What Good Does a Pacemaker Do in a Corpse?

Credit to Author: Avir Mitra| Date: Wed, 03 Jul 2019 19:22:11 +0000

Daniel Mascarenhas remembers the exact day he got the idea.

“One of my patients had a pacemaker, and she died,” the Easton, Pennsylvania, cardiologist said, recalling an event in 2002. “I was a little upset. They put in a pacemaker, two days later she was dead, and they buried her with the pacemaker.”

Mascarenhas, 64, is used to his patients being sick, and sometimes dying. But on that day he was troubled by what continued to live on: that peppermint-patty sized device in her chest, which would continue to ping for years to come. That’s a lot of money, he thought, not to mention life-saving technology, buried six feet under.

After seeing this scenario play out over and over, the mild-mannered Indian-American physician came up with a scheme. “I call up the funeral homes. Every week when I have nothing better to do, instead of golfing, I call and find out if they have devices,” he said. If they do, he asks permission from the family to have a mortician remove the device from the body.

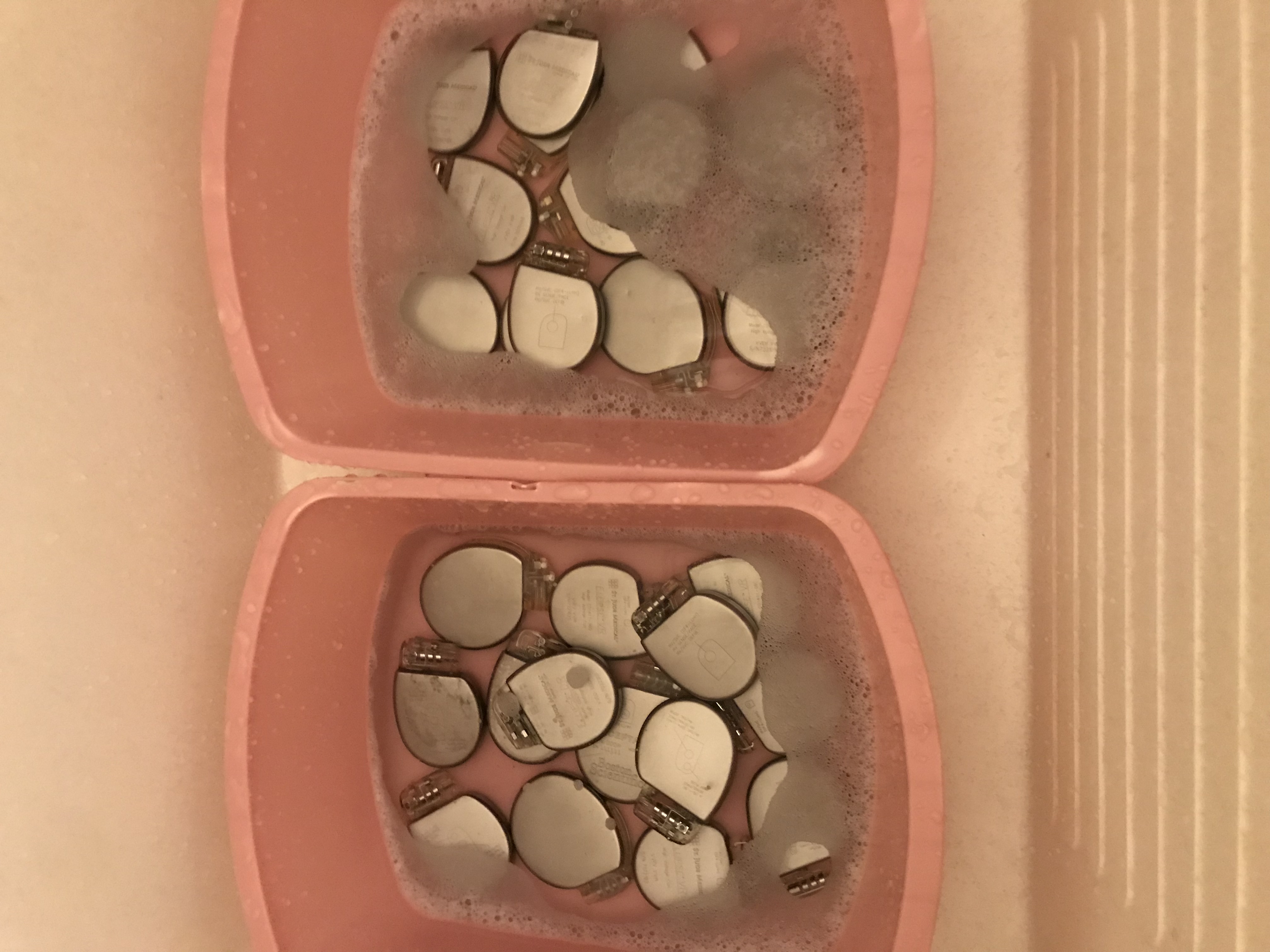

If he gets a pacemaker, Masacarenhas washes off the blood and tissue and sterilizes it in an antimicrobial solution. Then he measures the remaining battery life on the device, in hopes that there will be at least five years left on it that someone can use. “And then once I do that, I put them in a package and send them to India,” he said.

