a very protective space where you go and you put on white gloves, and you have to be a historian that has a good reason to go through these things,’” Tansey told Motherboard. “But if we think of archival records as being things that document people’s daily lives, then maybe they exist in places like public libraries, or small town halls, or places that we don’t necessarily think of as archives.”

Tansey and Goldman also collaborated with Penn State University geographer Tara Mazurczyk and PSU librarian Nathan Piekielek to assess how these archives would be impacted by climate change. Their paper, which was published in the journal Climate Risk Management in 2018, found that climate change posts a severe risk to archives.

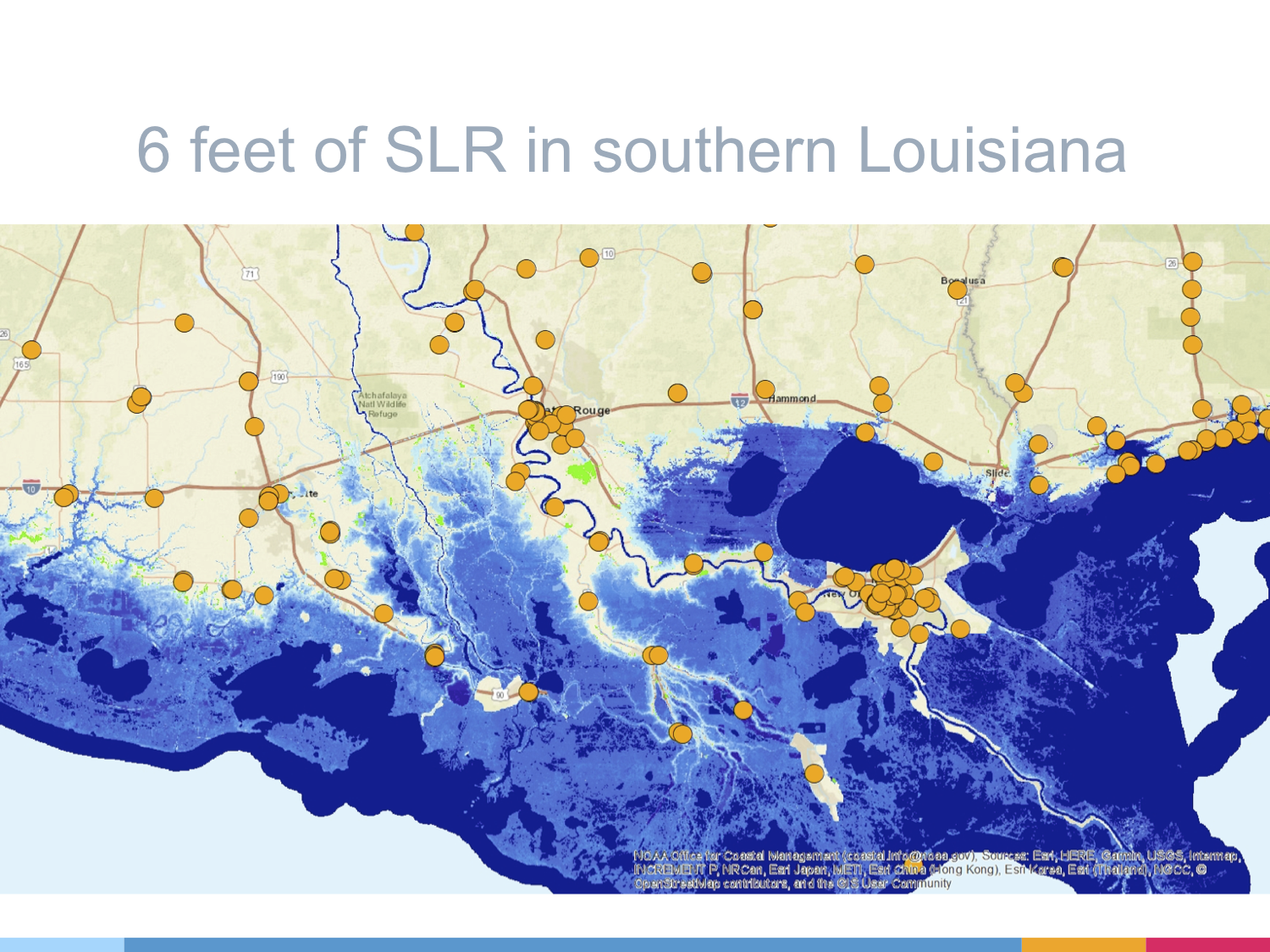

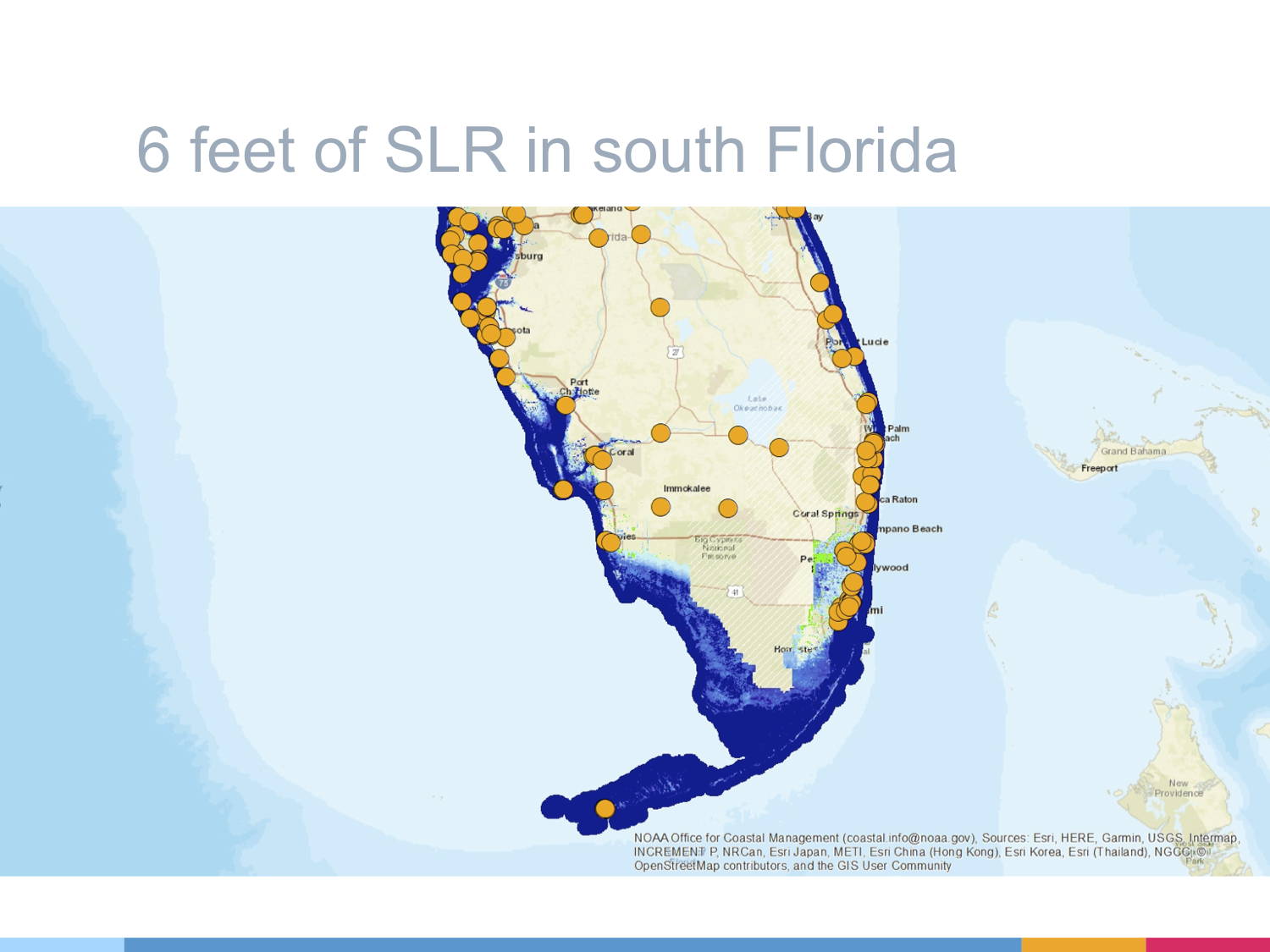

According to the study, 98.8 percent of archives are likely to be affected by at least one climate risk factor, such as sea level rise, storm surge, flooding, increased rain, warmer temperatures, or humidity. The researchers assessed conditions in a “business as usual” scenario, assuming that we collectively do little to nothing to mitigate climate change. The finer details of the findings were grim:

- 18 coastal locations would be completely flooded with a 1.8-meter rise in sea level.

