The Composer of Kingdom Hearts Has Never Stopped Reinventing Herself

Credit to Author: Sam Goldner| Date: Fri, 06 Sep 2019 20:07:32 +0000

The first time I encountered Yoko Shimomura was in 2017 at a crowded concert hall in downtown Tokyo. It was the opening night of the Kingdom Hearts Orchestra’s first ever world tour, and all around me, jittery Square Enix fans clutched their newly purchased tour-exclusive merchandise and prepared to collectively cry along to “Dearly Beloved.” Partway through the show, Tetsuya Nomura stepped out onto the stage wearing an outfit as flamboyant as a character from one of his games (complete with tattered shorts, a black sports jacket, and swooshed hair), standing triumphantly onthe stage like the rock star he obviously is. But when Yoko Shimomura—the one actually responsible for composing all the music we were there to hear that night—finally emerged onstage, she appeared as mild-mannered and modest as a high school piano teacher, even as fans welcomed her with rapturous applause.

Shimomura carries this unassuming attitude about her entire body of work, even as she’s earned a worldwide reputation for composing some of the most vibrant and celebrated scores in video game history. Looking at her resume is like taking a tour through the evolution of the home console: Her early days at Capcom saw her forging the colorful, heart-pumping themes of Street Fighter II. Working with Square, her zany melodies served as the backbone for Super Mario RPG (as well as the ensuing Mario & Luigi series). And that’s to say nothing of her soundtracks for Kingdom Hearts and Final Fantasy XV, which have taken her work into an entirely new stratosphere of popularity, combining her background in Romantic classical music with her affinity for concocting dreamy, heartfelt arrangements.

“No matter what form it takes, I always want a song I create to move people’s hearts,” Shimomura tells me via email. But from our conversation, I get the impression that she doesn’t quite realize the extent to which her work has impacted not only video games, but the larger world of music as a whole. Shimomura’s soundtracks have traveled far and wide, serving as an inspiration (and often as literal sample material) for artists in both the upper echelons of popular culture as well as in the deep experimental underground. She’s turned up in songs by mainstream R&B artists, been sampled on posthumous hip-hop releases, appeared on tracks from the British club circuit, and even received nods on left-field vaporwave releases. “I have heard directly from foreign artists who have listened to and been raised by my music,” she tells me with a sense of shock. “I still can’t believe it myself, but it’s a tremendous honor.”

Although Shimomura’s work itself has crossed countless musical boundaries, her background is about as traditional as it gets. Born in Hyōgo to a family that encouraged her to study piano since grade school, Shimomura was raised on Romantic composers like Chopin and Rachmaninoff, drawing particular influence from the more minimal piano works of Ravel and Debussy (one can even hear echoes of Erik Satie in her gentle Kingdom Hearts ballads). This classical sensibility has carried throughout her many projects, though Shimomura herself doesn’t have any reservations about crossing over from the classical world into soundtracking arcade games.

“Personally, I don’t put classical music on a high pedestal myself,” she says. “I think all music genres are created equal. Music is meant to touch people’s hearts, so if there is a piece of music that does just that, then I think it should be considered wonderful music that is neither above nor below anything else. Hundreds of years from now, game music might be revered the way classical music is today.”

Shimomura never originally intended to work in video games, however upon receiving her first job offer out of college from Capcom, she began to apply her classically trained chops toward compositions for three sound channels on the NES (including, ironically, the Disney-themed NES platformer Adventures in the Magic Kingdom, securing her credentials with the House of Mouse right from the jump). Her first major breakthrough came in 1991 with Street Fighter II, which demonstrated Shimomura’s knack for writing complex, upbeat melodies that combine ornate arrangements with a sense of humor. Filled with fist-pumping, zig-zagging themes representative of each characters’ home country—from Ken’s bleeding heart American hair metal to Chun-Li’s cascading Chinese scales to Blanka’s mutant Brazilian jungle funk —Street Fighter II was an international smash hit that brought Shimomura’s eccentric melodies across the world, leaving a particularly strong impression amongst Western producers raised on arcade games.

