The 120-Degree Heat Waves of the Future Could Melt Streets and Bend Train Tracks

Credit to Author: John Surico| Date: Tue, 06 Aug 2019 15:21:46 +0000

Someday in the not-too-distant future, the effective temperatures in New York City will hit 120 degrees. If you were in the five boroughs during the three-day mid-July heat wave where it felt like 110 degrees Fahrenheit, according to the National Weather Service, you got a taste of what extreme heat can do to a city. 50,000 people lost power, the New York Triathlon and other events were canceled, and officials advised people to head to “cooling centers” like libraries and senior centers where they could avoid the heat.

But when NYC’s heat index—a measure of how hot it actually feels to humans—hits 120 degrees, the consequences will be even worse. Here are some possible scenarios, as outlined by experts VICE spoke to:

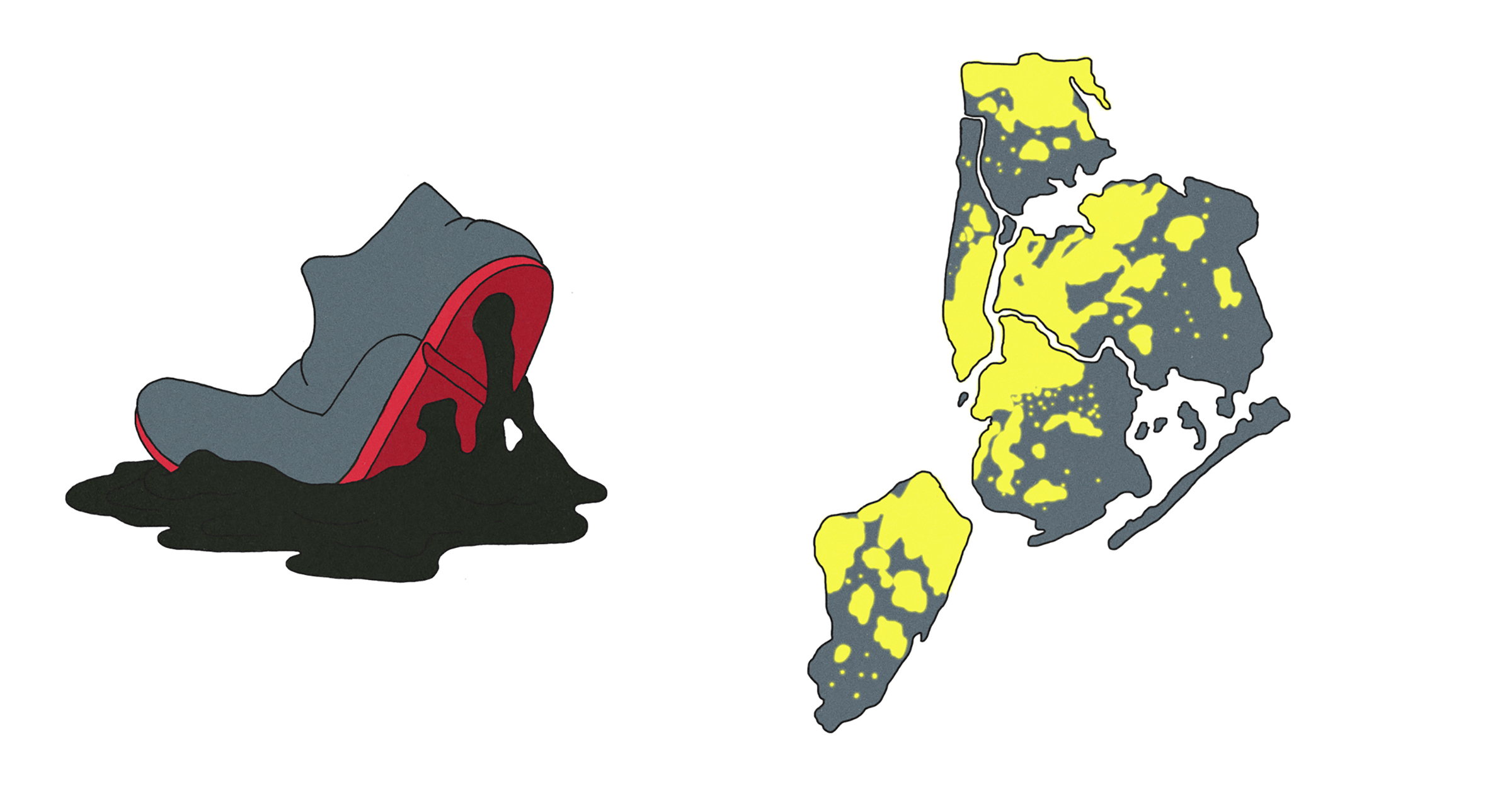

- The asphalt bakes in the sun, causing streets and major roadways to start melting. The resulting black sticky puddles of asphalt threaten to stall cars and burn pedestrians. As a result, vehicular traffic and outdoor walking is temporarily banned.

- The air around the airports at John F. Kennedy and LaGuardia becomes less dense as a result of the heat, and planes can’t reach the greater speeds required to take off in those conditions, especially with their engines not performing at normal levels. All air traffic coming in and out of New York City is halted.

- Railway tracks expand, upending the anchors and ties that keep them in place. The above-ground metal rails of the Long Island Rail Road, New York City subway, and Metro-North begin to buckle like brittle. This “sun kink” stops all service on major commuter rails. Subway station temperatures—always hotter than anything above-ground—become unbearable for humans, and are closed off.

