The First iPhone Was a Landline

Credit to Author: Yuri Litvinenko| Date: Mon, 19 Aug 2019 19:11:40 +0000

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Phone lines, while not initially designed to transfer binary data, turned out to be a good enough way to do so—at least until the 2000s, that is.

From sending faxes to browsing the internet, people relied on effectively the same copper wires they used with Ma Bell-leased telephones.

While most of the personal tech evolved towards greater connectivity, landline phones mostly got better only at the ergonomics of calling and dialing.

But a few dared to be smarter—decades before smartphones found their way into our pocket.

Let’s talk about the evolution of the landline smartphone.

“Man-to-man, man-to-machine, machine-to-machine. In a short time, we’ve come a long way.”

– A line from “Challenges of Change,” a 1961 promotional movie from AT&T. Filmed on a height of Space Age anticipation, it shows “Data-Phones”—essentially, modems which could transmit data from punched cards, tapes, or even handwritten notes.

The earliest visions of smartphones didn’t anticipate that we wouldn’t communicate with our our voices

The AT&T video, filled with otherworldly visual effects, is delightful to anyone with an interest in history. At the same time, it shows why landline phones did not become the interactive mediums that smartphones later did.

While the narrator talked about changes in communication, scenarios from the movie showed data exchanges at best, as all meaningful interactions were done by voice and between humans. For example, before loading a punched card, a Data-Phone operator had to chat with the person on the other end of the line. Even in the age of rocket deliveries, shopping over a credit card-enabled videophone would be done by talking to a manager, as if one would in a retail store.

Admittedly, Bell engineers envisioned the future where people would only need to use the keypad to communicate with the source over a phone. A year later, Touch-Tone phones were presented to the U.S. public. While the speed of dialing was what AT&T promoted to customers, the DTMF (Dual-tone multi-frequency, informally known as “touch-tone”) signals generated by buttons allowed for menu navigation still used today.