Excerpts from the Street Fighter II soundtrack have popped up all over the place. Chun-Li’s theme turns up as the leading sample for British grime heavyweight Dizzee Rascal’s “Street Fighter” instrumental. A piece of Blanka’s theme appears three minutes into acid house DJ A Guy Called Gerald’s lo-fi jungle track “Cybergen.” Even Kanye West turned Street Fighter II’s classic “perfect” sign-off into his own personal signature. And that’s not counting the dozens of other recorded instances where the game’s snappy sound effects have been sampled by rappers, producers, and experimental musicians including 21 Savage, Death Grips, and Flying Lotus, just to name a few.

Although Capcom’s side-scrollers may have delivered Shimomura her first huge success, it wasn’t until she joined Square in 1993 that Shimomura found her true home: JRPGs. Square had already established themselves as gaming heavyweights at that point when it came to building immersive in-game worlds, in large part thanks to the radiant work of composers like Nobuo Uematsu and Koichi Sugiyama. While Uematsu had made a name for himself by injecting his sweeping Final Fantasy scores with and epic dose of prog rock, it was Sugiyama who truly set the precedent for Shimomura’s classical style to flourish at Square with his work on the Dragon Quest series, which saw him applying his background as a professional orchestrator to bring a symphonic sensibility to the world of video game music (unfortunately in the years since, Sugiyama has become a contentious figure in gaming due to his outspoken nationalism and ugly comments toward the LGBTQ community).

While at Square, Shimomura took on a number of projects that pushed her music to strange new places; games like Super Mario RPG had her taking her manic battle themes in even wackier directions than before, while titles like Legend of Mana let her flex her Romantic leanings to build lush, intricate fantasy worlds. The latter soundtrack has produced several particularly curious samples from hugely popular artists, including none other than Janet Jackson and XXXTentacion. In Jackson’s case, her 2001 song “China Love” appears to feature a sped-up sample of the song “Moonlight City Roa” from Legend of Mana. Although there are no official online records verifying this sample, when I sped up Shimomura’s track by about 10% and compared it to Jackson’s song, it sounded exactly the same (“Janet Jackson!?,” Shimomura says in disbelief when I inform her of the sample. “I’ve never actually heard this before. There’s got to be some sort of mistake!”)

The XXXTentacion connection, on the other hand, is even more bizarre. Recently, the late rapper’s label announced a new anniversary edition of his final album that opens with a “tribute” to XXXTentacion supposedly penned by Shimomura herself. Upon digging deeper, it seems that the tribute in question actually just a slowed-down track from Legend of Mana, making the question of whether Shimomura actually authorized this sample—or if she even knows about XXXTentacion and his publicly known history of domestic violence—all the more ambiguous (Shimomura wasn’t able to comment on the matter as our interview took place before this tribute album was announced). But it wouldn’t be the first time XXXTentacion has used Shimomura’s music as sample material, which just goes to show how far her influence has traveled over the years both inside the gaming world and out.

“Shimomura’s style really centers around the piano, regardless of what instrumentation she’s working with,” says Celeste soundtrack composer Lena Raine, who’s released plenty of her own music that treads the line between ambient, electronic music, and pop. “But there’s also a really strong rhythmic component to it. She really excels when it comes to providing motivation for continuous action sequences. She writes music to dance to, and that’s something I always try to strive for.”

Nowhere is this more apparent than in her apocalyptic Parasite Eve score, which sees Shimomura infusing her usual mixture of twisting melodies and high-adrenaline battle music with a sinister dose of hardcore jungle and techno. “Primal Eyes” alone manages to fit nu-metal riffs and an operatic piano lead into its non-stop barrage of breakbeats and wraithlike vocals, coming out with something that wouldn’t sound out of place on an album by warehouse rave overlord Machine Girl. Shimomura even stepped outside the normal protocol for how video game soundtracks are released with Parasite Eve; rather than opting for an orchestral arrangement of the game’s score to release on CD (as is common with supplemental video game music), Shimomura had the idea to commission an album of club-style remixes, transforming the game’s grimy urban sound into a full-on explosion of drum ‘n’ bass and house music.

“I really owe a lot to her work on Parasite Eve back in 1998,” says Raine. “When Parasite Eve released, the combination of electric guitar, synths, and piano really opened my eyes to a completely different style of scoring. That, combined with the release of the Parasite Eve Remixes album, really opened my eyes to artists like The Prodigy, Chemical Brothers, Aphex Twin, etc.”