- 84 coastal locations would go underwater with a direct hit from a category 4 storm.

- 92 coastal locations could warm 10 degrees Fahrenheit or more by 2100

- 93 coastal locations could get an additional 10 inches of rain each year by 2100, compared to today.

“There are going to be some places where it won’t be possible to live anymore—or, if people do live in them, then we will have a very different relationship with what it looks like,” Tansey said. “In some places, the only documentary traces left will be in archives.”

This isn’t a far-off concern. As the Repo Data Project team was cataloging U.S. archives, Hurricane Irma struck Florida and the Caribbean. Fletcher Durant, head of conservation and preservation at the University of Florida, asked the team for its list of archives in Florida. Durant was volunteering for the American Institute for Conservation’s National Heritage Responders, which gives archives resources in the wake of disasters like hurricanes.

“We actually called over 500 organizations in the state of Florida,” Durant said. “If they had collections that were damaged and needed conservation assistance, of if they wanted assistance working through the FEMA paperwork, we could put them in touch with FEMA folks that might help them.”

Durant said that of the 500 archives they contacted, thankfully, only 18 of them reported any damage to their collection. They reported leaking roofs, broken windows, and fallen trees, which compromised the climatic conditions inside the facilities and put paper materials at risk of water damage.

Since Irma, Florida has been hit by three tropical storms and two hurricanes, Michael and Dorian. This is going to keep happening. Archives in Florida, and coastal regions generally, will get wetter, more battered, and more humid. It’s not a matter of whether records are going to get lost. It’s a matter of which records will get lost, and whether we know they’ve been lost.

Intuitively, one might think that a solution to mitigating the risks that climate change poses to archives is simple: just digitize the archives. But digital archives face a host of threats. Accidental server crashes have temporarily wiped data stored in digital archives, authoritarian regimes have wiped digital archives on a whim. And theoretically, water damage could damage sensitive servers that store digital records.

Archivists also have to maintain the digital archive in addition to maintaining the physical archive. Digital archives aren’t a replacement for physical documents, photos, or paintings. They’re just an additional way of storing them.

Tansey argues that digitization is one strategy, but it’s not a complete solution. Plainly, she said, it’s expensive to scan, upload, and describe records so that they’re searchable in catalogs. Digital archives also have to be maintained, just like physical archives. What happens if the community relevant to an archive is forced to relocate?

“Let’s say you have a city that effectively, over the next 100 years, becomes abandoned, Tansey said. “There’s no more tax base. Who is now responsible for maintaining the records of that city that no longer exists? Even if you can digitize them, someone still has to pay for domain registration. Someone still has to pay the storage costs of keeping those records as accessible files. And PDFs are great now, but what’s the file format going to be 100 years from now?”