Every year about a quarter of a million people receive pacemakers in the United States. But in India, the number is much smaller, closer to 40,000. That’s less than 0.003 percent of the population. “In India really, there is no safety net,” Mascarenhas said. “So if you don’t have the money, if you’re from the slums, you’re dead.”

Heart-saving devices are expensive. A pacemaker costs $6,000, and a defibrillator averages $28,000—more money than low-income Indians see in a lifetime. And the devices come with about a 10-year battery life. When a patient dies, the device is usually buried with the patient, still fully functional, still ticking away, trying to beat a dead heart in a dead body. “The sad part,” Mascarenhas said, “is that we could reuse them in this country by re-sterilizing them but nobody wants to do this, because we are a land where we learn to waste.”

Putting pacemakers in the mail isn’t an option, Masacarenhas said, because they could get stolen or end up in the hands of customs officers. So Masacarenhas said he usually asks people he knows if they can carry them for him to Mumbai. He advises them on how to package the device so it doesn’t look shady to TSA employees. “If you put them in the middle of the suitcase they can look like a bomb because they’re closed circuit,” he said.

Meanwhile, two doctors in India pick up the pacemakers on the other side—one of them is his former classmate. “Dan was actually my senior in medical school,” said cardiologist Yash Lokhandwala. Lokhandwala said he sees first-hand what happens when patients don’t get pacemakers. “Patients are getting tired, short of breath, dizzy, fainting and then eventually they are dying. I see this a lot.”

“We are a land where we learn to waste.”

Once Lokhandwala receives the devices in India, the pacemakers get sterilized again, this time using ethylene oxide gas. Then his team implants them. “So, if I’ve reused it in a patient who can’t afford it, and who still has five years left to go on that battery, he can start planning for the future. I’ve had it all well thought out,” Mascarenhas said.

As his mission has grown, Mascarenhas’s friends have gotten involved. Ken Metzger, his neighbor and patient, was an avid golfer and loved maintaining his yard. But he struggled with heart failure for 17 years and eventually required an ICD pacemaker. The pacemaker couldn’t fix Metzger’s heart, but it allowed him to enjoy his favorite hobbies—playing golf and coming home to cut the grass. It kept him happy and active.

Metzger died two months ago after a long battle with heart failure. Despite their grief, his family knew what he would have wanted: they donated his pacemaker for the project. “He was excellent,” Sharon Metzger, Ken’s wife, said of Mascarenhas. “We couldn’t have asked for better care.”

There’s just one catch to the Robin Hood-ing: this whole thing isn’t exactly legal. The FDA bans the reuse of pacemakers: they are designated “single use devices.” Even though Mascarenhas follows the sterilization process to the letter, the FDA can’t guarantee sterility once the device has left the packaging, and an implanted device that gets infected can be catastrophic for a patient. Also, there are no federal laws that specify who owns an implanted pacemaker, and therefore who has the right to donate it. In theory, the patient, doctor, manufacturer, and insurer could all lay claim to used medical devices.

The FDA has been on record stating that they would potentially offer a “certificate” of approval to reuse a pacemaker if the safety and effectiveness of the explanted device could be proven. But how one would go about proving that is unclear. For now however, the guideline remains: “Pacemaker reuse is objectionable.”

Emily Larchmont, a nurse, lawyer and an assistant professor of Medical Ethics & Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania, said the FDA’s approach is unnecessarily paternalistic. “These are people who are able to give consent and understand that they are taking on certain risks to receive certain benefits,” she said. In her opinion, manufacturers should be protected from liability when devices are reused, but banning donation is counterproductive.

In India, the laws surrounding this are a little bit looser. It’s still technically illegal, but so far enforcement seems to be low. “We get consent from the patient that there is a small chance of infection,” Mascarenhas said. Not surprisingly, most people opt for the remote possibility of infection over likely death. In addition, recipients need to sign a letter stating that they got their device for free. After all, none of the doctors involved want to be perceived as selling smuggled medical devices.

Regardless, the doctor’s project has steadily grown over the past 15 years. Organizations and advocates such as “My Heart Your Heart” have gained prominence for orchestrating donations to South Africa, the Philippines, Romania and other countries. A study from Mexico showed that infection rates are not significantly higher in patients who receive used devices, as long as proper sterilization protocols are used. And both the donors and recipients are grateful. “It’s nice for us that someone else could use my husband’s device… someone that couldn’t have afforded it,” Sharon Metzger said.

So Mascarenhas must become a pseudo graverobber and smuggler. And while it’s not always easy—Mascarenhas has been detained by customs and all of his luggage was impounded—he said it’s always worth it. “I could find a diamond worth $5,000, but that wouldn’t stimulate me as much as finding a device which has 10 years,” he said. “Because that diamond is not going to give somebody life.”

This article originally appeared on VICE US.