Funny enough, Shimomura herself appears to have zero interest in the world of warehouse raves. “I wouldn’t say I’m a big fan of techno music,” she says. “I don’t go to clubs, either. I think the opportunity came up because by that point, I was using synthesized audio. I wanted to try increasing the number of tracks, and to arrange the music in a cool way.” But even if she’s not personally tapped into the scenes that her soundtracks manage to evoke so well, her work for Square has undeniably made an impact on underground electronic artists around the world (her Super Mario RPG score even serves as the opening theme for a cult favorite grocery-store-themed vaporwave album).

“I wouldn’t be surprised to hear these Parasite Eve tracks at a rave; they would stand out as some of the most futuristic and bizarre jams within a playlist of contemporary beat music for sure,” says Max Allison, who runs the Chicago D.I.Y. label Hausu Mountain along with recording his own frenzied style of video-game-inspired electronic music as Mukqs. He notes with particular enthusiasm his love of Yoko Shimomura’s ability to wrench intricate, evocative themes and sounds out of extremely limited hardware: “Among SNES games, the arrangements for both the CPS1 and CPS2 versions of the Street Fighter II soundtrack pack so much power in the drum programming and instrumentation. You can hear Shimomura’s ear for orchestral arrangements starting to shine through, which she would explore more in-depth on later OSTs, but the little bite-sized one-minute loops here are all perfect and present so many discrete ideas in so little time.”