How the United Kingdom failed to start an online revolution

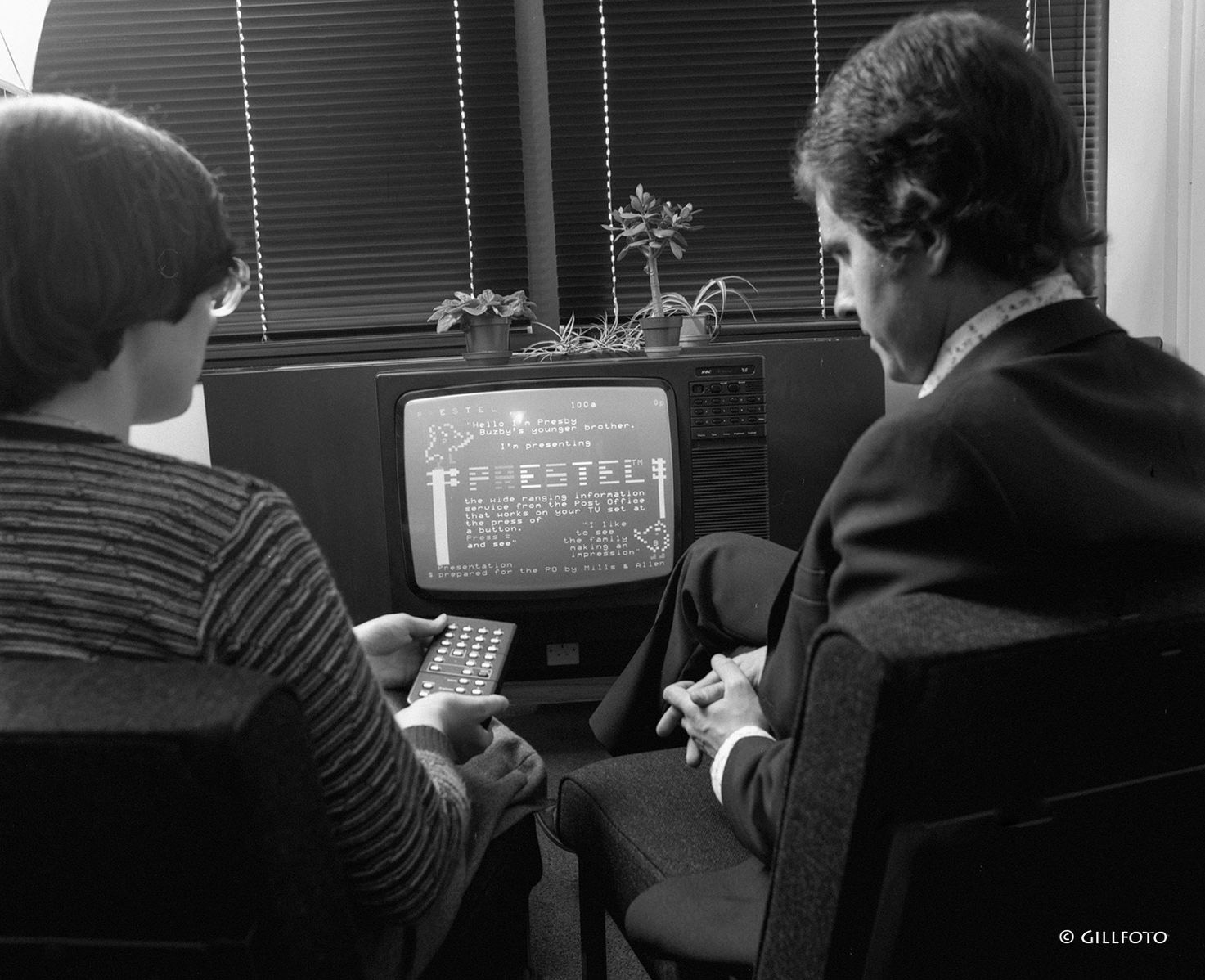

By 1970, additional buttons on each side of a zero competed the 12-button keypad. Twelve buttons were what the UK Post Office had to rely on while developing Prestel, a nationwide service which let people use interactive services on a home video terminal.

Looking back, if there is one thing the UK engineers in the 1970s were fascinated with, it’s putting text on TV screens. In the United States, there wasn’t any notable progress in this field between a TV Typewriter electronic kit and the advent of home computers. The British, on the other hand, went straight towards transferring news, financial data, and TV guides—long before the booming popularity of the Internet, developing two coexisting ways to broadcast text.

One of these technologies, teletext, still lingers to this day across Europe. The text data, complete with color and pseudographics, is being broadcast alongside a TV signal—literally stuffed in between video frames. By design of the aerial transmission, teletext provides no interactivity, leaving the user to flip between different “pages” and occasionally revealing hidden text (the latter was mostly used to hide quiz answers).

Using a phone line instead allowed for higher transfer rate, more personalization (and billing for premium pages) and the ability to run remote software. Over several years since the mass introduction in 1979, Prestel accumulated several online banking, shopping, and booking offerings—even before the home computer boom which pushed operators to add software downloads and games.

Prestel used phone lines and required a phone-like keypad for navigation—surely, it was a fitting technology to build phones of the future around. That didn’t happen on a scale required to ensure Prestel’s success. Instead, the Post Office bet on marrying the network with TV—by offering not even set-top boxes, but Prestel-enabled TVs, priced at £650 at the very least. By contrast, France Télécom leased terminals for their similar Télétel network for free, making Minitel popular enough that it survived until 2012.