A Day at Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery Archives

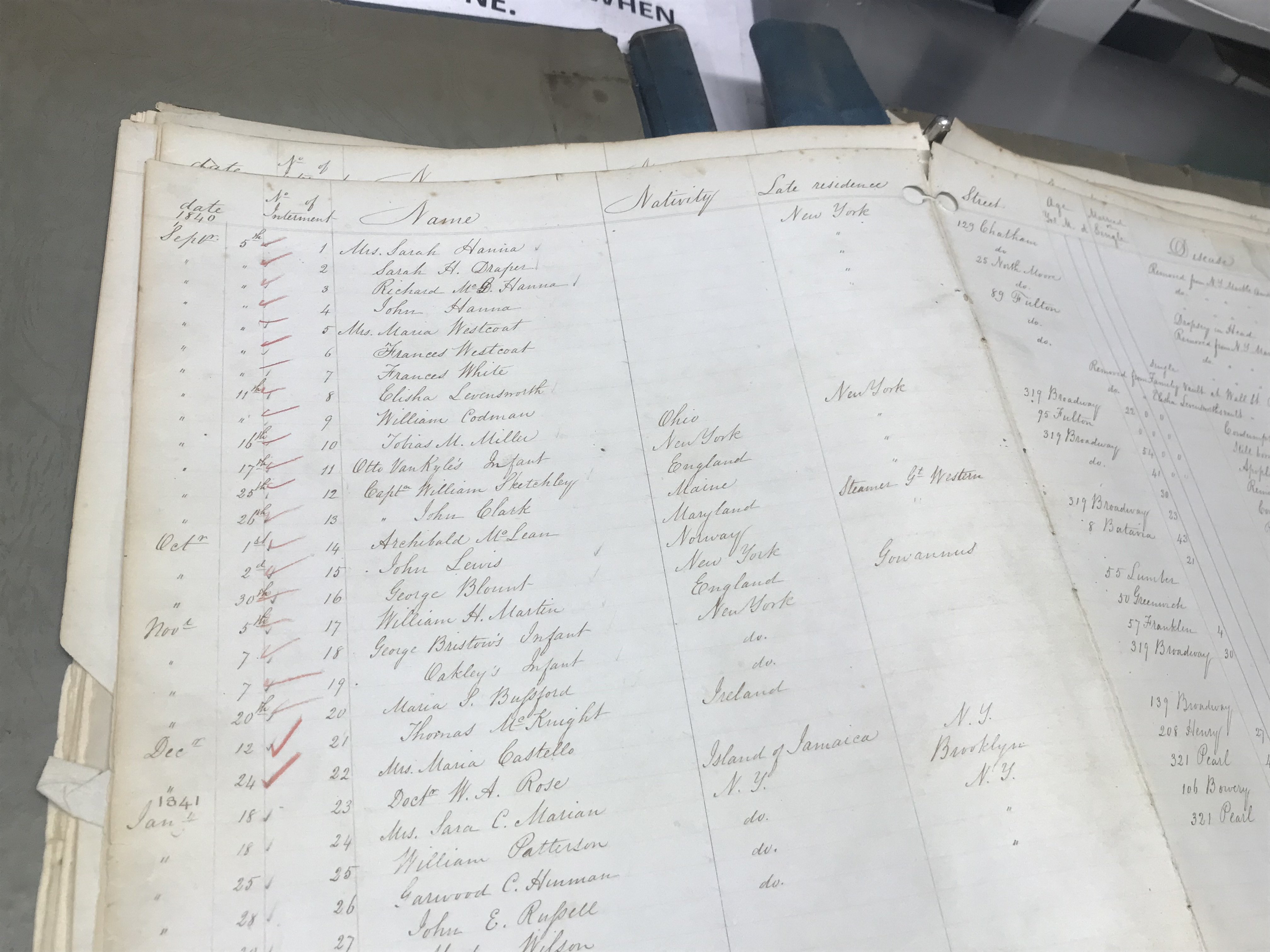

Green-Wood Cemetery buried its first person in 1840. About 47,000 people lived in Brooklyn at the time. Now, Green-Wood is populated by about half-a-million, all dead. The people who work there eagerly refer to the dead as the cemetery’s “permanent residents.”

The job of Green-Wood Cemetery archivist Cucchiara is to work with on-staff archivists and volunteers to accomplish three things: minimize the speed at which materials deteriorate, make those materials accessible to researchers, and eventually, at some point in the future, digitize those records and make them all public.

He also oversees a group of volunteers who, for the past 10 years, has been working on “rehousing” documents from regular paper folders to alkaline, acid-free folders.

“We have a very intrepid group of volunteers that come in on Sundays about every six weeks, and they work for five to six hours straight,” Cucchiara said. “20 to 25 people, opening folding and unfolding and flattening these materials. It takes a lot of effort to do this. This is all hand work, that’s the only way we can do it.”

Cucchiara said the volunteers are generally graduate students and retirees. “They’re actuaries, they’re attorneys, they’re chemists, they’re teachers, who in their retirement, have a great interest in and love of history,” he said.

The work of these volunteers is dramatically extending the lifetime of these documents. Common materials can often destroy sensitive documents. For instance, regular folders and rubber bands are often acidic. When acid migrates from paper to paper, the documents deteriorate quickly. Metal paper clips can also rust on paper sheets, and scotch tape is impossible to remove without damaging the document.

So lot by lot, cabinet by cabinet, floor to ceiling, these workers have rehoused millions of documents from acidic danger to alkaline safety. There’s two main “groups” of archival records at Green-Wood: the lot burial orders, and the chronology books.

Burial orders pertain to what’s in a “lot,” or a patch of grass that could house dozens to thousands of graves. These lots are either private (and expensive) or public (and more densely packed). The lot burial orders contain highly specific information about each person in a burial spot, like cause of death, when they died, age, whether they were married or single, and even the addresses of family members, businesses with which they were associated. If it’s a private lot, which were expensive even at the turn of the century, there might even be even drawings and diagrams of the lot in question.