- Massive power outages due to record-high energy use leave millions of consumers stranded without A.C. or lights, as the mercury climbs. High-risk neighborhoods in the South Bronx and southeast Brooklyn are particularly hit hard; cases of heat-related deaths skyrocket, largely impacting older adults, low-income residents who cannot access air conditioners, or those with health problems. Yet New Yorkers are told to stay inside due to the heat emergency.

None of that is particularly far-fetched. A January heat wave in Australia melted a highway, hot air grounded planes in Phoenix in 2017, the sun warping railroad tracks is a well-documented phenomenon, and high temperatures caused at least six deaths in the U.S. during that July heat wave.

“It’s not like we’re projecting what could happen based on science. I mean, these are things that have happened,” said Kurt Shickman, the executive director of Global Cool Cities Alliances, which advises urban centers worldwide on mitigating this phenomenon. “We’re really saying these are things that happen when it gets hot, and not even that hot. And if it all happened at once, it can essentially shut a city down.”

Extreme heat is often called a “silent killer”: Unlike hurricanes, tornadoes, and droughts, it’s hard to visualize a heat wave on TV or in photos. There are no flooded homes or ripped-up buildings. But thanks to climate change “extreme heat events” are likely to become more and more common, putting strain on cities like New York and placing their citizens at risk.

To understand the problem, it’s first worth understanding just why New York City is so hot in the first place. A phenomenon known as the urban heat island effect is the culprit, said Jessica Spaccio, a climatologist at the Northeast Regional Climate Center at Cornell University.

“Urban areas are warmer in the same time period than their rural counterparts,” said Spaccio. “And that’s basically due to the infrastructure of the city, and how they’re built.”

Asphalt and concrete make up 28 percent of New York’s surface area. These surfaces tend to absorb heat, rather than reflect it back into the atmosphere; as a result, the surrounding air stays hotter for longer—which is why nights are often just as sweaty as the daytime during heat waves. “There’s no overnight reprieve,” Spaccio explained. “You can’t just open the window and let cool air in. You have to keep everything shut, and keep the A.C. going constantly.”

Tall buildings impede airflow, and the city is short on green spaces that might cool the air by reflecting heat, consuming hot air to turn into oxygen, transpiring water into the atmosphere, and providing shade. Cue an egg frying on the sidewalk.

By 2050, baseline temperatures in New York are estimated to increase between 4.1 and 5.7 degrees, with double the number of summer days above 90 degrees. Spaccio said that a heat index of 120 would require a temperature of 96, with a relative humidity of 65 to 70. “If we see our baseline temperature warm as the globe is warming, then it’s easier when we have hot days to get above that,” she said.

One important consideration, Shickman said, is that temperatures vary wildly throughout the city. The official measurements are taken in Central Park—a leafy, green area likely to be relatively cool. “When we talk about the average temperature in New York being 120,” Shickman argued, “well, the reality is that it’s 120 in the stations that they take temperatures, but in the South Bronx, I’ll bet it’d be 125, 130.”

One major cause of concern as temperatures rise, Shickman said, is the electrical grid. Shickman’s organization found that in Washington, D.C., when maximum temperatures reached 95 degrees residents were demanding up to 40 percent more power from the grid, due to cranked-up air conditioners. Now imagine even higher temperatures pushing that even further.

“That’s a substantial number, and it’s going to be likely above what the capacity of the grid can deliver for that kind of power,” he said. “So that’s going to be a significant challenge.”

The New York City heat wave in July set a weekend demand record: 12,063 megawatts. (The city normally uses about 11,000 a day.) Con Edison, the city’s primary power supplier, said this usage is what left thousands of customers without power. Worse still, these outages affected a number of low-income communities of color considered to be at high risk for heat deaths.

So what can cities like New York do to survive the sweltering heat? Shickman pointed to a number of short- and long-term strategies, many of which are being deployed worldwide. More roofs could be painted white in order to reflect heat. More green space would also help. Underground areas should be ventilated. And cooling centers should be widely accessible. This summer, Paris—where 500 people died in 2003—launched its new emergency heat plan, which kept public fountains, misting stations, and parks running late or all hours. (By 2050, the city hopes to have its 800 schools turned into cool spaces.)

Beyond that, Shickman said, electrical grids will have to be shifted to renewables like solar or wind, which provide ample shading effects. The urban environment must also take the future into account; in the skyscraper-saturated Tokyo, for example, land development is increasingly factoring in wind paths from Tokyo Bay to help lower temperatures. “Something like that is going to be really important in New York,” Shickman said.

Some of these initiatives are already underway. Jainey Bavishi, the head of the Mayor’s Office of Resilience, is working on the city’s “Cool Neighborhoods” initiative, a $106 million plan to prepare for the extremely hot days to come. “We know that extreme heat is one of the impacts of our changing climate,” said Bavishi. “It actually is one of the deadliest extreme weather events that the city faces; it kills more New Yorkers than any other extreme weather events.”

New York is training home health aides to notice the early signs of heat illness, and launched the “Be a Buddy” program, which taps into community-based organizations in high-risk areas to check in on residents. Bavishi also cited the city’s “Cool Roofs” initiative, which has whited 10 million square feet of rooftop since it launched in 2009 and targeted street tree planting in high-risk neighborhoods. A task force that includes the city’s private and public utilities, she said, meets regularly to discuss future demand trends. (New York State recently passed legislation committing to be 100 percent renewable or carbon-free energy by 2040.)

As we head toward a hotter, more uncertain future, New York and other megacities will have to be both proactive and reactive, to ensure that the nightmare scenarios mentioned above do not happen—or to minimize their impact. Future intense heat waves and other extreme weather events will only serve as reminders that the clock is ticking.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow John Surico on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.