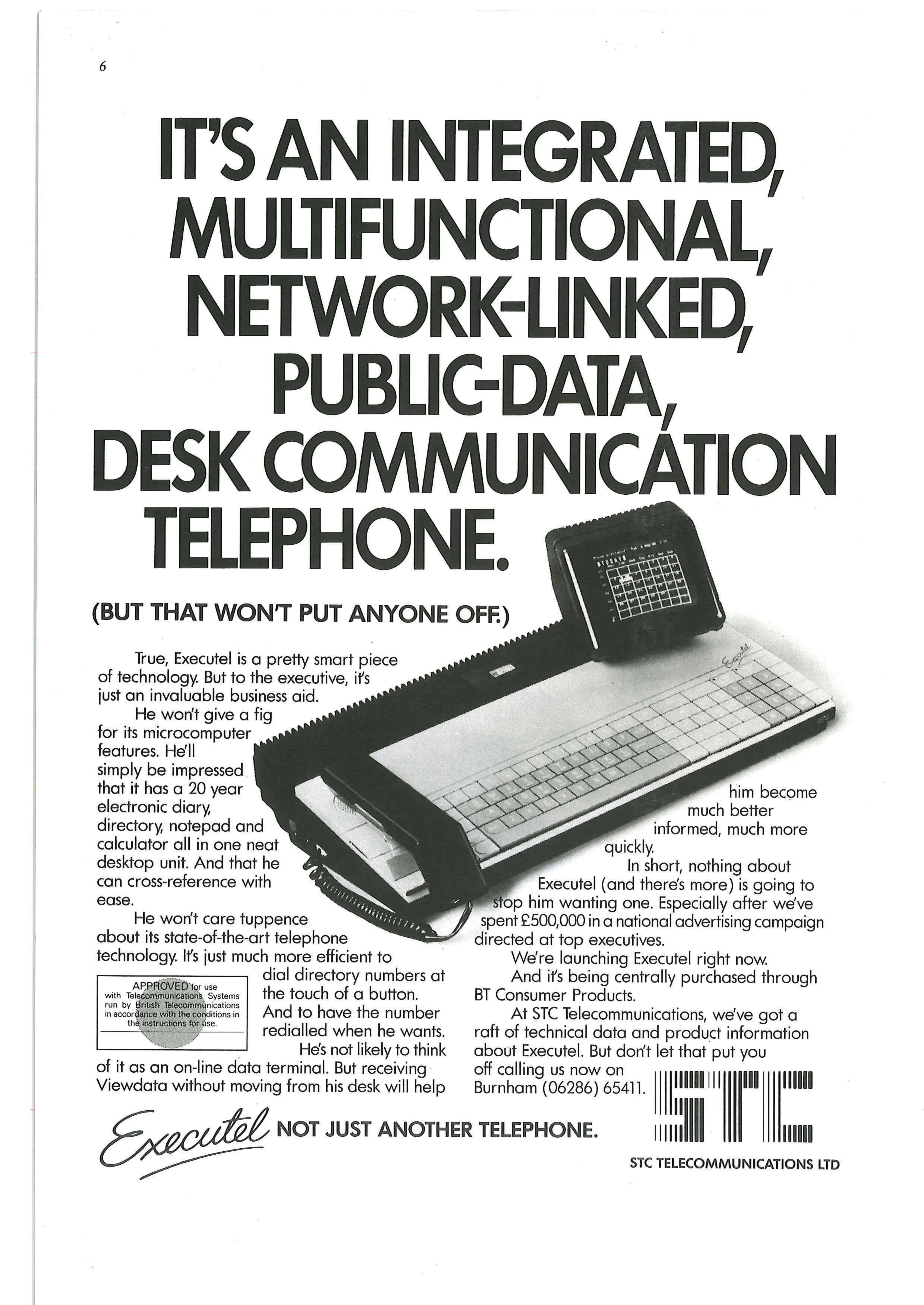

There was just a single Prestel phone—but boy, what a device it was. A wide unit with a small CRT screen and a QWERTY keyboard, STC Executel was an “intelligent display telephone” which combined voice and text communications with almost every productivity feature of its era.

The 1984 ad touted contacts book, calendar, ability to take notes and a “£500,000 in a national advertising campaign directed at top executives.” Being essentially an Intel 8085-based computer, it stored its software on a dictaphone cassette and could connect to a “secretarial unit” which allowed updating the data from another desk.

Just 10,000 Executel devices were sold, according to the designer David Leers. Only five thousand of them were sold, with the rest repurposed.

What might have saved Executel from being completely forgotten is its sleek, modern look.

Several Executels found their way in industrial design museums, although the plastics used for the keyboard turned out to be prone to yellowing. Just last week, one appeared on the YouTube channel Techmoan.

The most advanced landline phone of 1998 was literally called “iPhone”

A British oddity, Executel was simply unknown stateside. Still, the idea of a “computer phone” was a part of the social consciousness, and the manufacturers have toyed with it—if only by exploring. One of the most well-known prototypes was made by Apple by 1984. The “MacPhone” concept had a touchscreen for sending notes and signing checks, but, like other projects by Hartmut Esslinger, was only meant for finding new design elements.

But in the 1990s, the rising popularity of the Internet, a desire for a “post-PC” device and plain old technical progress paved the way for household devices which were meant to connect to the phone line. These so-called “Internet appliances” were promising easy Web and email access in a device which supposed to be as easy-to-use as TVs, music centers … or phones.

But while most IAs were simply low-end computers with a handset on top of it (I’m looking at you, Intel Dot.Station), there was just one which could actually replace a landline phone. And yes, it was actually called the iPhone.

Released in 1997, the original iPhone was made by InfoGear, a startup made from one of the National Semiconductor labs. Despite its big, full-VGA touchscreen and a slide-out keyboard, it looked like a contemporary phone. But on top of making calls, it could work with email and “full” versions of web sites—a feat achieved by off-loading some of the computational power to InfoGear servers.

It isn’t even the name or the web capabilities which made one think of the Apple iPhone, but the way all features were integrated. Just like on modern mobile phones, it was possible to dial a number from a web page by tapping it. The InfoGear’s phone did not only have a voicemail, but could transcribe the incoming messages to text.

While the phone made the international headlines, it was eventually forgotten alongside with the rest of the IA market—especially when InfoGear was bought by Cisco. The story took another turn when Apple released its iPhone—Cisco sued them for trademark infringement. Eventually, the two companies came to an out-of-court settlement.