The chronology books, meanwhile, consist of 60 volumes of extra large pizza box-sized books documenting the burial of every single person from 1840 to 1937. These books also include individual information like place of birth and cause of death.

This information is valuable, but maintaining it all is incredibly expensive. Sets of acid-free document cases can cost hundreds of dollars. 100-packs of alkaline folders cost about $30. Plastic paper clips cost more than metal paper clips. Green-Wood also uses 13 mobile storage “carriages.” These costs add up quickly when you’re dealing with millions of pages of records. Eventually digitizing the records and making them searchable online, Cucchiara said, will cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. He emphasized that digitization won’t occur until far into the future.

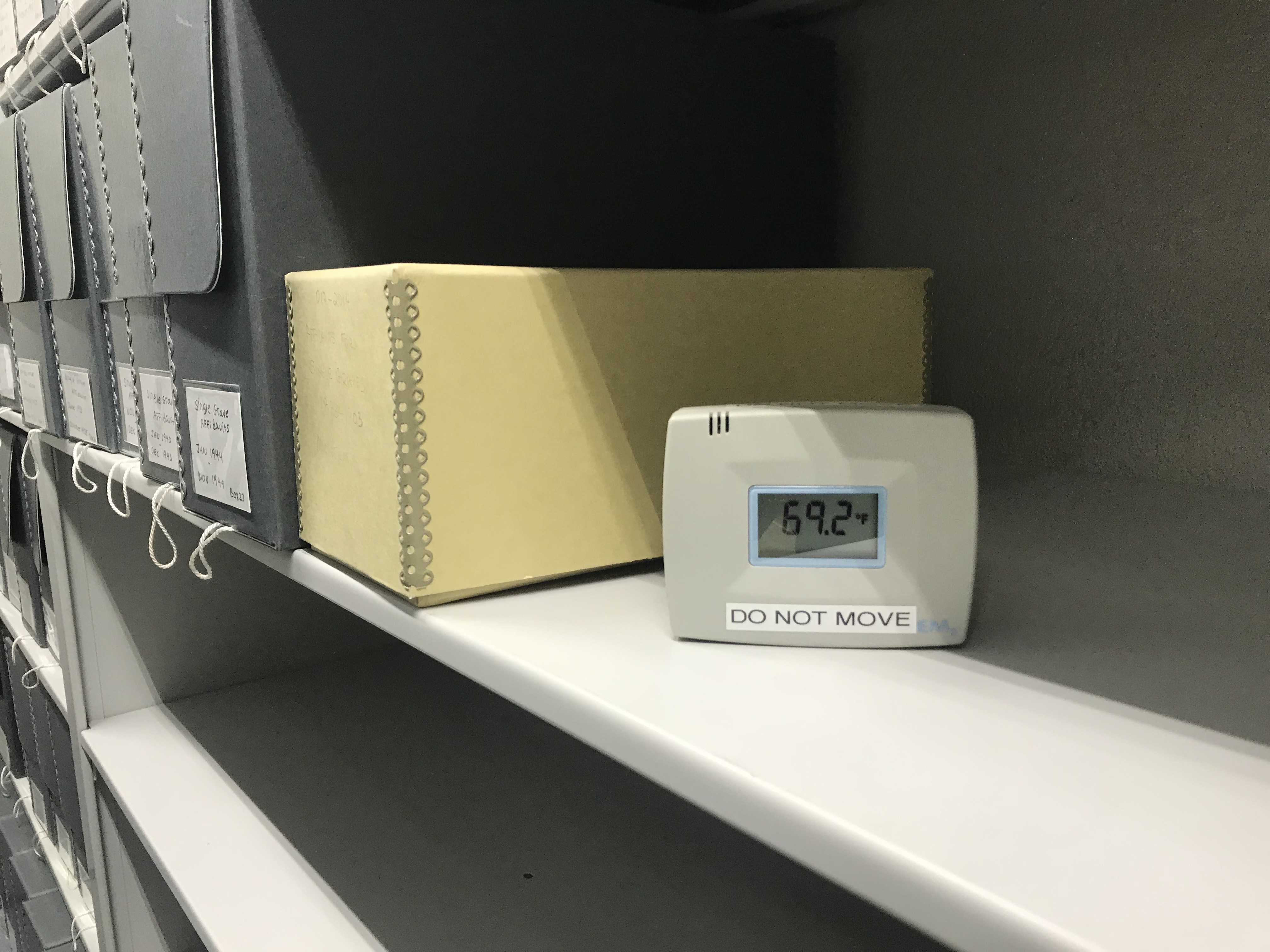

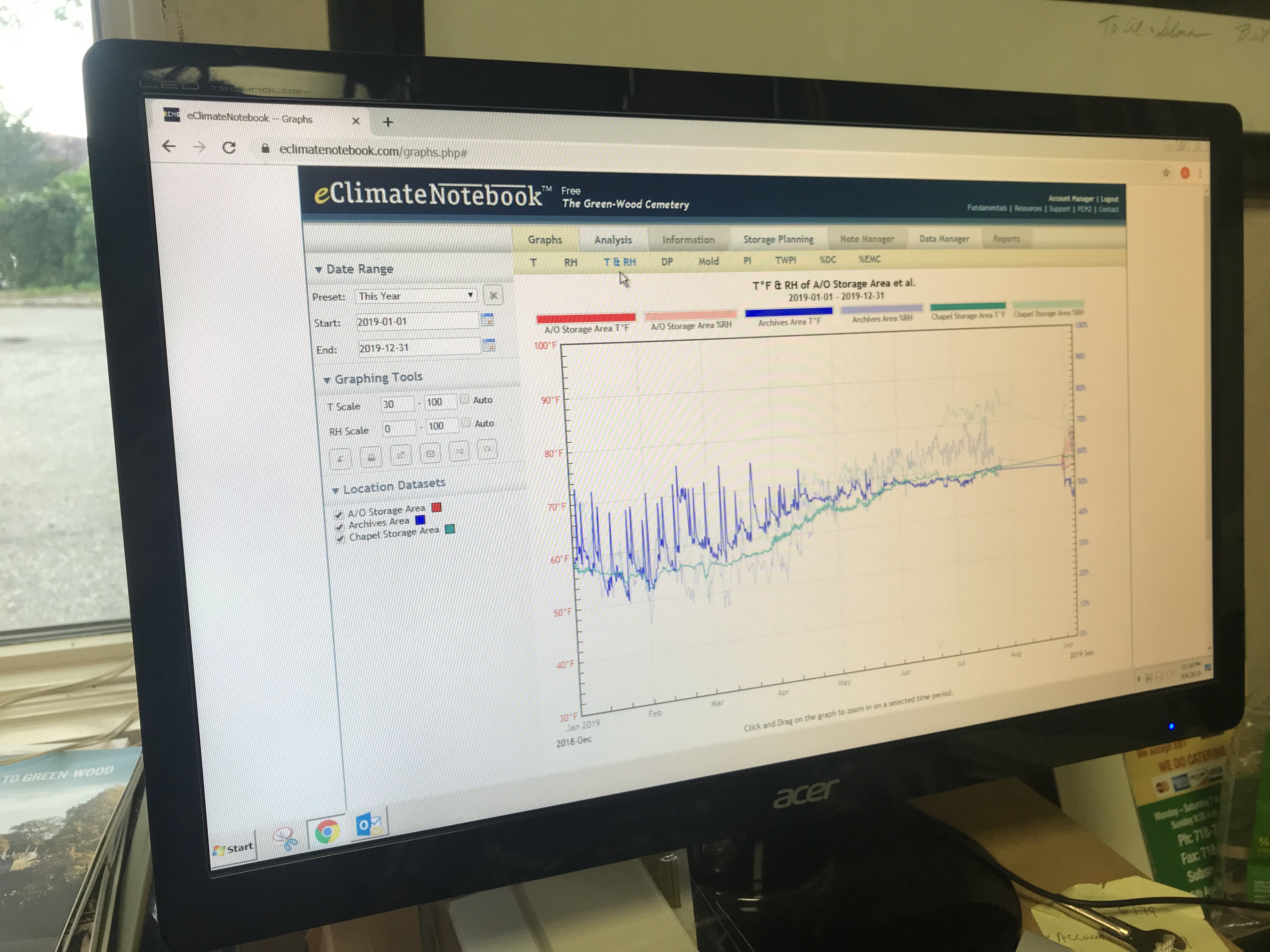

Probably the least expensive way that Green-Wood protects its documents is through constant monitoring the temperature and humidity in the places the archives are stored. Once a week, Cucchiara said, he retrieves the monitors and uploads the information to a database, which tracks changes in the facilities over time. Cucchiara said that both the database and the monitors are inexpensive.

