Planting ‘Billions of Trees’ Isn’t Going to Stop Climate Change

Credit to Author: Madeleine Gregory| Date: Mon, 15 Jul 2019 13:14:11 +0000

Planting billions of trees is the most effective way to combat climate change. At least that’s what a recent Science study claimed. Its findings were initially celebrated by a wave of articles, but the response is being met with a flood of criticism—from Indigenous activists, policy experts, and climate scientists.

The study estimated that, currently, an additional 0.9 billion hectares of land are available for reforestation. That’s room for billions of new trees, they said, which would capture 205 gigatons of carbon, or two thirds of what the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates that human carbon emissions have been so far.

Only, reforestation alone is no substitute for radically reducing carbon emissions, as even lead author Jean-Francois Bastin told Motherboard. Just because there’s space for forests doesn’t mean it’s as simple as planting them, and planting billions of trees would be a monumental undertaking with political, environmental, and logistical complications.

The paper itself is a mathematical look at one potential type of solution that doesn’t set out to explore all of these potential complications, so Motherboard spoke to scientists and activists to learn more about how such a massive project might play out.

Is Planting Billions of Trees Even Possible?

Bastin emphasized that his goal was to show Earth’s theoretical potential for reforestation. He said that his research doesn’t translate directly into action, but can be used as a guide for people and places wanting to reforest.

“Until now, we didn’t know what the planet could support physically,” Bastin said. “We were trying to get a view of what could be achieved, what could be supported.”

Though the study didn’t intend to prescribe solutions, many in the media began claiming that massive reforestation efforts would stop climate change. Some climate scientists and policy experts fear that this is an oversimplification of an immensely complicated global issue, and that the optimism around planting trees would crack in the face of serious practical concerns.

For starters, the solution isn’t as easy as putting all the trees back where we found them. Large-scale deforestation has been happening for decades all over the world, and Bastin noted that we need to take into account how ecosystems change over time. As part of the study, his team created an interactive map which can help determine which trees to plant where, ensuring that new forests can survive a changing climate.

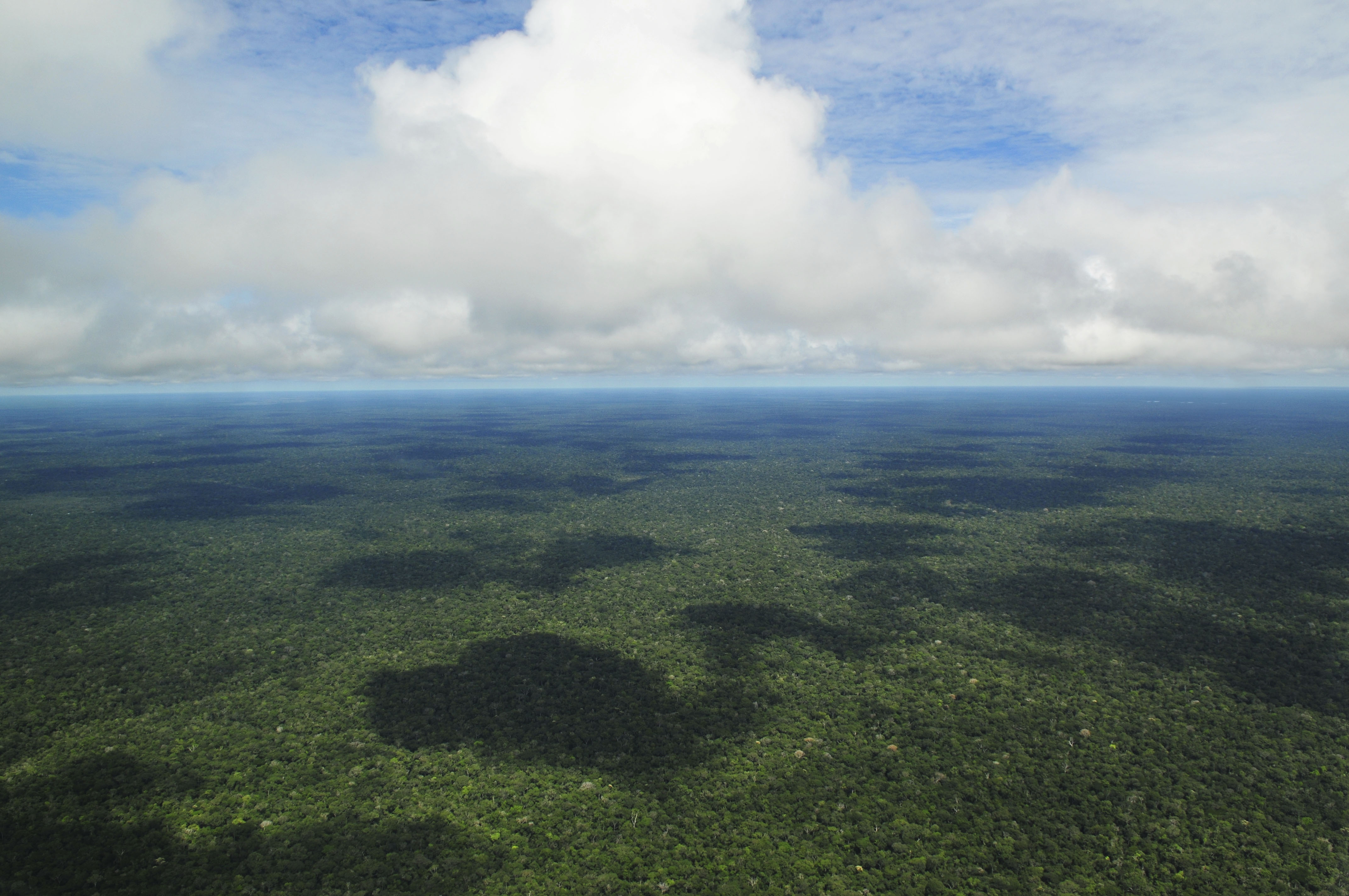

While forests are starting to grow back in some places, including Europe, there’s still large-scale deforestation still taking place in much of the world. These restoration efforts are “basically all for nothing,” Bastin said, if we don’t stop the deforestation in places such as Brazil, where clearcutting of the Amazon is increasing at alarming rates.