(It wasn’t the last time Apple and Cisco discussed trademark issues. The iOS name, in fact, belongs to Cisco and is licensed to Apple—and might be the reason the latter doesn’t want people to use the phrase “iOS devices.”)

A British lord asked all users of his “superphone” to harass a journalist

To people focused solely on computing history, Alan Sugar is a businessman whose Amstrad micros and ZX Spectrum models contributed heavily to the UK home computer industry.

But to everyone else, he is a bigoted, homophobic billionaire in power who keeps his domestic relevance by hosting a TV show originally presented in the U.S. by Donald Trump.

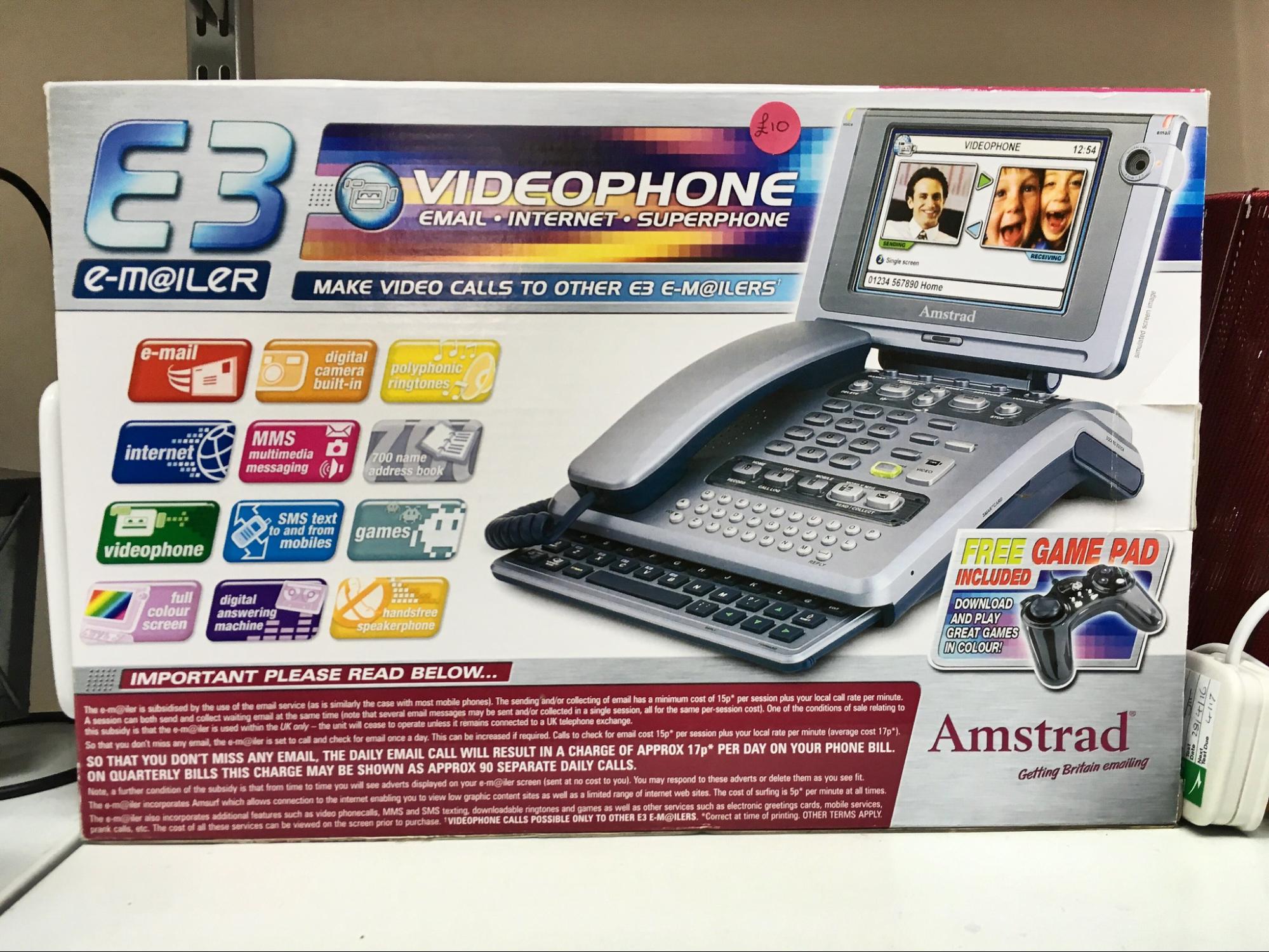

And by the year 2000, his company had lost all that goodwill by releasing products that few people wanted. The PenPad PDA was slow, bulky and had a deteriorating rubber shell; the PcW16 desktop computer had a black-and-white screen and a processor from 1976 despite being released in 1995; the GX4000 game console was just a reason to sell cassette computer games on cartridges for a higher price. Eventually, Amstrad spun off its computing division and focused all its resources on Betacom, a communication company it had acquired. The result was Amstrad E-m@iler, the last attempt to push an Internet-connected landline phone to the mass market.