The charts are remarkably consistent. The only blips in temperature were in the middle of the winter. Cucchiara explained that the archivers would turn up the temperature a few degrees so they could work with the documents comfortably.

Green-Wood Cemetery in a Changing Climate

There’s a divide within Green-Wood. On one hand, there’s the heavy stones above ground and the metal caskets below ground. They’re built to withstand rain, wind, heat, snow, flooding, and ice. These are supposed to be durable monuments to memory. And on the other hand, there’s the paper archives. Millions of volumes of incredibly delicate paper records, stored in expensive alkaline folders in climate-controlled faults, and handled delicately. These are the fragile monuments to memory.

But it was the outdoor structures, the durable monuments to memory, that were damaged during Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Cucchiara said that the archives, which would have become moldy and unreadable if they touched floodwater, were unharmed. There were no broken windows, no damaged roofs, nothing. The facilities didn’t even lose power.

Cemeteries were conceived as a way of separating and containing the dead. But they’ve never aimed to forget the dead. That’s why cemeteries have stone monuments and metal caskets designed to last multiple generations. One day, maybe when humans are dead and gone, we’ll have a layer of the Earth’s crust that’s embedded with cemetery stone and metal. Maybe, in this human-layer of the Earth, we’ll have gravestones torn apart by climate change-fueled superstorms, alongside AirPods, plastic, and everything else that capitalism has managed to make but not destroy.

But even a broken cemetery monument is a privilege for the few, the likes of turn-of-the-century New York elites and their descendants. Being in a paper archive, likewise, is a privilege. It’s a ticket into cultural memory. But not everyone is afforded that privilege.

Consider the loss of records that occurred after Hurricane Katrina: Thousands of living people experienced “identity loss” when their personal documents were destroyed. Photographs, films, paintings, and historical documents in homes and museums, testaments to the history of the people who have lived on the Gulf Coast, were destroyed. People living in the Gulf region have just as much of a right to be remembered as the people of Green-Wood. But there’s a social and economic barrier of entry to visibility that not everyone can pass.

The Future of Archives

At the time of writing, Hurricane Dorian is winding down after ravaging the Bahamas and barreling up the east coast of the United States. The Bahamas, from what we know now, have been devastated. An estimated 15,000 people don’t have food or shelter. Many lives have clearly been lost, but we don’t know how many. Entire cities have been flooded and leveled, but we don’t have a precise sense of what’s been lost and what’s left.

Climate change is not a distant threat, or an abstract. It’s killing people right now. It’s devastating communities and destroying human culture right now.

Tansey said that going forward, the goal of the Repo Data Project is to make it as robust as possible, as inclusive as possible, and as up-to-date as possible. The team already used the grant provided by the Society of American Archivists, so right now, a priority is finding a financial pathway to maintaining stewardship over the data.

In August, Tansey and co-principal investigator Ben Goldman were honored by the Society of American Archivists for their work on the project.

Around the same time the Repo Data Project got started, in early 2017, Tansey became involved with a decentralized collective called Project ARCC (Archivists Responding to Climate Change). The group hasn’t been consistently active since it was created. But on September 20, the same day as the Global Climate Strike, the group is co-hosting two teach-ins in—one in Austin, Texas and one in Vancouver, British Columbia—with Archivists Against History Repeating Itself, a collective whose mission is to use archives to “address” and “repair” injustice perpetrated by “white supremacy, colonialism, patriarchy, heteronormativity, ableism, and capitalism.”

“These Teach Ins will provide insights and serve as a launching point for future actions against climate change,” the event description says. “By joining international efforts to raise awareness of climate change, archivists can join the global community to tell leaders across the world that we demand climate action.”

As for Green-Wood, it’s unclear what a changing climate will mean for its yellow and purple wildflowers, cooing crickets, and grass cut down to a height of exactly three inches by a landscaping staff. Green-Wood will certainly continue to receive money to maintain its living plants and the papers of the dead. Maybe the cemetery vegetation will wither in climate change-driven heat, or be blown apart by future superstorms. The papers, meanwhile, will probably last as long as the community that it represents continues to exist. Maybe in a couple centuries or millennia, Brooklyners will retreat or die off, and Brooklyn as we know it ceases to exist. Maybe then, the papers will drop into the earth and feed a city of worms.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.