A lot of the land identified in this study is privately owned, and convincing people to plant trees in their backyard isn’t always easy. Some governments have instituted policies that pay landowners for reforestation efforts, but those introduce their own problems, including ensuring sustainable forest growth.

Plus, it takes a lot less time to cut a tree down than it does for one to grow to maturity. As soon as a tree is cut down, it releases all that stored carbon back into the atmosphere. Even if we do reforest, the full benefits wouldn’t be realized until the trees reach maturity, which could take decades.

“All the paper itself estimates is the total amount of carbon that could be removed by reforestation. It doesn’t say the speed at which that would happen, the cost, or how you incentivize restoration,” UCLA environmental law professor Jesse Reynolds said. “If we could ignore those, then there are all sorts are effective climate solutions.”

Other scientists fear the findings are too optimistic. In a blog post, scientists Mark Maslin and Simon Lewis question the claim that massive reforestation could really store more than 200 gigatons of carbon, saying it may take hundreds of years to even get close.

Zeke Hausfather, a UC Berkeley climate scientist, noted that these estimates represent a “technical potential rather than economic potential.” He cites a previous study which estimates that, taking into account economic forces, only 30 percent of land that theoretically supports trees can actually be reforested. To complicate matters, he said that sucking carbon out of the atmosphere isn’t as cut and dry as it seems.

“If you emit a ton of carbon, about half stays in the atmosphere. The same math applies to removing a ton of carbon from the atmosphere; only about half is actually permanently removed, as changes in the land and ocean sink balance out the other half,” Hausfather said.

Reforestation Efforts Need Indigenous Voices

The authors of the study say they have begun tailoring their work to local needs, partnering with the United Nations to find governments and organizations that can help to refine their projections. Because so much deforestation has happened on Indigenous lands, reforestation would need to occur there as well. Using this map, people can support local organizations that are working on incorporating other perspectives, including Indigenous land rights and community needs, Bastin said.

The paper makes no direct mention of Indigenous communities who are often exploited by environmental colonialism and excluded from mainstream conservation efforts. And while its authors are trying to reckon with that, its overwhelmingly positive media reception as a climate change fix stoked fears about a plan that omits Indigenous voices.

Such extensive reforestation “would have to be directed by the Indigenous communities in these areas to make it equitable,” BJ McManama, an organizer with the Indigenous Environmental Network, a mostly U.S.-based grassroots alliance of Indigenous environmental justice activists, said.

The act of returning stolen lands and resources is supported by peer-reviewed research as a successful mode of environmental stewardship. A 2017 study published in PNAS found that restoring land rights for Indigenous communities in the Peruvian Amazon “can, at least in the short term, help protect forests,” and has cascading effects that include carbon sequestration and biodiversity protection.

But returning stolen lands is also a vital step in decolonizing a field that in many countries was founded through the racist expulsion of Indigenous communities from their homes. Today a burgeoning environmental movement, largely helmed by Indigenous people, is attempting to rectify these injustices. While activists worry about the Science study’s implications, its virality has nevertheless sparked an important discussion, McManama said.

“While the model points to the amount of land that could be restored with trees, it has no consideration of the very human activity that this will require,” said Alaka Wali, a curator at the Field Museum and founding director of its Center for Cultural Understanding and Change. “Will [Indigenous people] be dispossessed?”

Some biases are so baked into environmentalism that extracting them from policy discussions is seemingly impossible. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations defines “forest” in a way that lumps native trees with alien species. This has allowed for the spread of monoculture plantations in Africa and South America that now harbor acres of eucalyptus and pine farms, and have caused the forcible eviction of Indigenous families.

The cycle of inequality continues as industrialized countries invest in such tree-planting projects as credits to offset their carbon footprint, all the while continuing to rely on fossil fuels.

On a smaller scale, Indigenous communities such as the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin are restoring and managing forests in a way that emphasizes biodiversity and perpetuity. The Menominee have harvested wood from 220,000-acres of forestland for 150 years but have ensured its resilience by planting a variety of tree species and only selectively culling them. “They’re are doing an amazing job [at creating] transferable models for other communities,” said McManama.

*

This may all sound bleak, but it’s not. Nearly everyone agrees that reforestation is an incredibly powerful tool to combat climate change. In addition to carbon capture, it provides much-needed habitat for many organisms, helping slow the current human-caused mass extinction. With the level of carbon already emitted, many—including Bastin—agree that we need to combine both emissions reductions and carbon sequestration in order to effectively slow climate change.

This singular focus on reforestation wasn’t the study’s goal, but many received it that way. Reynolds likens climate mitigation to investing, saying that we need to diversify our solutions in order to reduce risk. If we only rely on reforestation to fight climate change, we’re ignoring the threat of increasing emissions. We’re also ignoring the potential of other solutions like geoengineering.

“If climate change is a risk management problem which calls for many responses, exaggerating the benefits of one or claiming that it is ‘the best climate change solution available today’ poses the real risk of diverting limited attention and resources from other possible responses,” Reynolds said.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.