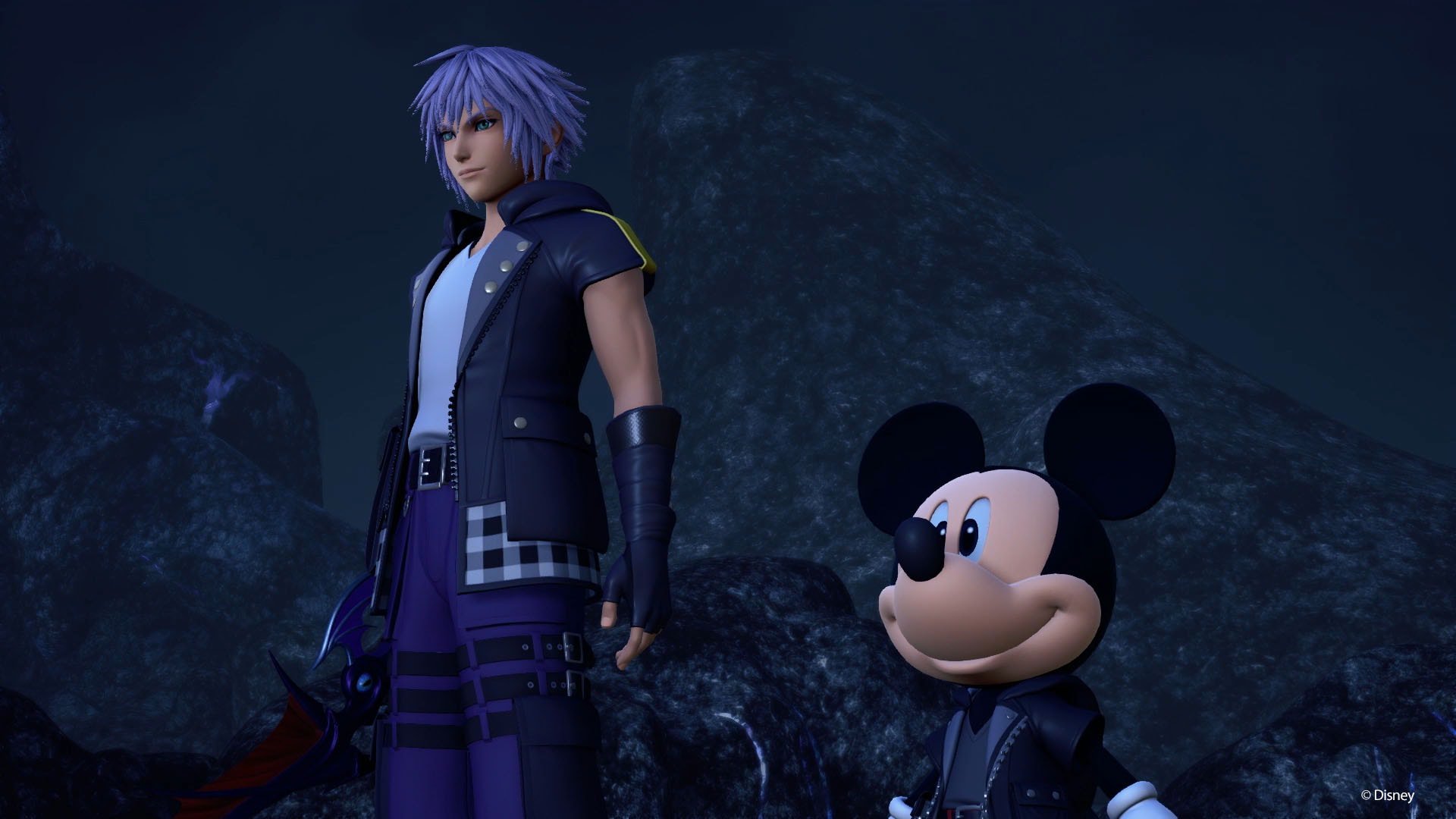

While much of Shimomura’s earlier work has become synonymous with the 16-bit era, the classical nature of her style has only become even more apparent as console technology has evolved. In 2002, after almost a decade of working alongside Shimomura, Square Enix released the debut installment of Kingdom Hearts, which saw Shimomura taking the company’s flagship Final Fantasy series in a more theatrical direction befitting of its whimsical Disney backdrop. “I personally find the Disney universe to be very charming,” Shimomura tells me when I ask about her relationship with the animation giant. “I think my music has turned out to be a good fit with the universe because I compose the tracks believing they will. If they weren’t, the songs would be rejected.”

The music of Kingdom Hearts is filled with fantastical orchestrations and cheerful melodies that evoke Disney’s bright colors and kid-friendly locales, but a huge part of what’s given it its enduring magic is how surprisingly dark Shimomura’s score is. The series’ beginning moments are its most surreal; after opening with Utada Hikaru’s instantly iconic “Simple and Clean” (which, incidentally, I have seen absolutely pop off at raves at 3:00am), players take their first steps to “Dive into the Heart,” an eerie Gregorian chant that gives the game’s Disney Princess purgatory of a tutorial a looming and enigmatic sense of dread. This gloomy feeling of lost innocence carries throughout the whole series, whether it’s in Shimomura’s sparse, nocturnal piano ballads, or her ethereal, dramatic boss themes (which have even made appearances in samples from rappers like J. Cole and Lil Bibby).

Between Kingdom Hearts and her recently-helmed soundtrack for Final Fantasy XV, Shimomura’s work in the 21st century has taken on a more sentimental quality afforded by her newfound access to large orchestras. Compared to her earlier work, which was often defined by its eccentric complexity, Shimomura’s music has now come to be associated with a grandiosity straight out of Hollywood, fueled by big emotions and a regal sense of drama befitting of the huge theaters she now fills. Earlier this year, she released her score for the long-awaited Kingdom Hearts III, and listening to it side-by-side with her iconic ‘90s work reveals not only how much Shimomura has evolved as an artist, but how she’s been able to remain relevant and adapt as video game music has trended more toward the cinematic.

“I don’t think the actual process of creating music has changed one bit,” Shimomura tells me when I ask her how her process has evolved over the years as technology has shifted. “There is a difference between having three sound channels and having an entire orchestra, but the difference manifests itself in the final product itself, rather than what goes behind the music.” Despite the fact that her work has both channeled and impacted countless genres (be it techno, ambient, hip-hop, or otherwise), Shimomura denies taking any influence from these various scenes when writing her music. Instead, she offers that the world around her his where she gets inspiration—whether it’s coming up with the Twilight Town theme song by gazing out her patio at sunset, or getting the melody idea for Street Fighter II’s Blanka by seeing a paper bag on the subway that shared the same green color of the character’s skin. Just by following her own muse, Shimomura has accidentally become one of the most influential figures in the world of video game music; an unwitting witness to her own personal kingdom.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.