As a piece of hardware, it wasn’t much different from the InfoGear iPhone. What set it apart was the business model: instead of offering a monthly fee, Amstrad made the E-m@iler operate exclusively through a premium-rate phone number—and put another fee on top. “Sure, if I was organized and could send a day’s worth of emails and SMS messages in one sitting then the prospect of paying 12p for a single session online (plus the cost of the phone call) would be a small price to pay. But I’m not. And I can’t,” noted Tim Richardson of The Register in their 20002 review of a revised E-m@ailer Plus.

Later models of E-m@iler, like the 2004 E3 Superphone, added new features and new ways to get as much profit per user as possible. The ability to play ZX Spectrum games was added, although it was only possible to rent them—again, with paying per call and per service at the same time. The new color screen was used to display ads, with the phone periodically dialing home to download new banners (thankfully, on a toll-free number).

In 2011, the year Amstrad E-m@iler services were shut down, Sugar admitted that “it was slightly too late,” but noted that the subsidized lineup eventually recouped all the costs with services.

He definitely was not as accepting in 2001, though, when he noticed E-m@iler in the list of “techno-flops” in The Independent. The mild criticism (“not proving the success that Sir Alan Sugar had hoped” was all that was ever written about the phone) pushed Sugar to send a message to all 95,000 service subscribers, asking them to send an email to Charles Arthur, the newspaper’s tech editor.

“It occurred to me that I should send an email to Mr. Charles Arthur telling him what a load of twaddle he is talking. If you feel the same as me and really love your e-mailer, why don’t you let him know your feelings by sending him an email,” he wrote in a letter with Mr. Arthur’s address attached.

While the journalist had to cope with more than 1,300 letters—none of which were written by Sugar himself—some of them, eventually published online, exposed hardware faults, annoying bugs, and a helpline being directed to a premium-rate number.

“With this device we can charge advertisers, say, 10p for each customer to receive an ad they will see all day, and charge the advertisers £10 whenever a customer calls them by pressing the ‘services button.’ Or it may be that we give them the ad—free but they pay £25 whenever somebody calls—it’s a no-brainer.”

– Alan Sugar, positioning the E-m@iler as an “electronic billboard” to the readers of Marketing Week. Even considering that Internet phones were not as widespread as PCs, the ballpark cost per click sounds insane. However, as we’ve seen in the past, no one really knew by then how much web advertising should cost.

When asked to reflect on the 1997 iPhone, Robert Ackerman, a venture capitalist who pushed for the independence of InfoGear, said: “We were early into the marketplace. Ten years later, a very different story.” By contrast, Alan Sugar said he was ten years too late—and God knows which decade would be right for the Executel.

The world seemed to be fine with landline phones staying in their lane. But I can’t help but wonder how they would have evolved if the phone industry wasn’t controlled by the Bell System, the Post Office, or other nationwide monopolies. The original telecommunication industry, in my opinion, would have envisioned the connected world differently, based on the phone network paradigms rather than mainframe-terminal ones. Instead, manufacturers had to find faults in a PC-dominated world to make the case for their devices.

Smart landline phones still exist. Some VoIP (voice over internet protocol) and SIP (session initiation protocol) systems for business—arguably the only purchasers of landlines in 2019—are not only using the Web as an infrastructure, but can open web sites and use Android apps. But I think, when it comes to elegance, they pale in comparison to a device I noticed in Moscow Apple Museum.

After licensing the Newton technology from Apple, Siemens made the NotePhone, their own spin on the original MessagePad PDA. When used by itself, it’s functionally indistinguishable from the Apple device. What makes it special is the base with a handset which added phone and fax capabilities. Even back then, mobile computer expansions were nothing new, but this one seems like an integral part of the device while managing to be self-sufficient.

Maybe, instead of being either “smart” or “dumb,” landlines should have been more elegant in their connection to the world of computers.

Yuri Litvinenko is a trade journalist from Russia. When not covering the dairy industry, he spends time being fascinated by legacy technology, both “retro” and gadgets approaching retro status.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.